World Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desarrollo Del Campo De La Historieta Argentina: Entre La Dependencia Y

REVISTA ACADÉMICA DE LA FEDERACIÓN LATINOAMERICANA DE FACULTADES DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL ISSN: 1995 - 6630 Desarrollo del campo de la historieta argentina. Entre la dependencia y la autonomía Roberto von Sprecher Argentina [email protected] Roberto von Sprecher (Allen, Argentina, 1951). Doctor en Ciencias de la Información. Docente en la Universidad Nacional de Córdoba: Teorías Sociológicas I (Los clásicos), Sociología de la Historieta Realista, Teoría Social Contemporánea, Comunicaci ón y Trabajo Social. Director del Proyecto de Investigación Historietas realistas argentinas: estudios y estado del campo. Dirige la revista digital Estudios y Crítica de la Historieta Argentina (http://historietasargentinas.wordpress.com/). Libros: La Red Comunicacional, El Eternauta: la Sociedad como Imposible, en colaboración dos volúmenes sobre Teorías Sociológicas, etc Resumen: Analizamos el campo de la historieta realista argentina. Esto implica prestar atención a los factores estructurales, considerando que la historieta nace como parte de la industria cultural y dependiente del campo del mercado. Pero también damos importancia a las prácticas de construcción de los actores que forman parte del campo y que, en determinadas situaciones históricas, introducen modificaciones importantes y momentos de alta autonomía de lo económico. Destacamos el período de la segunda mitad los cincuentas con la aparición de la historieta de autor, la dictadura y la apertura democrática y, desde los noventa, la historieta independiente. Abstract: we analyze the field of the realistic Argentine comics. This implies to attend the structural factors, considering that comics were born as part of the cultural industry and subordinated to the market field. But also we give importance to the actors construction practices, as a part of the field, who, in certain historical situations, introduce important modifications and moments of high autonomy of the economic field. -

O(S) Fã(S) Da Cultura Pop Japonesa E a Prática De Scanlation No Brasil

UNIVERSIDADE TUIUTI DO PARANÁ Giovana Santana Carlos O(S) FÃ(S) DA CULTURA POP JAPONESA E A PRÁTICA DE SCANLATION NO BRASIL CURITIBA 2011 GIOVANA SANTANA CARLOS O(S) FÃ(S) DA CULTURA POP JAPONESA E A PRÁTICA DE SCANLATION NO BRASIL Dissertação apresentada no Programa de Mestrado em Comunicação e Linguagens na Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná, na Linha Estratégias Midiáticas e Práticas Comunicacionais, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre, sob orientação do Prof. Dr. Francisco Menezes Martins. CURITIBA 2011 2 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO Giovana Santana Carlos O(S) FÃ(S) DA CULTURA POP JAPONESA E A PRÁTICA DE SCANLATION NO BRASIL Esta dissertação foi julgada e aprovada para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Comunicação e Linguagens no Programa de Pós-graduação em Comunicação e Linguagens da Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná. Curitiba, 27 de maio de 2011. Programa de pós-graduação em Comunicação e Linguagens Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná Orientador: Prof. Dr. Francisco Menezes Martins Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná Prof. Dr. Carlos Alberto Machado Universidade Estadual do Paraná Prof. Dr. Álvaro Larangeira Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Aos meus pais, Carmen Dolores Santana Carlos e Vilson Antonio Carlos, e à Leda dos Santos, por me apoiarem durante esta pesquisa; À minha irmã, Vivian Santana Carlos, por ter me apresentado a cultura pop japonesa por primeiro e por dar conselhos e ajuda quando necessário; Aos professores Dr. Álvaro Larangeira e Dr. Carlos Machado por terem acompanhado desde o início o desenvolvimento deste trabalho, melhorando-o através de sugestões e correções. À professora Dr.ª Adriana Amaral, a qual inicialmente foi orientadora deste projeto, por acreditar em seu objetivo e auxiliar em sua estruturação. -

Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender Kazue Harada Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2015 Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender Kazue Harada Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the East Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Harada, Kazue, "Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender" (2015). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 442. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/442 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of East Asian Languages & Cultures Dissertation Examination Committee: Rebecca Copeland, Chair Nancy Berg Ji-Eun Lee Diane Wei Lewis Marvin Marcus Laura Miller Jamie Newhard Japanese Women’s Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender by Kazue Harada A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 St. Louis, Missouri © 2015, Kazue Harada -

Drawn&Quarterly

DRAWN & QUARTERLY spring 2012 catalogue EXCERPT FROM GUY DELISLE’S JERUSALEM EXCERPT FROM GUY DELISLE’S JERUSALEM EXCERPT FROM GUY DELISLE’S JERUSALEM CANADIAN AUTHOR GUY DELISLE JERUSALEM Chronicles from the Holy City Acclaimed graphic memoirist Guy Delisle returns with his strongest work yet, a thoughtful and moving travelogue about life in Israel. Delisle and his family spent a year in East Jerusalem as part of his wife’s work with the non-governmental organiza- tion Doctors Without Borders. They were there for the short but brutal Gaza War, a three-week-long military strike that resulted in more than 1000 Palestinian deaths. In his interactions with the emergency medical team sent in by Doctors Without Borders, Delisle eloquently plumbs the depths of the conflict. Some of the most moving moments in Jerusalem are the in- teractions between Delisle and Palestinian art students as they explain the motivations for their work. Interspersed with these simply told, affecting stories of suffering, Delisle deftly and often drolly recounts the quotidian: crossing checkpoints, going ko- sher for Passover, and befriending other stay-at-home dads with NGO-employed wives. Jerusalem evinces Delisle’s renewed fascination with architec- ture and landscape as political and apolitical, with studies of highways, villages, and olive groves recurring alongside depictions of the newly erected West Bank Barrier and illegal Israeli settlements. His drawn line is both sensitive and fair, assuming nothing and drawing everything. Jerusalem showcases once more Delisle’s mastery of the travelogue. “[Delisle’s books are] some of the most effective and fully realized travel writing out there.” – NPR ALSO AVAILABLE: SHENZHEN 978-1-77046-079-9 • $14.95 USD/CDN BURMA CHRONICLES 978-1770460256 • $16.95 USD/CDN PYONGYANG 978-1897299210 • $14.95 USD/CDN GUY DELISLE spent a decade working in animation in Europe and Asia. -

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014 - August 2016 *To search for items, please press Ctrl + F and enter the title in the search box at the top right hand corner or at the bottom of the screen. LEGEND : BK - Book; AL - Adult Library; YPL - Children Library; AV - Audiobooks; FIC - Fiction; ANF - Adult Non-Fiction; Bio - Biography/Autobiography; ER - Early Reader; CFIC - Picture Books; CC - Chapter Books; TOD - Toddlers; COO - Cookbook; JFIC - Junior Fiction; JNF - Junior Non Fiction; POE -Children's Poetry; TRA - Travel Guide Type Location Collection Call No Title AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GIL Big magic : Creative living / Elizabeth Gilbert. AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GRA Originals : How non-conformists move the world / Adam Grant. Irrationally yours : On missing socks, pick up lines, and other existential puzzles / Dan AV AL ANF CD 153.4 ARI Ariely. Think like a freak : The authors of Freakonomics offer to retrain your brain /Steven D. AV AL ANF CD 153.43 LEV Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner. AV AL ANF CD 153.8 DWE Mindset : The new psychology of success / Carol S. Dweck. The geography of genius : A search for the world's most creative places, from Ancient AV AL ANF CD 153.98 WEI Athens to Silicon Valley / Eric Weiner. AV AL ANF CD 158 BRO Rising strong / Brene Brown. AV AL ANF CD 158 DUH Smarter faster better : The secrets of prodctivity in life and business / Charles Duhigg. AV AL ANF CD 158.1 URY Getting to yes with yourself and other worthy opponents / William Ury. 10% happier : How I tamed the voice in my head, reduced stress without losing my edge, AV AL ANF CD 158.12 HAR and found self-help that actually works - a true story / Dan Harris. -

Tatsumi Premieres at the 64Th Cannes Film Festival 2011

TATSUMI PREMIERES AT THE 64TH CANNES FILM FESTIVAL 2011 B A SED ON "A DRIFTING L IFE" AND THE SHORT STORIES OF YOSHIHIRO TATSUMI “Cannes was my dream of dreams. My heart swells with joy and pride, knowing that "TATSUMI" will premiere there. I just want to toast Eric Khoo!!” Yoshihiro Tatsumi “It has been my dream for this to happen, that Tatsumi premieres at Cannes Official Selection so that Yoshihiro Tatsumi, someone I truly admire and love, will finally be on one of the biggest international platforms to share Gekiga, his life and stories with the entire world.” Eric Khoo, Director "We are proud and honored at Infinite Frameworks to have had the opportunity to work on Tatsumi san's legendary artwork and to bring it to life under Eric's unique vision. It is by far the most emotional journey we have undertaken as a studio and the experience will continue to shape us for years to come." Mike Wiluan, Executive Producer TATSUMI PRESS RELEASE 14 APR 2011 Page 0 "It’s been an amazing journey composing for my dad. Starting off in 2008 with the movie, My Magic. I thought it would be a one time thing, but since music meant so much, I decided to continue and will never regret it. The three pieces from Tatsumi, after the arrangement by Christine Sham, have come a long way, and I love each and everyone of them." Christopher Khoo, Composer Yoshihiro Tatsumi started the gekiga movement, because he was heavily influenced by cinema. It's poetically fitting that Eric Khoo has decided to honour this master and his vision by making this film; things have just come full circle. -

To Outsmart an Alien Study of Comics As a Narrational Medium

Faculty of New Media Arts Graphic Design 2D Visualisation Inga Siek S17419 Bachelor diploma work To Outsmart An Alien Matt Subieta Chief Supervisor Marcin Wichrowski Technical Supervisor Study of Comics as a Narrational Medium Anna Machwic Theoretical Supervisor Klaudiusz Ślusarczyk Language Supervisor Warsaw, July, 2020 1 Wydział Nowych Mediów Grafika Komputerowa Wizualizacja 2D Inga Siek S17419 Praca Licencjacka Przechytrzyć Kosmitę Matt Subieta Główny Promotor Marcin Wichrowski Techniczny Promotor Badanie Komiksów jako Medium Narracji Anna Machwic Teoretyczny Promotor Klaudiusz Ślusarczyk Promotor Językowy Warszawa, Lipiec, 2020 2 This thesis is dedicated to the study and analysis of comics, both in terms of history and practice, as well as it is an attempt to change the common view of the practice as immature and primitive. In order to develop a good understanding of what comics are and their origins, this work starts by giving the reader a quick historical overview of the genre and its predecessor, sequential art. The reader will learn not only about the roots of comic illustration design but also its modern influences. The paper will refer to major names in the industry, and well as identify important historical events, both of which helped steer comics into the direction they are today. Additionally, descriptions of the main elements of comics will be provided. The last chapter will supply a number of examples in the utilizations of comic design components that include story, characters, panels and text by different artists who helped shape the craft of comics, and hopefully this will inspire the reader as well as provoke them to start viewing comics in a different, or perhaps even more positive light. -

Foreign Rights Guide Bologna 2019

ROCHETTE LE LOUP FOREIGN RIGHTS GUIDE BOLOGNA 2019 FOREIGN RIGHTS GUIDE BOLOGNE 2019 CONTENTS MASTERS OF COMICS GRAPHIC NOVELS BIOPICS • NON FICTION ADVENTURE • HISTORY SCIENCE FICTION • FANTASY HUMOUR LOUVRE ALL-AGES COMICS TINTIN ET LA LUNE – OBJECTIF LUNE ET ON A MARCHÉ SUR LA LUNE HERGÉ On the occasion of the 90th anniversary of Tintin and the 50th anniversary of the first step on the Moon, Tintin’s two iconic volumes combined in a double album. In Syldavia, Professor Calculus develops its motor atomic lunar rocket and is preparing to leave for the Moon. But mysterious incidents undermine this project: the test rocket is diverted, an attempt to steal plans occurs... Who is hiding behind this ? And will the rocket be able to take off ? We find our heroes aboard the first lunar rocket. But the flight is far from easy: besides the involuntary presence of Thompson and Thomson (which seriously limits the oxygen reserves), saboteurs are also on board. Will the rocket be back on Earth in time ? 240 x 320 • 128 pages • Colours • 19,90 € Publication : May 2019 90 YEARS OF ADVENTURES! Also Available MASTERS OF COMICS COMPLETE SERIES OF TINTIN HERGÉ MASTERS OF COMICS CORTO MALTESE – VOL. 14 EQUATORIA CANALES / PELLEJERO / PRATT Aft er a bestselling relaunch, the next adventure from Canales and Pellejero is here… It is 1911 and Corto Maltese is in Venice, accompanied by the National Geographic journalist Aïda Treat, who is hoping to write a profi le of him. Attempting to track down a mysterious mirror once owned by Prester John, Corto soon fi nds himself heading for Alexandria. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

An Examination of Superhero Tropes in My Hero Academia

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-29-2020 The World’s Greatest Hero: An Examination of Superhero Tropes in My Hero Academia Jerry Waller [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Waller, Jerry, "The World’s Greatest Hero: An Examination of Superhero Tropes in My Hero Academia" (2020). Master's Projects and Capstones. 1006. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/1006 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The World’s Greatest Hero: An Examination of Superhero Tropes in My Hero Academia Jerry Waller APS 650: MAPS Capstone Seminar May 17, 2020 1 Abstract In this paper the author explores the cross-cultural transmission of genre archetypes in illustrated media. Specifically, the representation of the archetype of American superheroes as represented in the Japanese manga and anime series, My Hero Academia. Through examination of the extant corpus of manga chapters and anime episodes for the franchise, the author draws comparison between characters and situations in the manga series with examples from American comic books by Marvel Comics and DC Comics. -

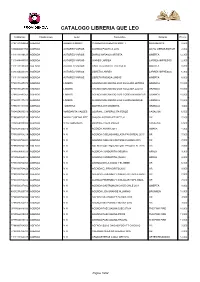

Catalogoqueleopedrodevaldivia40.Pdf

CATALOGO LIBRERIA QUE LEO CodBarras Clasificacion Autor Titulo Libro Editorial Precio 7798141020454 AGENDA ALBERTO MONTT CUADERNO ALBERTO MONTT MONOBLOCK 8,500 1000000001709 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS AGENDA POLITICA 2012 OCHO LIBROS EDITOR 2,900 1111111199121 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS DIARIO NARANJA ARTISTA OMERTA 12,300 1111444445551 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS IMANES LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 2,900 1111111198988 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA GRANATE CALCULO OMERTA 8,200 3333344443330 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 6,900 1111111198995 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA ROSADA LINEAS OMERTA 8,500 7798071447376 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LETRAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447390 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LLUVIA GRANICA 10,000 7798071447352 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BANDERAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447338 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BOSQUE GRANICA 10,000 7798071444399 AGENDA . MAITENA MAITENA 007 MAGENTA GRANICA 1,000 7804654930019 AGENDA MARGARITA VALDES JOURNAL, CAPERUCITA FEROZ VASALISA 6,500 7798083702128 AGENDA MARIA EUGENIA PITE CHUICK AGENDA PERPETUA VR 7,200 7804654930002 AGENDA NICO GONZALES JOURNAL PIZZA PALIZA VASALISA 6,500 7804634920016 AGENDA N N AGENDA AMAKA 2011 AMAKA 4,900 7798083704214 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO ANILLADA PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704221 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE FLORES 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704238 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 9789568069025 AGENDA N N AGENDA CONDORITO (NEGRA) ORIGO 9,900 9789568069032 AGENDA -

The Secrets of Venice

Corto Maltese® & Hugo Pratt™ the secrets are © Cong SA. of venice... All rights reserved. the AdVENTURE! © Cong SA / Casterman THE SECRETS OF VENICE from “Fable of Venice” THE QUEST ON THIS ADVENTURE ADVENTURE Fable of Venice takes place in 1921 and is divided into four chapters. The background of the story Some places in Venice can reveal hidden CARDS is the rise of facism in Italy in the aftermath of the First World War. In this book, Hugo Pratt treasures… • 13 “character” cards shares some of his childhood memories and, as he often does, takes the reader into a true When the game is over, each “character” card • 3 “object” cards adventure novel. • 1 “advantage” card placed on a space with gold coins is worth that Under the watchful eyes of the god Abraxas, the masonic lodges and the facist militias, • 2 “Corto” cards much gold to the player controlling it. Corto Maltese, who came to Venice to solve a riddle given to him by his friend Baron Corvo, is • 1 “Rasputin” card tracking down the “Clavicle of Solomon”, a legendary emerald. In this story, full of suspens and unexpected events and which will eventually end in a dream, Corto will let us discover mysterious women, fallen aristocrats, “Blackshirts”, and magical places of Venice. In this example, the blue player gains 3 gold, green and yellow gain nothing. Bepi Faliero TEONE Louise Umberto Astronomer, astrologer and Brookszowyc Stevani mathematician, this master Better known as “the Beauty A young facist, member of of the occult sciences is also of Milano”, this friend of the Blackshirts of Venice.