Fostering Global Security: Nonviolent Resistance and US Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TM Sep7 04 717.Qxd

Thewww.TheMennonite.orgMennoniteSeptember 7, 2004 communities pursuing Christ’sChrist’spurpose Page 8 ommunities Cpursuing hrist’s Cpurpose FIRST IN A SERIES 11 CPT turns 20 18 Help eliminate global debt 16 Tragic zeal 32 Picking presidents GRACE AND TRUTH God is bigger than our language about God Or suppose a woman has 10 valuable silver coins But Jesus also described God as a woman who and loses one. Won’t she light a lamp and look in lost a coin. Again I hear that caution against settling every corner of the house and sweep every nook and on only one image of God, even one recommended cranny until she finds it? And when she finds it, she by Jesus. God is bigger than any single image pre- will call in her friends and neighbors to rejoice with sented in the Scripture. her because she has found her lost coin. In the same Provider, Savior, Redeemer, King, Lord, Warrior, way, there is joy in the presence of God’s angels when Mother, Father, Eagle, Rock, Fire, Light, Wind, even one sinner repents.—Luke 15:8-10 (NLT) Spirit, Son. The Scripture is full of different images of God. As we hold them together we discern the use inclusive language when I preach. It’s not outline of One far beyond anything or anyone we hard to do. Start by substituting “humanity” for can imagine. Singly these images may be easier to I “mankind.” It gets easier from there. This is not hold, they may create a sharper picture. But it is in praiseworthy but an attempt to leave room in the the aggregate that we discern the complexity, the sermon for everyone to enter. -

Brock on Curran, 'Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement'

H-Peace Brock on Curran, 'Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement' Review published on Monday, March 1, 2004 Thomas F. Curran. Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement. New York: Fordham University Press, 2003. xv + 228 pp. $45.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8232-2210-0. Reviewed by Peter Brock (Professor Emeritus of History, University of Toronto)Published on H- Peace (March, 2004) Dilemmas of a Perfectionist Dilemmas of a Perfectionist Thomas Curran's monograph originated in a Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Notre Dame but it has been much revised since. The book's clearly written and well-constructed narrative revolves around the person of an obscure package woolen commission merchant from Philadelphia named Alfred Henry Love (1830-1913), a radical pacifist activist who was also a Quaker in all but formal membership. Love is the key figure in the book, binding Curran's chapters together into a cohesive whole. And Love's papers, and particularly his unpublished "Journal," which are located at the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, form the author's most important primary source: in fact, he uses no other manuscript collections, although, as the endnotes and bibliography show, he is well read in the published primary and secondary materials, including work on the general background of both the Civil War era and nineteenth-century pacifism. Curran has indeed rescued Love himself from near oblivion; there is little else on him apart from an unpublished Ph.D. dissertation by Robert W. Doherty (University of Pennsylvania, 1962). -

Iraq's WMD Capability

BRITISH AMERICAN SECURITY INFORMATION COUNCIL BASIC SPECIAL REPORT Unravelling the Known Unknowns: Why no Weapons of Mass Destruction have been found in Iraq By David Isenberg and Ian Davis BASIC Special Report 2004.1 January 2004 1 The British American Security Information Council The British American Security Information Council (BASIC) is an independent research organization that analyzes international security issues. BASIC works to promote awareness of security issues among the public, policy makers and the media in order to foster informed debate on both sides of the Atlantic. BASIC in the U.K. is a registered charity no. 1001081 BASIC in the U.S. is a non-profit organization constituted under Section 501(c)(3) of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service Code David Isenberg, Senior Analyst David Isenberg joined BASIC's Washington office in November 2002. He has a wide background in arms control and national security issues, and brings close to 20 years of experience in this field, including three years as a member of DynMeridian's Arms Control & Threat Reduction Division, and nine years as Senior Analyst at the Center for Defense Information. Ian Davis, Director Dr. Ian Davis is Executive Director of BASIC and has a rich background in government, academia, and the non-governmental organization (NGO) sector. He received both his Ph.D. and B.A. in Peace Studies from the University of Bradford. He was formerly Program Manager at Saferworld before being appointed as the new Executive Director of BASIC in October 2001. He has published widely on British defense and foreign policy, European security, the international arms trade, arms export controls, small arms and light weapons and defense diversification. -

Historic Peace Churches People

The Consistent Life Ethic the vulnerable to only some groups of Mennonite: From Article 22 of the and the Historic Peace Churches people. Some care for the children in the Mennonite Confession of Faith - womb, children recently born with Mennonites, the Church of the Brethren, and disabilities, and the vulnerable among the ill. “Led by the Spirit, and beginning in the the Religious Society of Friends, which Yet they are not as clear about the problems church, we witness to all people that cooperated together in the "New Call to of war or the death penalty or policies that violence is not the will of God. We witness Peacemaking" project, have centuries of could help solve the problems of poverty against all forms of violence, including war experience in the insights of pacifism. This that threaten the very groups they assert among nations, hostility among races and is the understanding that violence is not protection for. They weaken their case by classes, abuse of children and women, ethical, nor is the apathy or cowardice that their inconsistency. Others are very sensitive violence between men and women, abortion, supports violence by others. Furthermore, to the problems of war and the death penalty and capital punishment.” the appearance of violence as a quick fix to and poverty while using euphemisms to problems is deceptive. Through hardened Brethren: From Pastor Wesley Brubaker, avoid the realities of feticide and infanticide, http://www.brfwitness.org/?p=390 hearts, lost opportunities, and over- and allowing the "right to die" become the simplified thinking, violence generally leads "duty to die" in a society still infested with “We seem to realize instinctively that to more problems and often exacerbates far too many prejudices against the abortion is gruesome. -

War Prevention Works 50 Stories of People Resolving Conflict by Dylan Mathews War Prevention OXFORD • RESEARCH • Groupworks 50 Stories of People Resolving Conflict

OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP war prevention works 50 stories of people resolving conflict by Dylan Mathews war prevention works OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP 50 stories of people resolving conflict Oxford Research Group is a small independent team of Oxford Research Group was Written and researched by researchers and support staff concentrating on nuclear established in 1982. It is a public Dylan Mathews company limited by guarantee with weapons decision-making and the prevention of war. Produced by charitable status, governed by a We aim to assist in the building of a more secure world Scilla Elworthy Board of Directors and supported with Robin McAfee without nuclear weapons and to promote non-violent by a Council of Advisers. The and Simone Schaupp solutions to conflict. Group enjoys a strong reputation Design and illustrations by for objective and effective Paul V Vernon Our work involves: We bring policy-makers – senior research, and attracts the support • Researching how policy government officials, the military, of foundations, charities and The front and back cover features the painting ‘Lightness in Dark’ scientists, weapons designers and private individuals, many of decisions are made and who from a series of nine paintings by makes them. strategists – together with Quaker origin, in Britain, Gabrielle Rifkind • Promoting accountability independent experts Europe and the and transparency. to develop ways In this United States. It • Providing information on current past the new millennium, has no political OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP decisions so that public debate obstacles to human beings are faced with affiliations. can take place. nuclear challenges of planetary survival 51 Plantation Road, • Fostering dialogue between disarmament. -

Just the Police Function, Then a Response to “The Gospel Or a Glock?”

Just the Police Function, Then A Response to “The Gospel or a Glock?” Gerald W. Schlabach Introduction Consider this thought experiment: Adam and Eve have not yet sinned. In fact, they will not sin for a few decades and have begun their family. It is time for supper, but little Cain and his brother Abel are distracted. They bear no ill will, but their favorite pets, the lion and lamb, are particularly cute as they frolic together this afternoon. So Adam goes to find and hurry them home. With nary an unkind word and certainly no violence, he polices their behavior and orders their community life. For like every social arrangement, even this still-altogether-faithful community requires the police function too. A pacifist who does not recognize this point is likely to misconstrue everything I have written about “just policing.”1 Having lived a vocation for mediating between polarized Christian communities since my years in war- torn Central America, I expected a measure of misunderstanding when I proposed the agenda of just policing as a way to move ecumenical dialogue forward between pacifist and just war Christians, especially Mennonites and Catholics. Whoever seeks to engage the estranged in conversation simultaneously on multiple fronts will take such a risk.2 Deeply held identities are often at stake, and as much as the mediator may do to respect community boundaries, he or she can hardly help but threaten them simply by crossing back and forth. The risk of misunderstanding comes with the liminal territory, and nothing but a doggedly hopeful patience for continued conversation will minimize it. -

N Ieman Reports

NIEMAN REPORTS Nieman Reports One Francis Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 21 ST CENTURY MUCKRAKERS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION HARVARDAT UNIVERSITY 21st Century Muckrakers Who Are They? How Do They Do Their Work? Words & Reflections: Secrets, Sources and Silencing Watchdogs Journalism 2.0 End Note went to the Carnegie Endowment in New York but of the Oakland Tribune, and Maynard was throw- found times to return to Cambridge—like many, ing out questions fast and furiously about my civil I had “withdrawal symptoms” after my Harvard rights coverage. I realized my interview was lasting ‘to promote and elevate the year—and would meet with Tenney. She came to longer than most, and I wondered, “Is he trying to my wedding in Toronto in 1984, and we tried to knock me out of competition?” Then I happened to keep in touch regularly. Several of our class, Peggy glance over at Tenney and got the only smile from standards of journalism’ Simpson, Peggy Engel, Kat Harting, and Nancy the group—and a warm, welcoming one it was. I Day visited Tenney in her assisted living facility felt calmer. Finally, when the interview ended, I in Cambridge some years ago, during a Nieman am happy to say, Maynard leaped out of his chair reunion. She cared little about her own problems and hugged me. Agnes Wahl Nieman and was always interested in others. Curator Jim Tenney was a unique woman, and I thoroughly Thomson was the public and intellectual face of enjoyed her friendship. -

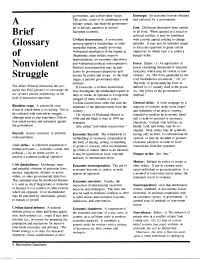

A Brief Glossary of Nonviolent Struggle

government, and subvert their troops. Embargo: An economic boycott initiated This policy, alone or in combination with and enforced by a government. A military means, has received governmen- tal or military attention in several Fast: Deliberate abstention from certain European countries. or all food. When applied in a social or Brief political conflict, it may be combined Civilian insurrection: A nonviolent with a moral appeal seeking to change Glossary uprising against a dictatorship, or other attitudes. It may also be intended simply unpopular regime, usually involving to force the opponent to grant certain widespread repudiation of the regime as objectives, in which case it is called a of illegitimate, mass strikes, massive hunger strike. demonstrations, an economic shut-down, and widespread political noncooperation. Force: Either: (1) An application of Nonviolent Political noncooperation may include power (including threatened or imposed action by government employees and sanctions, which may be violent or non- Struggle mutiny by police and troops. In the final violent). As, "the force generated by the stages, a parallel government often civil disobedience movement." Or: (2) emerges. The body or group applying force as The Albert Einstein Institution has pre- If successful, a civilian insurrection defined in (1), usually used in the plural. pared this brief glossary to encourage the may disintegrate the established regime in As, "the forces at the government's use of more precise terminology in the days or weeks, as opposed to a long-term disposal." field of nonviolent sanctions. struggle of many months or years. Civilian insurrections often end with the General strike: A work stoppage by a Bloodless coup: A successful coup departure of the deposed rulers from the majority of workers in the more impor- d'etat in which there is no killing. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

NON-VIOLENCE NEWS February 2016 Issue 2.5 ISSN: 2202-9648

NON-VIOLENCE NEWS February 2016 Issue 2.5 ISSN: 2202-9648 Nonviolence Centre Australia dedicates 30th January, Martyrs’ Day to all those Martyrs who were sacrificed for their just causes. I have nothing new to teach the world. Truth and Non-violence are as old as the hills. All I have done is to try experiments in both on as vast a scale as I could. -Mahatma Gandhi February 2016 | Non-Violence News | 1 Mahatma Gandhi’s 5 Teachings to bring about World Peace “If humanity is to progress, Gandhi is inescapable. He lived, with lies within our hearts — a force of love and thought, acted and inspired by the vision of humanity evolving tolerance for all. Throughout his life, Mahatma toward a world of peace and harmony.” - Dr. Martin Luther Gandhi fought against the power of force during King, Jr. the heyday of British rein over the world. He transformed the minds of millions, including my Have you ever dreamed about a joyful world with father, to fight against injustice with peaceful means peace and prosperity for all Mankind – a world in and non-violence. His message was as transparent which we respect and love each other despite the to his enemy as it was to his followers. He believed differences in our culture, religion and way of life? that, if we fight for the cause of humanity and greater justice, it should include even those who I often feel helpless when I see the world in turmoil, do not conform to our cause. History attests to a result of the differences between our ideals. -

2018 3 9 Catalog

LANCASTER MENNONITE HISTORICAL SOCIETY’S BENEFIT AUCTION OF RARE, OUT-OF-PRINT, AND USED BOOKS FRIDAY, MARCH 9, 2018, AT 6:30 P.M. TEL: (717) 393-9745; FAX: (717) 393-8751; EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http://www.lmhs.org/ The Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society will conduct an auction on March 9, 2018, at 2215 Millstream Road, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, one-half mile east of the intersection of Routes 30 and 462. The sale dates for the remainder of 2018 are as follows: May 11, July 13, September 14 and November 9. Please refer to the last page of the catalog for book auction procedures. Individual catalogs are available from the Society for $5.00 + $3.00 postage and handling. Persons who wish to be added to the mailing list for the rest of 2018 may do so by sending $15.00 with name and address to the Society. Higher rates apply for subscribers outside of the United States. All subscriptions expire at the end of the calendar year. The catalog is also available for free on our web site at www.lmhs.org/auction.html. 1. Bender, Harold S. Conrad Grebel, c. 1498-1526, the Founder of the Swiss Brethren, Sometimes Called Anabaptists. Studies in Anabaptist and Mennonite History, no. 6, vol. 1. Goshen, Ind.: Mennonite Historical Society, 1950. xvi, 326pp (b/w ill, bib, ind, copy of author, syp, gc). 2. Friedmann, Robert. Mennonite Piety Through the Centuries: Its Genius and Its Literature. Studies in Anabaptist and Mennonite History, no. 7. Goshen, Ind.: Mennonite Historical Society, 1949. xv, [i], 287pp (fp, b/w ill, bib, ind, presentation copy signed by author, syp, gc). -

HISTORY 174F Gandhi and the Making of Modern India UCLA, Spring 2016: Tue & Thurs, 11-12:15, Dodd 161

HISTORY 174F Gandhi and the Making of Modern India UCLA, Spring 2016: Tue & Thurs, 11-12:15, Dodd 161 Instructor: Vinay Lal Office: Bunche 5240; tel: 310.825.8276; e-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesdays, 1-3:30 PM, and by appointment History Department: Bunche 6265; tel: 310.825.4601 Course Website: https://moodle2.sscnet.ucla.edu/course/view/16S-HIST174F-1 Instructor’s Web Site [MANAS]: http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/southasia Instructor’s Personal Academic Site: http://www.vinaylal.com Instructor’s Blog: https://vinaylal.wordpress.com/ This course will examine the life and ideas of Mohandas Karamchand (‘Mahatma’) Gandhi (1869-1948), most renowned as the ‘prophet of nonviolence’ and the architect of the Indian independence movement, though in the concluding portion of the course we will also consider some of the various ways in which his presence is experienced in India today and the controversies surrounding his achievements and ‘legacy’. Gandhi was a great deal more than a nonviolent activist and political leader: he was a spiritual thinker, social reformer, critic of modernity and industrial civilization, interpreter of Indian civilization, a staunch supporter of Indian syncretism, a major figure in Indian journalism, and a forerunner, not only in India, of the many of the great social and ecological movements of our times. After the first three weeks, we will only partly follow the chronological framework within which the biographies of Gandhi have been constructed, and around which a great deal of the scholarship still revolves, and more so when we need to understand how Gandhi’s thoughts on a particular subject evolved over time.