Handbook to Life in Renaissance Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moma's Folk Art Museum and DS+R Scandal 14

017 Index MoMA's Folk Art Museum and DS+R 01 Editor´s Note Scandal 14 A Brief History of 02 Gabriela Salazar’s!In Advance Artwork Commission 22 of a Storm!Art Book Top Commissioned Promotion 26 Art Pieces by Top Commissioners of All Time 08 27 Contact Editor´s note Who were the first patrons in the history of art to commissioning artwork and what was their purpose? How has commissioning changed for the artist and for the entity requesting the art piece? What can be predicted as the future of the commissioning world? Our May issue explores the many and different ramifications of art commission in the past and in the present. Historical facts and recent scandals can make a quirky encapsulation of what is like to be commissioned to do art; to be commissioned an art piece for an individual, business, or government can sometimes be compared to making an agreement with the devil. “Commissioned artwork can be anything: a portrait, a wedding gift, artwork for a hotel, etc. Unfortunately, there are no universal rules for art commissions. Consequently, many clients take advantage of artists,” says Clara Lieu, an art critic for the Division of Experimental and Foundation studies and a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design. This issues aims to track down the history of ancient civilizations and the Renaissance in its relation to commissioned work, and its present manifestations in within political quarrels of 01 respectable art institutions. A Brief History of Artwork Commission: Ancient Rome and the Italian Renaissance An artwork commission is the act of soliciting the creation of an original piece, often on behalf of another. -

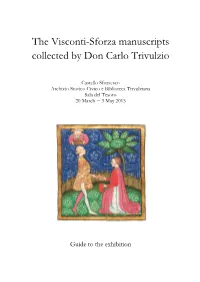

The Visconti-Sforza Manuscripts Collected by Don Carlo Trivulzio

The Visconti-Sforza manuscripts collected by Don Carlo Trivulzio Castello Sforzesco Archivio Storico Civico e Biblioteca Trivulziana Sala del Tesoro 20 March ~ 3 May 2015 Guide to the exhibition I manoscritti visconteo sforzeschi di don Carlo Trivulzio Una pagina illustre di collezionismo librario nella Milano del Settecento Milano · Castello Sforzesco Archivio Storico Civico e Biblioteca Trivulziana · Sala del Tesoro 20 marzo ~ 3 maggio 2015 Sindaco Mostra a cura di Giuliano Pisapia Isabella Fiorentini, Marzia Pontone Assessore alla Cultura Testi di Filippo Del Corno Marzia Pontone Direttore Centrale Cultura Redazione e revisione Giuliana Amato Loredana Minenna Direttore Settore Soprintendenza Castello, Manutenzione conservativa Musei Archeologici e Musei Storici Stefano Dalla Via Claudio Salsi Segreteria amministrativa Ufficio Stampa Luca Devecchi Elena Conenna Coordinamento logistico e sicurezza Luigi Spinelli Allestimenti CSC Media Soprintendente Castello Sforzesco Claudio Salsi Traduzioni Promoest Srl – Ufficio Traduzioni Milano Responsabile Servizio Castello Giovanna Mori Fotografie Comunicazione Officina dell’immagine, Luca Postini Maria Grazia Basile Saporetti Immagini d’arte Colomba Agricola Servizio di custodia Corpo di Guardia del Castello Sforzesco Archivio Storico Civico Biblioteca Trivulziana Si ringraziano Rachele Autieri, Lucia Baratti, Piera Briani, Mariella Chiello, Civica Stamperia, Ilaria De Palma, Funzionario Responsabile Benedetta Gallizia di Vergano, Isabella Fiorentini Maria Leonarda Iacovelli, Arlex Mastrototaro, -

Pirani-Sforza E Le Marche.Pdf

Francesco Pirani SUNT PICENTES NATURA MOBILES NOVISQUE STUDENTES. FRANCESCO SFORZA E LE CITTÀ DELLA MARCA DI ANCONA (1433-1447) «In the march of Ancona, Sforza ruled without any reference the Pope and paying little attention to his subjects except for the money he could squeeze out of them. Sforza perhaps did not intend to use the march for more than a reserve of men, money and victuals, though it is doubtful if his depredations were different in kind from those of papal governors» 1. Il giudizio un po’ liquidatorio di un grande storico dello Stato della Chiesa, Peter Partner, mostra appieno la ragione per cui l’espe- rienza di potere di Francesco Sforza nelle Marche sia stata derubrica- ta nella storiografia novecentesca a una breve parentesi o a una tem- poranea anomalia rispetto ai più rilevanti sviluppi della monarchia pontificia. Quella dello Sforza, in breve, sarebbe stata una domina- zione meramente militare, basata sul prelievo forzoso di risorse finan- ziarie e umane, cioè di uomini destinati a combattere in tutta l’Italia nelle milizie capitanate dall’abile condottiero di origine romagnola. Del resto, in questi anni le Marche vissero di luce riflessa rispetto a quanto si andava decantando nei maggiori stati regionali della Peni- sola e le sue sorti politiche dipesero più da decisioni prese altrove (a Roma, a Firenze o a Milano) che non da fattori endogeni. In linea generale è indubbio che nel primo Quattrocento le condotte militari, oltre ad assicurare consistenti guadagni per chi le gestiva, servivano a stabilire un raccordo con le forze territoriali più potenti della Peniso- la: i piccoli stati governati da principi-condottieri, come quello dei Montefeltro fra Romagna e Marche, seppero trarre infatti enormi vantaggi proprio dalla capacità di istaurare “un rapporto di dipen- denza, o meglio, di simbiosi polivalente con le formazioni statali più potenti” d’Italia 2. -

Tom XV 5 CIECIELĄG 2008: 99–101

THE TEMPLE ON THE COINS OF BAR KOKHBA – A MANIFESTATION OF LONGING… which is undoubtedly an expression of the rebels’ hope and goals, i.e. the rebuilding of the Jerusalem temple, restoration of circumcision and regaining independence, is important. It is worth noting here, however, that perhaps we are not dealing here so much with a political programme, but rather with reconciliation with God and eternal salvation, which would link the revolt of Bar Kokhba with the ideology of the first revolt against the Romans and with the Hasmonean period.4 Equally important, or perhaps even more important, is the inscription referring to Jerusalem (on the coins from the first year of revolt), inseparably connected with Hadrian’s decision to transform the city into a Roman colony under the name Colonia Aelia Capitolina and probably also with the refusal to rebuild the Temple.5 As we are once again dealing here with a manifestation of one of the most important goals of Bar Kokhba and the insurgents – the liberation of Jerusalem and the restoration of worship on the Temple Mount. Even more eloquent is the inscription on coins minted in the third year of the revolt: Freedom of Jerusalem, indicating probably a gradual loss of hope of regaining the capital and chasing the Romans away. Many researchers believed that in the early period of the revolt, Jerusalem was conquered by rebels,6 which is unlikely but cannot be entirely excluded. There was even a hypothesis that Bar Kokhba rebuilt the Temple of Jerusalem, but he had to leave Jerusalem, which he could -

Bollettino Di Numismatica on Line Materiali N. 42-2016

Bollettino di Numismatica online - Materiali 42 Collezione di Vittorio Emanuele III – La zecca di Milano (1450-1468) SOPRINTENDENZA SPECIALE PER IL COLOSSEO, IL MUSEO NAZIONALE ROMANO E L’AREA ARCHEOLOGICA DI ROMA Medagliere LA COLLEZIONE DI VITTORIO EMANUELE III collana on line a cura di Silvana BalBi de Caro GaBriella anGeli Bufalini Si ringrazia la Società Numismatica Italiana per la collaborazione scientifica alla realizzazione del presente fascicolo sulla zecca di Milano Ministero............................................................................................................................... dei beni e delle attività culturali..................................................... e del turismo BOLLETTINO DI NUMISMATICA ON-LINE MATERIALI Numero 42 – Giugno 2016 ROMA, MUSEO NAZIONALE ROMANO LA COLLEZIONE DI VITTORIO EMANUELE III La zecca di MiLano Da Francesco Sforza (1450-1466) a Bianca Maria Visconti e Galeazzo Maria Sforza (1466-1468) di Alessandro Toffanin Sommario la zecca di Milano. Da Francesco Sforza (1450-1466) a Bianca Maria Visconti e Galeazzo Maria Sforza (1466-1468) Il contesto storico . p . 5 I materiali . » 6 Le grida monetarie . » 8 Francesco Sforza, duca di Milano (1450-1466) (cat . nn . 1081-1214) . » 9 Le monete di Francesco Sforza . » 9 Ducati in oro . » 9 Moneta grossa . » 10 Quindicini, soldini, sesini e cinquine . » 11 Trilline . » 12 Denari . » 12 Medaglie (multipli in oro e argento) . » 12 Bianca Maria Visconti e Galeazzo Maria Sforza, duchi di Milano (1466-1468) (cat . nn . 1215-1258) . » 14 Note -

Ducks and Deer, Profit and Pleasure: Hunters, Game and the Natural Landscapes of Medieval Italy Cristina Arrigoni Martelli A

DUCKS AND DEER, PROFIT AND PLEASURE: HUNTERS, GAME AND THE NATURAL LANDSCAPES OF MEDIEVAL ITALY CRISTINA ARRIGONI MARTELLI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO ONTARIO May 2015 © Cristina Arrigoni Martelli, 2015 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is an ample and thorough assessment of hunting in late medieval and Renaissance northern and central Italy. Hunting took place in a variety of landscapes and invested animal species. Both of these had been influenced by human activities for centuries. Hunting had deep cultural significance for a range of social groups, each of which had different expectations and limitations on their use of their local game animal-habitat complexes. Hunting in medieval Italy was business, as well as recreation. The motivations and hunting dynamics (techniques) of different groups of hunters were closely interconnected. This mutuality is central to understanding hunting. It also deeply affected consumption, the ultimate reason behind hunting. In all cases, although hunting was a marginal activity, it did not stand in isolation from other activities of resource extraction. Actual practice at all levels was framed by socio-economic and legal frameworks. While some hunters were bound by these frameworks, others attempted to operate as if they did not matter. This resulted in the co-existence and sometimes competition, between several different hunts and established different sets of knowledge and ways to think about game animals and the natural. The present work traces game animals from their habitats to the dinner table through the material practices and cultural interpretation of a variety of social actors to offer an original survey of the topic. -

TIMELINE 1388 Giangaleazzo Visconti's Testament Bequeaths

TIMELINE YEAR DATE EVENT 1388 Giangaleazzo Visconti’s testament bequeaths Milan to his sons or—if they should all die—to his daughter Valentina 1395 11 May Emperor Wenceslaus creates Duchy of Milan for Giangaleazzo 1396 13 October Emperor Wenceslaus extends Duchy of Milan in second investiture 1447 18 August Ambrosian Republic declared 1450 26 February Francesco I Sforza assumes control of Duchy of Milan 1466 8 March Francesco I Sforza dies; his son Galeazzo Maria becomes duke 1476 26 December Galeazzo Maria Sforza assassinated 1480 7 October Ludovico Sforza assumes nominal control of duchy 1494 September King Charles VIII invades Italy 1495 26 March Maximilian I invests Ludovico Sforza with Duchy of Milan 6 July Battle of Fornovo 1499 2 September Ludovico flees Milan; city and duchy surrender to France 1500 27 January Pro- Sforza insurrection; Ludovico’s restoration 10 April Battle of Novara; Ludovico captured; Milan returns to French control 1502 July- August Louis XII visits Lombardy ix x TIMELINE 1505 7 April Haguenau Conference— Maximilian I invests Louis XII with Duchy of Milan 1506 June Genoa revolts against French rule 1507 April- May Louis XII puts down Genoese revolt; visits Milan 1509 14 May Battle of Agnadello 14 June Maximilian I re- invests Louis XII with Duchy of Milan 1511 2 November Council of Pisa- Milan against Julius II opens 1512 11 April Battle of Ravenna; French rule of Milan begins to crumble 21 April Council of Pisa- Milan declares Julius II deposed; Julius opens Fifth Lateran Council 12 August Massimiliano -

Arme E Imprese Viscontee Sforzesche Ms. Trivulziano N. 1390 (2A Parte)

Arme e imprese viscontee sforzesche Ms. Trivulziano n. 1390 (2a parte) Autor(en): Maspoli, Carlo Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Archives héraldiques suisses = Schweizer Archiv für Heraldik = Archivio araldico svizzero : Archivum heraldicum Band (Jahr): 111 (1997) Heft 1 PDF erstellt am: 05.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-745770 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Arme e imprese viscontee sforzesche Ms. Trivulziano n. 1390 (2a parte) Carlo Maspoli p. 5 (c) d'oro, a tre aquile di nero, linguate di rosso, Dominus, dominus Filipus Maria coronate del campo, poste l'una sopra Vicecomes, comes Papie Paîtra2. -

SFORZA, Tristano Di Maria Nadia Covini - Dizionario Biografico Degli Italiani - Volume 92 (2018)

SFORZA, Tristano di Maria Nadia Covini - Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 92 (2018) SFORZA, Tristano. – Nacque a Milano ai primi di luglio del 1429 da Francesco Sforza futuro duca di Milano, che a quel tempo militava per il duca Filippo Maria Visconti, ma era stato messo da parte e per alcuni anni ridotto forzatamente all’ozio. Francesco Sforza conviveva con Giovanna da Acquapendente, che gli aveva dato alcuni figli, ma Tristano ebbe per madre, come scrisse Nicodemo Tranchedini (Parodi, 1920, p. 339), la «concubina di Morello Scolari di Parma», squadrero del duca di Milano e signore di un piccolo castello piacentino. Fino al 1443 Tristano fu allevato nella casa milanese di Scolari e della moglie Dorotea della Croce in porta Vercellina. Pur se impegnato nelle imprese militari, Francesco Sforza non mancò di assicurargli un’educazione distinta e dal 1439 lo fece seguire negli studi dall’umanista Mattia da Trivio, che poi divenne maestro anche di Sforza Secondo, nato da Giovanna da Acquapendente. Il 16 ottobre 1448 Francesco Sforza, già sposo di Bianca Maria Visconti e padre di nuova prole ‘legittima’, ottenne da papa Nicolò V la legittimazione di Tristano e di tutti i figli e le figlie naturali. A differenza di Sforza Secondo, spesso disobbediente al padre, Tristano fu un figlio devoto e seguì le orme paterne. Giovanissimo armorum ductor, a capo di un manipolo di lance di cavalleria, già nel 1447 militava nella compagnia sforzesca; dopo un periodo trascorso a Cremona prese le stanze a Piacenza e nel 1448 partecipò alla battaglia di Caravaggio e alle operazioni militari contro i veneziani. -

SFORZA Sforza Sec. XV 1535 Famiglia Signoria Poi Ducato Di

DENOMINAZIONE SFORZA ALTRE DENOMINAZIONI DENOMINAZIONE IN GUIDA Sforza GENERALE DATA INIZIO Sec. XV DATA FINE 1535 TIPOLOGIA SOGGETTO Famiglia PRODUTTORE CONTESTO STATUALE Signoria poi Ducato di Milano (1317-1535) STORIA Famiglia che deve il suo nome a Muzio Attendolo, condottiero e, dal 1411, conte di Cotignola (Ravenna). Egli iniziò la propria carriera militare nella compagnia di ventura di Alberico da Barbiano, che lo soprannominò ‘Sforza’ per la sua prestanza fisica. Suo figlio Francesco (1401-1466), nato da una relazione con Lucia di Torsciano, giovanissimo seguì le sue orme, divenne capitano e sposò Polissena, figlia di Carlo Ruffo (conte di Montalto, in provincia di Cosenza), che però morì qualche anno dopo, come la loro bambina. Padre e figlio riconquistarono Napoli per la regina Giovanna, combattendo contro Alfonso d’Aragona. Alla morte di Muzio, Francesco, già dichiarato legittimo, ereditò le signorie su Toscanella e Acquapendente, in provincia di Viterbo, e le dignità e i privilegi concessi al padre. Inoltre la regina Giovanna dispose che Francesco e i suoi discendenti assumessero come cognome il soprannome del capitano defunto, Sforza. Francesco passò a servizio di Filippo Maria Visconti, a capo delle truppe milanesi, con Niccolò Piccinino e Niccolò da Tolentino. Quando quest’ultimo disertò, per rafforzare il legame con Francesco, Filippo Maria gli promise in sposa la figlia naturale (poi legittimata) Bianca Maria e gli concesse alcuni feudi. Francesco fu inviato nello Stato Pontificio, dove occupò la Marca d’Ancona e alcuni territori in Umbria. Messo alle strette, papa Eugenio IV lo nominò marchese perpetuo di Fermo (nelle Marche), vicario per cinque anni di Todi (Perugia), Gualdo (Macerata) Toscanella e Rispampani, nel viterbese, nonché gonfaloniere della Chiesa. -

Frontmatter 1..14

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01012-3 - The Italian Renaissance State Edited by Andrea Gamberini and Isabella Lazzarini Index More information Index Abruzzi, kingdom of Naples 44 agriculture absolutism Florentine state 448 rise of 305 Naples 39, 44 theorised 321 Sardinia 51 Acaia, principality of 177n, 194 Sicily 9, 17 Acciaiuoli, Angelo 97 southern Italy 16 Acciaiuoli, Niccolo` 31 Alago´n, Leonardo, revolt in Sardinia Acciaiuoli family, Florentine bankers 31 (1478) 62 Acqui, episcopal city 182 Alagona, Artale I, vicar of Sicily 20 Adige League (1407) 211 Alagona family, Catania 257 administrative records 5, 381, 385–405 Alba, acquisition by Milan 157 thirteenth-century communes 387–9 Albert II, duke of Austria 206, 208 nineteenth- and twentieth-century Alberti, Leon Battista 98, 420 archives 386–7 Alberto, count of Gorizia and Trent 198 archiving of 397 Albizi, Maso degli, Florence 93 foreign and diplomatic 399–401, 426–7, Albizi, Rinaldo degli 93, 96, 382 433 on diplomacy 438, 440 and intensification of bureaucracy 401 Albornoz, Gil de, cardinal legate 71, 243, later treatment of 404–5 471 Naples 37, 49 Constitutiones Aegidianae (1357) 73 physical characteristics 392 historiographical view of 71 Piedmont 187 and use of apostolic vicariates 84 political language in 422 Aldobrandeschi family 289, 325 private citizens’ 389, 390 Aleramo, marquis 177 registers 392, 399 Alessandria rural communities 277 acquisition by Milan 157 Savoy 189 factions 311 scattered 403 Ghibellinism in 314 small states and rural communities Alexander VI, pope (Rodrigo Borgia) 84, 401–4 474 in subject towns 390–1 on French invasion 438 see also archives and Roman aristocracy 82 Adorno, Antoniotto, doge of Genoa Alfonso II of Aragon, king of Naples, 226 abdication (1495) 33 Adorno, Giorgio, doge of Genoa 226 Alfonso III of Aragon (d. -

Oration ''Habuisti Dilecta Filia'' of Pope Pius II (28 May 1459, Mantua). Translated by Michael V. Cotta-Schönb

Oration ”Habuisti dilecta filia” of Pope Pius II (28 May 1459, Mantua). Translated by Michael v. Cotta-Schönberg. 5th version. (Orations of Enea Silvio Piccolomini / Pope Pius II; 42) Michael Cotta-Schønberg To cite this version: Michael Cotta-Schønberg. Oration ”Habuisti dilecta filia” of Pope Pius II (28 May 1459, Mantua). Translated by Michael v. Cotta-Schönberg. 5th version. (Orations of Enea Silvio Piccolomini / Pope Pius II; 42). 2019. hal-01223888 HAL Id: hal-01223888 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01223888 Submitted on 7 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. (Orations of Enea Silvio Piccolomini / Pope Pius II; 42) 0 Oration ”Habuisti dilecta filia” of Pope Pius II (28 May 1459, Mantua). Translated by Michael von. Cotta- Schönberg. 5th version 2019 1 Abstract On 27 May 1459, Pope Pius II arrived in Mantua where he was to consult with representatives of the European princes on a crusade against the Turks. The pope was met among others by representatives of the family of Duke Francesco Sforza of Milan whose daughter, the 13 year old Ippolita, gave a charming speech to the pope, to which the pope responded kindly – and very briefly – with the “Habuisti dilecta filia”.