Considering the Female Hero in Speculative Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Massive Darkness Rulebook

RULES & QUESTS MASSIVE DARKNESS - RULES CHAPTERS GAME COMPONENTS ................... 3 ENEMIES’ PHASE........................ 28 Step 1 – Attack . 28 STORY: THE LIGHTBRINGERS’ LEGACY......... 5 Step 2 – Move . 28 SETUP ............................ 6 Step 3 – Attack . 28 Step 4 – Move . 28 GAME OVERVIEW ..................... 11 EXPERIENCE PHASE ....................... 31 BASIC RULES . 12 EVENT PHASE.......................... 32 ACTORS............................... 12 END PHASE ........................... 33 ZONES ............................... 13 COMBAT.......................... 33 SHADOW MODE.......................... 13 COMBAT ROLL ......................... 33 LINE OF SIGHT .......................... 14 Step 1 – Rolling Dice . 33 MOVING .............................. 15 Step 2 – Resolve The Enchantments . 34 LEVELS AND LEVEL TOKENS .................. 15 Step 3 – Inflict Pain! . 35 COMBAT DICE........................... 16 MOB RULES ........................... 36 HEROES ........................... 17 ADDITIONAL RULES ................... 37 HERO CARD ............................ 17 ARTIFACTS............................ 37 HERO DASHBOARD ........................ 17 OBJECTIVE AND PILLAR TOKENS .............. 37 CLASS SHEET ........................... 18 STUN ............................... 37 EQUIPMENT CARDS ................... 19 STORY MODE .......................... 38 COMBAT EQUIPMENT ...................... 19 Experience And Level . 38 Event Cards . 38 ITEMS .............................. 20 Inventory . 38 CONSUMABLES ........................ -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Extending and Visualizing Authorship in Comics Studies

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Nicholas A. Brown for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on April 30, 2015 Title: Extending and Visualizing Authorship in Comics Studies. Abstract approved: ________________________________________________________________________ Tim T. Jensen Ehren H. Pflugfelder This thesis complicates the traditional associations between authorship and alphabetic composition within the comics medium and examines how the contributions of line artists and writers differ and may alter an audience's perceptions of the medium. As a fundamentally multimodal and collaborative work, the popular superhero comic muddies authorial claims and requires further investigations should we desire to describe authorship more accurately and equitably. How might our recognition of the visual author alter our understandings of the author construct within, and beyond, comics? In this pursuit, I argue that the terminology available to us determines how deeply we may understand a topic and examine instances in which scholars have attempted to develop on a discipline's body of terminology by borrowing from another. Although helpful at first, these efforts produce limited success, and discipline-specific terms become more necessary. To this end, I present the visual/alphabetic author distinction to recognize the possibility of authorial intent through the visual mode. This split explicitly recognizes the possibility of multimodal and collaborative authorships and forces us to re-examine our beliefs about authorship more generally. Examining the editors' note, an instance of visual plagiarism, and the MLA citation for graphic narratives, I argue for recognition of alternative authorships in comics and forecast how our understandings may change based on the visual/alphabetic split. -

Demon Girl Power: Regimes of Form and Force in Videogames Primal and Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Demon Girl Power: Regimes of Form and Force in videogames Primal and Buffy the Vampire Slayer Tanya Krzywinska Brunel University Abstract 'There's nothing like a spot of demon slaughter to make a girl's night' Since the phenomenal success of the Tomb Raider (1996) videogame series a range of other videogames have used carefully branded animated female avatars. As with most other media, the game industry tends to follow and expand on established lucrative formats to secure an established market share. Given the capacity of videogames to create imaginary worlds in 3D that can be interacted with, it is not perhaps surprising that pre-established worlds are common in videogames, as is the case with Buffy the Vampire Slayer (there are currently three videogames based on the cult TV show 2000-2003), but in other games worlds have to be built from scratch, as is the case with Primal (2003). With the mainstream media's current romance with kick- ass action heroines, the advantage of female animated game avatars is their potential to broaden the appeal of games across genders. This is however a double-edged affair: as well as appealing to what might be a termed a post-feminist market, animated forms enable hyper-feminine proportions and impossible vigour. I argue that becoming demon - afforded by the plasticity of animation –- in these games troubles the representational qualities ordinarily afforded to female avatars in videogames. But I also argue that theories of representation are insufficient for a full understanding of the formal particularities of videogames and as such it is crucial to address the impact of media-specific attributes of videogames on the interpellation of players into the game space and the way that power regimes are organised. -

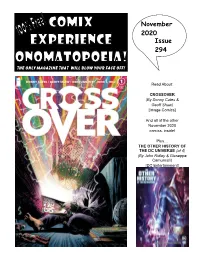

Issue 294 November 2020

November 2020 Issue 294 The only magazine that will blow your face off! Read About: CROSSOVER (By Donny Cates & Geoff Shaw) [Image Comics] And all of the other November 2020 comics, inside! Plus… THE OTHER HISTORY OF THE DC UNIVERSE (of 4) (By John Ridley & Giuseppe Camuncoli) [DC Entertainment] Welcome back my friends, to the show deposit of $5.00 or 50% of the value of and delivering to us the subscription form, that never ends. Before we have the your order, whichever is greater. Please you agree to pay for and pick up all books judges come out and explain the rules, note that this deposit will be applied to any ordered. By signing the deposit form and we'd like to open with a statement about outstanding amounts you owe us for paying us the deposit, you agree to allow comic books in general. If you use it as a books that you have not picked up within us to use the deposit to cover the price of guideline, you'll never be unhappy... the required time. If the deposit amount is any books you do not pick up! not sufficient, we may require you to pay ONLY BUY COMICS THAT YOU the balance due before accepting any We only have a limited amount of room READ AND ENJOY! other subscription form requests. on the sub form , however we will happily order any item out of the distributor’s We cannot stress that highly enough. 3. If you mark it, you buy it. We base our catalog that you desire. -

SEP 2010 Order Form PREVIEWS#264 MARVEL COMICS

Sep10 COF C1:COF C1.qxd 8/11/2010 12:22 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 11 SEP 2010 SEP E COMIC H T SHOP’S CATALOG COF C2:Layout 1 8/6/2010 1:36 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page Sept:gem page v18n1.qxd 8/12/2010 8:55 AM Page 1 KULL: THE HATE WITCH #1 (OF 4) BATMAN: DARK HORSE COMICS THE DARK KNIGHT #1 DC COMICS HELLBOY: DOUBLE FEATURE OF EVIL DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN, INC. #1 THE WALKING DEAD DC COMICS VOL. 13: TOO FAR GONE TP IMAGE COMICS MAGAZINE GEM OF THE MONTH DUNGEONS & DRAGONS #1 IDW PUBLISHING ..UTOPIAN #1 IMAGE COMICS WIZARD #232 WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT GENERATION HOPE #1 MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 8/12/2010 2:47 PM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS ELMER GN G AMAZE INK/SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS NIGHTMARES & FAIRY TALES: ANNABELLE‘S STORY #1 G AMAZE INK/SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS S.E. HINTON‘S PUPPY SISTER GN G BLUEWATER PRODUCTIONS STAN LEE‘S TRAVELER #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 1 DARKWING DUCK VOLUME 1: THE DUCK KNIGHT RETURNS TP G BOOM! STUDIOS LADY DEATH ORIGINS VOLUME 1 TP/HC G BOUNDLESS COMICS VAMPIRELLA #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT KEVIN SMITH‘S GREEN HORNET VOLUME 1: SINS OF THE FATHER TP G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT ACME NOVELTY LIBRARY VOLUME 20 HC G DRAWN & QUARTERLY NORTH GUARD #1 G MOONSTONE LAST DAYS OF AMERICAN CRIME TP G RADICAL PUBLISHING ATOMIC ROBO AND THE DEADLY ART OF SCIENCE #1 G RED 5 COMICS BOOKS & MAGAZINES COMICS SHOP SC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES KRAZY KAT AND THE ART OF GEORGE HERRIMAN HC G COMICS SPYDA CREATIONS: STUDY OF THE SCULPTURAL METHOD SC G HOW-TO 2 STAR TREK: USS ENTERPRISE HAYNES OWNER‘S MANUAL HC G STAR -

Publication Review Report Thru 06-10-19 Selection: Complex Disposition: Excluded, Complex Disposition: Excluded

Publication Review Report thru 06-10-19 Selection: Complex Disposition: Excluded, Complex Disposition: Excluded, Publication Title Publisher Publication Publication Publication Publication Publication Complex Complex OPR OPR Type Date Volume Number ISBN Disposition Disposition Disposition Disposition Date Date Adult Cinema Review 37653 Excluded Excluded 3/3/2004 Adult DVD Empire.com ADE0901 Excluded Excluded 3/23/2009 Adventures From the Technology 2006 ISBN: 1-4000- Excluded Excluded 9/10/2010 Underground 5082-0 Aftermath, Inc. – Cleaning Up After 2007 978-1-592-40364-6 Excluded Excluded 7/15/2011 CSI Goes Home AG Super Erotic Manga Anthology 39448 Excluded Excluded 3/5/2009 Against Her Will 1995 ISBN: 0-7860- Excluded Excluded 3/11/2011 1388-5 Ages of Gold & Silver by John G. 1990 0-910309-6 Excluded Excluded 11/16/2009 Jackson Aikido Complete 1969 ISBN 0-8065- Excluded Excluded 2/10/2006 0417-X Air Conditioning and Refrigeration 2006 ISBN: 0-07- Excluded Excluded 6/10/2010 146788-2 AL Qaeda - Brotherhood of Terror 2002 ISBN: 0-02- Excluded Excluded 3/10/2008 864352-6 Alberto 1979 V12 Excluded Excluded 8/6/2010 Algiers Tomorrow 1993 1-56201-211-8 Excluded Excluded 6/30/2011 All Flesh Must be Eaten, Revised 2009 1-891153-31-5 Excluded Excluded 6/3/2011 Edition All In - The World's Leading Poker 39083 Excluded Excluded 12/7/2006 Magazine All the Best Rubbish – The Classic 2009 978-0-06-180989-7 Excluded Excluded 8/19/2011 Ode to Collecting All The Way 38808 V20/N4 Excluded Excluded 2 September/Oct Excluded Excluded 9/15/2005 ober 2002 101 Things Every Man Should 2008 ISBN: 978-1- Excluded Excluded 5/6/2011 Know How to Do 935003-04-5 101 Things You Should Know How 2005 978-1-4024-6308-3 Excluded Excluded 5/15/2009 To Do 18 Year Old Baby Girl, The.txt Excluded Excluded 1/8/2010 2,286 Traditional Stencil Designs by 1991 IBSN 0-486- Excluded Excluded 1/6/2009 H. -

Military Nanotechnology and Comic Books

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Nanowarriors: Military Nanotechnology and Comic Books Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7g44941c Journal Intertexts, 9(1) Author Milburn, Colin Publication Date 2005 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Intertexts 9.1 Pages final 3/15/06 3:22 PM Page 77 Nanowarriors: Military Nanotechnology and Comic Books Colin Milburn U N I V E R S I T Y O F C A L I F O R N I A , D AV I S In February 2002, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology submitted a proposal to the U.S. Army for a new research center devoted to developing military equipment enhanced with nanotechnology. The Army Research Office had issued broad agency solicitations for such a center in October 2001, and they enthusiastically selected MIT’s proposal from among several candidates, awarding them $50 million to kick start what became dubbed the MIT Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies (ISN). MIT’s proposal out- lined areas of nanoscience, polymer chemistry, and molecular engineering that could provide fruitful military applications in the near term, as well as more speculative applications in the future. It also featured the striking image of a mechanically armored woman warrior, standing amidst the mon- uments of some futuristic cityscape, packing two enormous guns and other assault devices (Figure 1). This image proved appealing enough beyond the proposal to grace the ISN’s earliest websites, and it also accompanied several publicity announcements for the institute’s inauguration. Figure 1: ISN Soldier of the Future. -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

A Scriptural Essay Towards the Proof of an Immortal Spirit In

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com --------- SCRIPTURAL ESSAY TOWARDS THE PROOF *OF AN IMMORTAL SPIRIT IN MAN; Bºein G. A ‘C O N T IN U A T H G N of the ~ F E M A R K 3 on Pr. PRI estley's Syſtem of MATER HAL is M. SECOND EDITION. -seeeeyeeee By Joseph BENSON. -Gºt Oen Te do err, not knowing the Scripturer. Ye ſuppoſe a doćtrine is not in them, becauſe ye have not found it in them. Becauſe ye have ſhut your own eyes ye vainly imagine there is no light in the Sun, and take upon you to affirm it. Not knowing the power of God, you call that impoſſible which you cannot do, deem that abſurd which you do not comprehend, and pronounce that falſe which you wiſh to be ſo. Hen. - Hunter, D. D. -sekee LONDON : Printed at the Conference-Qffice, North-Green, Finſbury-Square; Gro. Srory, Agent : Sold % R. LoMAs, at the New-Chapel, City-Road, and at the Methodiſt-Preaching-Houſes in Town and Country. 1805, --- Price Eight-pence, ( iš ) *r-resºººººººººººyeºn THE PREFACE. ****** Tº: ſubſtance of the following little tract was delivered in a ſermon preached at Hull, from Eccles. xii. 7. The Author had preached the pre ceding evening from the firſt verſe of the Chapter, on the occaſion of the death of a young perſon who was ſuddenly ſnatched away in the flower of youth, at a time when ſhe was attending the dying bed, and daily expecting the diſſolution of a tender mother. -

Paper XI: the 20Th Century Unit I Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness

1 Paper XI: The 20th Century Unit I Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness 1. Background 2. Plot Overview 3. Summary and Analysis 4. Character Analysis 5. Stylistic Devices of the Novel 6. Study Questions 7. Suggested Essay Topics 8. Suggestions for Further Reading 9. Bibliography Structure 1. Background 1.1 Introduction to the Author Joseph Conrad, one of the English language's greatest stylists, was born Teodor Josef Konrad Nalecz Korzenikowski in Podolia, a province of the Polish Ukraine. Poland had been a Roman Catholic kingdom since 1024, but was invaded, partitioned, and repartitioned throughout the late eighteenth-century by Russia, Prussia, and Austria. At the time of Conrad's birth (December 3, 1857), Poland was one-third of its size before being divided between the three great powers; despite the efforts of nationalists such as Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who led an unsuccessful uprising 2 in 1795, Poland was controlled by other nations and struggled for independence. When Conrad was born, Russia effectively controlled Poland. Conrad's childhood was largely affected by his homeland's struggle for independence. His father, Apollo Korzeniowski, belonged to the szlachta, a hereditary social class comprised of members of the landed gentry; he despised the Russian oppression of his native land. At the time of Conrad's birth, Apollo's land had been seized by the Russian government because of his participation in past uprisings. He and one of Conrad's maternal uncles, Stefan Bobrowski, helped plan an uprising against Russian rule in 1863. Other members of Conrad's family showed similar patriotic convictions: Kazimirez Bobrowski, another maternal uncle, resigned his commission in the army (controlled by Russia) and was imprisoned, while Robert and Hilary Korzeniowski, two fraternal uncles, also assisted in planning the aforementioned rebellion. -

Omni-Joint; Proof of Concept & Comparative Study

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2019 Omni-joint; proof of concept & comparative Study AbdAllah Ezzat AboZaied Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation AboZaied, A. (2019).Omni-joint; proof of concept & comparative Study [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/760 MLA Citation AboZaied, AbdAllah Ezzat. Omni-joint; proof of concept & comparative Study. 2019. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/760 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Sciences and Engineering Omni-Joint: Proof of Concept, & Comparative Study By AbdAllah, Ezzat, AboZaied A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Robotics, Control and Smart Systems (RCSS) Under supervision of: Dr. Mohamed Fawzy Aly Associate Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering February, 2019 i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank; my Parents for supporting my ingenuity, my Wife for standing by my side during hard times, my Daughter for being the joy of my life, my friend Ayman for being there at the beginning working on the Omni-Joint, my closest friend Al-Moatasem for his devotion to help me whenever I need, Dr. Ahmed Hussien (ASU) for his advice that gave me a spark to move to my goal, Dr.