Manga and the Graphic Novel, According to a List of Key Discursive Characteristics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Probing the Manga Topoet(H)Ics in Tezuka's Message to Adolf

Ana Došen Probing the Manga ToPoEt(h)ics in Tezuka’s Message to Adolf Keywords: manga, spatial turn, topography, poetics, ethics Manga and Spatial Turn The postmodern era has seen both global fragmentation and unification occurring simultaneously, resulting in multiple notions of space and theo- retical frameworks. Through not only cultural and critical geography, but also literary geography and cartography, a new understanding of spatiality has emerged. With the so-called spatial turn, established theoretical per- spectives concerning the time-space continuum are being re-evaluated, and the complex issue of topography is regaining relevance. The repre- sentation of space in literary works brings into focus multiple opportuni- ties to develop new, decolonizing and non-normative spatial imageries. Instead of the previously dominating historicism, the spatial turn as an interdisciplinary perspective allows one to deconstruct and reconstruct categories of space and place while overcoming previously established spatial dichotomies such as East/West, far/near, periphery/center. The observations of prominent thinkers such as Michel Foucault (1997) con- tributed to an understanding of space as something other than a fixed category. Conceptual “de-territorialization” and “re-territorialization” has affected issues of identity and borders, including the epistemological basis of area studies. Engagement in area studies, as a form of spatial scholarship, has traditionally been focused on national, regional and local characteristics, but it has also become apparent that it involves complex transrelational aspects: between the space of the subject matter and the place of its criti- cal exploration. Globalized political, cultural and economic entangle- ments are also reflected in area studies, as boundaries that once seemed separate and solid can now be traversed. -

Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime

SAN DIEGO PUBLIC LIBRARY PATHFINDER Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime The Central Library has a large collection of comics, the Usual Extra Rarities, 1935–36 (2005) by George graphic novels, manga, anime, and related movies. The Herriman. 741.5973/HERRIMAN materials listed below are just a small selection of these items, many of which are also available at one or more Lions and Tigers and Crocs, Oh My!: A Pearls before of the 35 branch libraries. Swine Treasury (2006) by Stephan Pastis. GN 741.5973/PASTIS Catalog You can locate books and other items by searching the The War Within: One Step at a Time: A Doonesbury library catalog (www.sandiegolibrary.org) on your Book (2006) by G. B. Trudeau. 741.5973/TRUDEAU home computer or a library computer. Here are a few subject headings that you can search for to find Graphic Novels: additional relevant materials: Alan Moore: Wild Worlds (2007) by Alan Moore. cartoons and comics GN FIC/MOORE comic books, strips, etc. graphic novels Alice in Sunderland (2007) by Bryan Talbot. graphic novels—Japan GN FIC/TALBOT To locate materials by a specific author, use the last The Black Diamond Detective Agency: Containing name followed by the first name (for example, Eisner, Mayhem, Mystery, Romance, Mine Shafts, Bullets, Will) and select “author” from the drop-down list. To Framed as a Graphic Narrative (2007) by Eddie limit your search to a specific type of item, such as DVD, Campbell. GN FIC/CAMPBELL click on the Advanced Catalog Search link and then select from the Type drop-down list. -

The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals By

Comics Aren’t Just For Fun Anymore: The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals by David Recine A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in TESOL _________________________________________ Adviser Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date University of Wisconsin-River Falls 2013 Comics, in the form of comic strips, comic books, and single panel cartoons are ubiquitous in classroom materials for teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL). While comics material is widely accepted as a teaching aid in TESOL, there is relatively little research into why comics are popular as a teaching instrument and how the effectiveness of comics can be maximized in TESOL. This thesis is designed to bridge the gap between conventional wisdom on the use of comics in ESL/EFL instruction and research related to visual aids in learning and language acquisition. The hidden science behind comics use in TESOL is examined to reveal the nature of comics, the psychological impact of the medium on learners, the qualities that make some comics more educational than others, and the most empirically sound ways to use comics in education. The definition of the comics medium itself is explored; characterizations of comics created by TESOL professionals, comic scholars, and psychologists are indexed and analyzed. This definition is followed by a look at the current role of comics in society at large, the teaching community in general, and TESOL specifically. From there, this paper explores the psycholinguistic concepts of construction of meaning and the language faculty. -

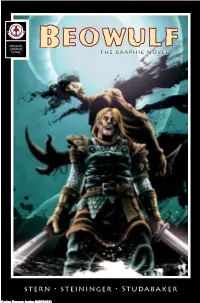

Beowulf: the Graphic Novel Created by Stephen L

ORIGINAL GRAPHIC NOVEL THE GRAPHIC NOVEL TUFSOtTUFJOJOHFSt4UVEBCBLFS Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Writer Stephen L. Stern Artist Christopher Steininger Letterer Chris Studabaker Cover Christopher Steininger For MARKOSIA ENTERPRISES, Ltd. Harry Markos Publisher & Managing Partner Chuck Satterlee Director of Operations Brian Augustyn Editor-In-Chief Tony Lee Group Editor Thomas Mauer Graphic Design & Pre-Press Beowulf: The Graphic Novel created by Stephen L. Stern & Christopher Steininger, based on the translation of the classic poem by Francis Gummere Beowulf: The Graphic Novel. TM & © 2007 Markosia and Stephen L. Stern. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction of any part of this work by any means without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden. Published by Markosia Enterprises, Ltd. Unit A10, Caxton Point, Caxton Way, Stevenage, UK. FIRST PRINTING, October 2007. Harry Markos, Director. Brian Augustyn, EiC. Printed in the EU. Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 Beowulf: The Graphic Novel An Introduction by Stephen L. Stern Writing Beowulf: The Graphic Novel has been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my career. I was captivated by the poem when I first read it decades ago. The translation was by Francis Gummere, and it was a truly masterful work, retaining all of the spirit that the anonymous author (or authors) invested in it while making it accessible to modern readers. “Modern” is, of course, a relative term. The Gummere translation was published in 1910. Yet it held up wonderfully, and over 60 years later, when I came upon it, my imagination was captivated by its powerful descriptions of life in a distant place and time. -

Lone Wolf and Cub Volume 24: in These Small Hands Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LONE WOLF AND CUB VOLUME 24: IN THESE SMALL HANDS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kazuo Koike,Goseki Kojima | 320 pages | 10 Sep 2002 | Dark Horse Comics,U.S. | 9781569715963 | English | Milwaukie, United States Lone Wolf and Cub Volume 24: In These Small Hands PDF Book The Yagyu letter plot has also advanced here. Jan 28, Ill D rated it it was amazing Recommends it for: Japanophiles. About the Author Kazuo Koike is a prolific Japanese manga writer, novelist, and entrepreneur. Randy Stradley. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Ben Wong rated it really liked it Feb 12, Drug and Drop Volume 2. A samurai epic of staggering proportions, the acclaimed Lone Wolf and Cub begins its second Please try again later. Publisher: Dark Horse Comics. So, in these final days, a ronin and his young boy will visit the grave of their murdered wife and mother. Koike, along with artist Goseki Kojima, made the manga Kozure Okami Lone Wolf and Cub , and Koike also contributed to the scripts for the s film adaptations of the series, which starred famous Japanese actor Tomisaburo Wakayama. When you buy a book, we donate a book. Eventually, the two opposing master swordsmen dry off and go head to head in a sword fight of a thousand stances and couple of days length. Dark Horse respects your privacy. It just might be the last Spring the two will share, like the many petals falling from branches. Start your review of Lone Wolf and Cub, Vol. By using digital. Yoshiki Tanaka. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. -

Manga Book Club Handbook

MANGA BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for manga! STAFF COMIC Director’sBOOK LEGAL Note Charles Brownstein, Executive Director DEFENSE FUND Alex Cox, Deputy Director Everything is changing in 2016, yet the familiar challenges of the past continueBetsy to Gomez, Editorial Director reverberate with great force. This isn’t just true in the broader world, but in comics,Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor too. While the boundaries defining representation and content in free expression are protectingexpanding, wethe continue freedom to see to biasedread comics!or outmoded Our viewpoints work protects stifling those advances.Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- STAFF As you’ll see in this issue of CBLDF Defender, we are working on both ends of the Charles Brownstein, Executive Director torsspectrum who byface providing the threat vital educationof censorship. about the We people monitor whose worklegislation expanded free exBOARD- Alex OF Cox, DIRECTORS Deputy Director pression while simultaneously fighting all attempts to censor creative work in comics.Larry Marder,Betsy Gomez, President Editorial Director and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. Maren Williams, Contributing Editor In this issue, we work the former end of the spectrum with a pair of articles spotlightMilton- Griepp, Vice President We create resources that promote understanding of com- Jeff Abraham,Caitlin McCabe,Treasurer Contributing Editor ing the pioneers who advanced diverse content. On page 10, “Profiles in Black Cartoon- Dale Cendali,Robert SecretaryCorn-Revere, Legal Counsel icsing” and introduces the rights you toour some community of the cartoonists is guaranteed. -

Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1 | Epub

Shogunate executioner Ogami Itto is framed as a traitor by the agents from a rival clan. With his wife murdered and with an infant son to protect, Ogami chooses the path of the ronin, the masterless samurai. The Lone Wolf and Cub wander feudal Japan, Ogami's sword for hire, but all roads will lead them to a single destination: vengeance.A samurai epic of staggering proportions, the acclaimed Lone Wolf and Cub begins its second life at Dark Horse Manga with new, larger editions of over 700 pages, value priced. The brilliant storytelling of series creator Kazuo Koike and the groundbreaking cinematic visuals of Goseki Kojima create a graphic-fiction masterpiece of beauty, fury, and thematic power.This volume collects material previously published in Dark Horse graphic novels Lone Wolf and Cub, Vol. 1: The Assassin's Road, Lone Wolf and Cub, Vol. 2: The Gateless Barrier, Lone Wolf and Cub, Vol. 3: The Flute of the Fallen Tiger Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1 by , Read PDF Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1 Online, Read PDF Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1, Full PDF Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1, All Ebook Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1, PDF and EPUB Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1, PDF ePub Mobi Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1, Reading PDF Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1, Book PDF Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1, Download online Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1, Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1 pdf, by Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1, book pdf Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 1, by pdf Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus -

Graphic Gothic Introduction Julia Round

Graphic Gothic Introduction Julia Round ‘Graphic Gothic’ was the seventh International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference, held at Manchester Metropolitan University in June 2016.1 The event brought together fifty scholars from all over the globe, who explored Gothic under themes such as setting, politics, adaptation, censorship, monstrosity, gender, and corporeality. This issue of Studies in Comics collects selected papers from the conference, alongside expanded versions of the talks given by three of our four keynote speakers: Hannah Berry, Toni Fejzula and Matt Green. It is complemented by a comics section that recalls the conference and reflects the potential of Gothic to inform and inspire as Paul Fisher Davies provides a sketchnoted diary of the event. Defining the Gothic is a difficult task. Baldick and Mighall (2012: 273) note that much of the relevant scholarship to date has primarily applied ‘the broadest kind of negation: the Gothic is cast as the opposite of Enlightenment reason, as it is the opposite of bourgeois literary realism.’ Moers also suggests that the meaning of Gothic ‘is not so easily stated except that it has to do with fear’ (1978: 90). Many Gothic scholars and writers have explored the nature of this fear: attempting to draw out and categorise the metaphorical meanings and affect it can create. H.P. Lovecraft (1927: 41) claims that ‘The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind fear of the unknown’ (Lovecraft 1927: 41) and that this is the basis for ‘the weirdly horrible tale’ as a literary form. Ann Radcliffe (1826: 5) famously separates terror and horror, and later writers and critics such as Devendra Varma (1957), Robert Hume (1969), Stephen King (1981), Gina Wisker and Dale Townshend continue to explore this divide. -

Manga As a Teaching Tool 1

Manga as a Teaching Tool 1 Manga as a Teaching Tool: Comic Books Without Borders Ikue Kunai, California State University, East Bay Clarissa C. S. Ryan, California State University, East Bay Proceedings of the CATESOL State Conference, 2007 Manga as a Teaching Tool 2 Manga as a Teaching Tool: Comic Books Without Borders The [manga] titles are flying off the shelves. Students who were not interested in EFL have suddenly become avid readers ...students get hooked and read [a] whole series within days. (E. Kane, personal communication, January 17, 2007) For Americans, it may be difficult to comprehend the prominence of manga, or comic books, East Asia.1. Most East Asian nations both produce their own comics and publish translated Japanese manga, so Japanese publications are popular across the region and beyond. Japan is well-known as a highly literate society; what is less well-known is the role that manga plays in Japanese text consumption (Consulate General of Japan in San Francisco). 37% of all publications sold in Japan are manga of one form or another, including monthly magazines, collections, etc. (Japan External Trade Organization [JETRO], 2006). Although Japan has less than half the population of the United States, manga in all formats amounted to sales within Japan of around 4 billion dollars in 2005 (JETRO, 2006). This total is about seven times the United States' 2005 total comic book, manga, and graphic novel sales of 565 million dollars (Publisher's Weekly, 2007a, 2007b). Additionally, manga is closely connected to the Japanese animation industry, as most anime2 television series and films are based on manga; manga also provides inspiration for Japan's thriving video game industry. -

Korean Webtoons' Transmedia Storytelling

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), 2094–2115 1932–8036/20190005 Snack Culture’s Dream of Big-Screen Culture: Korean Webtoons’ Transmedia Storytelling DAL YONG JIN1 Simon Fraser University, Canada The sociocultural reasons for the growth of webtoons as snack culture and snack culture’s influence in big-screen culture have received little scholarly attention. By employing media convergence supported by transmedia storytelling as a theoretical framework alongside historical and textual analyses, this article historicizes the emergence of snack culture. It divides the evolution of snack culture—in particular, webtoon culture—to big-screen culture into three periods according to the surrounding new media ecology. Then it examines the ways in which webtoons have become a resource for transmedia storytelling. Finally, it addresses the reasons why small snack culture becomes big-screen culture with the case of Along With the Gods: The Two Worlds, which has transformed from a popular webtoon to a successful big-screen movie. Keywords: snack culture, webtoon, transmedia storytelling, big-screen culture, media convergence Snack culture—the habit of consuming information and cultural resources quickly rather than engaging at a deeper level—is becoming representative of the Korean cultural scene. It is easy to find Koreans reading news articles or watching films or dramas on their smartphones on a subway. To cater to this increasing number of mobile users whose tastes are changing, web-based cultural content is churning out diverse subgenres from conventional formats of movies, dramas, cartoons, and novels (Chung, 2014, para. 1). The term snack culture was coined by Wired in 2007 to explain a modern tendency to look for convenient culture that is indulged in within a short duration of time, similar to how people eat snacks such as cookies within a few minutes. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Fiction – January, 2017

FICTION – JANUARY, 2017 Ackerman, Elliot, Dark at the crossing / Elliot Ackerman. FICTION ACK Adiga, Aravind, Selection day / Aravind Adiga. FICTION ADI Appelfeld, Aharon, The man who never stopped sleeping / Aharon Appelfeld ; Translated from the Hebrew by Jeffrey M. Green. FICTION APP Arden, Katherine, The bear and the nightingale / Katherine Arden. FICTION ARD Auster, Paul, 1947- 4 3 2 1 / Paul Auster. FICTION AUS Barry, Brunonia, The fifth petal / Brunonia Barry. FICTION BAR Berenson, Alex, The prisoner / Alex Berenson. FICTION BER In sunlight or in shadow : stories inspired by the paintings of Edward Hopper / edited by Lawrence Block. FICTION IN Bohjalian, Chris, 1960- The sleepwalker / by Chris Bohjalian. FICTION BOH Burnet, Graeme Macrae, 1967- His bloody project : documents relating to the case of Roderick Macrae, a historical thriller / edited and introduced by Graeme Macrae Burnet. FICTION BUR Coe, Jonathan, Number 11 / Jonathan Coe. FICTION COE Coover, Robert, Huck out west / Robert Coover. FICTION COO Cusk, Rachel, 1967- Transit / Rachel Cusk. FICTION CUS D'Agostino, Kris, 1978- The antiques / Kris D'Agostino. FICTION D'AG Nightmares : a new decade of modern horror / edited by Ellen Datlow. FICTION NIG Doctorow, E. L., 1931-2015, Doctorow : collected stories / E.L. Doctorow. FICTION DOC Ellis, Janet, The butcher's hook / Janet Ellis. FICTION ELL Forstchen, William R., The final day / William R. Forstchen. FICTION FOR Frankel, Laurie, This is how it always is / Laurie Frankel. FICTION FRA Fridlund, Emily, History of wolves / Emily Fridlund. FICTION FRI Gardner, Lisa, Right behind you / Lisa Gardner. FICTION GAR Gay, Roxane, Difficult women / Roxane Gay. FICTION GAY Gilligan, Ruth, Nine folds make a paper swan / Ruth Gilligan.