Extending and Visualizing Authorship in Comics Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

JKA918 Manga Studies (JB, VT2019) (1) Studying Manga: Introduction to the Research Field Inside and Outside of Japan JB (2007)

JKA918 Manga Studies (JB, VT2019) (1) Studying manga: Introduction to the research field inside and outside of Japan JB (2007), “Considering Manga Discourse: Location, Ambiguity, Historicity”. In Japanese Visual Culture, edited by Mark MacWilliams, pp. 351-369. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe [e-book]; JB (2016), Chapter 8 “Manga, which Manga? Publication Formats, Genres, Users,” in Japanese Civilization in the 21st Century. New York: Nova Science Publishers, ed. Andrew Targowski et al., pp. 121-133; Kacsuk, Zoltan (2018), “Re-Examining the ‘What is Manga’ Problematic: The Tension and Interrelationship between the ‘Style’ Versus ‘Made in Japan’ Positions,” Arts 7, 26; https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/7/3/26 (2) + (3) Archiving popular media: Museum, database, commons (incl. sympos. Archiving Anime) JB (2012), “Manga x Museum in Contemporary Japan,” Manhwa, Manga, Manhua: East Asian Comics Studies, Leipzig UP, pp. 141-150; Azuma, Hiroki ((2009), Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals, UP of Minnesota; ibid. (2012), “Database Animals,” in Ito, Mizuko, ed., Fandom Unbound: Otaku Culture in a Connected World, Yale UP, pp. 30–67. [e-book] (4) Manga as graphic narrative 1: Tezuka Osamu’s departure from the ‘picture story’ Pre- reading: ex. Shimada Keizō, “The Adventures of Dankichi,” in Reading Colonial Japan: Text, Context, and Critique, ed. Michele Mason & Helen Lee, Stanford UP, 2012, pp. 243-270. [e-book]; Natsume, Fusanosuke (2013). “Where Is Tezuka?: A Theory of Manga Expression,” Mechademia vol. 8, pp. 89-107 [e-journal]; [Clarke, M.J. (2017), “Fluidity of figure and space in Osamu Tezuka’s Ode to Kirihito,” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 26pp. -

Der Kree/Skrull-Krieg Thomas • Adams • Buscema ™

™ DER KREE/SKRULL-KRIEG THOMAS • ADAMS • BUSCEMA ™ DER KREE/SKRULL-KRIEG ____________________________________________________________________________NUR EIN TOTER ALIEN… 6 The Only Good Alien… Avengers (1963) 89 Juni 1971 ___________________________________________________________________________DAS JÜNGSTE GERICHT! 26 Judgment Day Avengers (1963) 90 Juli 1971 ___________________________________________________________________________EIN GROSSER SCHRITT FÜR DIE MENSCHHEIT… ZURÜCK! 46 Take One Giant Step-- Backward! Avengers (1963) 91 August 1971 ___________________________________________________________________________ALLES HAT EIN ENDE! 66 All Things Must End! Avengers (1963) 92 September 1971 ___________________________________________________________________________BRÜCKENKOPF ERDE 94 This Beachhead Earth Avengers (1963) 93 November 1971 __________________________________________________________________________INHUMANS UND ANDERE! 129 More than Inhuman! Avengers (1963) 94 Dezember 1971 __________________________________________________________________________EIN INHUMAN ERSCHEINT…! 153 Something Inhuman this Way Comes…! Avengers (1963) 95 Januar 1972 __________________________________________________________________________ANDROMEDA-NEBEL! 175 The Andromeda Swarm! Avengers (1963) 96 Februar 1972 __________________________________________________________________________DAS ENDE EINES GOTTES! 197 Godhood’s End! Avengers (1963) 97 März 1972 ™ DER KREE/SKRULL-KRIEG NEAL ADAMS NEAL ADAMS ROY THOMAS AUTOREN SAL BUSCEMA SAM GRAINGER NEAL -

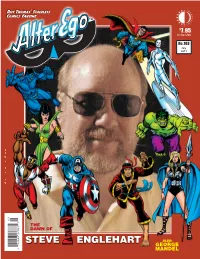

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

A Visual-Textual Analysis of Sarah Glidden's

BLACKOUTS MADE VISIBLE: A VISUAL-TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF SARAH GLIDDEN’S COMICS JOURNALISM _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial FulfillMent of the RequireMents for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by TYNAN STEWART Dr. Berkley Hudson, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have exaMined the thesis entitleD BLACKOUTS MADE VISIBLE: A VISUAL-TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF SARAH GLIDDEN’S COMICS JOURNALISM presented by Tynan Stewart, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. —————————————————————————— Dr. Berkley Hudson —————————————————————————— Dr. Cristina Mislán —————————————————————————— Dr. Ryan Thomas —————————————————————————— Dr. Kristin Schwain DEDICATION For my parents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My naMe is at the top of this thesis, but only because of the goodwill and generosity of many, many others. Some of those naMed here never saw a word of my research but were still vital to My broader journalistic education. My first thank you goes to my chair, Berkley Hudson, for his exceptional patience and gracious wisdom over the past year. Next, I extend an enormous thanks to my comMittee meMbers, Cristina Mislán, Kristin Schwain, and Ryan Thomas, for their insights and their tiMe. This thesis would be so much less without My comMittee’s efforts on my behalf. TiM Vos also deserves recognition here for helping Me narrow my initial aMbitions and set the direction this study would eventually take. The Missourian newsroom has been an all-consuming presence in my life for the past two and a half years. -

The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals By

Comics Aren’t Just For Fun Anymore: The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals by David Recine A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in TESOL _________________________________________ Adviser Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date University of Wisconsin-River Falls 2013 Comics, in the form of comic strips, comic books, and single panel cartoons are ubiquitous in classroom materials for teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL). While comics material is widely accepted as a teaching aid in TESOL, there is relatively little research into why comics are popular as a teaching instrument and how the effectiveness of comics can be maximized in TESOL. This thesis is designed to bridge the gap between conventional wisdom on the use of comics in ESL/EFL instruction and research related to visual aids in learning and language acquisition. The hidden science behind comics use in TESOL is examined to reveal the nature of comics, the psychological impact of the medium on learners, the qualities that make some comics more educational than others, and the most empirically sound ways to use comics in education. The definition of the comics medium itself is explored; characterizations of comics created by TESOL professionals, comic scholars, and psychologists are indexed and analyzed. This definition is followed by a look at the current role of comics in society at large, the teaching community in general, and TESOL specifically. From there, this paper explores the psycholinguistic concepts of construction of meaning and the language faculty. -

Massive Darkness Rulebook

RULES & QUESTS MASSIVE DARKNESS - RULES CHAPTERS GAME COMPONENTS ................... 3 ENEMIES’ PHASE........................ 28 Step 1 – Attack . 28 STORY: THE LIGHTBRINGERS’ LEGACY......... 5 Step 2 – Move . 28 SETUP ............................ 6 Step 3 – Attack . 28 Step 4 – Move . 28 GAME OVERVIEW ..................... 11 EXPERIENCE PHASE ....................... 31 BASIC RULES . 12 EVENT PHASE.......................... 32 ACTORS............................... 12 END PHASE ........................... 33 ZONES ............................... 13 COMBAT.......................... 33 SHADOW MODE.......................... 13 COMBAT ROLL ......................... 33 LINE OF SIGHT .......................... 14 Step 1 – Rolling Dice . 33 MOVING .............................. 15 Step 2 – Resolve The Enchantments . 34 LEVELS AND LEVEL TOKENS .................. 15 Step 3 – Inflict Pain! . 35 COMBAT DICE........................... 16 MOB RULES ........................... 36 HEROES ........................... 17 ADDITIONAL RULES ................... 37 HERO CARD ............................ 17 ARTIFACTS............................ 37 HERO DASHBOARD ........................ 17 OBJECTIVE AND PILLAR TOKENS .............. 37 CLASS SHEET ........................... 18 STUN ............................... 37 EQUIPMENT CARDS ................... 19 STORY MODE .......................... 38 COMBAT EQUIPMENT ...................... 19 Experience And Level . 38 Event Cards . 38 ITEMS .............................. 20 Inventory . 38 CONSUMABLES ........................ -

Spawn: Origins: Book 2 Free Ebook

FREESPAWN: ORIGINS: BOOK 2 EBOOK Todd McFarlane | 328 pages | 02 Nov 2010 | Image Comics | 9781607062288 | English | Fullerton, United States Spawn (comics) Spawn: Origins Collection, Book 2: Spawn #13–25 November 2, Spawn: Origins Collection, Book 3: Spawn #26–37 March 8, Spawn: Origins Collection, Book 4: Spawn #38–50 September 27, Spawn: Origins Collection, Book 5: Spawn #51–62 January 3, Spawn Origins Volume 2 includes classic Spawn stories written by Alan Moore and Frank Miller, as well as the introduction of memorable characters into the Spawn universe. Collects Spawn #7, 8, Spawn: Origins Volume 2 (Spawn Origins Collections) Paperback – Illustrated, November 15, by Todd McFarlane (Author, Artist) out of 5 stars ratings. PDF Download Spawn: Origins Volume 2 (Spawn Origins Collections) Paperback – Illustrated, November 15, by Todd McFarlane (Author, Artist) out of 5 stars ratings. The SPAWN: ORIGINS BOOK TWO HC includes classic Spawn stories written by TODD McFARLANE, as well as industry giants GRANT MORRISON, TOM ORZECHOWSKI and ANDREW GROSSBERG. Revisit epic battles that. Spawn Origins Volume 2 includes classic Spawn stories written by Alan Moore and Frank Miller, as well as the introduction of memorable characters into the Spawn universe. Product Details ISBN Spawn: Origins Book 2 Spawn Origins Volume 2 includes classic Spawn stories written by Alan Moore and Frank Miller, as well as the introduction of memorable characters into the Spawn universe. Product Details ISBN Spawn: Origins Collection, Book 2: Spawn #13–25 November 2, Spawn: Origins Collection, Book 3: Spawn #26–37 March 8, Spawn: Origins Collection, Book 4: Spawn #38–50 September 27, Spawn: Origins Collection, Book 5: Spawn #51–62 January 3, The SPAWN: ORIGINS BOOK TWO HC includes classic Spawn stories written by TODD McFARLANE, as well as industry giants GRANT MORRISON, TOM ORZECHOWSKI and ANDREW GROSSBERG. -

Doing Social Sciences Via Comics and Graphic Novels. an Introduction

Re-formats: Envisioning Sociology – peer-reviewed Sociologica. V.15 N.1 (2021) https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/12773 ISSN 1971-8853 Doing Social Sciences Via Comics and Graphic Novels. An Introduction Eduardo Barberis* a Barbara Grüning b a Department of Economics, Society, Politics, University of Urbino Carlo Bo (Italy) b Department of Sociology and Social Research, University of Milan-Bicocca (Italy) Submitted: March 16, 2021 – Revised version: April 25, 2021 Accepted: May 8, 2021 – Published: May 26, 2021 Abstract Visual communication is far from new and is almost as old as the social sciences. In the last decades, the interest in the visual dimension of society as well as towards the visual as expression of local and global cultures increased to the extent that specific disciplinary approaches took root — e.g. visual anthropology and visual sociology. Nevertheless, it seems to us that whereas they are mostly engaged in collecting visual data and analyzing visual cultural products, little attention is paid to one of the original uses of visual mate- rial in ethnographic and social research, that is communicating social sciences. Depart- ing from some general questions, such as how visualizing sociological concepts, what role non-textual stimuli play in sociology, how they differentiate according to the kind of pub- lic, and how we can critically and reflexively assess the social and disciplinary implications of visualizations of empirical research, we collect in the special issues contributions from social scientists and comics artists who materially engaged in the production of social sci- ences via comics and graphic narratives. The article is divided into three parts. -

Customer Order Form

#355 | APR18 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE APR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Apr18 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:51:03 PM You'll for PREVIEWS!PREVIEWS! STARTING THIS MONTH Toys & Merchandise sections start with the Back Cover! Page M-1 Dynamite Entertainment added to our Premier Comics! Page 251 BOOM! Studios added to our Premier Comics! Page 279 New Manga section! Page 471 Updated Look & Design! Apr18 Previews Flip Ad.indd 1 3/8/2018 9:55:59 AM BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SWORD SLAYER SEASON 12: DAUGHTER #1 THE RECKONING #1 DARK HORSE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS THE MAN OF JUSTICE LEAGUE #1 THE LEAGUE OF STEEL #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT EXTRAORDINARY DC ENTERTAINMENT GENTLEMEN: THE TEMPEST #1 IDW ENTERTAINMENT THE MAGIC ORDER #1 IMAGE COMICS THE WEATHERMAN #1 IMAGE COMICS CHARLIE’S ANT-MAN & ANGELS #1 BY NIGHT #1 THE WASP #1 DYNAMITE BOOM! STUDIOS MARVEL COMICS ENTERTAINMENT Apr18 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:39:16 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT InSexts Year One HC l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Lost City Explorers #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Carson of Venus: Fear on Four Worlds #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Archie’s Super Teens vs. Crusaders #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Solo: A Star Wars Story: The Official Guide HC l DK PUBLISHING CO The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide Volume 48 SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Mae Volume 1 TP l LION FORGE 1 A Tale of a Thousand and One Nights: Hasib & The Queen of Serpents HC l NBM Shadow Roads #1 l ONI PRESS INC. -

Transatlantica, 1 | 2010 “How ‘Ya Gonna Keep’Em Down at the Farm Now That They’Ve Seen Paree?”: France

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 1 | 2010 American Shakespeare / Comic Books “How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France in Super Hero Comics Nicolas Labarre Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/4943 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.4943 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher Association française d'Etudes Américaines (AFEA) Electronic reference Nicolas Labarre, ““How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France in Super Hero Comics”, Transatlantica [Online], 1 | 2010, Online since 02 September 2010, connection on 22 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/4943 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/transatlantica.4943 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. “How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France... 1 “How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France in Super Hero Comics Nicolas Labarre 1 Super hero comics are a North-American narrative form. Although their ascendency points towards European ancestors, and although non-American heroes have been sharing their characteristics for a long time, among them Obelix, Diabolik and many manga characters, the cape and costume genre remains firmly grounded in the United States. It is thus unsurprising that, with a brief exception during the Second World War, super hero narratives should have taken place mostly in the United States (although Metropolis, Superman’s headquarter, was notoriously based on Toronto) or in outer space. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism.