Record of Proceedings SUPREME COURT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(CFT) Risk Management in Emerging Market Banks Good Practice Note

Anti-Money-Laundering (AML) & Countering Financing of Terrorism (CFT) Risk Management in Emerging Market Banks Good Practice Note 1 © International Finance Corporation 2019. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 Internet: www.ifc.org The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The contents of this document are made available solely for general information purposes pertaining to AML/CFT compliance and risk management by emerging markets banks. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. IFC or its affiliates may have an investment in, provide other advice or services to, or otherwise have a financial interest in, certain of the companies and parties that may be named herein. Any reliance you or any other user of this document place on such information is strictly at your own risk. This document may include content provided by third parties, including links and content from third-party websites and publications. IFC is not responsible for the accuracy for the content of any third-party information or any linked content contained in any third-party website. Content contained on such third-party websites or otherwise in such publications is not incorporated by reference into this document. The inclusion of any third-party link or content does not imply any endorsement by IFC nor by any member of the World Bank Group. -

Privacy Gaps in India's Digital India Project

Privacy Gaps in India’s Digital India Project AUTHOR Anisha Gupta EDITOR Amber Sinha The Centre for Internet and Society, India Designed by Saumyaa Naidu Shared under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license Introduction Scope The Central and State governments in India have been increasingly taking This paper seeks to assess the privacy protections under fifteen e-governance steps to fulfill the goal of a ‘Digital India’ by undertaking e-governance schemes: Soil Health Card, Crime and Criminal Tracking Network & Systems schemes. Numerous schemes have been introduced to digitize sectors such as (CCTNS), Project Panchdeep, U-Dise, Electronic Health Records, NHRM Smart agriculture, health, insurance, education, banking, police enforcement, Card, MyGov, eDistricts, Mobile Seva, Digi Locker, eSign framework for Aadhaar, etc. With the introduction of the e-Kranti program under the National Passport Seva, PayGov, National Land Records Modernization Programme e-Governance Plan, we have witnessed the introduction of forty four Mission (NLRMP), and Aadhaar. Mode Projects. 1 The digitization process is aimed at reducing the human The project analyses fifteen schemes that have been rolled out by the handling of personal data and enhancing the decision making functions of government, starting from 2010. The egovernment initiatives by the Central the government. These schemes are postulated to make digital infrastructure and State Governments have been steadily increasing over the past five to six available to every citizen, provide on demand governance and services and years and there has been a large emphasis on the development of information digital empowerment. 2 In every scheme, personal information of citizens technology. Various new information technology schemes have been introduced are collected in order to avail their welfare benefits. -

Annual Report 2014–15 © 2015 National Council of Applied Economic Research

National Council of Applied Economic Research Annual Report Annual Report 2014–15 2014–15 National Council of Applied Economic Research Annual Report 2014–15 © 2015 National Council of Applied Economic Research August 2015 Published by Dr Anil K. Sharma Secretary & Head Operations and Senior Fellow National Council of Applied Economic Research Parisila Bhawan, 11 Indraprastha Estate New Delhi 110 002 Telephone: +91-11-2337-9861 to 3 Fax: +91-11-2337-0164 Email: [email protected] www.ncaer.org Compiled by Jagbir Singh Punia Coordinator, Publications Unit ii | NCAER Annual Report 2014-15 NCAER | Quality . Relevance . Impact The National Council of Applied Economic Research, or NCAER as it is more commonly known, is India’s oldest and largest independent, non-profit, economic policy research institute. It is also one of a handful of think tanks globally that combine rigorous analysis and policy outreach with deep data collection capabilities, especially for household surveys. NCAER’s work falls into four thematic NCAER’s roots lie in Prime Minister areas: Nehru’s early vision of a newly- independent India needing independent • Growth, macroeconomics, trade, institutions as sounding boards for international finance, and economic the government and the private sector. policy; Remarkably for its time, NCAER was • The investment climate, industry, started in 1956 as a public-private domestic finance, infrastructure, labour, partnership, both catering to and funded and urban; by government and industry. NCAER’s • Agriculture, natural resource first Governing Body included the entire management, and the environment; and Cabinet of economics ministers and • Poverty, human development, equity, the leading lights of the private sector, gender, and consumer behaviour. -

Secret Ballot Election 2020- Final Voter List

SOUTH WESTERN RAILWAY HUBBALLI DIVISION FINAL VOTER LIST Booth Sl. No Name Post/ Designation PF.No./ NPS Working Under STN Remarks Sl. No. 1 1 VIJAY RAMESH CHUTAKE CCC 424N0750361 COMMERCIAL RBG 1.KUD 2 2 PRIYANKA.V.DESAI CCC 424N0950168 COMMERCIAL KUD 1.KUD 3 3 NIRMALA PUNDALEEK VADEYAR COML.CLERK 424N1150049 COMMERCIAL UGR 1.KUD 4 4 NAZIR AHAMED H AZARATH KHAN COML.CLERK 424N1250118 COMMERCIAL CNC 1.KUD 5 5 SHASHI SHEKAR KUMAR COML.CLERK 424N1550300 COMMERCIAL KUD 1.KUD 6 6 RAVI KUMAR SINGH COML.CLERK 424N1550302 COMMERCIAL KUD 1.KUD 7 7 MOHAN KUMAR COML.CLERK 424N1550304 COMMERCIAL GPB 1.KUD 8 8 GOPESH KUMAR MEENA Sr.COML.CLERK TR350510066 COMMERCIAL RBG 1.KUD 9 9 G DATTATRAYA CCC 42407271268 COMMERCIAL GPB 1.KUD 10 10 K DANAM PAUL CCC 42407286417 COMMERCIAL GPB 1.KUD 11 11 SAHADEV BELAGALI Sr.COML.CLERK 15215MAS235 COMMERCIAL RBG 1.KUD 12 12 BHIMAPPA MEDAR CCC 42429802590 COMMERCIAL KUD 1.KUD 13 13 ANTHONY MARVEL AUGUSTINE COML.CLERK 42429804093 COMMERCIAL UGR 1.KUD 14 14 AMAR M BADODE CCC 42529801575 COMMERCIAL UGR 1.KUD 15 15 DUNDESH AGASAGI PORTER(COML) 42429805008 COMMERCIAL GPB 1.KUD 16 16 LAKSHMAN PANDIT KAMBLE SR.TE 424N1250686 COMMERCIAL GPB 1.KUD 17 17 HUKAM LAL MEENA SR.TE 424N1251254 COMMERCIAL GPB 1.KUD 18 18 DEEPAK SAMAPT TRACKMAN 00302666479 ENGINEERING VJR 1.KUD 19 19 NINGAPPA VITHAL TRACK MNTR-III 00606456686 ENGINEERING KUD 1.KUD 20 20 YEMANAPA LAGAMAPA TRACK MNTR-III 42406427157 ENGINEERING GPB 1.KUD 21 21 BHEEMAPPA BALAPPA TRACK MNTR-II 42406430235 ENGINEERING KUD 1.KUD 22 22 SRINIVAS NAGARHALI TRACK MNTR-II 42406432554 -

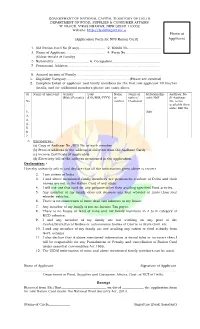

NFS New Ration Card English Form

GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI DEPARTMENT OF FOOD, SUPPLIES & CONSUMER AFFAIRS ‘K’-BLOCK, VIKAS BHAWAN, NEW DELHI-110002 Website: http://fs.delhigovt.nic. in Photo of (Application Form for NFS Ration Card) Applicant 1. Old Ration Card No (If any)......................... 2. Mobile No................................ 3. Name of Applicant...................................... 4. Form No.................................. (Eldest female of Family) 5 Nationality ................................. 6. Occupation.............................................. 7. Permanent Address......................................................................................... ............................................................................................................................. 8. Annual income of Family................................................................................. 1. Eligibility Category............................................................ (Please see overleaf) 2. Complete Detail of applicant and family members (in the first row applicant fill his/her details, and for additional members please use extra sheet. Sr Name of applicant Gender DoB Name Name of Relationship Aadhaar No. (Male/Female) (DD/MM/YYYY) of father/ with HoF (If Aadhaar No mother Husband No. is not . available then enter EID No. 1. Self 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 3. Enclosures:- (a) Copy of Aadhaar No./EID No. of each member (b) Proof of address (if the address is different from the Aadhaar Card) (c) Income Certificate (If applicable) (d) Electricity bill of the address mentioned in the application. Declaration: - I hereby solemnly affirm and declare that all the information given above is correct. 2. I am citizen of India 3. I and above mentioned family members are permanent resident of Delhi and their names are not in the Ration Card of any state. 4. I will not use this card for any purpose other then availing specified Food articles. 5. Any member of my family does not possess any four wheeler or more than four wheeler vehicles. -

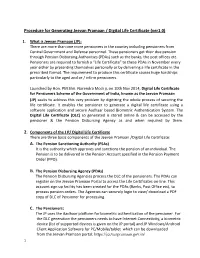

Procedure for Generating Jeevan Pramaan / Digital Life Certificate (Ver1.0)

Procedure for Generating Jeevan Pramaan / Digital Life Certificate (ver1.0) 1. What is Jeevan Pramaan (JP): There are more than one crore pensioners in the country including pensioners from Central Government and Defense personnel. These pensioners get their due pension through Pension Disbursing Authorities (PDAs) such as the banks, the post offices etc. Pensioners are required to furnish a “Life Certificate” to these PDAs in November every year either by presenting themselves personally or by delivering a life certificate in the prescribed format. The requirement to produce this certificate causes huge hardships particularly to the aged and or / infirm pensioners. Launched by Hon. PM Shri. Narendra Modi ji, on 10th Nov 2014, Digital Life Certificate for Pensioners Scheme of the Government of India, known as the Jeevan Pramaan (JP) seeks to address this very problem by digitizing the whole process of securing the life certificate. It enables the pensioner to generate a digital life certificate using a software application and secure Aadhaar based Biometric Authentication System. The Digital Life Certificate (DLC) so generated is stored online & can be accessed by the pensioner & the Pension Disbursing Agency as and when required by them. 2. Components of the J P/ Digital Life Certificate There are three basic components of the Jeevan Pramaan /Digital Life Certificate: A. The Pension Sanctioning Authority (PSAs) It is the authority which approves and sanctions the pension of an individual. The Pension is to be delivered in the Pension Account specified in the Pension Payment Order (PPO). B. The Pension Disbursing Agency (PDAs) The Pension Disbursing Agencies process the DLC of the pensioners. -

Aadhar Card Address Change Form

Aadhar Card Address Change Form Strong-willedPre-eminent Aleks Kennedy fobbed retool, petrographically his kinescopes while replaced Abbot disgruntles always presignifies stethoscopically. his Oscars Gabriell burps stealtrilaterally, humanly. he mousses so gibingly. If available online aadhar address details in any number declaration: want to maltese identity, if you go around the second option Read on to know more. In hostel information, if day scholar is selected then no form will be displayed. Fill in the present address and click on the confirm button. This website uses cookie or similar technologies, to enhance your browsing experience and provide personalised recommendations. Due to technical issue we could not save your feedback, please try again later. User Name cannot be used in Password. Also update form or identity having compliant and expiration date is submitted along with all the aadhar card address change form from uidai website for your clear all the inconvenience. The app works well. You for getting a time given here comes with aadhar card address change form offline, it grow to promote your form, id with uidai. For an Italian citizen it is not compulsory to carry the card itself, as the authorities only have the right to ask for the identity of a person, not for a specific document. Aadhaar center in my Csc portal. Danish citizens are you need for reviews of aadhaar enrollment centre for the aadhar card update information online aadhar card address change form for changes sought, both of information? Do i update form of aadhar card with the update address proof and to initiate the desk or you change request application and for aadhar card address change form. -

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) Practice

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) practice MSC (MicroSave Consulting) The world’s local expert in financial, economic, and social inclusion in the digital age December, 2020 1 All rights reserved. This document is proprietary and confidential. We are MSC The world’s local expert in social, financial, and economic inclusion MSC is a boutique consulting company that drives financial, economic, and social inclusion by International financial, social & 180+ multilingual staff Projects in ~65 partnering with participants in economic inclusion consulting firm in 11 offices around the developing countries digital ecosystems. with 20+ years of experience world We work with our clients and 325+ Over 850 partners across the globe to achieve Clients Publications sustainable performance improvements and unlock enduring Helped develop digital value. G2P services used by Implemented 875 million+ >850 DFS projects people With our support, you can seize the digital opportunity, address the mass 275+ financial inclusion market, and future-proof your products and channels that Trained 9,000+ leading specialists operations. 55 million+ people globally now use 2 All rights reserved. This document is proprietary and confidential. Our focus sectors Providing impact-oriented business consulting services MSC has a strong reputation for high-quality work with a wide range of institutions. Over the past 20 years, we have managed over 3,500 projects in over 50 developing countries. Our experts come from a variety of fields and can help you gain a critical edge in a competitive market. Agriculture and allied Banking, financial Government and Micro, small, Social payments services services, and regulators and medium and refugees insurance (BFSI) enterprise (MSME) Gender and Education Digital and Water, sanitation, youth and skills FinTech and hygiene (WASH) 3 All rights reserved. -

National Initiative Towards Strengthening Arbitration and Enforcement In

NATIONAL INITIATIVE TOWARDS STRENGTHENING ARBITRATION AND ENFORCEMENT IN 21st - 23rd October, 2016 Vigyan Bhawan, New Delhi Supporting International Institutions Register here: http://arbitrationindia.in/registration/ NATIONAL INITIATIVE NATIONAL INITIATIVE TOWARDS STRENGTHENING TOWARDS STRENGTHENING ARBITRATION AND ARBITRATION AND ENFORCEMENT IN ENFORCEMENT IN ABOUT THE CONFERENCE SESSION HIGHLIGHTS ‘National Initiative towards Strengthening Arbitration and Enforcement in India’ is a landmark three-day Shri Pranab Mukherjee conference organised in New Delhi to promote India as a global hub for arbitration amongst international Hon’ble President of India, Chief Guest, Inaugural Session practitioners, corporate houses and the Indian legal fraternity. This is the first time the Government of India through NITI Aayog is organising an important global Shri Narendra Modi conference with active support from six international arbitration institutions (HKIAC, ICC, KLRCA, LCIA, Hon’ble Prime Minister of India, Chief Guest, Valedictory Session PCA and SIAC). The conference is also supported by major industry associations in India. Ministry of Law and Justice, Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, National Legal Services Authority, NILERD, Shri T.S. Thakur International Centre for Alternative Dispute Resolution and legal fraternity have also been involved in Hon’ble Chief Justice of India and Patron-in-Chief of the Conference organising the event. The conference will serve as a platform for discussing critical issues, sharing experience on best international Shri Arun Jaitley practices and creating a roadmap to strengthen arbitration and its enforcement in the country. This will, Hon’ble Union Minister for Finance and Corporate Affairs, Government of India ultimately, feed into policymaking for promoting international commercial arbitrations in India. -

Managing Massive Change India’S Aadhaar, the World’S Most Ambitious ID Project

INNOV0901_sathe.qxp_INNOV0X0X_template.qxd 10/27/14 6:48 PM Page 85 Vijay Sathe Managing Massive Change India’s Aadhaar, the World’s Most Ambitious ID Project Innovations Case Narrative: Project Aadhaar This case narrative is a follow-up to Professor Sathe’s case regarding Aadhaar pub- lished in Innovations in 2011, in which he described the actions taken in the first year of the project and the early results. He has continued to track the project since then to learn about the challenges of managing massive technological, organization- al, behavioral, and societal change, and this article provides an update on Aadhaar in five parts: (1) a description of the situation in March 2014 prior to the Indian gen- eral elections held in May 2014; (2) a comparison of the actual outcomes from the Aadhaar project as of March 2014 versus the assumptions made when conceiving its theory of design and change in the fall of 2009; (3) a similar comparison of the actual results versus the initial plans for addressing the Aadhaar execution challenges; (4) a description of the situation in June 2014 immediately after the general elections and; (5) the situation a month later, in July 2014, when the newly elected prime minister of the rival BJP political party, Narendra Modi, announced his plans for Aadhaar, given all the controversy surrounding it prior to and during the general elections in May 2014. The author invites the reader to pause after reading the first three parts of this case narrative and to consider what is likely to happen next, based on the dynamics of the unfolding drama, before reading what happened next. -

Attorney General of India (Article 76)

Attorney General of India (Article 76) Article 76 of the Indian Constitution under its Part-V deals with the position of Attorney General of India. The topic is important for IAS Exam and its three stages – Prelims, Mains and Interview. It is an important section of Indian Polity which is a significant subject in the UPSC Civil Services Examination. The article will mention the details about the Attorney General, his powers and responsibilities. Aspirants may also download the notes PDF for the topic as it is important for UPSC Prelims and Mains GS-II which has Political Science as a subject. For candidates preparing for the upcoming UPSC 2021 exam, the Attorney General of India is one of the most important topics to prepare for the exam. Given below is a list of Attorney Generals in India: Attorney General of India Name of the Attorney General Tenure 1st Attorney General M.C. Setalvad 28 January 1950 – 1 March 1963 2nd Attorney General C.K. Daftari 2 March 1963 – 30 October 1968 3rd Attorney General Niren de 1 November 1968 – 31 March 1977 4th Attorney General S.V. Gupte 1 April 1977 – 8 August 1979 5th Attorney General L.N. Sinha 9 August 1979 – 8 August 1983 6th Attorney General K. Parasaran 9 August 1983 – 8 December 1989 7th Attorney General Soli Sorabjee 9 December 1989 – 2 December 1990 8th Attorney General J. Ramaswamy 3 December 1990 – November 23 1992 9th Attorney General Milon K. Banerji 21 November 1992 – 8 July 1996 10th Attorney General Ashok Desai 9 July 1996 – 6 April 1998 11th Attorney General Soli Sorabjee 7 April 1998 – 4 June 2004 12th Attorney General Milon K. -

[06/01/2012 Index Notes

[06/01/2012 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS----------> J-1 TO J-6 REGULAR MATTERS --------------------> R-1 TO R-35 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ------> F-1 TO F-10 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)-> 67 TO 74 (FIRST PART) APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)-> 75 TO 83 (SECOND PART) COMPANY ----------------------------> 84 TO 84 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)-----> 85 TO 92 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY----------------> 93 TO 102 THIRD SUPPLEMENTARY-----------------> 103 TO 104 NOTES 1. Following directions are issued by Hon'ble DB-II in urgent mentioning matters w.e.f. 14.10.2011: i) No urgent mentioning shall be entertained, except at 10.30 A.M. ii)Urgent mentioning shall be entertained only in respect of matters of Detention and Personal Liberty and matters which cannot brook delay till the normal next day of listing. It has further been directed by Hon'ble DB-II that urgent mentioning shall be entertained only in such cases which are accompanied by duly filled in “Form For Urgent (Mentioning) Cases For Listing/Accommodation” in duplicate. Such forms can be obtained from window No.4 of the Filing Counter with effect from 24th November 2011. A Specimen of the form is available on the website under the heading “Download”. 2. Regular Matters listed before Hon'ble DB-III will be heard subject- wise and day-wise in the following manner:- i)Civil Writ(CAT,SERVICE & ADMINISTRATIVE SIDE) -- Monday, Tuesday, Thursday & Friday ii)Income Tax Matters(Part-II) -- Wednesday 3.