The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

A Visual-Textual Analysis of Sarah Glidden's

BLACKOUTS MADE VISIBLE: A VISUAL-TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF SARAH GLIDDEN’S COMICS JOURNALISM _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial FulfillMent of the RequireMents for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by TYNAN STEWART Dr. Berkley Hudson, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have exaMined the thesis entitleD BLACKOUTS MADE VISIBLE: A VISUAL-TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF SARAH GLIDDEN’S COMICS JOURNALISM presented by Tynan Stewart, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. —————————————————————————— Dr. Berkley Hudson —————————————————————————— Dr. Cristina Mislán —————————————————————————— Dr. Ryan Thomas —————————————————————————— Dr. Kristin Schwain DEDICATION For my parents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My naMe is at the top of this thesis, but only because of the goodwill and generosity of many, many others. Some of those naMed here never saw a word of my research but were still vital to My broader journalistic education. My first thank you goes to my chair, Berkley Hudson, for his exceptional patience and gracious wisdom over the past year. Next, I extend an enormous thanks to my comMittee meMbers, Cristina Mislán, Kristin Schwain, and Ryan Thomas, for their insights and their tiMe. This thesis would be so much less without My comMittee’s efforts on my behalf. TiM Vos also deserves recognition here for helping Me narrow my initial aMbitions and set the direction this study would eventually take. The Missourian newsroom has been an all-consuming presence in my life for the past two and a half years. -

Kablegram and Shrapnel Take SIP a Honor Awards SMA Units March In

pHttWATlQHAO Wht KaMe<jram Vol. 47 Staunton Military Academy, Kable Station, Staunton, Virginia, Friday, May 8, 1964 No. 9 Kablegram And Shrapnel 180 Juniors Take SIP A Honor Awards Take MMSQT Nearly 180 juniors at Staunton Four SMA cadets and three faculty advisors joined 1023 Military Academy took the 1964 other students and teachers last weekend for the 35th annual National Merit Scholarship Quali- Southern Inlerscholastic Press Association Convention. The fying Test recently. meeting was held May 1, 2, 3, on the campus of Washington The qualifying test is a three- and Lee University at Lexington, Virginia. hour examination of educational Newspapers, magazines, and yearbooks from 183 schools development. The test is the first step in the tenth annual competi- in eight states were judged. tion for four-year Merit Scholar- SMA's Kablegram and Shrapnel won Honor Awards. A ships provided by the National first place award is the highest category: honor is the inter- Merit Scholarship Corporation and mediate one. Achievement award is a lower one. by sponsoring corporations, foun- The Scimitar, SMA's general interest magazine, was eval- dations, colleges, associations, un- ions, trusts, and individuals. uated, but no ratings were given. The number of scholarships The Southern Interscholastic Press Association Conven- awarded in any year depends upon tion offers classes and workshops for the delegates, followed the extent of sponsor participa- by critiques of t'he publications. tion. In 1963, 1528 Merit Scholar- They led ns at Winchester — SMA's Color Guard: Poole, ships were awarded; 951 were pro- CHILDS, FEATURED SPEAKER Weeks, Dalton, and Weston. -

La Bande Dessinée Dans La Même Collection Vers La Vidéo-Animation Pour Une Pédagogie De L'audio-Visuel Initiation À La Sémiologie Du Récit En Images Jacques'zimmer

la bande dessinée dans la même collection vers la vidéo-animation pour une pédagogie de l'audio-visuel initiation à la sémiologie du récit en images jacques'zimmer la bande dessinée les cahiers de l'audio-visuel Dessin de couverture de Jean-François Millet Tous droits de reproduction même partielle par quelque procédé que ce soit réservés pour tous pays. Copyright by Ligue française de l'enseignement et de l'éducation permanente. La bande dessinée n'a plus besoin de défenseurs : le temps n'est plus où toute préface se devait d'être nostalgique, agressive ou lyrique. Le temps n'est plus des rudes affrontements entre procureurs hargneux et avocats apologétiques. La B.D. est unanimement reconnue comme langage et chacun sait, depuis Esope que la langue charrie le pire et le meilleur : comme le cinéma, la télévision, la presse, le livre de poche, la bande dessinée est un phénomène de surconsommation. Les mass media véhicu- lent, via l'information, les idéologies : aux éducateurs la tâche d'apprendre à lire et à démystifier les messages. Mais, de grâce, pas « d'enseignement de la bande dessinée ». On a ouvert une chaire à la Sorbonne : je ne suis pas sûr que ce mieux ne soit pas l'ennemi du bien. A copier quinze fois : « Christophe (de son vrai nom Georges Colomb), 1856-1945, est le trait d'union entre Wilhem Bush (1832-1908) et Rudolph Dirks, créateur des Katzenjammer Kids (1895, en français « Pim Pam Poum »)... » Surtout pas ça !... Il faut introduire à l'école un moyen d'expression vivant, former des lecteurs, informer des consommateurs, utiliser l'image comme moyen pédagogique, susciter le débat, organiser le travail par groupes, ouvrir la bibliothèque de classe à ce qui est souvent encore pourchassé dans l'enceinte scolaire. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FORTY-TWO $9 95 IN THE US Guardian, Newsboy Legion TM & ©2005 DC Comics. Contents THE NEW OPENING SHOT . .2 (take a trip down Lois Lane) UNDER THE COVERS . .4 (we cover our covers’ creation) JACK F.A.Q. s . .6 (Mark Evanier spills the beans on ISSUE #42, SPRING 2005 Jack’s favorite food and more) Collector INNERVIEW . .12 Jack created a pair of custom pencil drawings of the Guardian and Newsboy Legion for the endpapers (Kirby teaches us to speak the language of the ’70s) of his personal bound volume of Star-Spangled Comics #7-15. We combined the two pieces to create this drawing for our MISSING LINKS . .19 front cover, which Kevin Nowlan inked. Delete the (where’d the Guardian go?) Newsboys’ heads (taken from the second drawing) to RETROSPECTIVE . .20 see what Jack’s original drawing looked like. (with friends like Jimmy Olsen...) Characters TM & ©2005 DC Comics. QUIPS ’N’ Q&A’S . .22 (Radioactive Man goes Bongo in the Fourth World) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .25 (creating the Silver Surfer & Galactus? All in a day’s work) ANALYSIS . .26 (linking Jimmy Olsen, Spirit World, and Neal Adams) VIEW FROM THE WHIZ WAGON . .31 (visit the FF movie set, where Kirby abounds; but will he get credited?) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .34 (Adam McGovern goes Italian) HEADLINERS . .36 (the ultimate look at the Newsboy Legion’s appearances) KIRBY OBSCURA . .48 (’50s and ’60s Kirby uncovered) GALLERY 1 . .50 (we tell tales of the DNA Project in pencil form) PUBLIC DOMAIN THEATRE . .60 (a new regular feature, present - ing complete Kirby stories that won’t get us sued) KIRBY AS A GENRE: EXTRA! . -

Sloane Drayson Knigge Comic Inventory (Without

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Number Donor Box # 1,000,000 DC One Million 80-Page Giant DC NA NA 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 A Moment of Silence Marvel Bill Jemas Mark Bagley 2002 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alex Ross Millennium Edition Wizard Various Various 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Open Space Marvel Comics Lawrence Watt-Evans Alex Ross 1999 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alf Marvel Comics Michael Gallagher Dave Manak 1990 33 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 2 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 3 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 4 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 5 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 6 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Aphrodite IX Top Cow Productions David Wohl and Dave Finch Dave Finch 2000 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 600 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 601 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 602 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 603 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 -

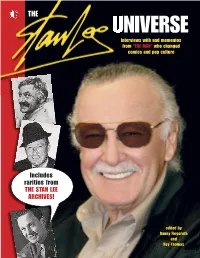

Includes Rarities from the STAN LEE ARCHIVES!

THE UNIVERSE Interviews with and mementos from “THE MAN” who changed comics and pop culture Includes rarities from THE STAN LEE ARCHIVES! edited by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas CONTENTS About the material that makes up THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE Some of this book’s contents originally appeared in TwoMorrows’ Write Now! #18 and Alter Ego #74, as well as various other sources. This material has been redesigned and much of it is accompanied by different illustrations than when it first appeared. Some material is from Roy Thomas’s personal archives. Some was created especially for this book. Approximately one-third of the material in the SLU was found by Danny Fingeroth in June 2010 at the Stan Lee Collection (aka “ The Stan Lee Archives ”) of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and is material that has rarely, if ever, been seen by the general public. The transcriptions—done especially for this book—of audiotapes of 1960s radio programs featuring Stan with other notable personalities, should be of special interest to fans and scholars alike. INTRODUCTION A COMEBACK FOR COMIC BOOKS by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas, editors ..................................5 1966 MidWest Magazine article by Roger Ebert ............71 CUB SCOUTS STRIP RATES EAGLE AWARD LEGEND MEETS LEGEND 1957 interview with Stan Lee and Joe Maneely, Stan interviewed in 1969 by Jud Hurd of from Editor & Publisher magazine, by James L. Collings ................7 Cartoonist PROfiles magazine ............................................................77 -

Customer Order Form

#355 | APR18 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE APR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Apr18 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:51:03 PM You'll for PREVIEWS!PREVIEWS! STARTING THIS MONTH Toys & Merchandise sections start with the Back Cover! Page M-1 Dynamite Entertainment added to our Premier Comics! Page 251 BOOM! Studios added to our Premier Comics! Page 279 New Manga section! Page 471 Updated Look & Design! Apr18 Previews Flip Ad.indd 1 3/8/2018 9:55:59 AM BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SWORD SLAYER SEASON 12: DAUGHTER #1 THE RECKONING #1 DARK HORSE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS THE MAN OF JUSTICE LEAGUE #1 THE LEAGUE OF STEEL #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT EXTRAORDINARY DC ENTERTAINMENT GENTLEMEN: THE TEMPEST #1 IDW ENTERTAINMENT THE MAGIC ORDER #1 IMAGE COMICS THE WEATHERMAN #1 IMAGE COMICS CHARLIE’S ANT-MAN & ANGELS #1 BY NIGHT #1 THE WASP #1 DYNAMITE BOOM! STUDIOS MARVEL COMICS ENTERTAINMENT Apr18 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:39:16 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT InSexts Year One HC l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Lost City Explorers #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Carson of Venus: Fear on Four Worlds #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Archie’s Super Teens vs. Crusaders #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Solo: A Star Wars Story: The Official Guide HC l DK PUBLISHING CO The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide Volume 48 SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Mae Volume 1 TP l LION FORGE 1 A Tale of a Thousand and One Nights: Hasib & The Queen of Serpents HC l NBM Shadow Roads #1 l ONI PRESS INC. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Electricomics Project Report.Pdf

Madefire Sequential Comixology Bouletcorp.com The writer creates a script, sometimes just from notes, or sometimes from rough sketches of the page called thumbnails. This thumbnail for Big Nemo shows that Alan Moore planned his page out as a traditional comic page, even though he knew he wanted the panels of it to only be visible one at a time. Below, we can see Moore’s script for the first two panels which features directions for the artist, as well as sound directions, and also what transitions there might be for the balloons and captions. All the writers had to make the choice of what to direct and what not to. They mostly put in a ‘wishlist’ which they were happy to see pared down, as the practicalities of those things were weighed against the time frame of the project. PANEL 1. In the blackness, we have SOUND F.X. of gentle snoring and whistling, bedroom ambience. After a second or two, the first caption appears up towards the top left corner of the top quarter-page space on the screen. The caption is reversed-out white on black, and is in a suitably fancy 1920s font. CAPTION: NEW YORK, 1929. PANEL 2. After a moment, the caption fades from sight. On the SOUND F.X. we have the snoring and whistling suddenly cease in the sound of a child falling out of bed and clattering to the floor. Then, in the lower left quarter of the bottom panel-space, we have a standard small black and white line image of McKay’s Little Nemo having just fallen out of his bed, which we see the top part of directly behind him. -

Dragon-Con-2019-Comics-Pop-Art

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Dan Carroll, Director, Media Engagement Phone: 404 692 1958 Email: [email protected] URL: www.dragoncon.org DRAGON CON’S COMICS & POP ART TRACK EXPANDS TO WELCOME FANS OF ALL AGES. Comic & Pop Artist Alley Boasts a Guest Roster of Industry Veterans and New Talent, Workshops for Children and Adults, and Amplified Kids Programming at Dragon Con. ATLANTA – July 24, 2019 – Dragon Con, Atlanta’s internaonally-known pop culture, fantasy, science ficon, and gaming convenon, will be broadening its Comics & Pop Art programming to encourage art and comic enthusiasts of all ages. In addion to a dream team of Bronze Age and Modern Age comics writers and arsts, the convenon’s tradional strength, the convenon has added workshops and other programming designed to help aspiring comics creators and to encourage greater interest from today’s younger generaons. Marv Wolfman, Roy Thomas, and Fabien Nicieza lead this year’s guest list. Thomas, a legendary writer and editor in his own right, is best recognized as Stan Lee’s first successor as editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics. Nicieza's work includes wring and eding for Marvel, DC, and Dark Horse comics, but fans will also know him as the co-creator of Deadpool. Writer and co-creator of The New Teen Titans , Wolfman also joins George Pérez, his work partner of over 40 years, at this year’s convenon. Other top guests include Colleen Doran, Jill Thompson, and Afua Richardson. Doran, an Eisner, Harvey, and Internaonal Horror Guild Award-winning illustrator, is a New York Times bestselling arst for her work on Neil Gaiman’s graphic novel Troll Bridge and Stan Lee’s autobiography A mazing, Fantastic, Incredible Stan Lee. -

Comics As a Medium Dor Inquiry: Urban Students (Re-)Designing Critical Social Worlds

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Comics as a Medium dor Inquiry: Urban Students (Re-)Designing Critical Social Worlds David Eric Low University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Low, David Eric, "Comics as a Medium dor Inquiry: Urban Students (Re-)Designing Critical Social Worlds" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1090. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1090 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1090 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comics as a Medium dor Inquiry: Urban Students (Re-)Designing Critical Social Worlds Abstract Literacy scholars have argued that curricular remediation marginalizes the dynamic meaning-making practices of urban youth and ignores contemporary definitions of literacy as multimodal, socially situated, and tied to people's identities as members of cultural communities. For this reason, it is imperative that school-based literacy research unsettle status quos by foregrounding the sophisticated practices that urban students enact as a result, and in spite of, the marginalization they manage in educational settings. A hopeful site for honoring the knowledge of urban students is the nexus of alternative learning spaces that have taken on increased significance in ouths'y lives. Many of these spaces focus on young people's engagements with new literacies, multimodalities, the arts, and popular media, taking the stance that students' interests are inherently intellectual. The Cabrini Comics Inquiry Community (CCIC), located in a K-8 Catholic school in South Philadelphia, is one such space.