First Published in KINO-KOLO, Ukrainian Film Quarterly, Summer 2001)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

K O R E a N C in E M a 2 0

KOREAN CINEMA 2006 www.kofic.or.kr/english Korean Cinema 2006 Contents FOREWORD 04 KOREAN FILMS IN 2006 AND 2007 05 Acknowledgements KOREAN FILM COUNCIL 12 PUBLISHER FEATURE FILMS AN Cheong-sook Fiction 22 Chairperson Korean Film Council Documentary 294 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea 130-010 Animation 336 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Daniel D. H. PARK Director of International Promotion SHORT FILMS Fiction 344 EDITORS Documentary 431 JUNG Hyun-chang, YANG You-jeong Animation 436 COLLABORATORS Darcy Paquet, Earl Jackson, KANG Byung-woon FILMS IN PRODUCTION CONTRIBUTING WRITER Fiction 470 LEE Jong-do Film image, stills and part of film information are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, and Film Festivals in Korea including JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), PIFF APPENDIX (Pusan International Film Festival), SIFF (Seoul Independent Film Festival), Women’s Film Festival Statistics 494 in Seoul, Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival, Seoul International Youth Film Festival, Index of 2006 films 502 Asiana International Short Film Festival, and Experimental Film and Video Festival in Seoul. KOFIC appreciates their help and cooperation. Contacts 517 © Korean Film Council 2006 Foreword For the Korean film industry, the year 2006 began with LEE Joon-ik's <King and the Clown> - The Korean Film Council is striving to secure the continuous growth of Korean cinema and to released at the end of 2005 - and expanded with BONG Joon-ho's <The Host> in July. First, <King provide steadfast support to Korean filmmakers. This year, new projects of note include new and the Clown> broke the all-time box office record set by <Taegukgi> in 2004, attracting a record international support programs such as the ‘Filmmakers Development Lab’ and the ‘Business R&D breaking 12 million viewers at the box office over a three month run. -

Mongrel Media Presents

Mongrel Media Presents Pieta A film by Kim Ki-duk (104 min., Korea, 2012) Language: Korean Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1028 Queen Street West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html Ψ PIETA is… ‘Pieta’, meaning ‘pity’ in Italian, is an artistic style of a sculpture or painting that depicts the Virgin Mary sorrowfully cradling the dead body of Jesus. The Virgin Mary’s emotions revealed in ‘Pieta’ have represented the countless pains of loss that humans experience in life that are universally identifiable throughout centuries. It has been revived through master artists such as Michelangelo and Van Gogh. Ψ Main Credit a KIM Ki-duk Film production Executive producers KIM Ki-duk, KIM Woo-taek Producer KIM Soon-mo Written & directed by KIM Ki-duk Cinematography JO Yeong-jik Production design LEE Hyun-joo Editing KIM Ki-duk Lighting CHOO Kyeong-yeob Sound design LEE Seung-yeop (Studio K) Recording JUNG Hyun-soo (SoundSpeed) Music PARK In-young Visual effects LIM Jung-hoon (Digital Studio 2L) Costume JI Ji-yeon Set design JEAN Sung-ho (Mengganony) World sales FINECUT Domestic distributor NEXT ENTERTAINMENT WORLD INC. ©2012 KIM Ki-duk Film. All Rights Reserved. Ψ Tech Info Format HD Aspect Ratio 1.85:1 Running Time 104 min. Color Color Ψ “From great wars to trivial crimes today, I believe all of us living in this age are accomplices and sinners to such. -

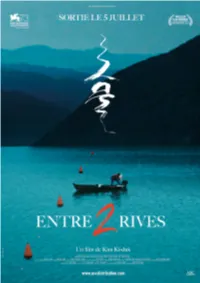

Entre2rives-Dp.Pdf

Synopsis Sur les eaux d'un lac marquant la frontière entre les deux Corées, l'hélice du bateau d'un modeste pêcheur nord-coréen se retrouve coincé dans un filet. Il n'a pas d'autre choix que de se laisser dériver vers les eaux sud-coréennes, où la police aux frontières l'arrête pour espionnage. Il va devoir lutter pour retrouver sa famille... “Sans le vouloir, les hommes sont prisonniers de l'idéologie politique des lieux où ils sont nés. À travers le personnage du pêcheur (Chul-woo) qui endure les pires souffrances en allant en Corée du Sud et en retournant en Corée du Nord, nous voyons comment nous sommes sacrifiés par la péninsule coréenne coupée en deux. Et comment cette division génère une grande tristesse...” KIM Ki-duk Les personnages RYOO Seung-bum est Nam Chul-woo KIM Young-min est “l'inquisiteur” “Si un poisson est pris dans le filet, c'est fini” “Ce sont tous des espions potentiels. On ne va pas encore Un modeste pêcheur nord-coréen marié et père d'une petite fille, se faire abuser” Nam Chul-woo, dérive jusqu'en Corée du Sud suite à la panne du Son grand père ayant été tué par les Nord-coréens pendant la guerre moteur de son bateau, dont l'hélice s'est prise dans le filet… Comme de Corée, il nourrit une haine féroce à leur égard. Pour lui tous les sa famille vient avant tout, que ce soit la richesse matérielle, ses Nord-coréens sont des espions en puissance à démasquer, quitte à convictions et la loyauté envers son pays, Chul-woo souffre beaucoup utiliser des méthodes peu orthodoxes. -

Dossier De Presse, Fiche Technique Et Visuels HD Sont À Télécharger Sur Notre Site Internet

Un film de KIM KI-DUK Corée du Sud - 2000 - 86 min - Visa N°101332 - VOSTF VERSION RESTAURÉE 2K MEILLEUR FILM FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DU FILM FANTASTIQUE DE BRUXELLES 2001 SYNOPSIS Hee-jin s’occupe des petits îlots de pêche au sein d’un parc naturel. Elle loue les îlots, DISTRIBUTION PRESSE mais s’occupe également de l’hôtel, du transport et de toute la gestion matérielle des MARY-X DISTRIBUTION SF EVENTS clients. Elle survit des loyers, de la nourriture qu’elle vend et de prostitution occasion- 308 rue de Charenton 75012 Paris Tél : 07 60 29 18 10 nelle. N’étant pas intéressée par les autres, elle se fait passer pour muette. Cepen- Tél : 06 84 86 40 70 [email protected] dant, l’arrivée de Hyun-shik, assassin de sa femme et désormais en cavale, l’intrigue. [email protected] L’homme qui essaie à plusieurs reprises de se suicider suscite l’intérêt de la jeune femme. Un étrange couple se forme alors, une relation ambigüe et charnelle. 2 3 En 2004, le Festival de Deauville organise une rétrospective de son travail, l’oc- casion alors pour la critique et le public de découvrir le travail de cet auteur ma- jeur. S’en suit alors une exploitation tardive de ses films. Printemps été automne hiver… et printemps est le premier. Le film, sorti initialement en 2003 en Corée, il remporte le prix du jury Junior au Festival international du film de Locarno la même année et parait l’année suivante en France, où il rencontre un franc succès. -

Il Cinema Di Kim Ki-Duk Tra Rarefazioni Spirituali E Violenza Pittorica

Università degli Studi di Padova Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale Interateneo in Musica e Arti Performative Classe LM-45 Tesi di Laurea Il cinema di Kim Ki-duk tra rarefazioni spirituali e violenza pittorica 1 INDICE: Introduzione metodologica.………………………………….…………………………………………………….4 Introduzione……………………………………………………..………………………………………………………..5 I. Contestualizzazione storica……………………………………………………………………….…………….7 I.1 La divisione di Choson in Corea del Sud e Corea del Nord………...………..……… 7 I.2 Corea del Nord: la dittatura e la censura………………………..……….………..…….. 12 I.3 Corea del Sud dal 1945 agli anni ’90………………………………….……………………….14 II. Biografia di Kim Ki-duk……………………………………………………………………………….……….21 II.1 Dall’infanzia al primo lavoro di regista……………………………………………………..21 II.2 Elementi biografici ritrovabili all’interno dei film……………………………..….……24 II.3 Similitudini con altri registi………………………………………………………………….…….26 III. Il rapporto tra Kim Ki-duk i media, la critica e i festival cinematografici…………..29 III.1 L’arrivo di Kim Ki-duk agli occhi dello spettatore occidentale………….……..29 III.2 La fredda accoglienza in madre patria……………………….…………………………..33 III.3 Rapporto con la critica occidentale………………………………………………………….37 IV. Tratti caratterizzanti i film di Kim Ki-duk…………………………………………………………….45 IV.1 Introduzione agli elementi stilistici e tecnici dei film di Kim Ki-duk……….…45 IV.1.1 La fotografia proveniente dalla pittura……………………………………..46 IV.1.2 Gli oggetti di uso comune e l’assenza di armi……….…….………….…47 IV.1.3 Il personaggio autobiografico……………………………………………….….49 IV.2 Stili artistici e pittorici riconoscibili all’interno dei film…………………….……..50 IV.2.1 La foto e l’immagine rivelatrice di sentimenti………..………………….53 IV.2.2 La gabbia per esseri umani: il corpo……………………………………….….55 IV.2.3 La liberazione dalla gabbia………………………………………………………..59 2 V. -

World Sales: FINECUT CO., LTD

World Sales: FINECUT CO., LTD. HEAD OFFICE CANNES CONTACT SALES INTERNATIONAL PUBLICITY 4F Incline Bldg., 891-37, Daechi-dong, Gangnam-gu, Riviera E9/F12 Youngjoo SUH (+33 6 07 25 82 62) Yura KWON ([email protected]) Seoul 135-280, Korea T. +33 4 92 99 33 09 Yunjeong KIM ([email protected]) Oya JEONG ([email protected]) T.+82 2 569 8777 / F.+82 2 569 9466 Luna KIM ([email protected]) E-mail. [email protected] www.finecut.co.kr A Letter From KIM Ki-duk Director’s statement – About ARIRANG An actress almost got in a fatal accident during the filming of Arirang... <Arirang> is If I didn’t give my heart, they would be bad people erased <Dream>. Over the Arirang Hills, send me... about Kim Ki-duk from memories, While filming a scene of committing suicide, the actress was left Arirang... playing 3 roles in 1. but if I gave my heart, I couldn’t let them go till the day that hanging in the air with no one able to do anything. Luckily, we Going up, going down... had left a 50 cm ladder below for just in case. Being sad, being overjoyed... Through <Arirang> I climb over one hill in life. I die as despicable people. If I didn’t quickly jump on that ladder and untie the rope... Being hurt, being happy... Through <Arirang> I understand human beings, thank the Ah… I totally lost it for a while and cried without anyone knowing. Doing this, doing that.. -

KIM KI-DUK DOSYASI: KI-DUK’UN GÖSTERGELER GIZEM ŞIMŞEK DÖNGÜSÜ Kim Ki-Duk Kim

KIM KI-DUK DOSYASI: KI-DUK’UN GÖSTERGELER GIZEM ŞIMŞEK DÖNGÜSÜ Kim Ki-Duk Kim 20 Aralık 1960’da Güney Kore, Bonghwa’da, Kyung- lik anlatımı oldukça yoğun kullanan Ki-duk, Bin-jip (3- sang’ın kuzeyindeki bir taşra köyünde doğan Kim Ki- Iron, 2004) filmiyle diyalogları oldukça azaltır. Moebius duk, 1990-1993 yılları arasında Paris’te Güzel Sanatlar (2013) ile de tamamen diyalogsuz bir film yapmayı ba- eğitimi alır. Ardından Güney Kore’ye geri dönen Ki-duk, şarır. 2014 yapımı Il-dae-il (One on One, 2014) filmini senarist olarak kariyerine devam eder ve 1995 yılında toplum eleştirisini intikam ve adalet üzerinden ele ala- Kore Film Konseyi tarafından düzenlenen senaryo ya- rak, diyaloga çokça başvurarak çeker. Öncesinde, daha rışmasını kazanır. Bunu takip eden 1996 yılında düşük çok toplumu oluşturan bireylere yönelen kamerasını bu bütçeli ilk filmi Ag-o’yu (Crocodile, 1996) çeker. Sinema filmle birlikte topluma çevirmeye başlar. Bu bağlamda eğitimi almamasına, bir yönetmenin yanında asistanlık tümevarımla ilerleyen Ki-duk sineması tümdengelime yapmamasına karşın dünyaya adını duyuran ve sembo- geçiş yapar. 51 na bırakır. Filmlerinde odaklandığı erkek karakterlerin sert olmasının nedenlerini tam olarak açıklamaz- ken, bedensel ihtiyaçlarının gide- rilmesinde hayvanlardan farklı gö- rünmediklerinin de altını çizer. Ki- duk, içgüdülerin toplumsal kural ve tabular olmaksızın giderilmesinin yarattığı ve yaratacağı sorunlara da odaklanır. Bu sorunların ortasında yaşanan, anormal olarak değerlendi- rilebilecek ilişkiler üzerinden sevgi ve aşkı sorgulamayı da ihmal etmez. Ki-duk, Bom yeoreum gaeul gyeoul geurigo bom (Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter and Spring, 2003) filmiy- le birlikte, daha yumuşak görseller Ki-duk’un filmografisini ikiye ayıra- kullandığı, hatta ilişkilere ve aşka kendi tanımıysa “sessizliğin şiiri”dir. -

Intimacy and Warmth In

A C T A K O R ANA VOL. 17, NO. 1, JUNE 2014: 105–135 MIRROR PLAY, OR SUBJECTIVIZATION IN 3 IRON: BASED ON LACAN’S ANALYSIS OF LAS MENINAS AND HIS OPTICAL MODEL By KIM SOH-YOUN Though Kim Ki-duk (Kim Kidŏk) has been most notorious as a filmmaker for his bleak and misogynistic imagination, most notably in The Isle (Sŏm), Address Unknown (Such’wiin pulmyŏng), Bad Guy (Nappŭn namja), The Coast Guard (Haeansŏn), and Samaritan Girl (Samaria), 3 Iron (Pinjip) seems rather a moderate and romantic love story. Nevertheless, the film still remains problematic mainly because of its enigmatic narrative line. The sensational poster image of the female protagonist embracing her husband, while at the same time kissing her lover, epitomizes what is at stake in 3 Iron from a Lacanian perspective. This article is devoted to the task of identifying the logic of subjectivization and different directions of freedom operating in that strange love triangle. What is noticeable in describing the subjectivity of protagonists is 3 Iron’s elaborate use of mise-en-scène through windows and mirrors. The function of reflective materials is to show the protagonists in love as alienated, split and spectral. Being spectral means being related to the status of the Real as otherness or nothingness. In that regard, the personages in Las Meninas could be applied to the characters in this film in terms of their topological status: the royal couple and Min’gyu, Velasquez and T’aesŏk, the princess and Sŏnwha. The first pair has the status of the Other, the second the Real and the third the Symbolic shifting to the Real. -

Korean Post New Wave Film Director Series: Kim Ki-Duk

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2002 Korean post new wave film director series: Kim Ki-Duk Brian M. Yecies University of Wollongong, [email protected] Aegyung Shim Yecies Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Yecies, Brian M. and Yecies, Aegyung Shim, Korean post new wave film director series: Kim Ki-Duk 2002. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/372 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] KIM Ki-Duk Page 1 of 15 Korean Post New Wave Film Director Series: KIM Ki-Duk Translated by Aegyung Shim Yecies and edited byBrian Yecies Uploaded Thursday, 21 November 2002 5500 words The following interview between JUNG Seong-Il, Korean movie critic, and KIM Ki-Duk appeared in the Korean Cine21 magazine issue #339 (Feb. 5-19, 2002). The interview took place in the afternoon on January 30th, 2002. This translated and edited version has been published with permission of Cine21. “Sadistic? I was religious from the start.” -- KIM Ki-Duk JUNG Seong-Il met KIM Ki-Duk who had announced no more interviews. The Prologue Shortly after the release of his new film Bad Guy (Korea 2001), KIM Ki-Duk announced that he was not giving any more interviews. He took a vow of silence, because many of his critics had been criticizing him. -

In Korean Film Industry Who’S Who in Korean Film Industry

Producers and Investors Who’s Who in Korean Film Industry Who’s Who in Korean Film Industry Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheong-sook Who’s Chairperson Korean Film Council 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea 130-010 Editor-in-Chief Daniel D. H. PARK Who Director of International Promotion in Korean Film Industry Editor JUNG Hyun-chang Collaborator YANG You-jeong Researched and Compiled CHOI Tae-young JUNG Eun-jung Contributing Writer SUH Young-kwan Producers and Investors Images : CINE21 ©Korean Film Council 2008 Book Design : Muge Creative Thinking 2 Who’s Who in Korean Film Industry Who’s Who in Korean Film Industry Producers and Investors Note The Who’s Who in Korean Film Industry series will deal with key people and their profiles every year. The first series, Who’s Who in Korean Film Industry : Producers and Investors presents major producers and investors in the Korean film industry. The series will be followed by major actors and directors series in the following years. For further information on the films that are mentioned in this book, please visit KOFIC website (www.kofic.or.kr/english) and see the film database menu. Who’s Who in Korean Film Industry Producers and Investors AHN Soo-hyun 6 CHOI Wan 52 KIM In-soo 96 LEE Eugene 138 SHIM, Jaime 182 CHAE, Jason 12 CHOI Yong-bae 56 KIM, Jonathan 100 LEE Eun 142 SHIN Chul 186 CHIN Hee-moon 18 CHUNG Tae-won 60 KIM Joo-sung 104 LEE Joo-ick 146 SHIN Hye-yeun 190 CHO, David 22 JEONG Seung-hye 64 KIM Kwang-seop 108 LEE Joon-dong 150 SUH Young-joo 194 CHO Kwang-hee -

Fremder Bruder Die Teilungssituation Zwischen Süd- Und Nordkorea Im Spiegel Des Koreanischen Films Seit Dem Korea-Krieg

Fremder Bruder Die Teilungssituation zwischen Süd- und Nordkorea im Spiegel des koreanischen Films seit dem Korea-Krieg Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Akademischen Grades eines Dr. phil., vorgelegt dem Fachbereich 05- Philosophie und Philologie der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz von Kyoung-Suk Sung aus Südkorea Mainz 2013 Referent/in: Korreferent/in: Die mündliche Prüfung am 27.11.2013 Für meinen Mann Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung 1 2. Filmsoziologische Theorie und südkoreanische Konfliktfilme 7 2.1 Die Definition des Konfliktfilms aus filmsoziologischer Sicht 7 2.2 Kracauers Spiegeltheorie 9 2.3 Genrethorie und südkoreanische Filmgenres 13 2.4 Die Entwicklung des Konfliktfilms als Genre 16 2.5 Die Bedeutung des Korea-Krieges und seine kulturelle Auswirkungen 20 2.6 Die Bedeutung der Kriegsfilme zum Konfliktthema 24 2.7 Die Wiederholung des Themas und seine filmsoziologische Wechselwirkung 27 3. Die Nachkriegszeit bis Anfang der 1960er Jahre 34 3.1 Die sozialpolitische Atmosphäre 34 3.2 Bemerkungen im südkoreanischen Film 36 3.3. Filmbeispiele 43 3.3.1 Lebendige Schmerzen des Krieges: PIAGOL und BEAT BACK 43 3.3.2 Nach dem Krieg, und nun?: AIMLESS BULLET 56 3.3.3 Der Zeitgeist der Propagandafilme: FIVE MARINES 63 4. Die frühen 1960er Jahre bis 1980 65 4.1 Die sozialpolitische Atmosphäre 65 4.2 Bemerkungen im südkoreanischen Film 68 4.3. Filmbeispiele 73 4.3.1 Man-Hee Lee und seine Filme in den 1960er Jahren 74 4.3.1.1 Realisierter und realistischer Krieg: THE MARINE NEVER RETURNED 75 4.3.1.2 Familie mit zwei Ideologien: -

Korean Cinema 2 0

KOREAN CINEMA 2007 KOREAN CINEMA 2007 KOREAN CINEMA 2007 Acknowledgements Contents Publisher AN Cheong-sook Chairperson Review of Korean Films in 2007 Korean Film Council 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea (130-010) and the Outlook for 2008 4 Editor-in-Chief Korean Film Council 8 Daniel D. H. PARK Director of International Promotion Feature Films 14 Editors Fiction 16 JUNG Hyun-chang, YANG You-jeong Released 17 Completed & Upcoming 195 Collaborator Documentary 300 Earl Jackson, SON Ju-hee, LEE Yuna, LEE Jeong-min Animation 344 Contributing Writer JUNG Han-seok Short Films 353 Fiction 354 Film image, stills, and part of film information are provided by directors, producers, production & sales Documentary 442 companies, and Film Festivals in Korea including JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), PIFF (Pusan Animation 450 International Film Festival), WFFIS (Women’s Film Festival in Seoul), PIFAN (Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival), AISFF (Asiana International Short Film Festival) and EXiS (Experimental Film and Video Experimental 482 Festival in Seoul). KOFIC appreciates their help and cooperation. Appendix 490 ©Korean Film Council 2007 Statistics 492 lndex of 2007 films 499 Book Design Muge Creative Thinking Addresses 518 Print Dream Art about this film is its material. It is quite unique that the democratic resistance movement, Review of Korean Films in 2007 (the Gwangju Democratization Movement) which occurred in Gwangju, a local city of Korea, in May 1980, would be used as source material for a Korean blockbuster in 2007. Although the film does not have any particularly profound vision about the event or the and the Outlook for 2008 period, <May 18> won over many of the public with its universal life stories and the emotions of the Gwangju citizenry during those days, and was admired for its thorough and meticulous research efforts.