Helianthemum Apenninum (L.) Mill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ectomycorrhizal Fungal Communities at Forest Edges 93, 244–255 IAN A

Journal of Blackwell Publishing, Ltd. Ecology 2005 Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities at forest edges 93, 244–255 IAN A. DICKIE and PETER B. REICH Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota, St Paul, MN, USA Summary 1 Ectomycorrhizal fungi are spatially associated with established ectomycorrhizal vegetation, but the influence of distance from established vegetation on the presence, abundance, diversity and community composition of fungi is not well understood. 2 We examined mycorrhizal communities in two abandoned agricultural fields in Minnesota, USA, using Quercus macrocarpa seedlings as an in situ bioassay for ecto- mycorrhizal fungi from 0 to 20 m distance from the forest edge. 3 There were marked effects of distance on all aspects of fungal communities. The abundance of mycorrhiza was uniformly high near trees, declined rapidly around 15 m from the base of trees and was uniformly low at 20 m. All seedlings between 0 and 8 m distance from forest edges were ectomycorrhizal, but many seedlings at 16–20 m were uninfected in one of the two years of the study. Species richness of fungi also declined with distance from trees. 4 Different species of fungi were found at different distances from the edge. ‘Rare’ species (found only once or twice) dominated the community at 0 m, Russula spp. were dominants from 4 to 12 m, and Astraeus sp. and a Pezizalean fungus were abundant at 12 m to 20 m. Cenococcum geophilum, the most dominant species found, was abundant both near trees and distant from trees, with lowest relative abundance at intermediate distances. 5 Our data suggest that seedlings germinating at some distance from established ecto- mycorrhizal vegetation (15.5 m in the present study) have low levels of infection, at least in the first year of growth. -

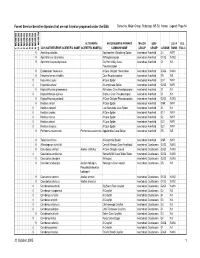

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR -

Molecular Systematics, Character Evolution, and Pollen Morphology of Cistus and Halimium (Cistaceae)

Molecular systematics, character evolution, and pollen morphology of Cistus and Halimium (Cistaceae) Laure Civeyrel • Julie Leclercq • Jean-Pierre Demoly • Yannick Agnan • Nicolas Que`bre • Ce´line Pe´lissier • Thierry Otto Abstract Pollen analysis and parsimony-based phyloge- pollen. Two Halimium clades were characterized by yellow netic analyses of the genera Cistus and Halimium, two flowers, and the other by white flowers. Mediterranean shrubs typical of Mediterranean vegetation, were undertaken, on the basis of cpDNA sequence data Keywords TrnL-F ÁTrnS-G ÁPollen ÁExine ÁCistaceae Á from the trnL-trnF, and trnS-trnG regions, to evaluate Cistus ÁHalimium limits between the genera. Neither of the two genera examined formed a monophyletic group. Several mono- phyletic clades were recognized for the ingroup. (1) The Introduction ‘‘white and whitish pink Cistus’’, where most of the Cistus sections were present, with very diverse pollen ornamen- Specialists on the Cistaceae usually acknowledge eight tations ranging from striato-reticulate to largely reticulate, genera for this family (Arrington and Kubitzki 2003; sometimes with supratectal elements; (2) The ‘‘purple pink Dansereau 1939; Guzma´n and Vargas 2009; Janchen Cistus’’ clade grouping all the species with purple pink 1925): Cistus, Crocanthemum, Fumana, Halimium, flowers belonging to the Macrostylia and Cistus sections, Helianthemum, Hudsonia, Lechea and Tuberaria (Xolantha). with rugulate or microreticulate pollen. Within this clade, Two of these, Lechea and Hudsonia, occur in North the pink-flowered endemic Canarian species formed a America, and Crocanthemum is present in both North monophyletic group, but with weak support. (3) Three America and South America. The other genera are found in Halimium clades were recovered, each with 100% boot- the northern part of the Old World. -

Germination and in Vitro Multiplication of Helianthemum Kahiricum, a Threatened Plant in Tunisia Arid Areas

Vol. 14(12), pp. 1009-1014, 25 March, 2015 DOI: 10.5897/AJB2014.13709 Article Number: 2B3138551682 ISSN 1684-5315 African Journal of Biotechnology Copyright © 2015 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB Full Length Research Paper Germination and in vitro multiplication of Helianthemum kahiricum, a threatened plant in Tunisia arid areas HAMZA Amina* and NEFFATI Mohamed Range Ecology Laboratory, Arid Lands Institute of Médenine, 4119 Médenine, Tunisia. Received 9 February, 2014; Accepted 9 February, 2015 Seeds of Helianthemum kahiricum have an excellent germination rate extending to about 90% within short time not more than four days after scarification (mechanical treatment) and a good protocol of disinfection. A high frequency of sprouting and shoot differentiation was observed in the primary cultures of nodal explants of H. kahiricum on Murashige and Skoog medium (MS) free growth regulators or with less concentration of kinetin (0.5 mg L-1 or 1.0 mg L-1 kin). In vitro proliferated shoot were multiplied rapidly by culture of shoot tips on MS with kinetin (0.5 mg L-1) which produced the greatest multiple shoot formation. The kinetin had a positive effect on the multiplication and growth, but a concentration that exceeded 2.0 mg.L-1 decreased the growth. A high frequency of rooting with development of healthy roots was observed from shoots cultured on MS/8 medium hormone-free. Key words: Helianthemum kahiricum, in vitro germination, multiplication, axillary buds. INTRODUCTION Helianthemum kahiricum (called R'guiga or Chaal in arranged in 5-l2-flowered and 1-sided inflorescence. -

Research on Spontaneous and Subspontaneous Flora of Botanical Garden "Vasile Fati" Jibou

Volume 19(2), 176- 189, 2015 JOURNAL of Horticulture, Forestry and Biotechnology www.journal-hfb.usab-tm.ro Research on spontaneous and subspontaneous flora of Botanical Garden "Vasile Fati" Jibou Szatmari P-M*.1,, Căprar M. 1 1) Biological Research Center, Botanical Garden “Vasile Fati” Jibou, Wesselényi Miklós Street, No. 16, 455200 Jibou, Romania; *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract The research presented in this paper had the purpose of Key words inventory and knowledge of spontaneous and subspontaneous plant species of Botanical Garden "Vasile Fati" Jibou, Salaj, Romania. Following systematic Jibou Botanical Garden, investigations undertaken in the botanical garden a large number of spontaneous flora, spontaneous taxons were found from the Romanian flora (650 species of adventive and vascular plants and 20 species of moss). Also were inventoried 38 species of subspontaneous plants, adventive plants, permanently established in Romania and 176 vascular plant floristic analysis, Romania species that have migrated from culture and multiply by themselves throughout the garden. In the garden greenhouses were found 183 subspontaneous species and weeds, both from the Romanian flora as well as tropical plants introduced by accident. Thus the total number of wild species rises to 1055, a large number compared to the occupied area. Some rare spontaneous plants and endemic to the Romanian flora (Galium abaujense, Cephalaria radiata, Crocus banaticus) were found. Cultivated species that once migrated from culture, accommodated to environmental conditions and conquered new territories; standing out is the Cyrtomium falcatum fern, once escaped from the greenhouses it continues to develop on their outer walls. Jibou Botanical Garden is the second largest exotic species can adapt and breed further without any botanical garden in Romania, after "Anastasie Fătu" care [11]. -

On the Identity of Helianthemum Mathezii and H. Pomeridianum (Cistaceae)

Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid 74 (2): e060 http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/ajbm.2472 ISSN: 0211-1322 [email protected], http://rjb.revistas.csic.es/index.php/rjb Copyright: © 2017 CSIC. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial (by-nc) Spain 3.0 License. On the identity of Helianthemum mathezii and H. pomeridianum (Cistaceae) Abelardo Aparicio 1,* & Rafael G. Albaladejo 2 1,2 Dept. of Plant Biology and Ecology, Universidad de Sevilla, Spain * Corresponding author: [email protected], http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7122-4421 2 [email protected], http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2101-5204 Abstract. The original description of Helianthemum mathezii regarded Resumen. En la descripción original de Helianthemum mathezii se the species to be a therophyte. However, the detailed observation of the considera esta especie como un terofito. Sin embargo, la observación holotype of H. mathezii, as well as newly collected specimens from the minuciosa de su holotipo, así como de otros especímenes recientemente type locality, does not support its condition of annual plant. Further study recolectados en la misma localidad del tipo, sugiere que no se trata has led to the conclusion that all these plants can readily be identified as de una planta anual. Concluimos que estas plantas pueden ser bien H. pomeridianum; the descriptions of H. mathezii and H. pomeridianum identificadas como H. pomeridianum; las descripciones de H. mathezii y H. pomeridianum son similares excepto en lo referido a su hábito, la are equivalent except for the habit, being the former annual and the primera supuestamente es una planta anual y la segunda sufruticosa. -

LIFE and Endangered Plants: Conserving Europe's Threatened Flora

L I F E I I I LIFE and endangered plants Conserving Europe’s threatened flora colours C/M/Y/K 32/49/79/21 European Commission Environment Directorate-General LIFE (“The Financial Instrument for the Environment”) is a programme launched by the European Commission and coordinated by the Environment Directorate-General (LIFE Unit - E.4). The contents of the publication “LIFE and endangered plants: Conserving Europe’s threatened flora” do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the institutions of the European Union. Authors: João Pedro Silva (Technical expert), Justin Toland, Wendy Jones, Jon Eldridge, Edward Thorpe, Maylis Campbell, Eamon O’Hara (Astrale GEIE-AEIDL, Communications Team Coordinator). Managing Editor: Philip Owen, European Commission, Environment DG, LIFE Unit – BU-9, 02/1, 200 rue de la Loi, B-1049 Brussels. LIFE Focus series coordination: Simon Goss (LIFE Communications Coordinator), Evelyne Jussiant (DG Environment Communications Coordinator). The following people also worked on this issue: Piotr Grzesikowski, Juan Pérez Lorenzo, Frank Vassen, Karin Zaunberger, Aixa Sopeña, Georgia Valaoras, Lubos Halada, Mikko Tira, Michele Lischi, Chloé Weeger, Katerina Raftopoulou. Production: Monique Braem. Graphic design: Daniel Renders, Anita Cortés (Astrale GEIE-AEIDL). Acknowledgements: Thanks to all LIFE project beneficiaries who contributed comments, photos and other useful material for this report. Photos: Unless otherwise specified; photos are from the respective projects. This issue of LIFE Focus is published in English with a print-run of 5,000 copies and is also available online. Attention version papier ajouter Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. New freephone number: 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 Additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. -

Butterflies of the Italian Dolomites

Butterflies of the Italian Dolomites Naturetrek Tour Report 8 -15 July 2012 Mountain Clouded Yellow Meadow at Gardeccia 2012 Naturetrek Group at Val Venegia Titania’s Fritillary Report and images compiled by Alan Miller Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Butterflies of the Italian Dolomites Tour Leader: Alan Miller Participants: Judy Copeland Margaret Gorely Wendy Simons Day 1 Sunday 8th July Venice Airport to Tamion via the Agordo Gorge Weather: Fine, sunny and hot with a little high cloud over the mountains. 32 degrees at Venice Airport, 28 degrees at Tamion Alan was in Venice having just said goodbye to another Dolomites Butterfly tour group who were returning to the UK. Judy and Margaret had been spending a couple of days in Venice and joined Alan at the airport to await the arrival of Wendy who was travelling on the morning British Airways flight from London Gatwick airport. After we had all met up and as we walked to the parking area we identified our first butterfly, an Eastern Bath White. By 11.45am everyone was on board the minibus for the journey to the Dolomites. Our route took us north along the A27 Autostrada. We saw a few birds including Little Egret on a braided riverbed, and Swallows, Swifts and Wood Pigeons before leaving the motorway at Ponte Nelle Alpi. We then drove through Belluno and into the National Park of the Bellunesi Dolomites. -

A Cross-Disciplinary Study of the Work and Collections by Roberto De Visiani (1800–1878)

Sede Amministrativa: Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Scienze Storiche, Geografche e dell’Antichità Corso di Dotorato di Ricerca in Studi Storici, Geografci e Antropologici Curricolo: Geografa Umana e Fisica Ciclo ⅩⅨ A Cross-disciplinary Study of the Work and Collections by Roberto de Visiani (1800–1878) Coordinatore: Ch.ma Prof. Maria Cristina La Rocca Supervisore: Dr. Antonella Miola Dottorando: Moreno Clementi Botany: n. Te science of vegetables—those that are not good to eat, as well as those that are. It deals largely with their fowers, which are commonly badly designed, inartistic in color, and ill-smelling. Ambrose Bierce [1] Table of Contents Preface.......................................................................................................................... 11 1. Introduction.............................................................................................................. 13 1.1 Research Project.......................................................................................................13 1.2 State of the Art.........................................................................................................14 1.2.1 Literature on Visiani 14 1.2.2 Studies at the Herbarium of Padova 15 1.2.3 Exploration of Dalmatia 17 1.2.4 Types 17 1.3 Subjects of Particular Focus..................................................................................17 1.3.1 Works with Josif Pančić 17 1.3.2 Flora Dalmatica 18 1.3.3 Visiani’s Relationship with Massalongo 18 1.4 Historical Context...................................................................................................18 -

(12) United States Plant Patent (10) Patent No.: US PP19,832 P2 Hart (45) Date of Patent: Mar

USOOPP19832P2 (12) United States Plant Patent (10) Patent No.: US PP19,832 P2 Hart (45) Date of Patent: Mar. 17, 2009 (54) HELIANTHEMUM PLANT NAMED (51) Int. Cl. MAXROSS AOIH 5/00 (2006.01) (50) Latin Name: Helianthemum nummularium (52) U.S. Cl. ....................................................... Pt./226 Varietal Denomination: Maxross (58) Field of Classification Search ................... Plt./226, Plt./263,263.1 (76) Inventor: Michael Hart, No. 2 The Cottages, See application file for complete search history. Habberley Road, Worcestershire (GB), DY 121 LA Primary Examiner Kent L Bell (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm Jondle & Associates, P.C. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 (57) ABSTRACT U.S.C. 154(b) by 11 days. A new Helianthemum plant particularly distinguished as a hardy, evergreen, semi-compact and low-growing shrub with (21) Appl. No.: 11/978,294 red-purple flowers and yellow stamens, is disclosed. (22) Filed: Oct. 29, 2007 1 Drawing Sheet 1. 2 Genus and species: Helianthemum nummularium. DESCRIPTION OF THE NEW CULTIVAR Variety denomination: Maxross. The following detailed descriptions set forth the distinc BACKGROUND OF THE NEW PLANT tive characteristics of Maxross. The data which define 5 these characteristics were collected from asexual reproduc The present invention comprises a new and distinct culti tions carried out in Bewdley, Worcestershire, United King var of Helianthemum, botanically known as Helianthemum dom. The plant history was taken on 2 year old plants grown nummularium and hereinafter referred to by the cultivar outdoors. Color readings were taken outdoors under natural name Maxross. The new cultivar was discovered in light. -

Plants Resistant Or Susceptible to Armillaria Mellea, the Oak Root Fungus

Plants Resistant or Susceptible to Armillaria mellea, The Oak Root Fungus Robert D. Raabe Department of Environmental Science and Management University of California , Berkeley Armillaria mellea is a common disease producing fungus found in much of California . It commonly occurs naturally in roots of oaks but does not damage them unless they are weakened by other factors. When oaks are cut down, the fungus moves through the dead wood more rapidly than through living wood and can exist in old roots for many years. It also does this in roots of other infected trees. Infection takes place by roots of susceptible plants coming in contact with roots in which the fungus is active. Some plants are naturally susceptible to being invaded by the fungus. Many plants are resistant to the fungus and though the fungus may infect them, little damage occurs. Such plants, however, if they are weakened in any way may become susceptible and the fungus may kill them. The plants listed here are divided into three groups. Those listed as resistant are rarely damaged by the fungus. Those listed as moderately resistant frequently become infected but rarely are killed by the fungus. Those listed as susceptible are severely infected and usually are killed by the fungus. The fungus is variable in its ability to infect plants and to damage them. Thus in some areas where the fungus occurs, more plant species may be killed than in areas where other strains of the fungus occur. The list is composed of two parts. In Part A, the plants were tested in two ways. -

Helianthemum Sinuspersicum (Cistaceae), a New Woody Species from Iran

©Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien 108 B 303 - 306 Wien, Mai 2007 Helianthemum sinuspersicum (Cistaceae), a new woody species from Iran F. Gholamian* & F. Ghahremaninejad** Zusammenfassung Eine neue Art in der Gattung Helianthemum (Cistaceae) wird beschrieben. Sie ist verholzt, die Stipel fallen ab, die Blütenstiele sind lang und dünn, und sie besitzt 34 - 36 Staubblätter: Helianthemum sinuspersicum. Diese Art ist endemisch im südlichen Iran in der Provinz Bushehr. Sie ist am ähnlichsten und möglicher- weise nahe verwandt mit H. kahiricum DEL., unterscheidet sich aber im generellen Habitus und bei den Blütenstielen. Abstract A new Helianthemum species (Cistaceae), with a woody habit, deciduous stipules, long and thin pedicels, and 34 - 36 stamens is described and illustrated: Helianthemum sinuspersicum. It is endemic to the Bushehr province of southern Iran. The species appears to be most closely related to H. kahiricum DEL., but differs from it especially in pedicel and habit characteristics. Key words: Cistaceae, Helianthemum sinuspersicum, Iran, new species, taxonomy. Introduction The family Cistaceae Juss., with eight genera and nearly 175 species is distributed in temperate and warm climates (MABBERLEY 1997), includes only 9 species in the Flora Iranica region (RECHINGER 1967). These nine species belong to three genera Helianthemun, Fumana, and Cistus. Six non-endemic species of Helianthemum, H. stipulatum (FORSSK.) C.CHRIST., H. lip- pii (L.) PERS., H. nummularium (L.) MILLER, H. ledifolium (L.) MILLER, H. salicifolium (L.) MILLER, and H. aegyptiacum (L.) MILLER, were included in the account of the genus in Flora Iranica (RECHINGER 1967). Five of these species, i.e.