Interview #25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Resurgence of Asa'ib Ahl Al-Haq

December 2012 Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ Photo Credit: Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq protest in Kadhimiya, Baghdad, September 2012. Photo posted on Twitter by Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2012 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2012 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sam Wyer is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, where he focuses on Iraqi security and political matters. Prior to joining ISW, he worked as a Research Intern at AEI’s Critical Threats Project where he researched Iraqi Shi’a militia groups and Iranian proxy strategy. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Middlebury College in Vermont and studied Arabic at Middlebury’s school in Alexandria, Egypt. ABOUT THE INSTITUTE The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. ISW is committed to improving the nation’s ability to execute military operations and respond to emerging threats in order to achieve U.S. -

Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance

Order Code RL31339 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance Updated May 16, 2005 Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance Summary Operation Iraqi Freedom accomplished a long-standing U.S. objective, the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, but replacing his regime with a stable, moderate, democratic political structure has been complicated by a persistent Sunni Arab-led insurgency. The Bush Administration asserts that establishing democracy in Iraq will catalyze the promotion of democracy throughout the Middle East. The desired outcome would also likely prevent Iraq from becoming a sanctuary for terrorists, a key recommendation of the 9/11 Commission report. The Bush Administration asserts that U.S. policy in Iraq is now showing substantial success, demonstrated by January 30, 2005 elections that chose a National Assembly, and progress in building Iraq’s various security forces. The Administration says it expects that the current transition roadmap — including votes on a permanent constitution by October 31, 2005 and for a permanent government by December 15, 2005 — are being implemented. Others believe the insurgency is widespread, as shown by its recent attacks, and that the Iraqi government could not stand on its own were U.S. and allied international forces to withdraw from Iraq. Some U.S. commanders and senior intelligence officials say that some Islamic militants have entered Iraq since Saddam Hussein fell, to fight what they see as a new “jihad” (Islamic war) against the United States. -

Emergency Assessment Displacement Due to Recent Violence (Post 22 Feb 2006) Central and Southern 15 Governorates 24 Dec

EMERGENCY ASSESSMENT DISPLACEMENT DUE TO RECENT VIOLENCE (POST 22 FEB 2006) CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN 15 GOVERNORATES 24 DEC. 2006 REPORT Following are numbers of displaced as per reports received from monitoring partners since 22 February 2006 (details per governorate further below). As displacement is ongoing, please note that this information is constantly changing. No. of Individuals (family No. of number x Origin Displaced to Families 6) Sect Needs Baghdad, Basrah, Thi-Qar, Water, food, shelter, and non-food Kerbala, Missan Anbar 6,607 39,642 Sunni items Shia, and small group Shelter, employment opportunities, Baghdad, Anbar, and Diyala Babylon 3,169 19,014 of Sunni food Shia and Baghdad, Diyala, Anbar, Salah Sunni, al-Din, Kirkuk, Babylon, some Shelter, employment opportunities, Ninewa, Wassit Baghdad 6,651 39,906 Yazidi food Food, shelter, employment Baghdad, Anbar, Salah al-Din Basrah 1,439 8,634 Shia opportunities, legal assistance Baghdad, within Diyala, and Sunni and Shelter, employment opportunities, Salah Al Din Diyala 3,600 21,600 Shia food Tameem, Baghdad, Diyala, Food and non-food items, water, Salah al-Din, Anbar Kerbala 2,060 12,360 Shia shelter, employment opportunities Ninewa, Anbar, Baghdad, Salah al Din, Diyala, Wassit Missan 2,203 13,218 Shia Water,food, and non-food items Baghdad, Anbar, Kiyala, Salah al-Din, Babylon, Wassit Muthanna 950 5,700 Shia Water, shelter, food Baghdad, Anbar, Diyala, Salah al-Din, Ninewa, Babylon, Shelter, employment opportunities, Kirkuk Najaf 2,069 12,414 Shia food Christian, some Sunni Shelter, -

Activity Info Training

Activity Info Training 2021 Shelter Cluster – Iraq sheltercluster.org 1 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 2021 ActivityInfo Database for IDPs and Returnees https://v4.activityinfo.org/ Monitoring & Evaluation software for humanitarian operations Shelter Cluster – Iraq sheltercluster.org 2 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter Training Agenda: 1 Brief about Activity info 2 SNFI forms in 2021 3 SNFI Indicators in 2021 4 Practical session Shelter Cluster – Iraq sheltercluster.org 3 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 1 Brief about new Activity info 2021 Shelter Cluster – Iraq sheltercluster.org 4 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter HRP vs. Non-HRP in 2021 1. Partner's profile: • Partner should be an active participant of the Shelter Cluster at the national, sub- national and/or governorate coordination levels. • Partner should have proven record of consistent reporting in the dedicated platforms (ActivityInfo, the UN-OCHA Financial Tracking Service, and the Shelter Cluster and UN-HABITAT war-damaged shelter reporting tool). • Access to the proposed geographical areas, or the possibility to expand presence with minimum investment are a requirement. 2. Programs’ requirements: • clear approach and methodology used to select beneficiaries, including the socio- economic vulnerability criteria (SEVAT); • in line with the recommendations, technical guidelines and policies developed by the Shelter Cluster. 3. Intervention requirements: • Carried out through priority Shelter and NFI activities in the 46 prioritized districts, will be considered as contributing -

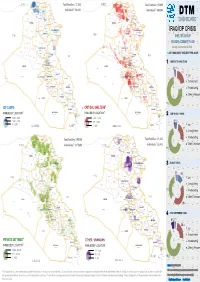

20141214 04 IOM DTM Repor

TURKEY Zakho Amedi Total Families: 27,209 TURKEY Zakho Amedi TURKEY Total Families: 113,999 DAHUK Mergasur DAHUK Mergasur Dahuk Sumel 1 Sumel Dahuk 1 Soran Individual : 163,254 Soran Individuals : 683,994 DTM Al-Shikhan Akre Al-Shikhan Akre Tel afar Choman Telafar Choman Tilkaif Tilkaif Shaqlawa Shaqlawa Al-Hamdaniya Rania Al-Hamdaniya Rania Sinjar Pshdar Sinjar Pshdar ERBIL ERBIL DASHBOARD Erbil Erbil Mosul Koisnjaq Mosul Koisnjaq NINEWA Dokan NINEWA Dokan Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Dabes Dabes IRAQ IDP CRISIS Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Sulaymaniya Sulaymaniya KIRKUK KIRKUK Al-Hawiga Chamchamal Al-Hawiga Chamchamal DarbandihkanHalabja SYRIA Darbandihkan SYRIA Daquq Daquq Halabja SHELTER GROUP Kalar Kalar Baiji Baiji Tooz Tooz BY DISPLACEMENT FLOW Ra'ua Tikrit SYRIA Ra'ua Tikrit Kifri Kifri January to December 9, 2014 SALAH AL-DIN Haditha Haditha SALAH AL-DIN Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Al-Ka'im Al-Ka'im Al-Thethar Al-Khalis Al-Thethar Al-Khalis % OF FAMILIES BY SHELTER TYPE AS OF: DIYALA DIYALA Ana Balad Ana Balad IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Heet Al-Fares Heet Al-Fares Tar m ia Tarm ia Ba'quba Ba'quba Adhamia Baladrooz Adhamia Baladrooz Kadhimia Kadhimia JANUARY TO MAY CRISIS KarkhAl Resafa Ramadi Ramadi KarkhAl Resafa 1 Abu Ghraib Abu Ghraib BAGHDADMada'in BAGHDADMada'in ANBAR Falluja ANBAR Falluja Mahmoudiya Mahmoudiya Badra Badra 2% 1% Al-Azezia Al-Azezia Al-Suwaira Al-Suwaira Al-Musayab Al-Musayab 21% Al-Mahawil -

Three Years of Post-Samarra Displacement in Iraq

IOM EMERGENCY NEEDS ASSESSMENTS FEBRUARY 22, 2009: THREE YEARS OF POST-SAMARRA DISPLACEMENT IN IRAQ I. POPULATION DISPLACEMENT AND RETURN IN IRAQ Three years after a severe wave of sectarian violence began, returns are increasing and new displacement is rare. Iraqis look to rebuilding their lives facing an uncertain security future. On 22 February 2006, the bombing of the Al-Askari Mosque in Samarra triggered escalating sectarian violence that drastically changed the cause and INSIDE: scale of displacement in Iraq, both to locations inside Iraq and to locations Displacement/ 1 abroad. Since February 2006, more than 1,600,000 Iraqis (270,000 Return Summary families) have been displaced - approximately 5.5% of the total Post February 2006 population. Of these 270,000 families, IOM monitoring teams have Profile with identified and assessed 209,402 (an estimated 1,256,412 individuals), or 80% Numbers, 2 of the total post-Samarra displacement population. Identities, Locations, Origins These assessments, illustrated in this report, reveal the demographic Return potentials composition and geographic journeys of the IDP populations remaining in Humanitarian displacement, as well as detail the overwhelming needs for basics such as Needs & Response adequate shelter, sufficient food, clean water, and access to employment. Even as security appears to improve and displacement slows, Iraqi IDPs face threats of eviction and live in precarious environments, with the possibility of violence still a present worry. IOM’s assessments of IDP families’ intentions reveal that many wish to return home and may do so if conditions permit, especially that of security. Others wish to begin new lives in their places of displacement or other locations. -

World Bank Document

Sample Procurement Plan I. General Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan: 2015 2. Date of General Procurement Notice: July, 10, 2015 3. Period covered by this procurement plan: The Project Period II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: Procurement Method Prior Review Threshold Comments US$ 1. ICB and LIB (Goods) Above US$ 1,500,000 All Public Disclosure Authorized 2. NCB (Goods) Above US$ 1,500,000 All 3. ICB (Works) Above US$ 5 million All 4. NCB (Works) Above US$ 5 million All 5. (Non-Consultant Services) Below US$ 1,500,000 All [Add other methods if necessary] 2. Prequalification. Bidders for _Not applicable_ shall be prequalified in accordance with the provisions of paragraphs 2.9 and 2.10 of the Guideline 4. Any Other Special Procurement Arrangements: Given the prevailing impact of the Public Disclosure Authorized ISIS conflict on Iraq, and need to address the urgent and developing requirements, procurement is being processed under paragraph 20 of OP 11.00 “Procurement under Situations of Urgent Need of Assistance or Capacity Constraints”, where “Simplified Procurement Procedures” may apply in accordance with paragraph 12 of the Bank OP 10.00 for investment project financing33. Procurement activities of this Project will include goods, works and both non- consultancy and consultant services under different Components. As they are identified, the activities will be packaged and finalized. 4. Summary of the Procurement Packages planned during the first 18 months after project effectiveness ( including those that are subject to retroactive financing and advanced procurement) Refer to the Procurement Plan Public Disclosure Authorized III. -

Iraq Master List Report 114 January – February 2020

MASTER LIST REPORT 114 IRAQ MASTER LIST REPORT 114 JANUARY – FEBRUARY 2020 HIGHLIGHTS IDP individuals 4,660,404 Returnee individuals 4,211,982 4,596,450 3,511,602 3,343,776 3,030,006 2,536,734 2,317,698 1,744,980 1,495,962 1,399,170 557,400 1,414,632 443,124 116,850 Apr Jun Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Figure 1. Number of IDPs and returnees over time Data collection for Round 114 took place during the months of January were secondary, with 5,910 individuals moving between locations of and February 2020. As of 29 February 2020, DTM identified 4,660,404 displacement, including 228 individuals who arrived from camps and 2,046 returnees (776,734 households) across 8 governorates, 38 districts and individuals who were re-displaced after returning. 2,574 individuals were 1,956 locations. An additional 63,954 returnees were recorded during displaced from their areas of origin for the first time. Most of them fled data collection for Report 114, which is significantly lower than the from Baghdad and Diyala governorates due to ongoing demonstrations, number of new returnees in the previous round (135,642 new returnees the worsening security situation, lack of services and lack of employment in Report 113). Most returned to the governorates of Anbar (26,016), opportunities. Ninewa (19,404) and Salah al-Din (5,754). -

Syria Iran Turkey Jordan

Note on administrative geography data: Mardin Turkey Sanhurfa The pcodes shown on this map use the Common Operational Turkey Dataset (COD) for July 2014. This uses the '109 districts' admin Sindi Syria Zakho Iran Zakho file and the revised pcoding system where IQ-Gxx are governorate IQ-D051 Amedi !\ IQ-D048 Amedi codes and IQ-Dxxx are districts. Kule Jordan Sarsink Mergasur Sherwan Mazn Kuwait Dahuk IQ-D067 IQ-D049 Zawita Khalifan Sumel Saudi Arabia IQ-D050 Mergasur Lower Soran Sidakan Fayda Akre Alqosh Akre IQ-D069 Ain Sifne IQ-D083 Choman Telafar Soran Haji Omaran IQ-D090 Tilkaif Shikhan IQ-D063 IQ-D091 IQ-D088 Rawanduz Al-Hasakah Choman [1] Wana BarazanHarir Iran Tilkef Bashiqa Shaqlawa IQ-D068 Talafar Shaqlawa Salahaddin Sinjar Bartalah Betwata Sinjar Hamdaniya IQ-D089 o Al Hamdaniyah Rania IQ-D085 Ranya Ainkawa IQ-D031 o Chwarqurna Hamam al `Alil Bnaslawa Big Pshdar IQ-D030 Ar Raqqah Erbil Koysinjaq Mosul IQ-D064 Bngrd IQ-D087 Khalakan Shura Qushtappa Big Koisnjaq IQ-D065 Dokan IQ-D026 Taqtaq Mawat Dibaga Surdash Al Qayyarah Makhmur Altun Kupri Makhmur Aghjalar o Sharbazher Garmk IQ-D066 IQ-D032 Dibs Penjwin IQ-D029 Penjwin Ba'aj Hatra Dabes IQ-D073 IQ-D084 Chamchamal Bakrajo Syria Hatra Shirqat Sulaymaniya Dayr az Zawr IQ-D033 IQ-D086 IQ-D106 Kirkuk IQ-D076 Chamchamal Haweeja IQ-D024 Qaradagh Ar Riyad Tazakhurmatu Sangaw Halabja Khurmal Dukaro IQ-D027 Hawiga IQ-D075 Darbandihkan Halabja IQ-D025 Daquq Darbandikhan o IQ-D074 Bayji o Touz Hourmato Kalar Baiji IQ-D028 Tilako Big IQ-D101 Tooz Sulaiman Bag IQ-D109 Ru'ua -

Investment Map of Iraq 2016

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investment Map of Iraq 2016 Dear investor: Investment opportunities found in Iraq today vary in terms of type, size, scope, sector, and purpose. the door is wide open for all investors who wish to hold investment projects in Iraq,; projects that would meet the growing needs of the Iraqi population in different sectors. Iraq is a country that brims with potential, it is characterized by its strategic location, at the center of world trade routes giving it a significant feature along with being a rich country where I herby invite you to look at Iraq you can find great potentials and as one of the most important untapped natural resources which would places where untapped investment certainly contribute in creating the decent opportunities are available in living standards for people. Such features various fields and where each and characteristics creates favorable opportunities that will attract investors, sector has a crucial need for suppliers, transporters, developers, investment. Think about the great producers, manufactures, and financiers, potentials and the markets of the who will find a lot of means which are neighboring countries. Moreover, conducive to holding new projects, think about our real desire to developing markets and boosting receive and welcome you in Iraq , business relationships of mutual benefit. In this map, we provide a detailed we are more than ready to overview about Iraq, and an outline about cooperate with you In order to each governorate including certain overcome any obstacle we may information on each sector. In addition, face. -

Iraq Missile Chronology

Iraq Missile Chronology 2008-2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003-2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1992 | 1991 Last update: November 2008 As of November 2008, this chronology is no longer being updated. For current developments, please see the Iraq Missile Overview. 2008-2006 29 February 2008 UNMOVIC is officially closed down as directed by UN Security Council Resolution 1762, which terminated its mandate. [Note: See NTI Chronology 29 June 2007]. —UN Security Council, "Iraq (UNMOVIC)," Security Council Report, Update Report No. 10, 26 June 2008. 25 September 2007 U.S. spokesman Rear Admiral Mark Fox claims that Iranian-supplied surface-to-air missiles, such as the Misagh 1, have been found in Iraq. The U.S. military says that these missiles have been smuggled into Iraq from Iran. Iran denies the allegation. [Note: See NTI Chronology 11 and 12 February 2007]. "Tehran blasted on Iraq Missiles," Hobart Mercury, 25 September 2007, in Lexis-Nexis Academic Universe; David C Isby, "U.S. Outlines Iranian Cross-Border Supply of Rockets and Missiles to Iraq," Jane's Missiles & Rockets, Jane's Information Group, 1 November 2007. 29 June 2007 The Security Council passes Resolution 1762 terminating the mandates of the UN Monitoring, Verification, and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) and the IAEA in Iraq. Resolution 1762 also requests the UN Secretary General to dispose safely of archives containing sensitive information, and to transfer any remaining UNMOVIC funds to the Development Fund for Iraq. A letter to the Security Council from the Iraqi government indicates it is committed to respecting its obligations to the nonproliferation regime. -

IRAQ: Camp Closure Status Date: 14 January 2021

IRAQ: Camp Closure Status Date: 14 January 2021 Date of Departures Site closed Governorate District Site Name 1 Site Type Population3 closure/change 2 (ind.) TURKEY Under closure Al-Sulaymaniyah Al-Sulaymaniyah Ashti IDP Camp No closure announced* 8,865 Closure paused Al-Sulaymaniyah Kalar Tazade Camp No closure announced* 1,031 Zakho No closure announced Baghdad Al-Mahmoudiya Latifiya 1**** Camp No closure announced* 126 Camp population Baghdad Al-Mahmoudiya Latifiya 2**** Camp No closure announced* 58 Duhok Al-Amadiya Dawadia Camp No closure announced* 2,577 Al-Amadiya 22,583 Sumail Al-Zibar Duhok Sumail Bajet Kandala Camp No closure announced* 8,549 10,000 Duhok Sumail Rwanga Community Camp No closure announced* 12,759 Duhok Sumail Kabarto 2 Camp No closure announced* 11,120 Aqra Rawanduz 2,500 Telafar Duhok Sumail Khanke Camp No closure announced* 14,210 Tilkaef Duhok Sumail Shariya Camp No closure announced* 15,217 Al-Shikhan Shaqlawa Duhok Sumail Kabarto 1 Camp No closure announced* 11,873 Al-Hamdaniya Duhok Zakho Berseve 1 Camp No closure announced* 5,712 Sinjar Erbil Rania Pshdar Duhok Zakho Berseve 2 Camp No closure announced* 7,126 Khazer Camp Hamam Al Ali 2 Camp Duhok Zakho Chamishku Camp No closure announced* 22,583 Erbil Al-Mosul Duhok Zakho Darkar Camp No closure announced* 3,358 Al Salamyiah Camp Qayyarah-Jad’ah 5 Camp Koysinjaq Erbil Erbil Baharka Camp No closure announced* 4,528 Dokan Sharbazher Erbil Erbil Harshm Camp No closure announced* 1,434 Qayyarah-Jad’ah 1 Camp Panjwin Erbil Makhmour Debaga 1 Camp No closure announced*