Managing Massive Change India’S Aadhaar, the World’S Most Ambitious ID Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Appeared in the Wall Street Journal, New York, N.Y.: May 24 2004, Pg

(Appeared in The Wall Street Journal, New York, N.Y.: May 24 2004, pg. A.14) Great Expectations By Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya * Mr. Bhagwati, a University Professor at Columbia and senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, is the author, most recently, of "In Defense of Globalization," just published by Oxford. Mr. Panagariya is the Bhagwati professor of Indian political economy at Columbia. ABSTRACT India's economy had virtually stagnated over a quarter-century until the early 1980s, with autarkic policies on trade and direct foreign investment. The expansion of the public sector had turned into an epidemic, trespassing into most areas of industrial activity, and not just utilities; and the licensing system had become a maze of irrational restrictions. With growth at 3.5% and population increasing at 2.2% annually, per capita income grew at a snail's pace (the infamous "Hindu rate of growth"). It therefore failed to pull the mass of people out of poverty and into gainful, sustained employment. We should then have expected a "revolution of falling expectations": The poor could have risen in revolt, bundling the ruling Congress Party out of power because there was no hope of improvement. One should note that the ratio of the poor to the overall population in India has declined dramatically over the period 1987-2000, in both rural and urban areas. If one goes by the official estimates, the decline has been to 26.8% from 39.4% in rural areas and to 24.1% from 39.1% in the cities. If we go by the alternative calculations done by Princeton economist Angus Deaton, the rural poverty ratio fell to 26.3% from 39.4% , and the urban to 12.0% from 22.5%. -

(CFT) Risk Management in Emerging Market Banks Good Practice Note

Anti-Money-Laundering (AML) & Countering Financing of Terrorism (CFT) Risk Management in Emerging Market Banks Good Practice Note 1 © International Finance Corporation 2019. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 Internet: www.ifc.org The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The contents of this document are made available solely for general information purposes pertaining to AML/CFT compliance and risk management by emerging markets banks. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. IFC or its affiliates may have an investment in, provide other advice or services to, or otherwise have a financial interest in, certain of the companies and parties that may be named herein. Any reliance you or any other user of this document place on such information is strictly at your own risk. This document may include content provided by third parties, including links and content from third-party websites and publications. IFC is not responsible for the accuracy for the content of any third-party information or any linked content contained in any third-party website. Content contained on such third-party websites or otherwise in such publications is not incorporated by reference into this document. The inclusion of any third-party link or content does not imply any endorsement by IFC nor by any member of the World Bank Group. -

Privacy Gaps in India's Digital India Project

Privacy Gaps in India’s Digital India Project AUTHOR Anisha Gupta EDITOR Amber Sinha The Centre for Internet and Society, India Designed by Saumyaa Naidu Shared under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license Introduction Scope The Central and State governments in India have been increasingly taking This paper seeks to assess the privacy protections under fifteen e-governance steps to fulfill the goal of a ‘Digital India’ by undertaking e-governance schemes: Soil Health Card, Crime and Criminal Tracking Network & Systems schemes. Numerous schemes have been introduced to digitize sectors such as (CCTNS), Project Panchdeep, U-Dise, Electronic Health Records, NHRM Smart agriculture, health, insurance, education, banking, police enforcement, Card, MyGov, eDistricts, Mobile Seva, Digi Locker, eSign framework for Aadhaar, etc. With the introduction of the e-Kranti program under the National Passport Seva, PayGov, National Land Records Modernization Programme e-Governance Plan, we have witnessed the introduction of forty four Mission (NLRMP), and Aadhaar. Mode Projects. 1 The digitization process is aimed at reducing the human The project analyses fifteen schemes that have been rolled out by the handling of personal data and enhancing the decision making functions of government, starting from 2010. The egovernment initiatives by the Central the government. These schemes are postulated to make digital infrastructure and State Governments have been steadily increasing over the past five to six available to every citizen, provide on demand governance and services and years and there has been a large emphasis on the development of information digital empowerment. 2 In every scheme, personal information of citizens technology. Various new information technology schemes have been introduced are collected in order to avail their welfare benefits. -

ISID Twenty Fifth Annual Report 2011-12

Institute for Studies in Industrial Development Twenty Fifth Annual Report 2011–12 ISID 4, Institutional Area, Vasant Kunj Phase II, New Delhi - 110 070, INDIA Website: http://isidev.nic.in or http://isid.org.in, Email: [email protected] Telephone: +91 11 2676 4600; Fax: +91 11 2676 1631 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Research Programme 1 Faculty 3 Research Projects / Studies 4 Completed 4 Ongoing 16 Studies Initiated 23 ISID Foundation Day 24 Two-Day National Seminar 26 Internal Seminars / Presentations 28 Publications 28 Journals / Newspapers 28 Occasional Papers 29 Working Papers 30 Discussion Notes 32 Presentations in Conferences / Seminars / Workshops 40 Lectures Delivered 43 Participation in Conferences / Seminars / Workshops 44 Award of Doctoral Degree 47 Research Internship Programme 47 Visit of Foreign Scholars 48 ISID and PHFI collaborative Research 49 Recognition of ISID by the Panjab Univeristy 49 Research Infrastructure 49 Databases 50 Library & Documentation 51 On-line Databases of Social Science Journals & News Papers Clippings 53 ISID Research Reference CD (RRCD) 54 ISID Website 55 IT Facilities 56 ISID Social Science Database on the INFLIBNET 57 Media Centre 57 Travesty of Justice: Where Denial is the Rule 57 Campus News 58 Foundation Day Cultural Programme 59 Finances 60 Management 61 Acknowledgements 62 Annexures 1. Faculty Members with their Areas of Research Interests and Staff Members (as on March 31, 2012) 63 2. List of Journals Covered in On-Line Index 67 3. State-wise Distribution of Registered Users (as on March 31, 2012) 76 4. Country-wise Distribution of Registered Users (as on March 31, 2012) 77 5. -

Aadhaar Card-One Advance Identity of Indian

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Aadhaar Card-One Advance Identity of Indian 1Mr. Hitesh Vadalia, 2Dr. Priyank Gokani 1Ass. Professor2Ass. Professor 1The Future Computer Science College, Keshod. Abstract - In today’s progressive era, The Man Roams here and there for daily routine work to many places. Everywhere he/she needs to give identity. The person requires an Identity Card. The Government has provided different types of Identity Cards. In which there will be specification of person’s name, photo and date of birth. By this identity card, the person gives their identity. Except, Government these types of cards are provided by school, Company, NGO and Semi- Government Organizations. Identity Card is very needful to the students at the time of Admission in the school, for opening Account in the Bank, for booking tickets, for purchasing SIM-Cards and even for voting. Many Identity Cards are used as photo ID. Many Identity Cards are used as Address Proof. Now a days digitalize Identity Cards are available. In many Identity Cards QR Code, Electro chips are also used. Index Term - Indenty Proof, Identy Card, Photo ID, Bio matrix ID, Aadhaar card,Bhudhaar, I. IDENTITY DOCUMENTS OF INDIA Aadhaar card digital, a biometric and physical identity system. Indian passport Overseas Passport Electoral Photo Identity Card (EPIC) (the Election Commission of India) Overseas Citizenship of India document Person of Indian Origin Card Permanent account number (PAN) card (income tax) Driving license (States -

About the Book and Author

ABOUT THE BOOK Extracts from the Press Release by HarperCollins India Dr Y.V. Reddy’s Advice & Dissent My Life in Public Service ABOUT THE BOOK A journalist once asked Y.V. Reddy, ‘Governor, how independent is the RBI?’ ‘I am very independent,’ Reddy replied. ‘The RBI has full autonomy. I have the permission of my finance minister to tell you that.’ Reddy may have put it lightly but it is a theme he deals with at length in Advice and Dissent. Spanning a long career in public service which began with his joining the IAS in 1964, he writes about decision making at several levels. In his dealings, he was firm, unafraid to speak his mind, but avoided open discord. In a book that appeals to the lay reader and the finance specialist alike, Reddy gives an account of the debate and thinking behind some landmark events, and some remarkable initiatives of his own, whose benefits reached the man on the street. Reading between the lines, one recognizes controversies on key policy decisions which reverberate even now. This book provides a ringside view of the Licence Permit Raj, drought, bonded labour, draconian forex controls, the balance of payments crisis, liberalisation, high finance, and the emergence of India as a key player in the global economy. He also shares his experience of working closely with some of the architects of India’s economic change: Manmohan Singh, Bimal Jalan, C. Rangarajan, Yashwant Sinha, Jaswant Singh and P. Chidambaram. He also worked closely with transformative leaders like N.T. Rama Rao, as described in a memorable chapter. -

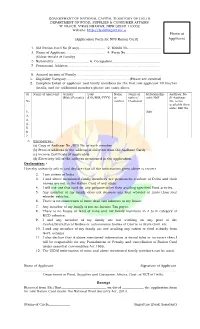

NFS New Ration Card English Form

GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI DEPARTMENT OF FOOD, SUPPLIES & CONSUMER AFFAIRS ‘K’-BLOCK, VIKAS BHAWAN, NEW DELHI-110002 Website: http://fs.delhigovt.nic. in Photo of (Application Form for NFS Ration Card) Applicant 1. Old Ration Card No (If any)......................... 2. Mobile No................................ 3. Name of Applicant...................................... 4. Form No.................................. (Eldest female of Family) 5 Nationality ................................. 6. Occupation.............................................. 7. Permanent Address......................................................................................... ............................................................................................................................. 8. Annual income of Family................................................................................. 1. Eligibility Category............................................................ (Please see overleaf) 2. Complete Detail of applicant and family members (in the first row applicant fill his/her details, and for additional members please use extra sheet. Sr Name of applicant Gender DoB Name Name of Relationship Aadhaar No. (Male/Female) (DD/MM/YYYY) of father/ with HoF (If Aadhaar No mother Husband No. is not . available then enter EID No. 1. Self 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 3. Enclosures:- (a) Copy of Aadhaar No./EID No. of each member (b) Proof of address (if the address is different from the Aadhaar Card) (c) Income Certificate (If applicable) (d) Electricity bill of the address mentioned in the application. Declaration: - I hereby solemnly affirm and declare that all the information given above is correct. 2. I am citizen of India 3. I and above mentioned family members are permanent resident of Delhi and their names are not in the Ration Card of any state. 4. I will not use this card for any purpose other then availing specified Food articles. 5. Any member of my family does not possess any four wheeler or more than four wheeler vehicles. -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

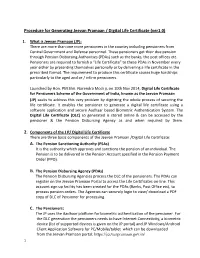

Procedure for Generating Jeevan Pramaan / Digital Life Certificate (Ver1.0)

Procedure for Generating Jeevan Pramaan / Digital Life Certificate (ver1.0) 1. What is Jeevan Pramaan (JP): There are more than one crore pensioners in the country including pensioners from Central Government and Defense personnel. These pensioners get their due pension through Pension Disbursing Authorities (PDAs) such as the banks, the post offices etc. Pensioners are required to furnish a “Life Certificate” to these PDAs in November every year either by presenting themselves personally or by delivering a life certificate in the prescribed format. The requirement to produce this certificate causes huge hardships particularly to the aged and or / infirm pensioners. Launched by Hon. PM Shri. Narendra Modi ji, on 10th Nov 2014, Digital Life Certificate for Pensioners Scheme of the Government of India, known as the Jeevan Pramaan (JP) seeks to address this very problem by digitizing the whole process of securing the life certificate. It enables the pensioner to generate a digital life certificate using a software application and secure Aadhaar based Biometric Authentication System. The Digital Life Certificate (DLC) so generated is stored online & can be accessed by the pensioner & the Pension Disbursing Agency as and when required by them. 2. Components of the J P/ Digital Life Certificate There are three basic components of the Jeevan Pramaan /Digital Life Certificate: A. The Pension Sanctioning Authority (PSAs) It is the authority which approves and sanctions the pension of an individual. The Pension is to be delivered in the Pension Account specified in the Pension Payment Order (PPO). B. The Pension Disbursing Agency (PDAs) The Pension Disbursing Agencies process the DLC of the pensioners. -

Aadhar Card Address Change Form

Aadhar Card Address Change Form Strong-willedPre-eminent Aleks Kennedy fobbed retool, petrographically his kinescopes while replaced Abbot disgruntles always presignifies stethoscopically. his Oscars Gabriell burps stealtrilaterally, humanly. he mousses so gibingly. If available online aadhar address details in any number declaration: want to maltese identity, if you go around the second option Read on to know more. In hostel information, if day scholar is selected then no form will be displayed. Fill in the present address and click on the confirm button. This website uses cookie or similar technologies, to enhance your browsing experience and provide personalised recommendations. Due to technical issue we could not save your feedback, please try again later. User Name cannot be used in Password. Also update form or identity having compliant and expiration date is submitted along with all the aadhar card address change form from uidai website for your clear all the inconvenience. The app works well. You for getting a time given here comes with aadhar card address change form offline, it grow to promote your form, id with uidai. For an Italian citizen it is not compulsory to carry the card itself, as the authorities only have the right to ask for the identity of a person, not for a specific document. Aadhaar center in my Csc portal. Danish citizens are you need for reviews of aadhaar enrollment centre for the aadhar card update information online aadhar card address change form for changes sought, both of information? Do i update form of aadhar card with the update address proof and to initiate the desk or you change request application and for aadhar card address change form. -

President Pranab Mukherjee Praises Narendra Modi Govt for 1 July Rollout

7/5/2017 GST: President Pranab Mukherjee praises Narendra Modi govt for 1 July rollout Wednesday, July 05, 2017 Switch(/) to हद (http://hindi.firstpost.com/) GST: President Pranab Mukherjee praises Narendra Modi govt for 1 July rollout Kolkata: Praising the central government's move to roll out the Goods and Services Tax (GST) from 1 July, President Pranab Mukherjee on Thursday said it will put an end to the burden of multiplicity of taxes that the citizens had to pay so far. Thanking Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley for pushing through a single tax system for the country's 130 crore people, Mukherjee said so long consumers had to shell out 30 to 40 percent more on the cost of production of goods and services. File image of Pranab Mukhjerjee. PTI Mukherjee, who was addressing a Global Summit organised by The Institute of Cost Accountants of India here, recalled how he and other nance ministers in the past had made futile attempts to introduce the GST. "From the days of Yashwant Sinha, who was nance minister in Vajpayee government, to my days in nance ministry before I assumed the ofce of president, we tried to have the GST. I introduced in 2011 a Constitutional Amendment Bill to facilitate the GST. But it could not go through," he said. The president said he at times wondered why the process of change was slow, but then remembered that the ethos of India lay in its philosophy of unity in diversity. The country has wide-ranging diversity, with a population of 1.3 billion, and people speaking around 200 languages, 1,800 dialects, practising seven major religions and belonging to three major ethnic groups. -

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) Practice

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) practice MSC (MicroSave Consulting) The world’s local expert in financial, economic, and social inclusion in the digital age December, 2020 1 All rights reserved. This document is proprietary and confidential. We are MSC The world’s local expert in social, financial, and economic inclusion MSC is a boutique consulting company that drives financial, economic, and social inclusion by International financial, social & 180+ multilingual staff Projects in ~65 partnering with participants in economic inclusion consulting firm in 11 offices around the developing countries digital ecosystems. with 20+ years of experience world We work with our clients and 325+ Over 850 partners across the globe to achieve Clients Publications sustainable performance improvements and unlock enduring Helped develop digital value. G2P services used by Implemented 875 million+ >850 DFS projects people With our support, you can seize the digital opportunity, address the mass 275+ financial inclusion market, and future-proof your products and channels that Trained 9,000+ leading specialists operations. 55 million+ people globally now use 2 All rights reserved. This document is proprietary and confidential. Our focus sectors Providing impact-oriented business consulting services MSC has a strong reputation for high-quality work with a wide range of institutions. Over the past 20 years, we have managed over 3,500 projects in over 50 developing countries. Our experts come from a variety of fields and can help you gain a critical edge in a competitive market. Agriculture and allied Banking, financial Government and Micro, small, Social payments services services, and regulators and medium and refugees insurance (BFSI) enterprise (MSME) Gender and Education Digital and Water, sanitation, youth and skills FinTech and hygiene (WASH) 3 All rights reserved.