MGNREGA Sameeksha: an Anthology of Research Studies on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(CFT) Risk Management in Emerging Market Banks Good Practice Note

Anti-Money-Laundering (AML) & Countering Financing of Terrorism (CFT) Risk Management in Emerging Market Banks Good Practice Note 1 © International Finance Corporation 2019. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 Internet: www.ifc.org The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The contents of this document are made available solely for general information purposes pertaining to AML/CFT compliance and risk management by emerging markets banks. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. IFC or its affiliates may have an investment in, provide other advice or services to, or otherwise have a financial interest in, certain of the companies and parties that may be named herein. Any reliance you or any other user of this document place on such information is strictly at your own risk. This document may include content provided by third parties, including links and content from third-party websites and publications. IFC is not responsible for the accuracy for the content of any third-party information or any linked content contained in any third-party website. Content contained on such third-party websites or otherwise in such publications is not incorporated by reference into this document. The inclusion of any third-party link or content does not imply any endorsement by IFC nor by any member of the World Bank Group. -

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

Privacy Gaps in India's Digital India Project

Privacy Gaps in India’s Digital India Project AUTHOR Anisha Gupta EDITOR Amber Sinha The Centre for Internet and Society, India Designed by Saumyaa Naidu Shared under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license Introduction Scope The Central and State governments in India have been increasingly taking This paper seeks to assess the privacy protections under fifteen e-governance steps to fulfill the goal of a ‘Digital India’ by undertaking e-governance schemes: Soil Health Card, Crime and Criminal Tracking Network & Systems schemes. Numerous schemes have been introduced to digitize sectors such as (CCTNS), Project Panchdeep, U-Dise, Electronic Health Records, NHRM Smart agriculture, health, insurance, education, banking, police enforcement, Card, MyGov, eDistricts, Mobile Seva, Digi Locker, eSign framework for Aadhaar, etc. With the introduction of the e-Kranti program under the National Passport Seva, PayGov, National Land Records Modernization Programme e-Governance Plan, we have witnessed the introduction of forty four Mission (NLRMP), and Aadhaar. Mode Projects. 1 The digitization process is aimed at reducing the human The project analyses fifteen schemes that have been rolled out by the handling of personal data and enhancing the decision making functions of government, starting from 2010. The egovernment initiatives by the Central the government. These schemes are postulated to make digital infrastructure and State Governments have been steadily increasing over the past five to six available to every citizen, provide on demand governance and services and years and there has been a large emphasis on the development of information digital empowerment. 2 In every scheme, personal information of citizens technology. Various new information technology schemes have been introduced are collected in order to avail their welfare benefits. -

India: Effects of Tariffs and Nontariff Measures on U.S. Agricultural Exports

United States International Trade Commission India: Effects of Tariffs and Nontariff Measures on U.S. Agricultural Exports Investigation No. 332-504 USITC Publication 4107 November 2009 U.S. International Trade Commission COMMISSIONERS Shara L. Aranoff, Chairman Daniel R. Pearson, Vice Chairman Deanna Tanner Okun Charlotte R. Lane Irving A. Williamson Dean A. Pinkert Robert A. Rogowsky Director of Operations Karen Laney-Cummings Director, Office of Industries Address all communications to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 U.S. International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 www.usitc.gov India: Effects of Tariffs and Nontariff Measures on U.S. Agricultural Exports Investigation No. 332-504 Publication 4107 November 2009 This report was prepared principally by the Office of Industries Project Leader George S. Serletis [email protected] Deputy Project Leader Brian Allen [email protected] Laura Bloodgood, Joanna Bonarriva, John Fry, John Giamalva, Katherine Linton, Brendan Lynch, and Marin Weaver Primary Reviewers Alexander Hammer and Deborah McNay Office of Economics Michael Ferrantino, Jesse Mora, Jose Signoret, and Marinos Tsigas Administrative Support Phyllis Boone, Monica Reed, and Wanda Tolson Under the direction of Jonathan R. Coleman, Chief Agriculture and Fisheries Division Abstract This report describes and analyzes policies and other factors that affect U.S. agricultural exports to India. The findings suggest that India’s high agricultural tariffs are a significant impediment to U.S. agricultural exports and that certain Indian nontariff measures (NTMs), including sanitary and phyosanitary measures, substantially limit or effectively prohibit certain U.S. agricultural products. Agriculture is vital to India’s economy, accounting for a substantial share of employment (60 percent) and GDP (17 percent). -

Lessons from Indian Flagship Programmes: the Disconnect for Evaluation Framework 1

Lessons from Indian Flagship Programmes: The Disconnect for Evaluation Framework 1 Abstract This paper critically examines the management information system (MIS) in thirteen Indian flagship programmes that are under operation for quite sometimes now. Yet the MIS for these programmes has not reached maturity and as many as four programmes do not have any MIS. Clearly, there is a disconnect among the information gathering, monitoring and measuring impacts in the development programmes. Key Words: Management information system, Flagship programmes, Log-frame hierarchy, Result-based monitoring and evaluation, Implementation framework Introduction The MIS plays a critical role in the implementation of programme in terms of monitoring periodic progress. A well designed MIS facilitates flow of information among various levels and enables setting up of the necessary feedback mechanism for planning and management of a programme, project or policy. A comprehensive MIS is a necessary condition for taking informed and timely decisions including those related to operational, strategic and tactical ones. A well designed management information system (MIS) must be simple and easy to comprehend by the different stakeholders of the programme at national, sub-national and community levels; and it should provide reliable information. The information should be specific, accurate and verifiable; and facilitate timely management decision in terms of frequency and flow of information (i.e. a two-way feedback system in a decentralized framework), and management of database. Information generated by the system should be easy to access, process and use thereby facilitating wider dissemination and it should be amenable to computer software. However, literature on information system in the national level planning and decision making process is scarce and most of the literature is contextualized to organizations that facilitates managers to take various decisions (Gupta, 1996). -

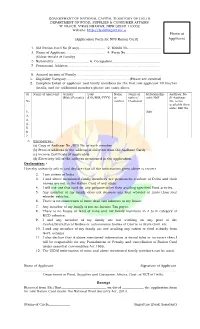

NFS New Ration Card English Form

GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI DEPARTMENT OF FOOD, SUPPLIES & CONSUMER AFFAIRS ‘K’-BLOCK, VIKAS BHAWAN, NEW DELHI-110002 Website: http://fs.delhigovt.nic. in Photo of (Application Form for NFS Ration Card) Applicant 1. Old Ration Card No (If any)......................... 2. Mobile No................................ 3. Name of Applicant...................................... 4. Form No.................................. (Eldest female of Family) 5 Nationality ................................. 6. Occupation.............................................. 7. Permanent Address......................................................................................... ............................................................................................................................. 8. Annual income of Family................................................................................. 1. Eligibility Category............................................................ (Please see overleaf) 2. Complete Detail of applicant and family members (in the first row applicant fill his/her details, and for additional members please use extra sheet. Sr Name of applicant Gender DoB Name Name of Relationship Aadhaar No. (Male/Female) (DD/MM/YYYY) of father/ with HoF (If Aadhaar No mother Husband No. is not . available then enter EID No. 1. Self 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 3. Enclosures:- (a) Copy of Aadhaar No./EID No. of each member (b) Proof of address (if the address is different from the Aadhaar Card) (c) Income Certificate (If applicable) (d) Electricity bill of the address mentioned in the application. Declaration: - I hereby solemnly affirm and declare that all the information given above is correct. 2. I am citizen of India 3. I and above mentioned family members are permanent resident of Delhi and their names are not in the Ration Card of any state. 4. I will not use this card for any purpose other then availing specified Food articles. 5. Any member of my family does not possess any four wheeler or more than four wheeler vehicles. -

TOURISM INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENTS Leveraging Partnerships for Exponential Growth

TOURISM INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENTS Leveraging Partnerships for Exponential Growth THEME PARKS CRUISE INFRASTRUCTURE HEALTHCARE WELLNESS ADVENTURE MICE MEDICAL TITLE Tourism Infrastructure Investments: Leveraging Partnerships for Exponential Growth YEAR July, 2018 AUTHORS STRATEGIC GOVERNMENT ADVISORY (SGA), YES Global Institute, YES BANK No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by photo, photoprint, microfilm or any COPYRIGHT other means without the written permission of YES BANK Ltd. & FICCI. This report is the publication of YES BANK Limited (“YES BANK”) & FICCI and so YES BANK & FICCI have editorial control over the content, including opinions, advice, Statements, services, offers etc. that is represented in this report. However, YES BANK & FICCI will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by the reader’s reliance on information obtained through this report. This report may contain third party contents and third-party resources. YES BANK & FICCI take no responsibility for third party content, advertisements or third party applications that are printed on or through this report, nor does it take any responsibility for the goods or services provided by its advertisers or for any error, omission, deletion, defect, theft or destruction or unauthorized access to, or alteration of, any user communication. Further, YES BANK & FICCI do not assume any responsibility or liability for any loss or damage, including personal injury or death, resulting from use of this report or from any content for communications or materials available on this report. The contents are provided for your reference only. The reader/ buyer understands that except for the information, products and services clearly identified as being supplied by YES BANK & FICCI, it does not operate, control or endorse any information, products, or services appearing in the report in any way. -

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/403 25 November 2020

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/403 25 November 2020 (20-8526) Page: 1/175 Trade Policy Review Body TRADE POLICY REVIEW REPORT BY THE SECRETARIAT INDIA This report, prepared for the seventh Trade Policy Review of India, has been drawn up by the WTO Secretariat on its own responsibility. The Secretariat has, as required by the Agreement establishing the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3 of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization), sought clarification from India on its trade policies and practices. Any technical questions arising from this report may be addressed to Ms Eugenia Lizano (tel.: 022 739 6578), Ms Rohini Acharya (tel.: 022 739 5874), Ms Stéphanie Dorange-Patoret (tel.: 022 739 5497). Document WT/TPR/G/403 contains the policy statement submitted by India. Note: This report is subject to restricted circulation and press embargo until the end of the first session of the meeting of the Trade Policy Review Body on India. This report was drafted in English. WT/TPR/S/403 • India - 2 - CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 8 1 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................ 14 1.1 Main Features of the Economy .................................................................................... 14 1.2 Recent Economic Developments.................................................................................. 14 1.3 Fiscal Policy ............................................................................................................ -

Procedure for Generating Jeevan Pramaan / Digital Life Certificate (Ver1.0)

Procedure for Generating Jeevan Pramaan / Digital Life Certificate (ver1.0) 1. What is Jeevan Pramaan (JP): There are more than one crore pensioners in the country including pensioners from Central Government and Defense personnel. These pensioners get their due pension through Pension Disbursing Authorities (PDAs) such as the banks, the post offices etc. Pensioners are required to furnish a “Life Certificate” to these PDAs in November every year either by presenting themselves personally or by delivering a life certificate in the prescribed format. The requirement to produce this certificate causes huge hardships particularly to the aged and or / infirm pensioners. Launched by Hon. PM Shri. Narendra Modi ji, on 10th Nov 2014, Digital Life Certificate for Pensioners Scheme of the Government of India, known as the Jeevan Pramaan (JP) seeks to address this very problem by digitizing the whole process of securing the life certificate. It enables the pensioner to generate a digital life certificate using a software application and secure Aadhaar based Biometric Authentication System. The Digital Life Certificate (DLC) so generated is stored online & can be accessed by the pensioner & the Pension Disbursing Agency as and when required by them. 2. Components of the J P/ Digital Life Certificate There are three basic components of the Jeevan Pramaan /Digital Life Certificate: A. The Pension Sanctioning Authority (PSAs) It is the authority which approves and sanctions the pension of an individual. The Pension is to be delivered in the Pension Account specified in the Pension Payment Order (PPO). B. The Pension Disbursing Agency (PDAs) The Pension Disbursing Agencies process the DLC of the pensioners. -

Public-Private Partnerships for Health Care in Punjab

- 1 - CASI WORKING PAPER SERIES Number 11-02 09/2011 PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS FOR HEALTH CARE IN PUNJAB NIRVIKAR SINGH Professor of Economics University of California, Santa Cruz CENTER FOR THE ADVANCED STUDY OF INDIA University of Pennsylvania 3600 Market Street, Suite 560 Philadelphia, PA 19104 http://casi.ssc.upenn.edu This project was made possible through the generous support of the Nand & Jeet Khemka Foundation © Copyright 2011 Nirvikar Singh and CASI CENTER FOR THE ADVANCED STUDY OF INDIA © Copyright 2011 Nirvikar Singh and the Center for the Advanced Study of India - 2 - Public-Private Partnerships for Health Care in Punjab NIRVIKAR SINGH CASI Working Paper Series No. 11-02 September 2011 This research was supported by a grant from the Nand and Jeet Khemka Foundation to the Center for Advanced Study of India at the University of Pennsylvania. I am grateful to Devesh Kapur, Nitya Mohan Khemka, Don Mohanlal, Satish Chopra, T. S. Manko, Satinder Singh Sahni and Abhijit Visaria for helpful discussions, comments and guidance. Abhijit Visaria, in particular, played a significant role by doing preliminary and follow-up interviews, some of which I have drawn on in my report, and providing insights and detailed comments on an earlier draft. None of these individuals or organizations is responsible for the opinions expressed here. I am also grateful to numerous individuals throughout India who were extraordinarily generous with their time and insights. I have listed them separately in an Appendix. While I have drawn on these discussions, the views expressed are mine, so I have generally not made individual attributions of statements, and the same disclaimer applies with respect to responsibility for opinions expressed here. -

Guidelines for ASHA and Mahila Arogya Samiti in the Urban Context

Guidelines for ASHA and Mahila Arogya Samiti in the Urban Context NATIONAL URBAN HEALTH MISSION National Urban Health Mission: Guidelines for ASHA and Mahila Arogya Samiti in the Urban Context 1 Keshav Desiraju Hkkjr ljdkj Secretary LokLF;~ ,oa ifjokj't't"!CI5I't dY;k.k foHkkx Tel.:e6~lCr 23061863~ Fax: 23061252 m~ LokLF;~~ qRql'<,oa't't"!CI5I't ifjokjCI5<>'l11 dY;k.k01 flt~ ea=kky; E-mail : [email protected] CI5<>'l1jOj e6~lCr~ ~ m~m~ ~fuekZ.k~qRql'< qRql,<Hkou] CI5<>'l11ubZ fnYyh01 flt~ &.q~ 110011 [email protected] ~Ol ~. Government of India ~ KESHAV DESIRAJU m~ ~ qRql,<o:nf CI5<>'l1jOj~ .q~- 110011 DepartmentGovernment of Healthof India and Family Welfare KESHAVSecretaryDESIRAJU ~Ol ~. o:nf ~ - 110011 DepartmentMinistryof ofHealth Healthand andFamily FamilyWelfare Welfare SecretaryTel. : 23061863 Fax: 23061252 Government of India E-mail: [email protected] Department Ministry ofofNirmanHealthHealth Bhawan,andand FamilyFamily New DelhiWelfareWelfare - 110011 Tel. : 23061863 Fax: 23061252 [email protected] Nirman Shawan, New Delhi- 110011 E-mail: [email protected] Ministry of Health and Family Welfare [email protected] Nirman Shawan, New Delhi- 110011 Message PREFACEMessage Message The launch of the National Urban Health Mission marks an important milestone The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) Strives to Provide Quality Health care to all in the country’s march towards Universal Health Coverage. The underlying principle The citizenslaunch of thethe Nationalcountry Urbanin an equitableHealth Mission manner.marks The an12thimportant five yearmilestone plan has re-affirmed of the NUHM framework is that activities will be designed so that the health needs of in theThecountry'slaunchGovernmentofmarchthe Nationaltowards of India’sUrbanUniversal commitmentHealthHealthMission – “AllCoverage. -

Care of Newborn in the Community and at Home

OPEN Journal of Perinatology (2016) 36, S13–S17 www.nature.com/jp REVIEW Care of newborn in the community and at home SB Neogi1, J Sharma1, M Chauhan1, R Khanna2, M Chokshi1, R Srivastava3, PK Prabhakar3, A Khera3, R Kumar3, S Zodpey1 and VK Paul4 India has contributed immensely toward generating evidence on two key domains of newborn care: Home Based Newborn Care (HBNC) and community mobilization. In a model developed in Gadchiroli (Maharashtra) in the 1990s, a package of Interventions delivered by community health workers during home visits led to a marked decline in neonatal deaths. On the basis of this experience, the national HBNC program centered around Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) was introduced in 2011, and is now the main community- level program in newborn health. Earlier in 2004, the Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illnesses (IMNCI) program was rolled out with inclusion of home visits by Anganwadi Worker as an integral component. IMNCI has been implemented in 505 districts in 27 states and 4 union territories. A mix of Anganwadi Workers, ASHAs, auxiliary nursing midwives (ANMs) was trained. The rapid roll out of IMNCI program resulted in improving quality of newborn care at the ground field. However, since 2012 the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare decided to limit the IMNCI program to ANMs only and leaving the Anganwadi component to the stewardship of the Integrated Child Development Services. ASHAs, the frontline workers for HBNC, receive four rounds of training using two modules. There are a total of over 900 000 ASHAs per link workers in the country, out of which, only 14% have completed the fourth round of training.