Brock on Curran, 'Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Peace Churches People

The Consistent Life Ethic the vulnerable to only some groups of Mennonite: From Article 22 of the and the Historic Peace Churches people. Some care for the children in the Mennonite Confession of Faith - womb, children recently born with Mennonites, the Church of the Brethren, and disabilities, and the vulnerable among the ill. “Led by the Spirit, and beginning in the the Religious Society of Friends, which Yet they are not as clear about the problems church, we witness to all people that cooperated together in the "New Call to of war or the death penalty or policies that violence is not the will of God. We witness Peacemaking" project, have centuries of could help solve the problems of poverty against all forms of violence, including war experience in the insights of pacifism. This that threaten the very groups they assert among nations, hostility among races and is the understanding that violence is not protection for. They weaken their case by classes, abuse of children and women, ethical, nor is the apathy or cowardice that their inconsistency. Others are very sensitive violence between men and women, abortion, supports violence by others. Furthermore, to the problems of war and the death penalty and capital punishment.” the appearance of violence as a quick fix to and poverty while using euphemisms to problems is deceptive. Through hardened Brethren: From Pastor Wesley Brubaker, avoid the realities of feticide and infanticide, http://www.brfwitness.org/?p=390 hearts, lost opportunities, and over- and allowing the "right to die" become the simplified thinking, violence generally leads "duty to die" in a society still infested with “We seem to realize instinctively that to more problems and often exacerbates far too many prejudices against the abortion is gruesome. -

Just the Police Function, Then a Response to “The Gospel Or a Glock?”

Just the Police Function, Then A Response to “The Gospel or a Glock?” Gerald W. Schlabach Introduction Consider this thought experiment: Adam and Eve have not yet sinned. In fact, they will not sin for a few decades and have begun their family. It is time for supper, but little Cain and his brother Abel are distracted. They bear no ill will, but their favorite pets, the lion and lamb, are particularly cute as they frolic together this afternoon. So Adam goes to find and hurry them home. With nary an unkind word and certainly no violence, he polices their behavior and orders their community life. For like every social arrangement, even this still-altogether-faithful community requires the police function too. A pacifist who does not recognize this point is likely to misconstrue everything I have written about “just policing.”1 Having lived a vocation for mediating between polarized Christian communities since my years in war- torn Central America, I expected a measure of misunderstanding when I proposed the agenda of just policing as a way to move ecumenical dialogue forward between pacifist and just war Christians, especially Mennonites and Catholics. Whoever seeks to engage the estranged in conversation simultaneously on multiple fronts will take such a risk.2 Deeply held identities are often at stake, and as much as the mediator may do to respect community boundaries, he or she can hardly help but threaten them simply by crossing back and forth. The risk of misunderstanding comes with the liminal territory, and nothing but a doggedly hopeful patience for continued conversation will minimize it. -

An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide

AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 1 2Prakrit Bharati academy,An Ahimsa Crisis: Jai YouP Decideur Prakrit Bharati Pushpa - 356 AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 3 Publisher: * D.R. Mehta Founder & Chief Patron Prakrit Bharati Academy, 13-A, Main Malviya Nagar, Jaipur - 302017 Phone: 0141 - 2524827, 2520230 E-mail : [email protected] * First Edition 2016 * ISBN No. 978-93-81571-62-0 * © Author * Price : 700/- 10 $ * Computerisation: Prakrit Bharati Academy, Jaipur * Printed at: Sankhla Printers Vinayak Shikhar Shivbadi Road, Bikaner 334003 An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 4by Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide Contents Dedication 11 Publishers Note 12 Preface 14 Acknowledgement 18 About the Author 19 Apologies 22 I am honored 23 Foreword by Glenn D. Paige 24 Foreword by Gary Francione 26 Foreword by Philip Clayton 37 Meanings of Some Hindi & Prakrit Words Used Here 42 Why this book? 45 An overview of ahimsa 54 Jainism: a living tradition 55 The connection between ahimsa and Jainism 58 What differentiates a Jain from a non-Jain? 60 Four stages of karmas 62 History of ahimsa 69 The basis of ahimsa in Jainism 73 The two types of ahimsa 76 The three ways to commit himsa 77 The classifications of himsa 80 The intensity, degrees, and level of inflow of karmas due 82 to himsa The broad landscape of himsa 86 The minimum Jain code of conduct 90 Traits of an ahimsak 90 The net benefits of observing ahimsa 91 Who am I? 91 Jain scriptures on ahimsa 91 Jain prayers and thoughts 93 -

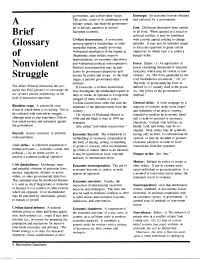

A Brief Glossary of Nonviolent Struggle

government, and subvert their troops. Embargo: An economic boycott initiated This policy, alone or in combination with and enforced by a government. A military means, has received governmen- tal or military attention in several Fast: Deliberate abstention from certain European countries. or all food. When applied in a social or Brief political conflict, it may be combined Civilian insurrection: A nonviolent with a moral appeal seeking to change Glossary uprising against a dictatorship, or other attitudes. It may also be intended simply unpopular regime, usually involving to force the opponent to grant certain widespread repudiation of the regime as objectives, in which case it is called a of illegitimate, mass strikes, massive hunger strike. demonstrations, an economic shut-down, and widespread political noncooperation. Force: Either: (1) An application of Nonviolent Political noncooperation may include power (including threatened or imposed action by government employees and sanctions, which may be violent or non- Struggle mutiny by police and troops. In the final violent). As, "the force generated by the stages, a parallel government often civil disobedience movement." Or: (2) emerges. The body or group applying force as The Albert Einstein Institution has pre- If successful, a civilian insurrection defined in (1), usually used in the plural. pared this brief glossary to encourage the may disintegrate the established regime in As, "the forces at the government's use of more precise terminology in the days or weeks, as opposed to a long-term disposal." field of nonviolent sanctions. struggle of many months or years. Civilian insurrections often end with the General strike: A work stoppage by a Bloodless coup: A successful coup departure of the deposed rulers from the majority of workers in the more impor- d'etat in which there is no killing. -

The Cult of Liberation: the Berkeley Free Church and the Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 Volume 1

Dominican Scholar Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship Faculty and Staff Scholarship 1977 The Cult of Liberation: The Berkeley Free Church and The Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 volume 1 Harlan Stelmach Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies, Dominican University of California, [email protected] Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Stelmach, Harlan, "The Cult of Liberation: The Berkeley Free Church and The Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 volume 1" (1977). Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship. 52. https://scholar.dominican.edu/all-faculty/52 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Staff Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1977 HARLAN DOUGLAS ANTHONY STELMACH ALL RIGHTS RESERVED : TlIE CULT OF LIIiER.'i.TION THE SEPKELEY FREE CHURCH and THE RADICAL CHURCH MOVEMENT 1967-1972 A dissertiatlon by Harlan Douglas Anthony _S_tein)ach presented to Tae Faculty of the Graduate Theological Union in partial fulfillment of the requirenents for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Berkeley, California May 15, 1977 Committee Signatures: Co-Coordjnator ^ y^oV^K- t\M^ Co-Coordinator f 'il -7^ ^- With special thanks to all those who have been part of the process which helped to shape me and this dissertation: MADELYN Joy Aiiy Anne Megan Linda P. ***** Tony Fred G. John M. Edie Bill Jon Joe H. Nancy Gordon Suzanne J. Bob D. Marilena Hugh Sergio Bob C. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Abhidharma, 143 atonement theory/soteriology (how Jesus’ Abraham, 13, 85 death saved humanity), 54 Abu Talib, 10 Augustine, 57–8, 69, 81 Acts of the Apostles, 47 aum (om) shanti (silence, tranquility of Afghanistan, 21, 35, 219 mind, listening to inner voice, etc.), 180 ‘afw (forgiveness), 41 Ayoub, Mahmoud M., 11, 18–19 ahimsa (nonviolence), 180–2 Aztecs, 110 Ali, Abdullah Yusuf, 17 Alvarado, Pedro, 59 ba (hegemony), 126 American Indian veterans of the US war Babylonian Talmud, 83–4, 89, 93–4 against Vietnam, 212 baoli (violence), 123 American Israel Public Affairs Committee, 100 Bar Kosiba, Simon, 93, 105 American Jewish Committee, 101 Beatitudes, 51, 69 Anabaptists, 61 Bell, Daniel, 124 Analects, 112–14, 124 Bhagavad Gita (Gita), 14, 178, 181–2, 203 Anandavan, 190–91 bhakti (personal devotion), 180 anthropocentrism, 215–17 Bhave, Vinoba, 174, 194 Anti-Defamation League, 99 Bible, 2, 14–15, 84, 87, 90–1, 143, 149, 188, anti-semitism, 63 194, 217 Arab nationalism, 45 Bodhisattva, 143, 147–50, 153 Arab Spring, 21 Bonney, Richard, 15, 23 Arab-Israeli Wars, 96–7 Brahman (ultimate reality), 4, 154, 179, 198 Ariaratne, A. T., 158, 174 Brahmins, 173, 179, 184 Arjuna, 179, 181–3, 200 Buber, Martin, 89 Art of Living Foundation, 191 Buddha, 78, 80, 135–6, 143, 145, 147–8, Ashrams: communities practicing yoga 154–5, 157, 173–4, 185, 188, and serviceCOPYRIGHTED to others, 190 Buddhism MATERIAL forms: Asita, 135 Theravada, 142–4, 148, 152, 156 Athavale, Pandurang Shastri, 194 Mahayana, 76, 142, 136, 143–4, 147–8, atman (soul), 179, 198, 203–4 150, 152, 157, 160–3, 168 Peacemaking and the Challenge of Violence in World Religions, First Edition. -

Meeting in Exile

Meeting In Exile Gerald W. Schlabach Gerald W. Schlabach is associate professor of theology at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, and director of the university's Justice and Peace Studies Program. He is lead author and editor of Just Policing, Not War: An Alternative Response to World Violence (Liturgical Press, 2007) and co-editor of At Peace and Unafraid: Public Order, Security and the Wisdom of the Cross (Herald Press, 2007). From 2001 through 2007 he was executive director of Bridgefolk, a movement for grassroots dialogue and unity between Mennonites and Roman Catholics. For the three “historic peace church” colleges of Indiana to join together in the Plowshares Peace Studies Collaborative and its new Journal of Religion, Conflict, and Peace is altogether welcome and obviously fitting. The term “historic peace church” that links the Mennonite Church, the Religious Society of Friends, and the Church of the Brethren is, however, somewhat less obvious. Or rather, it has come to seem obvious mainly by historical accident, and then by force of habit. If the term had emerged in a context other than the United States in the years leading up to World War II, after all, other historic Christian communities might have been included, so, too, if the term ever undergoes revision in the twenty-first century. Just what constitutes a “peace church” in the first place? The question is deceptively simple. So let me begin by complicating it! A brief story may illuminate the complexity. In 1998 the first formal international ecumenical dialogue began between Mennonites and Roman Catholics. -

The International Peace Movement 1815-1914: an Outline

The international peace movement 1815-1914: an outline Script of an online lecture given by Guido Grünewald on 9 June 2020* I will try to give an outline of the emergence and development of an international peace movement during its first 100 years. Since English is not my mother tongue and I haven’t spoken it for a longer time I will follow a written guideline in order to finish the job in the short time I have. The first peace organisations emerged in America and in Britain. This was no coincidence; while on the European continent after the end of the Napoleonic Wars restoration took over there were evolving democracies in the anglo-Saxon countries and a kind of peace tradition as for example carried by the quakers who renounced any kind of war. For those early societies the question if a war could be defensive and therefore justified was from the beginning a thorny issue. The New York Peace Sciety founded by merchant David Low Dodge followed a fundamental pacifism rejecting all kind of wars while the Massachussets Peace Society (its founder was unitarian minister Noah Worcester) gathered both fundamental pacifists and those who accepted strictly defensive wars. With about 50 other groups both organisations merged to become the American Peace Society in 1828. The London Peace Society had an interesting top-tier approach: its leadership had to pursue a fundamental pacifist course while ordinary members were allowed to have different ideas about defensive wars. On the European continent some short-lived peace organisations emerged only later. The formation of those first societies occured under the influence of Quakers (one of the 3 historic peace churches which renounced violence) and of Christians who were convinced that war was murderous and incompatible with Christian values. -

A Preliminary Profile of the Nineteenth-Century US Peace Advocacy Press

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 361 717 CS 214 011 AUTHOR Roberts, Nancy L. TITLE A Preliminary Profile of theNineteenth-Century U.S. Peace Advocacy Press. PUB DATE Oct 93 NOTE 63p.; Paper presented at theAnnual Meeting of the American Journalism Historians Association(Salt Lake City, UT, October 6-9, 1993).Some of the material in the appendixes may not reproduce clearlydue to broken print or toner streaks. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Discourse Analysis; *Freedom of Speech;*Journalism History; Literary History; LiteratureReviews; *Peace; Periodicals; PersuasiveDiscourse; Press Opinion; Profiles; United StatesHistory IDENTIFIERS *Alternative Press; *NineteenthCentury; Rhetorical Strategies ABSTRACT Noting that throughout U.S. historymost viewpoints not expressed in the mainstreampress have found an outlet among alternative publications, thispaper presents a profile of the 19th century peace advocacypress. The paper also notes that most studies of peace history have beenproduced by scholars of diplomatic, military, and political history, who have viewed the field withinthe framework of their respective disciplines. Analyzing the field froma communication perspective, the firstpaper presents a review of the literature on peace history andthe history of the peace advocacy press. The paper then traces the 19thcentury peace advocacy movement and its presses; and after thatpresents an analysis of a sample of peace advocacy periodicals, examiningmethod, purpose and audience, overview of content, view ofreform and journalism,concern with other media, coverage of otherreform efforts, andsome journalistic strategies. The paper concludesthat the moral and ideological exclusion experienced 'bypeace advocates may have significantly shaped their communication. Twoappendixes provide: (1)a taxonomy of 19th century peace advocacy and its publications, and (2)selected examples of 19th centurypeace advocacy publications. -

Losurdo, Domenico. Non-Violence: a History Beyond the Myth Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015

The Philosophical Journal of Conflict and Violence Vol. I, Issue 2/2017 © The Authors, 2017 Available online at http://trivent-publishing.eu/ Losurdo, Domenico. Non-Violence: A History beyond the Myth Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015. vii + 246 pp. Domenico Losurdo, in his book Non-Violence: A History Beyond the Myth, aims to demonstrate the historical contradictions of non-violent action. This book embraces two centuries of the history of non-violence, reconstructing the great historical crises that this movement has faced from its inception. In his analysis, Losurdo does not limit himself to a history of the ideas, but instead investigates theories, political opinions, contradictions, moral dilemmas, and concrete behaviors in the context of central historical crises and transformations. Losurdo affirms that the popularity of non-violence movements is in part based on frustration with wars and revolutions that promised to achieve a state of perpetual peace by implementing their different methods. In other words, violence was used to guarantee the eradication of the scourge of violence once and for all. The First World War was greeted by mass enthusiasm to enlist in “the war to end all wars.” Similarly, the revolution in Russia was expected to overcome the brutality of capitalist exploitation and war. Therefore, we are familiar with the blood and tears that have dirtied projects to change the world through war or revolution, but what do we know of the dilemmas, “betrayals,” disappointments, and veritable tragedies that have befallen the movement inspired by the ideal of non-violence (5)? The author recognises that the first group committed to build a socio-political order characterized by non-violence was the Christian abolitionists in the United States in the nineteenth century. -

These Strange Criminals: an Anthology Of

‘THESE STRANGE CRIMINALS’: AN ANTHOLOGY OF PRISON MEMOIRS BY CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS FROM THE GREAT WAR TO THE COLD WAR In many modern wars, there have been those who have chosen not to fight. Be it for religious or moral reasons, some men and women have found no justification for breaking their conscientious objection to vio- lence. In many cases, this objection has lead to severe punishment at the hands of their own governments, usually lengthy prison terms. Peter Brock brings the voices of imprisoned conscientious objectors to the fore in ‘These Strange Criminals.’ This important and thought-provoking anthology consists of thirty prison memoirs by conscientious objectors to military service, drawn from the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and centring on their jail experiences during the First and Second World Wars and the Cold War. Voices from history – like those of Stephen Hobhouse, Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, Ian Hamilton, Alfred Hassler, and Donald Wetzel – come alive, detailing the impact of prison life and offering unique perspectives on wartime government policies of conscription and imprisonment. Sometimes intensely mov- ing, and often inspiring, these memoirs show that in some cases, indi- vidual conscientious objectors – many well-educated and politically aware – sought to reform the penal system from within either by publicizing its dysfunction or through further resistance to authority. The collection is an essential contribution to our understanding of criminology and the history of pacifism, and represents a valuable addition to prison literature. peter brock is a professor emeritus in the Department of History at the University of Toronto. -

A History of Peace Education in the United States of America

1 A History of Peace Education in the United States of America Aline M. Stomfay-Stitz, Ed.D. University of North Florida INTRODUCTION Peace education has been studied at various times by scholars, activists, and reformers in the United States as a way to bring about greater harmony among groups of people, primarily through schools and classrooms. However, the history of peace education in America is largely hidden, and the legitimacy of the field has always been questioned in terms of its goals for research and advocacy. While there have been many definitions of peace education, the field is generally considered multi-disciplinary and includes a focus on peace studies, social justice, economic well-being (meeting basic needs), political participation (citizenship), nonviolence, conflict resolution, disarmament, human rights and concern for the environment (Stomfay-Stitz, 1993). Peace educators at various times have engaged with additional areas of inquiry including feminism, global education, and cultural diversity. One important rationale for American peace education has existed for decades, namely the escalation of the nuclear arms race during the second half of the twentieth century. Through research and advocacy, peace education in the United States has depended on hope rather than despair. Americans involved in peace education have long advocated for the recognition of the worth of others who may be different, who may speak other languages, and yet share the fate of this fragile planet, Earth. Through the research and advocacy of groups such as the U.S. Institute of Peace, numerous academic departments in peace studies and peace education including the International Institute for Peace Education at Teachers College, Columbia University, private organizations, and community-based Peace Centers, all have come together to create a cohort of believers, working with a collective motivation of attaining peace in the world.