Absence and Invention of the Text in Roberto Bazlen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ten Thomas Bernhard, Italo Calvino, Elena Ferrante, and Claudio Magris: from Postmodernism to Anti-Semitism

Ten Thomas Bernhard, Italo Calvino, Elena Ferrante, and Claudio Magris: From Postmodernism to Anti-Semitism Saskia Elizabeth Ziolkowski La penna è una vanga, scopre fosse, scava e stana scheletri e segreti oppure li copre con palate di parole più pesanti della terra. Affonda nel letame e, a seconda, sistema le spoglie a buio o in piena luce, fra gli applausi generali. The pen is a spade, it exposes graves, digs and reveals skeletons and secrets, or it covers them up with shovelfuls of words heavier than earth. It bores into the dirt and, depending, lays out the remains in darkness or in broad daylight, to general applause. —Claudio Magris, Non luogo a procedere (Blameless) In 1967, Italo Calvino wrote a letter about the “molto interessante e strano” (very interesting and strange) writings of Thomas Bernhard, recommending that the important publishing house Einaudi translate his works (Frost, Verstörung, Amras, and Prosa).1 In 1977, Claudio Magris held one of the !rst international conferences for the Austrian writer in Trieste.2 In 2014, the conference “Il più grande scrittore europeo? Omag- gio a Thomas Bernhard” (The Greatest European Author? Homage to 1 Italo Calvino, Lettere: 1940–1985 (Milan: Mondadori, 2001), 1051. 2 See Luigi Quattrocchi, “Thomas Bernhard in Italia,” Cultura e scuola 26, no. 103 (1987): 48; and Eugenio Bernardi, “Bernhard in Italien,” in Literarisches Kollo- quium Linz 1984: Thomas Bernhard, ed. Alfred Pittertschatscher and Johann Lachinger (Linz: Adalbert Stifter-Institut, 1985), 175–80. Both Quattrocchi and Bernardi -

History and Emotions Is Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena

NARRATING INTENSITY: HISTORY AND EMOTIONS IN ELSA MORANTE, GOLIARDA SAPIENZA AND ELENA FERRANTE by STEFANIA PORCELLI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 STEFANIA PORCELLI All Rights Reserved ii Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante by Stefania Porcell i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Chair of Examining Committee ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Monica Calabritto Hermann Haller Nancy Miller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante By Stefania Porcelli Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi L’amica geniale (My Brilliant Friend) by Elena Ferrante (published in Italy in four volumes between 2011 and 2014 and translated into English between 2012 and 2015) has galvanized critics and readers worldwide to the extent that it is has been adapted for television by RAI and HBO. It has been deemed “ferocious,” “a death-defying linguistic tightrope act,” and a combination of “dark and spiky emotions” in reviews appearing in popular newspapers. Taking the considerable critical investment in the affective dimension of Ferrante’s work as a point of departure, my dissertation examines the representation of emotions in My Brilliant Friend and in two Italian novels written between the 1960s and the 1970s – La Storia (1974, History: A Novel) by Elsa Morante (1912-1985) and L’arte della gioia (The Art of Joy, 1998/2008) by Goliarda Sapienza (1924-1996). -

ERMENEUTICHE DI CESARE GARBOLI Andrea Rondini

rivista di storia della letteratura italiana contemporanea Direttore : Cesare De Michelis Condirettori : Armando Balduino, Saveria Chemotti, Silvio Lanaro, Anco Marzio Mutterle, Giorgio Tinazzi Redazione : Beatrice Bartolomeo * Indirizzare manoscritti, bozze, libri per recensioni e quanto riguarda la Redazione a : « Studi Novecenteschi », Dipartimento di Italianistica, Università di Padova (Palazzo Maldura), Via Beato Pellegrino, 1, 35137 Padova. * « Studi Novecenteschi » è redatto nel Dipartimento di Italianistica, Università di Padova. Registrato al Tribunale di Padova il 17 luglio 1972, n. 441. Direttore responsabile : Cesare De Michelis. * Per la migliore riuscita delle pubblicazioni, si invitano gli autori ad attenersi, nel predisporre i materiali da consegnare alla Redazione ed alla casa editrice, alle norme specificate nel volume Fabrizio Serra, Regole redazionali, editoriali & tipografiche, Pisa · Roma, Serra, 20092 (Euro 34,00, ordini a : [email protected]). Il capitolo Norme redazionali, estratto dalle Regole, cit., è consultabile Online alla pagina « Pubblicare con noi » di www.libraweb.net. * « Studi Novecenteschi » is a Peer-Reviewed Journal. * Stampato in Italia · Printed in Italy www.libraweb.net issn 0303-4615 issn elettronico 1724-1804 rivista di storia della letteratura italiana contemporanea Fabrizio Serra editore Pisa · Roma xxxvi, numero 78, luglio · dicembre 2009 Indirizzare abbonamenti, inserzioni, versamenti e quanto riguarda ® l’amministrazione a : Fabrizio Serra editore , Casella postale n. 1, Succursale n. 8, i 56123 Pisa. * Uffici di Pisa : Via Santa Bibbiana 28, i 56127 Pisa, tel. 050/542332, fax 050/574888, [email protected] Uffici di Roma : Via Carlo Emanuele I 48, i 00185 Roma, tel. 06/70493456, fax 06/70476605, [email protected] * I prezzi ufficiali di abbonamento cartaceo e/o Online sono consultabili presso il sito Internet della casa editrice www.libraweb.net Print and/or Online official subscription prices are available at Publisher’s web-site www.libraweb.net. -

Roberto Calasso - Deconstructing Mythology

Lara Fiorani University College London Roberto Calasso - Deconstructing mythology A reading of Le nozze di Cadmo e Armonia I, Lara Fiorani, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ---------------------------- Lara Fiorani 2 ABSTRACT This thesis reviews Roberto Calasso’s Le nozze di Cadmo e Armonia (1988) and demonstrates that thematic and formal elements of this text allow us to to cast a post- modern and poststructuralist light on his theorization of ‘absolute literature’ – a declaration of faith in the power of literature which may appear to clash with the late twentieth century postmodern and poststructuralist climate responsible for concepts such as la mort de l’auteur. The importance of these findings lies in their going against Calasso’s claim that he never needed to use the word ‘postmodern’ and his complete silence on contemporary literary criticism, as well as on most contemporary authors. Calasso’s self-representation (interviews, criticism and the themes of the part-fictional work-in-progress) acknowledges as influences ancient Greek authors, both canonical and marginal; French décadence; the finis Austriae; Marxism; Nietzsche; Hindu mythology and Aby Warburg. These influences are certainly at work in Le nozze, however they may be employed to subvert Calasso’s self-presentation. I have explored in detail the representations of literature emerging from Le nozze, and shown that they allow the identification in Calasso’s texts of elements confirming his fascination with poststructuralism, in particular with the thought of Jacques Derrida, despite the complete silence on this philosopher throughout Calasso’s work. -

CURRICULUM Anna Dolfi È Nata a Firenze Il 14 Marzo 1948, Dove Si È

Anna Dolfi – Curriculum vitae et studiorum 2019 CURRICULUM Anna Dolfi è nata a Firenze il 14 marzo 1948, dove si è laureata all’Università degli Studi di Firenze nel 1970 discutendo (con 110 e lode) con il prof. Claudio Varese una tesi in Lingua e Letteratura Italiana. Ha iniziato, a partire dall’a.a. 1970-’71, il lavoro presso l'Istituto d'Italiano, poi Dipartimento d'Italianistica dell'Università di Firenze, dove ha svolto fino al 1986 attività di didattica e ricerca (in qualità di addetta alle esercitazioni, borsista, contrattista, ricercatore). Nell'86 ha vinto il concorso a posti di professore universitario di ruolo di prima fascia e dall’agosto 1987 ha assunto (come straordinario; da ordinario dal 1990) la cattedra di Letteratura Italiana Moderna e Contemporanea presso la Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia dell'Università di Trento. Dal 1 novembre 1992 al 31 ottobre 2018 ha ricoperto come ordinario la cattedra di Letteratura Italiana Moderna e Contemporanea presso l'Università degli Studi di Firenze (fino all’ottobre 1995 alla Facoltà di Magistero; dal 1 novembre 1995 alla Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia; dal 2013 alla Scuola di Studi Umanistici e della Formazione), inquadrata nel settore concorsuale: 10/F2 - Letteratura italiana contemporanea (ssd. - L-FIL-LET/11). Dal 1 novembre 1996 al 2015 è stata componente del Collegio dei docenti del Dottorato in Italianistica (poi dottorato in Letteratura e Filologia italiana/indirizzo di Italianistica) dell’Università degli Studi di Firenze; dall’a.a. 2015-2016 del dottorato regionale Pegaso in Studi italianistici coordinato dall’Università di Pisa. Dal 1 novembre 1996 al 31 ottobre 1998 è stata Presidente del Corso di Laurea a esaurimento in Materie Letterarie; dal 1 novembre 1998 al 31 ottobre 2004 Direttore del Dipartimento di Italianistica. -

Fondo De Robertis

Archivio Contemporaneo “Alessandro Bonsanti” Gabinetto G.P. Vieusseux Fondo Giuseppe De Robertis inventario dei manoscritti a cura di Maria Cristina Chiesi Firenze, 2000 Fondo Giuseppe De Robertis. Inventario dei manoscritti Tra le sue carte Giuseppe De Robertis ha conservato un considerevole numero di Manoscritti, oltre a quelli in taluni casi allegati alle lettere ricevute e archiviate insieme con quelle: i suoi, non tutti comunque numerosissimi, e alcuni di altri autori. Essi costituiscono due serie nel Fondo, contraddistinte rispettivamente dai numeri 2 e 3, che fanno seguito alla serie 1 che individua la Corrispondenza. Esiste poi una quarta serie che raccoglie i ri- tagli di giornale. I manoscritti di De Robertis si riferiscono alla sua molteplice attività di critico, attento ai classici e parallelamente ai contemporanei, e tramandano saggi raccolti in volume, articoli pubblicati in pe- riodici, appunti preparatori degli uni e degli altri, lezioni universitarie, conferenze. Sono stati rior- dinati e catalogati attuando una suddivisione per autore trattato, ognuno dei quali viene a costituire un fascicolo contraddistinto da un numero, che nella segnatura occupa il secondo posto (es. D. R. 2. 16 indica il fascicolo Bilenchi). Nel primo fascicolo sono stati collocati gli scritti di argomento miscellaneo, che nella segnatura recano il numero 1, poi di seguito tutti gli altri in ordine alfabeti- co secondo il nome dell'autore su cui verte lo scritto. Infine i non identificati. All'interno di ogni argomento, nel rispetto della sequenza cronologica, a ciascuna unità archivistica catalogata analiti- camente, ossia a ogni scritto, è stato assegnato un numero collocato nella segnatura in terza posi- zione (es. -

Chapter Four

Chapter Four Morante and Kafka The Gothic Walking Dead and Talking Animals Saskia Ziolkowski Although the conjunction of Elsa Morante and Franz Kafka may initially seem surprising, Morante asserts that Kafka was the only author to influence Iler (Lo scialle 215). Morante 's own claim notwithstanding, relatively few ·:tudies compare in detail the author of La Storia (History) and that of Der !'rocess (The Trial). 1 In contrast to Morante, who openly appreciates Kafka but is infrequently examined with him, Dino Buzzati is often associated with Kalka, despite Buzzati's protests. Referring to Kafka as the "cross" he had to ll ·ar (54), Buzzati lamented that critics called everything he wrote Kafka \' ·que. Whereas Buzzati insists that he had not even read Kafka before writ- 111 ' fl deserto dei Tartari (The Tartar Steppe, 1940), which was labeled a 111 ·re imitation of Kafka's work.,2 Morante mentions Kafka repeatedly, par- 1 cularly in the 1930s. Clarifying that Morante later turned from Kafka to 't ·ndhal and other writers, Moravia also remarked upon Kafka's signifi •11111.:c to Morante in this period, referring to the author as Morante's "master" 111d "religion."3 While Morante may be less obviously Kafkan than Buzzati, 11 111.: xploration of her work and her "master's" sheds new light on Morante. I ,ike Marcel Proust, whose importance to Morante has been shown by it ·li1nia Lucamante, Kafka offers Morante an important reference point, es p •iully in the years in which she was establishing herself as an author. l1owing the productive affinities between Morante and Kafka, a German li1 11111:1gc author from Prague, complements studies on Morante and French 111t h11rs. -

La Literatura, Reino Del Mito: Roberto Calasso

36 | 37 La literatura, reino del mito: Roberto Calasso, nacido en Florencia en 1941, dedica Roberto CalaSSO gran parte de su actividad al mundo editorial, siendo considerado el alma mater de la muy prestigiosa Pedro Luis Ladrón de Guevara Mellado Adelphi Edizioni, editorial que tiene en su catálogo a autores como Elias Canetti, Antonin Artaud, Karl Kraus, Wassily Kandinsky, Joseph Roth, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, W.C. Williams, Alberto Savinio, J.R.R. Tolkien, Czeslaw Milosz, Djuna Barnes, James Stephens o Mario de Andrade entre otros. Enorme saber cultural, y heterogéneo, que muestra la pasión de este escritor por la escritura y por los grandes mitos de la literatura, presentes también en su obra literaria. Ejemplo de su amplio abanico de intereses es la edición que hace unos meses, en septiembre de 2003, hizo de una recopilación de sus comentarios a obras por él publicadas bajo el título Cento lettere a uno sconosciuto (Cien cartas a un desconocido) (Adelphi): el desconoci• do no es otro que el lector que se deja aconsejar para sus lecturas por el editor-lector. En los Cursos del Escorial organizados por la Universidad Complutense en 1993 Calasso confesaba que "detrás de mis libros está la cosa más simple de todas: la Mitología: contar historias ya contadas". Sólo con esa premisa podremos comprender el recorrido narrativo del autor. Frente a una literatura del siglo XX empeñada en hacer de la originalidad temática su prin• cipal característica, el autor busca en el mito de cual• quier cultura (hinduista, grecolatina, europea...) el filón para su propia obra narrativa, ya que no es su objetivo la originalidad sino la reinterpretación -en un rasgo más de la globalización que abarca a todos los sectores- de una cultura que se expande por todo el planeta, independiente del lugar de origen. -

CATALOGO 2017 Letteratura Italiana Del ’900 Libreria Malavasi S.A.S

CATALOGO 2017 LETTERATURA ITALIANA DEL ’900 Libreria Malavasi s.a.s. di Maurizio Malavasi & C. Fondata nel 1940 Largo Schuster, 1 20122 Milano tel. 02.80.46.07 fax 02.36.741.891 e-mail: [email protected] http: //www.maremagnum.com http: //www.libreriamalavasi.com Partita I.V.A. 00267740157 C.C.I.A.A. 937056 Conto corrente postale 60310208 Orario della libreria: 10-13,30 – 15-19 (chiuso il lunedì mattina) SI ACQUISTANO SINGOLI LIBRI E INTERE BIBLIOTECHE Negozio storico riconosciuto dalla Regione Lombardia Il formato dei volumi è dato secondo il sistema moderno: fino a cm. 10 ............ = In - 32 fino a cm. 28 ............. = In - 8 fino a cm. 15 ............ = In - 24 fino a cm. 38 ............. = In - 4 fino a cm. 20 ............ = In - 16 oltre cm. 38 .............. = In folio 89580 AMENDOLA Giorgio, Un’isola Milano, Rizzoli, 1980. In-8, brossura, pp. 251. Prima edizione. In buono stato (good copy). 9,50 € 79355 ANDREOLI Vittorino, Il matto inventato Milano, Rizzoli, 1992. In-8, cartonato editoriale, sovracoperta, pp. 232. Pri- ma edizione. In buono stato (good copy). 9,90 € 51595 ANGIOLETTI Giovanni Battista, Scrittori d’Europa Critiche e polemiche Milano, Libreria d’Italia, 1928. In-16 gr., mz. tela mod. con ang., fregi e tit. oro al dorso, conserv. brossura orig., pp. 185,(7). Pri- ma edizione. Ben conservato, con dedica autografa dell’Autore ad Anselmo Bucci. 40 € 47217 ANTOLOGIA CECCARDIANA Introduzione e scelta di Tito Rosina Genova, Emiliano degli Orfini, 1937. In-8 p., brossura (mancanze al dorso, piatto posterio- re staccato), pp. 171,(3), Prima edizione. Antologia dedicata al poeta Ceccardo Roccatagliata Ceccardi, con un suo ritratto. -

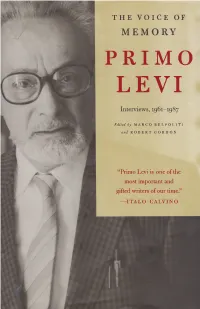

Primo-Levi-The-Voice-Of-Memory

THE VOICE OF MEMORY PRIMO LEVI Interviews, 1961-1987 Edited by M A R C 0 B E L P 0 L I T I and R 0 B E R T G 0 R D 0 N "Primo Levi is one of the most important and gifted writers of our time." -ITALO CALVINO The Voice of Memory The Voice of Memory Interviews 1961-1987 Primo Levi Edited by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon Translated by Robert Gordon The New Press New York This collection © 2001 by Polity Press First published in Italy as Primo Levi: Conversazioni e interviste 1963-87, edited by Marco Belpoliti © 1997 Guilio Einaudi, 1997, with the exception of the interviews beginning on pages 3, 13, 23, and 34 (for further details see Acknowledgments page). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. First published in the United Kingdom by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2001 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2001 Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York ISBN 1-56584-645-1 (he.) CIP data available. The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450West 41st Street, 6th floor, NewYork, NY 10036 www.thenewpress.com Set in Plantin Printed in the -

Versione 36 Pagine

SERGIO SOLMI TRA LETTERATURA E BANCA UNA VITA FRA LETTERATURA E BANCA La vicenda biografica di Sergio Solmi appartiene al novero - invero assai esi - guo - di quelle esistenze che sono contraddistinte da una marcata vocazio - ne e da un indiscutibile, caparbio talento individuale, preservato e anzi svi - luppato attraverso le asperità della vita. Come per tutti coloro che si sono sforzati di congiungere l’attività pratica con quella intellettuale, occorre un particolare sforzo di comprensione per riportare ad unità la personalità com - pleta del biografato, senza cadere negli stereotipi delle facili categorizzazio - ni. È necessario, in concreto, ripercorrere i moventi delle scelte di vita, le calde amicizie, gli scritti così vari eppure intimamente interconnessi, e affi - darsi anche alle testimonianze scaturite dai collaboratori su entrambi i ver - santi. Quando si spengono i riflettori della cronaca, il tempo è galantuomo nei confronti di queste personalità vissute fuori dagli schemi. Solmi era ricordato con ammirazione, simpatia e unanime rimpianto nella tradizione orale del Servizio Legale della Banca Commerciale Italiana, tanto da indurre l’Archivio storico a promuovere tempestivamente la salvaguar - dia e l’inventariazione ragionata di ingenti masse di pratiche giacenti in vari depositi, per far emergere la sua impronta negli aspetti sia ordinari che eccezionali del lavoro di banca, come è ricostruito in questa Monografia e più ampiamente ricercabile nella banca dati dell’Archivio storico di Intesa Sanpaolo. Ma contemporaneamente, con il progredire dell’ Opera omnia edita da Adelphi a partire dal 1983, si andava configurando in modo chiaro la sua statura di grande letterato e ascoltato recensore e saggista, punto di rife - rimento importante nei processi stessi di produzione culturale (dalla poe - sia alla prosa filosofico-morale, con apertura al genere fantascientifico, alla critica letteraria e artistica, alle traduzioni). -

04 Recensioni 4-04 21/04/12 23.31 Pagina 406

04 Recensioni 3-09_04 Recensioni 4-04 21/04/12 23.31 Pagina 406 406 recensioni e segnalazioni Laura Desideri. Bibliografia di Cesare Garboli (1950-2005) , nota introduttiva di Carlo Ginzburg. Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2007, XXXV, 217 p. (Strumenti; 7). ISBN 978-88-7642-196-9. €15,00. Habent sua fata libelli : come i romanzi, così le bibliografie. Cesare Garboli (Viareggio, 17 dicembre 1928 – 10/ 11 aprile 2004) s’addormenta, come il suo Dante, mentre lavorava alla revisione del commento giovanile della Divina Com - media (La Divina Commedia. Le rime, i versi della Vita nuova e le canzoni del Convivio , Tori - no, Einaudi, 1954 [I millenni, 27. Parnaso italiano, II]): era giunto al canto XIX del Pur - gatorio «ne l’ora che non può ‘l calor dïurno | intepidar più ‘l freddo de la luna | vinto da terra, e talor da Saturno» (vv. 1-3). Inattuale fino alla fine in quanto capace di scegliersi autonomamente le proprie strade culturali, politiche ed ideologiche sapendo bene che la forza di una parola critica non risiede solo nell’autorevolezza e nella verità dell’enun - ciato ma soprattutto nei rischi che l’enunciatore corre nell’esporsi (vedi Il coraggio di esse - re inattuali , «La repubblica», 26 giugno 2002, discussione con Roberto Calasso). Inattua - le anche nelle sue enunciazioni di metodo (e quindi nella lotta contro l’insulsa vuotaggine dei pensieri e della scrittura e contro l’ikeaizzazione dell’università): nascono così prese di posizione che lo conducono ad affermare che Sono quel che annoto («Panorama», 2 luglio 1989), Critico sono, ma detesto i libri («Corriere della sera», 6 marzo 1989), Lotto con i libri corpo a corpo («Millelibri», IV, 26 gennaio 1990), Siate postumi! («Panorama», 3 1 maggio 1992, a proposito del Journal di Matilde Manzoni), Troppi pettegolezzi ma è meglio così («La repubblica», 5 novembre 1995 [sulla funzione della critica e sulle sue degenerazioni]).