Intimacy and Warmth In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

K O R E a N C in E M a 2 0

KOREAN CINEMA 2006 www.kofic.or.kr/english Korean Cinema 2006 Contents FOREWORD 04 KOREAN FILMS IN 2006 AND 2007 05 Acknowledgements KOREAN FILM COUNCIL 12 PUBLISHER FEATURE FILMS AN Cheong-sook Fiction 22 Chairperson Korean Film Council Documentary 294 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea 130-010 Animation 336 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Daniel D. H. PARK Director of International Promotion SHORT FILMS Fiction 344 EDITORS Documentary 431 JUNG Hyun-chang, YANG You-jeong Animation 436 COLLABORATORS Darcy Paquet, Earl Jackson, KANG Byung-woon FILMS IN PRODUCTION CONTRIBUTING WRITER Fiction 470 LEE Jong-do Film image, stills and part of film information are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, and Film Festivals in Korea including JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), PIFF APPENDIX (Pusan International Film Festival), SIFF (Seoul Independent Film Festival), Women’s Film Festival Statistics 494 in Seoul, Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival, Seoul International Youth Film Festival, Index of 2006 films 502 Asiana International Short Film Festival, and Experimental Film and Video Festival in Seoul. KOFIC appreciates their help and cooperation. Contacts 517 © Korean Film Council 2006 Foreword For the Korean film industry, the year 2006 began with LEE Joon-ik's <King and the Clown> - The Korean Film Council is striving to secure the continuous growth of Korean cinema and to released at the end of 2005 - and expanded with BONG Joon-ho's <The Host> in July. First, <King provide steadfast support to Korean filmmakers. This year, new projects of note include new and the Clown> broke the all-time box office record set by <Taegukgi> in 2004, attracting a record international support programs such as the ‘Filmmakers Development Lab’ and the ‘Business R&D breaking 12 million viewers at the box office over a three month run. -

Mongrel Media Presents

Mongrel Media Presents Pieta A film by Kim Ki-duk (104 min., Korea, 2012) Language: Korean Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1028 Queen Street West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html Ψ PIETA is… ‘Pieta’, meaning ‘pity’ in Italian, is an artistic style of a sculpture or painting that depicts the Virgin Mary sorrowfully cradling the dead body of Jesus. The Virgin Mary’s emotions revealed in ‘Pieta’ have represented the countless pains of loss that humans experience in life that are universally identifiable throughout centuries. It has been revived through master artists such as Michelangelo and Van Gogh. Ψ Main Credit a KIM Ki-duk Film production Executive producers KIM Ki-duk, KIM Woo-taek Producer KIM Soon-mo Written & directed by KIM Ki-duk Cinematography JO Yeong-jik Production design LEE Hyun-joo Editing KIM Ki-duk Lighting CHOO Kyeong-yeob Sound design LEE Seung-yeop (Studio K) Recording JUNG Hyun-soo (SoundSpeed) Music PARK In-young Visual effects LIM Jung-hoon (Digital Studio 2L) Costume JI Ji-yeon Set design JEAN Sung-ho (Mengganony) World sales FINECUT Domestic distributor NEXT ENTERTAINMENT WORLD INC. ©2012 KIM Ki-duk Film. All Rights Reserved. Ψ Tech Info Format HD Aspect Ratio 1.85:1 Running Time 104 min. Color Color Ψ “From great wars to trivial crimes today, I believe all of us living in this age are accomplices and sinners to such. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Cultural Hybridity in the Contemporary Korean Popular Culture Through the Practice of Genre Transformation

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 6-28-2018 2:30 PM Cultural Hybridity in the Contemporary Korean Popular Culture through the Practice of Genre Transformation Kyunghee Kim The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Blackmore, Tim The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Kyunghee Kim 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kim, Kyunghee, "Cultural Hybridity in the Contemporary Korean Popular Culture through the Practice of Genre Transformation" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5472. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5472 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract The focus of this dissertation is to show how the media of contemporary Korean popular culture, specifically films, are transformed into “hybrid cultural forms” through the practice of genre transformation. Since the early 21st century, South Korean popular culture has been increasingly spreading across the globe. Despite its growing attention and popularity, Korean pop culture has been criticized for its explicit copying of Western culture with no unique cultural identity. Others view the success of Korean media, both its creative mimicry and its critique of the West, as a new hybrid form that offers the opportunity for reassertion of local identity as well as challenging the global hegemony of the West. -

The Best of Korean Cinema Returns to London

THE BEST OF KOREAN CINEMA RETURNS TO LONDON 제 9회 런던한국영화제 / OFFICIAL FESTIVAL BROCHURE / 6-21 NOVEMBER 2014 14�OZE�454 .pdf 1 10/10/14 1:53 PM An introduction by Tony Rayns You wouldn’t know it from the pro- It’s a sad fact that not many of these gramming of this year’s other film fes- films will go into distribution in Britain, tivals in London, but 2014 has been a not because they lack audience ap- terrific year for Korean cinema. Two peal but because the ever-rising cost home-grown blockbusters have domi- of bring films into distribution in this nated the domestic market (one of country makes it hard for distributors to them has been seen by nearly half the take chances on unknown quantities. entire population of South Korea!), Twenty years ago the BBC and Chan- C and there have also been outstanding nel 4 would have stepped in to help, M achievements in the art-film sector, the but foreign-language films get less and indie sector, the student sector – and less exposure on our television. Maybe Y in animation and documentary. And just the decline in the market for non-Hol- CM as you begin to salivate over all those lywood films will mark the start of new films you’re afraid you’ll never get to initiatives in on-demand streaming and MY see, along comes the London Korean downloading, but those innovations are CY Film Festival to save the day. still in their infancy. And so the London CMY I’ve said this before, but it bears Korean Film Festival has an absolutely repeating: London is extremely lucky crucial role in bringing new Korean K to have the largest and most ambitious movies to the people who want to see of all the Korean Film Festivals staged them. -

Entre2rives-Dp.Pdf

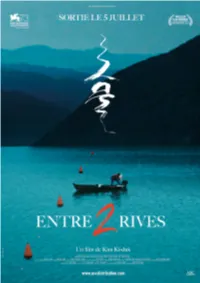

Synopsis Sur les eaux d'un lac marquant la frontière entre les deux Corées, l'hélice du bateau d'un modeste pêcheur nord-coréen se retrouve coincé dans un filet. Il n'a pas d'autre choix que de se laisser dériver vers les eaux sud-coréennes, où la police aux frontières l'arrête pour espionnage. Il va devoir lutter pour retrouver sa famille... “Sans le vouloir, les hommes sont prisonniers de l'idéologie politique des lieux où ils sont nés. À travers le personnage du pêcheur (Chul-woo) qui endure les pires souffrances en allant en Corée du Sud et en retournant en Corée du Nord, nous voyons comment nous sommes sacrifiés par la péninsule coréenne coupée en deux. Et comment cette division génère une grande tristesse...” KIM Ki-duk Les personnages RYOO Seung-bum est Nam Chul-woo KIM Young-min est “l'inquisiteur” “Si un poisson est pris dans le filet, c'est fini” “Ce sont tous des espions potentiels. On ne va pas encore Un modeste pêcheur nord-coréen marié et père d'une petite fille, se faire abuser” Nam Chul-woo, dérive jusqu'en Corée du Sud suite à la panne du Son grand père ayant été tué par les Nord-coréens pendant la guerre moteur de son bateau, dont l'hélice s'est prise dans le filet… Comme de Corée, il nourrit une haine féroce à leur égard. Pour lui tous les sa famille vient avant tout, que ce soit la richesse matérielle, ses Nord-coréens sont des espions en puissance à démasquer, quitte à convictions et la loyauté envers son pays, Chul-woo souffre beaucoup utiliser des méthodes peu orthodoxes. -

The Korean Wave 2007

THE KOREAN THE KOREAN WAVE AS VIEWED THROUGHWAVE THE PAGES OF THE NEW YORK TIMES IN 2007 THE KOREAN WAVE AS As Viewed Through the Pages of The New York Times in 2007 THE KOREAN WAVE AS VIEWED THROUGH THE PAGES OF THE NEW YORK TIMES IN 2007 THE KOREAN WAVE AS This booklet is a collection of 65 articles selected by Korean Cultural Service New York from articles on Korean culture by The New York Times in 2007. THE KOREAN THE KOREAN WAVE AS VIEWED THROUGHWAVE THE PAGES OF THE NEW YORK TIMES IN 2007 THE KOREAN WAVE AS As Viewed Through the Pages of The New York Times in 2007 First edition, March 2008 Edited & published by Korean Cultural Service New York 460 Park Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10022 Tel: 212 759 9550 Fax: 212 688 8640 Website: http://www.koreanculture.org E-mail: [email protected] Copyright©2008 by Korean Cultural Service New York All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recovering, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. From the New York Times © 2007 The New York Times All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of the Material without express written permission is prohibited. Cover & text design by Jisook Byun Printing & binding by Karis Graphic Corp. Printed in New York Korean Cultural Service New York CONTENTS FOREWORD DANCE&THEATER The Korean Wave and American Views of Korea, Yesterday and Today 008 KO–ryO DANCE Theater 081 The Korean Wave: Last Year, Twenty–five Years Ago 012 A Contest for the World, Led by South Koreans 082 With Crews, And Zoos, A B–Boy World 084 MOVIES Jump 087 Tazza 017 FILM 018 FOOD It Came From the River, Hungry for Humans (Burp) 019 Koreans Share Their Secret for Chicken With a Crunch 089 Asian–American Theaters Plan New Festival 021 Heated Competition. -

Cinema As a Window on Contemporary Korea

KOREAN FILM AND POPULAR CULTURE Cinema as a Window on Contemporary Korea By Tom Vick THE FOUNDATIONS OF THE NEW KOREAN CINEMA In 1992, after decades of military rule, South Korea elected its first civilian president, Kim Young-sam. Along with the many social, political, and economic changes that accompa- nied the nation’s shift from military to democratic rule, the Korean film industry under- went a renaissance in both popularity and artistic quality, spurred by public and corporate investment, and created by filmmakers released from decades of strict censor- . when President Kim was informed that the ship that prevented them from directly addressing important issues. According movie Jurassic Park had turned a profit equal to to a frequently repeated anecdote, when President Kim was informed that the the export of 1.5 million Hyundai automobiles, he movie Jurassic Park had turned a profit was inspired to provide greatly increased state Marriage Story. equal to the export of 1.5 million ©1992 Shin Cine Communications Ik Young Films Co., Ltd.. Hyundai automobiles, he was inspired support to the media and culture industries. to provide greatly increased state sup- port to the media and culture indus- tries.1 Prior to that, the surprising box office success of Kim Ui-seok’s Marriage Story in 1992, which was financed in part by the corporate conglomerate Samsung, prompted other corporations to see movies as a worthwhile investment.2 Directors who suffered under censorship took advantage of this new era of free expression and increased funding to take on once forbidden topics. Jang Sun-woo, who had been imprisoned at one point for his political activi- ties, addressed the Kwangju Massacre of May 18, 1980, during which the military brutally suppressed a pro-democratization uprising, in A Petal (1996). -

Dossier De Presse, Fiche Technique Et Visuels HD Sont À Télécharger Sur Notre Site Internet

Un film de KIM KI-DUK Corée du Sud - 2000 - 86 min - Visa N°101332 - VOSTF VERSION RESTAURÉE 2K MEILLEUR FILM FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DU FILM FANTASTIQUE DE BRUXELLES 2001 SYNOPSIS Hee-jin s’occupe des petits îlots de pêche au sein d’un parc naturel. Elle loue les îlots, DISTRIBUTION PRESSE mais s’occupe également de l’hôtel, du transport et de toute la gestion matérielle des MARY-X DISTRIBUTION SF EVENTS clients. Elle survit des loyers, de la nourriture qu’elle vend et de prostitution occasion- 308 rue de Charenton 75012 Paris Tél : 07 60 29 18 10 nelle. N’étant pas intéressée par les autres, elle se fait passer pour muette. Cepen- Tél : 06 84 86 40 70 [email protected] dant, l’arrivée de Hyun-shik, assassin de sa femme et désormais en cavale, l’intrigue. [email protected] L’homme qui essaie à plusieurs reprises de se suicider suscite l’intérêt de la jeune femme. Un étrange couple se forme alors, une relation ambigüe et charnelle. 2 3 En 2004, le Festival de Deauville organise une rétrospective de son travail, l’oc- casion alors pour la critique et le public de découvrir le travail de cet auteur ma- jeur. S’en suit alors une exploitation tardive de ses films. Printemps été automne hiver… et printemps est le premier. Le film, sorti initialement en 2003 en Corée, il remporte le prix du jury Junior au Festival international du film de Locarno la même année et parait l’année suivante en France, où il rencontre un franc succès. -

Il Cinema Di Kim Ki-Duk Tra Rarefazioni Spirituali E Violenza Pittorica

Università degli Studi di Padova Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale Interateneo in Musica e Arti Performative Classe LM-45 Tesi di Laurea Il cinema di Kim Ki-duk tra rarefazioni spirituali e violenza pittorica 1 INDICE: Introduzione metodologica.………………………………….…………………………………………………….4 Introduzione……………………………………………………..………………………………………………………..5 I. Contestualizzazione storica……………………………………………………………………….…………….7 I.1 La divisione di Choson in Corea del Sud e Corea del Nord………...………..……… 7 I.2 Corea del Nord: la dittatura e la censura………………………..……….………..…….. 12 I.3 Corea del Sud dal 1945 agli anni ’90………………………………….……………………….14 II. Biografia di Kim Ki-duk……………………………………………………………………………….……….21 II.1 Dall’infanzia al primo lavoro di regista……………………………………………………..21 II.2 Elementi biografici ritrovabili all’interno dei film……………………………..….……24 II.3 Similitudini con altri registi………………………………………………………………….…….26 III. Il rapporto tra Kim Ki-duk i media, la critica e i festival cinematografici…………..29 III.1 L’arrivo di Kim Ki-duk agli occhi dello spettatore occidentale………….……..29 III.2 La fredda accoglienza in madre patria……………………….…………………………..33 III.3 Rapporto con la critica occidentale………………………………………………………….37 IV. Tratti caratterizzanti i film di Kim Ki-duk…………………………………………………………….45 IV.1 Introduzione agli elementi stilistici e tecnici dei film di Kim Ki-duk……….…45 IV.1.1 La fotografia proveniente dalla pittura……………………………………..46 IV.1.2 Gli oggetti di uso comune e l’assenza di armi……….…….………….…47 IV.1.3 Il personaggio autobiografico……………………………………………….….49 IV.2 Stili artistici e pittorici riconoscibili all’interno dei film…………………….……..50 IV.2.1 La foto e l’immagine rivelatrice di sentimenti………..………………….53 IV.2.2 La gabbia per esseri umani: il corpo……………………………………….….55 IV.2.3 La liberazione dalla gabbia………………………………………………………..59 2 V. -

By KU SANG Translated from the Korean by Brother Anthony, of Taizé

Poems by KU SANG Translated from the Korean by Brother Anthony, of Taizé Contents 1. Mystery ................................................................................................................................. 1 Myself ................................................................................................................................ 1 Meditation .......................................................................................................................... 3 Here and There ................................................................................................................... 4 Within Creation .................................................................................................................. 5 In a Winter Orchard ........................................................................................................... 7 Mystery .............................................................................................................................. 8 Midday Prayer .................................................................................................................... 9 Within an Apple ............................................................................................................... 10 A Pebble ........................................................................................................................... 11 A Bundle of Stray Thoughts ............................................................................................ 12 Concerning -

Download/Constitution of the Republic of Korea.Pdf (Accessed August 12, 2013)

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/42f9j7mr Author Kim, Jisung Catherine Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation By Jisung Catherine Kim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kristen Whissel, Chair Professor Mark Sandberg Professor Elaine Kim Fall 2013 The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation © 2013 by Jisung Catherine Kim Abstract The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation by Jisung Catherine Kim Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Kristen Whissel, Chair In The Intimacy of Distance, I reconceive the historical experience of capitalism’s globalization through the vantage point of South Korean cinema. According to world leaders’ discursive construction of South Korea, South Korea is a site of “progress” that proves the superiority of the free market capitalist system for “developing” the so-called “Third World.” Challenging this contention, my dissertation demonstrates how recent South Korean cinema made between 1998 and the first decade of the twenty-first century rearticulates South Korea as a site of economic disaster, ongoing historical trauma and what I call impassible “transmodernity” (compulsory capitalist restructuring alongside, and in conflict with, deep-seated tradition).