Demon Girl Power: Regimes of Form and Force in Videogames Primal and Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Massive Darkness Rulebook

RULES & QUESTS MASSIVE DARKNESS - RULES CHAPTERS GAME COMPONENTS ................... 3 ENEMIES’ PHASE........................ 28 Step 1 – Attack . 28 STORY: THE LIGHTBRINGERS’ LEGACY......... 5 Step 2 – Move . 28 SETUP ............................ 6 Step 3 – Attack . 28 Step 4 – Move . 28 GAME OVERVIEW ..................... 11 EXPERIENCE PHASE ....................... 31 BASIC RULES . 12 EVENT PHASE.......................... 32 ACTORS............................... 12 END PHASE ........................... 33 ZONES ............................... 13 COMBAT.......................... 33 SHADOW MODE.......................... 13 COMBAT ROLL ......................... 33 LINE OF SIGHT .......................... 14 Step 1 – Rolling Dice . 33 MOVING .............................. 15 Step 2 – Resolve The Enchantments . 34 LEVELS AND LEVEL TOKENS .................. 15 Step 3 – Inflict Pain! . 35 COMBAT DICE........................... 16 MOB RULES ........................... 36 HEROES ........................... 17 ADDITIONAL RULES ................... 37 HERO CARD ............................ 17 ARTIFACTS............................ 37 HERO DASHBOARD ........................ 17 OBJECTIVE AND PILLAR TOKENS .............. 37 CLASS SHEET ........................... 18 STUN ............................... 37 EQUIPMENT CARDS ................... 19 STORY MODE .......................... 38 COMBAT EQUIPMENT ...................... 19 Experience And Level . 38 Event Cards . 38 ITEMS .............................. 20 Inventory . 38 CONSUMABLES ........................ -

The Terminator by John Wills

The Terminator By John Wills “The Terminator” is a cult time-travel story pitting hu- mans against machines. Authored and directed by James Cameron, the movie features Arnold Schwarzenegger, Linda Hamilton and Michael Biehn in leading roles. It launched Cameron as a major film di- rector, and, along with “Conan the Barbarian” (1982), established Schwarzenegger as a box office star. James Cameron directed his first movie “Xenogenesis” in 1978. A 12-minute long, $20,000 picture, “Xenogenesis” depicted a young man and woman trapped in a spaceship dominated by power- ful and hostile robots. It introduced what would be- come enduring Cameron themes: space exploration, machine sentience and epic scale. In the early 1980s, Cameron worked with Roger Corman on a number of film projects, assisting with special effects and the design of sets, before directing “Piranha II” (1981) as his debut feature. Cameron then turned to writing a science fiction movie script based around a cyborg from 2029AD travelling through time to con- Artwork from the cover of the film’s DVD release by MGM temporary Los Angeles to kill a waitress whose as Home Entertainment. The Library of Congress Collection. yet unborn son is destined to lead a resistance movement against a future cyborg army. With the input of friend Bill Wisher along with producer Gale weeks. However, critical reception hinted at longer- Anne Hurd (Hurd and Cameron had both worked for lasting appeal. “Variety” enthused over the picture: Roger Corman), Cameron finished a draft script in “a blazing, cinematic comic book, full of virtuoso May 1982. After some trouble finding industry back- moviemaking, terrific momentum, solid performances ers, Orion agreed to distribute the picture with and a compelling story.” Janet Maslin for the “New Hemdale Pictures financing it. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Extending and Visualizing Authorship in Comics Studies

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Nicholas A. Brown for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on April 30, 2015 Title: Extending and Visualizing Authorship in Comics Studies. Abstract approved: ________________________________________________________________________ Tim T. Jensen Ehren H. Pflugfelder This thesis complicates the traditional associations between authorship and alphabetic composition within the comics medium and examines how the contributions of line artists and writers differ and may alter an audience's perceptions of the medium. As a fundamentally multimodal and collaborative work, the popular superhero comic muddies authorial claims and requires further investigations should we desire to describe authorship more accurately and equitably. How might our recognition of the visual author alter our understandings of the author construct within, and beyond, comics? In this pursuit, I argue that the terminology available to us determines how deeply we may understand a topic and examine instances in which scholars have attempted to develop on a discipline's body of terminology by borrowing from another. Although helpful at first, these efforts produce limited success, and discipline-specific terms become more necessary. To this end, I present the visual/alphabetic author distinction to recognize the possibility of authorial intent through the visual mode. This split explicitly recognizes the possibility of multimodal and collaborative authorships and forces us to re-examine our beliefs about authorship more generally. Examining the editors' note, an instance of visual plagiarism, and the MLA citation for graphic narratives, I argue for recognition of alternative authorships in comics and forecast how our understandings may change based on the visual/alphabetic split. -

Women in Film Time: Forty Years of the Alien Series (1979–2019)

IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 6 – Issue 2 – Autumn 2019 Women in Film Time: Forty Years of the Alien Series (1979–2019) Susan George, University of Delhi, India. Abstract Cultural theorists have had much to read into the Alien science fiction film series, with assessments that commonly focus on a central female ‘heroine,’ cast in narratives that hinge on themes of motherhood, female monstrosity, birth/death metaphors, empire, colony, capitalism, and so on. The films’ overarching concerns with the paradoxes of nature, culture, body and external materiality, lead us to concur with Stephen Mulhall’s conclusion that these concerns revolve around the issue of “the relation of human identity to embodiment”. This paper uses these cultural readings as an entry point for a tangential study of the Alien films centring on the subject of time. Spanning the entire series of four original films and two recent prequels, this essay questions whether the Alien series makes that cerebral effort to investigate the operations of “the feminine” through the space of horror/adventure/science fiction, and whether the films also produce any deliberate comment on either the lived experience of women’s time in these genres, or of film time in these genres as perceived by the female viewer. Keywords: Alien, SF, time, feminine, film 59 IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 6 – Issue 2 – Autumn 2019 Alien Films that Philosophise Ridley Scott’s 1979 S/F-horror film Alien spawned not only a remarkable forty-year cinema obsession that has resulted in six specific franchise sequels and prequels till date, but also a considerable amount of scholarly interest around the series. -

From Synthespian to Convergence Character: Reframing the Digital Human in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema by Jessica L. Aldred

From Synthespian to Convergence Character: Reframing the Digital Human in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema by Jessica L. Aldred A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2012 Jessica L. Aldred Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94206-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94206-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

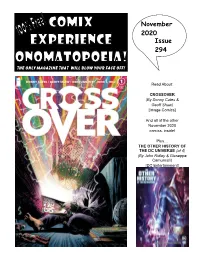

Issue 294 November 2020

November 2020 Issue 294 The only magazine that will blow your face off! Read About: CROSSOVER (By Donny Cates & Geoff Shaw) [Image Comics] And all of the other November 2020 comics, inside! Plus… THE OTHER HISTORY OF THE DC UNIVERSE (of 4) (By John Ridley & Giuseppe Camuncoli) [DC Entertainment] Welcome back my friends, to the show deposit of $5.00 or 50% of the value of and delivering to us the subscription form, that never ends. Before we have the your order, whichever is greater. Please you agree to pay for and pick up all books judges come out and explain the rules, note that this deposit will be applied to any ordered. By signing the deposit form and we'd like to open with a statement about outstanding amounts you owe us for paying us the deposit, you agree to allow comic books in general. If you use it as a books that you have not picked up within us to use the deposit to cover the price of guideline, you'll never be unhappy... the required time. If the deposit amount is any books you do not pick up! not sufficient, we may require you to pay ONLY BUY COMICS THAT YOU the balance due before accepting any We only have a limited amount of room READ AND ENJOY! other subscription form requests. on the sub form , however we will happily order any item out of the distributor’s We cannot stress that highly enough. 3. If you mark it, you buy it. We base our catalog that you desire. -

Considering the Female Hero in Speculative Fiction

University of Pretoria etd – Donaldson, E (2003) The Amazon goes nova: considering the female hero in speculative fiction by Eileen Donaldson submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Magister Artium (English) in the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Pretoria December 2003 Supervisor: Ms Molly Brown 1 University of Pretoria etd – Donaldson, E (2003) Acknowledgements Ms Molly Brown for her unfailing tact, guidance, support and encouragement. Dedication To my grandfather who loves all ‘dishevelled wandering stars,’ And has shared that love with all of us, To my grandmother for countless ‘Once upon a times,’ And to my mother and father who saw a UFO in the harvest of 1978. 2 University of Pretoria etd – Donaldson, E (2003) Summary The female hero has been marginalized through history, to the extent that theorists, from Plato and Aristotle to those of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, state that a female hero is impossible. This thesis argues that she is not impossible. Concentrating on the work of Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell, a heroic standard is proposed against which to measure both male and female heroes. This heroic standard suggests that a hero must be human, must act, must champion a heroic ethic and must undertake a quest. Should a person, male or female, comply with these criteria, that person can be considered a hero. This thesis refutes the patriarchal argument against female heroism, proposing that the argument is faulty because it has at its base a constricting male-constructed myth of femininity. This myth suggests that women are naturally docile and passive, not given to aggression and heroism, but rather to motherhood and adaptation to adverse circumstances, it does not reflect the reality of women’s natural abilities or capacity for action. -

SEP 2010 Order Form PREVIEWS#264 MARVEL COMICS

Sep10 COF C1:COF C1.qxd 8/11/2010 12:22 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 11 SEP 2010 SEP E COMIC H T SHOP’S CATALOG COF C2:Layout 1 8/6/2010 1:36 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page Sept:gem page v18n1.qxd 8/12/2010 8:55 AM Page 1 KULL: THE HATE WITCH #1 (OF 4) BATMAN: DARK HORSE COMICS THE DARK KNIGHT #1 DC COMICS HELLBOY: DOUBLE FEATURE OF EVIL DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN, INC. #1 THE WALKING DEAD DC COMICS VOL. 13: TOO FAR GONE TP IMAGE COMICS MAGAZINE GEM OF THE MONTH DUNGEONS & DRAGONS #1 IDW PUBLISHING ..UTOPIAN #1 IMAGE COMICS WIZARD #232 WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT GENERATION HOPE #1 MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 8/12/2010 2:47 PM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS ELMER GN G AMAZE INK/SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS NIGHTMARES & FAIRY TALES: ANNABELLE‘S STORY #1 G AMAZE INK/SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS S.E. HINTON‘S PUPPY SISTER GN G BLUEWATER PRODUCTIONS STAN LEE‘S TRAVELER #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 1 DARKWING DUCK VOLUME 1: THE DUCK KNIGHT RETURNS TP G BOOM! STUDIOS LADY DEATH ORIGINS VOLUME 1 TP/HC G BOUNDLESS COMICS VAMPIRELLA #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT KEVIN SMITH‘S GREEN HORNET VOLUME 1: SINS OF THE FATHER TP G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT ACME NOVELTY LIBRARY VOLUME 20 HC G DRAWN & QUARTERLY NORTH GUARD #1 G MOONSTONE LAST DAYS OF AMERICAN CRIME TP G RADICAL PUBLISHING ATOMIC ROBO AND THE DEADLY ART OF SCIENCE #1 G RED 5 COMICS BOOKS & MAGAZINES COMICS SHOP SC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES KRAZY KAT AND THE ART OF GEORGE HERRIMAN HC G COMICS SPYDA CREATIONS: STUDY OF THE SCULPTURAL METHOD SC G HOW-TO 2 STAR TREK: USS ENTERPRISE HAYNES OWNER‘S MANUAL HC G STAR -

The “Tron: Legacy”

Release Date: December 16 Rating: TBC Run time: TBC rom Walt Disney Pictures comes “TRON: Legacy,” a high-tech adventure set in a digital world that is unlike anything ever captured on the big screen. Directed by F Joseph Kosinski, “TRON: Legacy” stars Jeff Bridges, Garrett Hedlund, Olivia Wilde, Bruce Boxleitner, James Frain, Beau Garrett and Michael Sheen and is produced by Sean Bailey, Jeffrey Silver and Steven Lisberger, with Donald Kushner serving as executive producer, and Justin Springer and Steve Gaub co-producing. The “TRON: Legacy” screenplay was written by Edward Kitsis and Adam Horowitz; story by Edward Kitsis & Adam Horowitz and Brian Klugman & Lee Sternthal; based on characters created by Steven Lisberger and Bonnie MacBird. Presented in Disney Digital 3D™, Real D 3D and IMAX® 3D and scored by Grammy® Award–winning electronic music duo Daft Punk, “TRON: Legacy” features cutting-edge, state-of-the-art technology, effects and set design that bring to life an epic adventure coursing across a digital grid that is as fascinating and wondrous as it is beyond imagination. At the epicenter of the adventure is a father-son story that resonates as much on the Grid as it does in the real world: Sam Flynn (Garrett Hedlund), a rebellious 27-year-old, is haunted by the mysterious disappearance of his father, Kevin Flynn (Oscar® and Golden Globe® winner Jeff Bridges), a man once known as the world’s leading tech visionary. When Sam investigates a strange signal sent from the old Flynn’s Arcade—a signal that could only come from his father—he finds himself pulled into a digital grid where Kevin has been trapped for 20 years. -

Publication Review Report Thru 06-10-19 Selection: Complex Disposition: Excluded, Complex Disposition: Excluded

Publication Review Report thru 06-10-19 Selection: Complex Disposition: Excluded, Complex Disposition: Excluded, Publication Title Publisher Publication Publication Publication Publication Publication Complex Complex OPR OPR Type Date Volume Number ISBN Disposition Disposition Disposition Disposition Date Date Adult Cinema Review 37653 Excluded Excluded 3/3/2004 Adult DVD Empire.com ADE0901 Excluded Excluded 3/23/2009 Adventures From the Technology 2006 ISBN: 1-4000- Excluded Excluded 9/10/2010 Underground 5082-0 Aftermath, Inc. – Cleaning Up After 2007 978-1-592-40364-6 Excluded Excluded 7/15/2011 CSI Goes Home AG Super Erotic Manga Anthology 39448 Excluded Excluded 3/5/2009 Against Her Will 1995 ISBN: 0-7860- Excluded Excluded 3/11/2011 1388-5 Ages of Gold & Silver by John G. 1990 0-910309-6 Excluded Excluded 11/16/2009 Jackson Aikido Complete 1969 ISBN 0-8065- Excluded Excluded 2/10/2006 0417-X Air Conditioning and Refrigeration 2006 ISBN: 0-07- Excluded Excluded 6/10/2010 146788-2 AL Qaeda - Brotherhood of Terror 2002 ISBN: 0-02- Excluded Excluded 3/10/2008 864352-6 Alberto 1979 V12 Excluded Excluded 8/6/2010 Algiers Tomorrow 1993 1-56201-211-8 Excluded Excluded 6/30/2011 All Flesh Must be Eaten, Revised 2009 1-891153-31-5 Excluded Excluded 6/3/2011 Edition All In - The World's Leading Poker 39083 Excluded Excluded 12/7/2006 Magazine All the Best Rubbish – The Classic 2009 978-0-06-180989-7 Excluded Excluded 8/19/2011 Ode to Collecting All The Way 38808 V20/N4 Excluded Excluded 2 September/Oct Excluded Excluded 9/15/2005 ober 2002 101 Things Every Man Should 2008 ISBN: 978-1- Excluded Excluded 5/6/2011 Know How to Do 935003-04-5 101 Things You Should Know How 2005 978-1-4024-6308-3 Excluded Excluded 5/15/2009 To Do 18 Year Old Baby Girl, The.txt Excluded Excluded 1/8/2010 2,286 Traditional Stencil Designs by 1991 IBSN 0-486- Excluded Excluded 1/6/2009 H. -

Fiscal Year 2015 Annual Financial Report and Shareholder Letter 10DEC201511292957

6JAN201605190975 Fiscal Year 2015 Annual Financial Report And Shareholder Letter 10DEC201511292957 10DEC201400361461 Dear Shareholders, The Force was definitely with us this year! Fiscal 2015 was another triumph across the board in terms of creativity and innovation as well as financial performance. For the fifth year in a row, The Walt Disney Company delivered record results with revenue, net income and earnings per share all reaching historic highs once again. It’s an impressive winning streak that speaks to our continued leadership in the entertainment industry, the incredible demand for our brands and franchises, and the special place our storytelling has in the hearts and lives of millions of people around the world. All of which is even more remarkable when you remember that Disney first started entertaining audiences almost a century ago. The world certainly looks a lot different than it did when Walt Disney first opened shop in 1923, and so does the company that bears his name. Our company continues to evolve with each generation, mixing beloved characters and storytelling traditions with grand new experiences that are relevant to our growing global audience. Even though we’ve been telling our timeless stories for generations, Disney maintains the bold, ambitious heart of a company just getting started in a world full of promise. And it’s getting stronger through strategic acquisitions like Pixar, Marvel and Lucasfilm that continue to bring new creative energy across the company as well as the constructive disruptions of this dynamic digital age that unlock new opportunities for growth. Our willingness to challenge the status quo and embrace change is one of our greatest strengths, especially in a media market rapidly transforming with each new technology or consumer trend.