Chapter Four

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Literary Tradition in Roth's Kepesh Trilogy

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 16 (2014) Issue 2 Article 8 European Literary Tradition in Roth's Kepesh Trilogy Gustavo Sánchez-Canales Autónoma University Madrid Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Sánchez-Canales, Gustavo. -

The Atheist's Bible: Diderot's 'Éléments De Physiologie'

The Atheist’s Bible Diderot’s Éléments de physiologie Caroline Warman In off ering the fi rst book-length study of the ‘Éléments de physiologie’, Warman raises the stakes high: she wants to show that, far from being a long-unknown draf , it is a powerful philosophical work whose hidden presence was visible in certain circles from the Revolut on on. And it works! Warman’s study is original and st mulat ng, a historical invest gat on that is both rigorous and fascinat ng. —François Pépin, École normale supérieure, Lyon This is high-quality intellectual and literary history, the erudit on and close argument suff used by a wit and humour Diderot himself would surely have appreciated. —Michael Moriarty, University of Cambridge In ‘The Atheist’s Bible’, Caroline Warman applies def , tenacious and of en wit y textual detect ve work to the case, as she explores the shadowy passage and infl uence of Diderot’s materialist writ ngs in manuscript samizdat-like form from the Revolut onary era through to the Restorat on. —Colin Jones, Queen Mary University of London ‘Love is harder to explain than hunger, for a piece of fruit does not feel the desire to be eaten’: Denis Diderot’s Éléments de physiologie presents a world in fl ux, turning on the rela� onship between man, ma� er and mind. In this late work, Diderot delves playfully into the rela� onship between bodily sensa� on, emo� on and percep� on, and asks his readers what it means to be human in the absence of a soul. -

Valerie Mcguire, Phd Candidate Italian Studies Department, New York University La Pietra, Florence; Spring, 2012

Valerie McGuire, PhD Candidate Italian Studies Department, New York University La Pietra, Florence; Spring, 2012 The Mediterranean in Theory and Practice The Mediterranean as a category has increasingly gained rhetorical currency in social and cultural discourses. It is used to indicate not only a geographic area but also a set of traditional and even sacrosanct human values, while encapsulating fantasies of both environmental utopia and dystopia. While the Mediterranean diet and “way of life” is upheld as an exemplary counterpoint to our modern condition, the region’s woes cast a shadow over Europe and its enlightened, rationalist ideals—and most recently, has even undermined the project of the European Union itself. The Mediterranean is as often positioned as the floodgate through which trickles organized crime, political corruption, illegal immigration, financial crisis, and more generally, the malaise of globalization, as it is imagined as a utopian This course explores different symbolic configurations of the Mediterranean in twentieth- and twenty-first-century Italian culture. Students will first examine different theoretical approaches (geophysical, historical, anthropological), and then turn to specific textual representations of the Mediterranean, literary and cinematic, and in some instances architectural. We will investigate how representations of the Mediterranean have been critical to the shaping of Italian identity as well as the role of the Mediterranean to separate Europe and its Others. Readings include Fernand Braudel, Iain Chambers, Ernesto de Martino, Elsa Morante, Andrea Camillieri, and Amara Lakhous. Final projects require students to isolate a topic within Italian culture and to develop in situ research that examines how the concept of the Mediterranean may be used to codify, or in some instances justify, certain textual or social practices. -

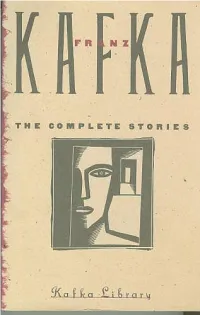

Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka Back Cover: "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. The foreword by John Updike was originally published in The New Yorker. -

PDF-Dokument

1 COPYRIGHT Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Es darf ohne Genehmigung nicht verwertet werden. Insbesondere darf es nicht ganz oder teilweise oder in Auszügen abgeschrieben oder in sonstiger Weise vervielfältigt werden. Für Rundfunkzwecke darf das Manuskript nur mit Genehmigung von Deutschlandradio Kultur benutzt werden. KULTUR UND GESELLSCHAFT Organisationseinheit : 46 Reihe : LITERATUR Kostenträger : P 62 300 Titel der Sendung : Das bittere Leben. Zum 100. Geburtstag der italienischen Schriftstellerin Elsa Morante AutorIn : Maike Albath Redakteurin : Barbara Wahlster Sendetermin : 12.8.2012 Regie : NN Besetzung : Autorin (spricht selbst), Sprecherin (für Patrizia Cavalli und an einer Stelle für Natalia Ginzburg), eine Zitatorin (Zitate und Ginevra Bompiani) und einen Sprecher. Autorin bringt O-Töne und Musiken mit Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Jede Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in den §§ 45 bis 63 Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig © Deutschlandradio Deutschlandradio Kultur Funkhaus Berlin Hans-Rosenthal-Platz 10825 Berlin Telefon (030) 8503-0 2 Das bittere Leben. Zum hundertsten Geburtstag der italienischen Schriftstellerin Elsa Morante Von Maike Albath Deutschlandradio Kultur/Literatur: 12.8.2012 Redaktion: Barbara Wahlster Regie: Musik, Nino Rota, Fellini Rota, „I Vitelloni“, Track 2, ab 1‘24 Regie: O-Ton Collage (auf Musik) O-1, O-Ton Patrizia Cavalli (voice over)/ Sprecherin Sie war schön, wunderschön und sehr elegant. Unglaublich elegant und eitel. Sie besaß eine großartige Garderobe. O-2, O-Ton Ginevra Bompiani (voice over)/ Zitatorin Sie war eine ungewöhnliche Person. Anders als alle anderen. O- 3, Raffaele La Capria (voice over)/ Sprecher An Elsa Morante habe ich herrliche Erinnerungen. -

Il Castellet 'Italiano' La Porta Per La Nuova Letteratura Latinoamericana

Rassegna iberistica ISSN 2037-6588 Vol. 38 – Num. 104 – Dicembre 2015 Il Castellet ‘italiano’ La porta per la nuova letteratura latinoamericana Francesco Luti (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, España) Abstract This paper seeks to recall the ‘Italian route’ of the critic Josep Maria Castellet in the last century, a key figure in Spanish and Catalan literature. The Italian publishing and literary worlds served as a point of reference for Castellet, and also for his closest literary companions (José Agustín Goytisolo and Carlos Barral). All of these individuals formed part of the so-called Barcelona School. Over the course of at least two decades, these men managed to build and maintain a bridge to the main Italian publishing houses, thereby opening up new opportunities for Spanish literature during the Franco era. Thanks to these links, new Spanish names gained visibility even in the catalogues of Italian publishing houses. Looking at the period from the mid- 1950s to the end of the 1960s, the article focuses on the Italian contacts of Castellet as well as his publications in Italy. The study concludes with a comment on his Latin American connections, showing how this literary ‘bridge’ between Barcelona and Italy also contributed to exposing an Italian audience to the Latin American literary boom. Sommario 1. I primi contatti. – 2. Dario Puccini e i nuovi amici scrittori. – 3. La storia italiana dei libri di Castellet. – 4. La nuova letteratura proveniente dall’America latina. Keywords Literary relationships Italy-Spain. 1950’s 1960’s. Literary criticism. Spanish poetry. Alla memoria del Professor Gaetano Chiappini e del ‘Mestre’ Castellet. -

Laughing with Kafka After Promethean Shame

PROBLEMI INTERNATIONAL,Laughing with vol. Kafka 2, no. 2,after 2018 Promethean © Society for Shame Theoretical Psychoanalysis Laughing with Kafka after Promethean Shame Jean-Michel Rabaté We have learned that Kafka’s main works deploy a fully-fledged political critique whose main weapon is derision.1 This use of laughter to satirize totalitarian regimes has been analyzed under the name of the “political grotesque” by Joseph Vogl. Here is what Vogl writes: From the terror of secret scenes of torture to childish officials, from the filth of the bureaucratic order to atavistic rituals of power runs a track of comedy that forever indicates the absence of reason, the element of the arbitrary in the execution of power and rule. How- ever, the element of the grotesque does not unmask and merely denounce. Rather it refers—as Foucault once pointed out—to the inevitability, the inescapability of precisely the grotesque, ridicu- lous, loony, or abject sides of power. Kafka’s “political grotesque” displays an unsystematic arbitrariness, which belongs to the func- tions of the apparatus itself. […] Kafka’s comedy turns against a diagnosis that conceives of the modernization of political power as 1 This essay is a condensed version of the second part of Kafka L.O.L., forthcoming from Quodlibet in 2018. In the first part, I address laughter in Kaf- ka’s works, showing that it takes its roots in the culture of a “comic grotesque” dominant in Expressionist German culture. Günther Anders’s groundbreaking book on Kafka then highlights the political dimensions of the work while criti- cizing Kafka’s Promethean nihilism. -

History and Emotions Is Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena

NARRATING INTENSITY: HISTORY AND EMOTIONS IN ELSA MORANTE, GOLIARDA SAPIENZA AND ELENA FERRANTE by STEFANIA PORCELLI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 STEFANIA PORCELLI All Rights Reserved ii Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante by Stefania Porcell i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Chair of Examining Committee ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Monica Calabritto Hermann Haller Nancy Miller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante By Stefania Porcelli Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi L’amica geniale (My Brilliant Friend) by Elena Ferrante (published in Italy in four volumes between 2011 and 2014 and translated into English between 2012 and 2015) has galvanized critics and readers worldwide to the extent that it is has been adapted for television by RAI and HBO. It has been deemed “ferocious,” “a death-defying linguistic tightrope act,” and a combination of “dark and spiky emotions” in reviews appearing in popular newspapers. Taking the considerable critical investment in the affective dimension of Ferrante’s work as a point of departure, my dissertation examines the representation of emotions in My Brilliant Friend and in two Italian novels written between the 1960s and the 1970s – La Storia (1974, History: A Novel) by Elsa Morante (1912-1985) and L’arte della gioia (The Art of Joy, 1998/2008) by Goliarda Sapienza (1924-1996). -

William Weaver Papers, 1977-1984

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4779q44t No online items Finding Aid for the William Weaver Papers, 1977-1984 Processed by Lilace Hatayama; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé and edited by Josh Fiala. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2005 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the William 2094 1 Weaver Papers, 1977-1984 Descriptive Summary Title: William Weaver Papers Date (inclusive): 1977-1984 Collection number: 2094 Creator: Weaver, William, 1923- Extent: 2 boxes (1 linear ft.) Abstract: William Weaver (b.1923) was a free-lance writer, translator, music critic, associate editor of Collier's magazine, Italian correspondent for the Financial times (London), music and opera critic in Italy for the International herald tribune, and record critic for Panorama. The collection consists of Weaver's translations from Italian to English, including typescript manuscripts, photocopied manuscripts, galley and page proofs. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Advance notice required for access. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections. -

The Castle and the Village: the Many Faces of Limited Access

01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 3 1 The Castle and the Village: The Many Faces of Limited Access jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi Access Denied No author in world literature has done more to give shape to the nightmarish challenges posed to access by modern bureaucracies than Franz Kafka. In his novel The Castle, “K.,” a land surveyor, arrives in a village ruled by a castle on a hill (see Kafka 1998). He is under the impression that he is to report for duty to a castle authority. As a result of a bureaucratic mix-up in communications between the cas- tle officials and the villagers, K. is stuck in the village at the foot of the hill and fails to gain access to the authorities. The villagers, who hold the castle officials in high regard, elaborately justify the rules and procedures to K. The more K. learns about the castle, its officials, and the way they relate to the village and its inhabitants, the less he understands his own position. The Byzantine codes and formalities gov- erning the exchanges between castle and village seem to have only one purpose: to exclude K. from the castle. Not only is there no way for him to reach the castle, but there is also no way for him to leave the village. The villagers tolerate him, but his tireless struggle to clarify his place there only emphasizes his quasi-legal status. Given K.’s belief that he had been summoned for an assignment by the authorities, he remains convinced that he has not only a right but also a duty to go to the cas- tle! How can a bureaucracy operate in direct opposition to its own stated pur- poses? How can a rule-driven institution be so unaccountable? And how can the “obedient subordinates” in the village wield so much power to act in their own self- 3 01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 4 4 jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi interest? But because everyone seems to find the castle bureaucracy flawless, it is K. -

Featuring Martin Kippenberger's the Happy

FONDAZIONE PRADA PRESENTS THE EXHIBITION “K” FEATURING MARTIN KIPPENBERGER’S THE HAPPY END OF FRANZ KAFKA’S ‘AMERIKA’ ACCOMPANIED BY ORSON WELLES’ FILM THE TRIAL AND TANGERINE DREAM’S ALBUM THE CASTLE, IN MILAN FROM 21 FEBRUARY TO 27 JULY 2020 Milan, 31 January 2020 – Fondazione Prada presents the exhibition “K” in its Milan venue from 21 February to 27 July 2020 (press preview on Wednesday 19 February). This project, featuring Martin Kippenberger’s legendary artworkThe Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika” accompanied by Orson Welles’ iconic film The Trial and Tangerine Dream’s late electronic album The Castle, is conceived by Udo Kittelmann as a coexisting trilogy. “K” is inspired by three uncompleted and seminal novels by Franz Kafka (1883-1924) ¾Amerika (America), Der Prozess (The Trial), and Das Schloss (The Castle)¾ posthumously published from 1925 to 1927. The unfinished nature of these books allows multiple and open readings and their adaptation into an exhibition project by visual artist Martin Kippenberger, film director Orson Welles, and electronic music band Tangerine Dream, who explored the novels’ subjects and atmospheres through allusions and interpretations. Visitors will be invited to experience three possible creative encounters with Kafka’s oeuvre through a simultaneous presentation of art, cinema and music works, respectively in the Podium, Cinema and Cisterna.“K” proves Fondazione Prada’s intention to cross the boundaries of contemporary art and embrace a vaste cultural sphere, that also comprises historical perspectives and interests in other languages, such as cinema, music, literature and their possible interconnections and exchanges. As underlined by Udo Kittelmann, “America, The Trial, and The Castle form a ‘trilogy of loneliness,’ according to Kafka’s executor Max Brod. -

Homage to Alberto Moravia: in Conversation with Dacia Maraini At

For immediate release Subject : Homage to Alberto Moravia: in conversation with Dacia Maraini At: the Italian Cultural Institute , 39 Belgrave Square, London SW1X 8NX Date: 26th October 2007 Time: 6.30 pm Entrance fee £5.00, booking essential More information : Press Officer: Stefania Bochicchio direct line 0207 396 4402 Email [email protected] The Italian Cultural Institute in London is proud to host an evening of celebration of the writings of Alberto Moravia with the celebrated Italian writer Dacia Maraini in conversation with Sharon Wood. David Morante will read extracts from Moravia’s works. Alberto Moravia , born Alberto Pincherle , (November 28, 1907 – September 26, 1990) was one of the leading Italian novelists of the twentieth century whose novels explore matters of modern sexuality, social alienation, and existentialism. or his anti-fascist novel Il Conformista ( The Conformist ), the basis for the film The Conformist (1970) by Bernardo Bertolucci; other novels of his translated to the cinema are Il Disprezzo ( A Ghost at Noon or Contempt ) filmed by Jean-Luc Godard as Le Mépris ( Contempt ) (1963), and La Ciociara filmed by Vittorio de Sica as Two Women (1960). In 1960, he published one of his most famous novels, La noia ( The Empty Canvas ), the story of the troubled sexual relationship between a young, rich painter striving to find sense in his life and an easygoing girl, in Rome. It won the Viareggio Prize and was filmed by Damiano Damiani in 1962. An adaptation of the book is the basis of Cedric Kahn's the film L'ennui ("The Ennui") (1998). In 1960, Vittorio De Sica cinematically adapted La ciociara with Sophia Loren; Jean- Luc Godard filmed Il disprezzo ( Contempt ) (1963); and Francesco Maselli filmed Gli indifferenti (1964).