Hitler: Speeches and Proclamations, Volume II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vice Admiral Luke M. Mccollum Chief of Navy Reserve Commander, Navy Reserve Force

2/16/2017 U.S. Navy Biographies VICE ADMIRAL LUKE M. MCCOLLUM Vice Admiral Luke M. McCollum Chief of Navy Reserve Commander, Navy Reserve Force Vice Adm. Luke McCollum is a native of Stephenville, Texas, and is the son of a WWII veteran. He is a 1983 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and is a designated surface warfare officer. McCollum holds a Master of Science in Computer Systems Management from the University of Maryland, University College and is also a graduate of Capstone, the Armed Forces Staff College Advanced Joint Professional Military Education curriculum and the Royal Australian Naval Staff College in Sydney. At sea, McCollum served on USS Blue Ridge (LCC 19), USS Kinkaid (DD 965) and USS Valley Forge (CG 50), with deployments to the Western Pacific, Indian Ocean, Arabian Gulf and operations off South America. Ashore, he served in the Pentagon as naval aide to the 23rd chief of naval operations (CNO). In 1993 McCollum accepted a commission in the Navy Reserve where he has since served in support of Navy and joint forces worldwide. He has commanded reserve units with U.S. Fleet Forces Command, Military Sealift Command and Naval Coastal Warfare. From 2008 to 2009, he commanded Maritime Expeditionary Squadron (MSRON) 1 and Combined Task Group 56.5 in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. He also served as the Navy Emergency Preparedness liaison officer (NEPLO) for the state of Arkansas. As a flag officer, McCollum has served as reserve deputy commander, Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet; vice commander, Naval Forces, Central Command, Manama, Bahrain; Reserve deputy director, Maritime Headquarters, U.S. -

D'antonio, Michael Senior Thesis.Pdf

Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Degree in History with Distinction Spring 2016 © 2016 Michael D’Antonio All Rights Reserved Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. James Brophy Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. David Shearer Committee member from the Department of History Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. Barbara Settles Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Michael Arnold, Ph.D. Director, University Honors Program ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This senior thesis would not have been possible without the assistance of Dr. James Brophy of the University of Delaware history department. His guidance in research, focused critique, and continued encouragement were instrumental in the project’s formation and completion. The University of Delaware Office of Undergraduate Research also deserves a special thanks, for its continued support of both this work and the work of countless other students. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................. -

Väsen I Chronopia Creatures of Chronopia Konstruktör: Johan

Väsen i Chronopia Creatures of Chronopia Konstruktör: Johan Sjöberg Översättning: Redigering: Chronopia: Bill King, Michael Stenmark, Nils Gulliksson, Henrik Strandberg Formgivning: Original: Marcus Thorell Omslag: Adrian Smith Grafisk Form: Illustrationer: Adrian Smith, Alvaro Tapia Koncept: Stefan Ljungqvist, Johan Sjöberg Kartor: Övriga Bidrag: Filip Alexanderson, Hanners Kristoferson, Fredrik Malmberg, Henrik Strandberg, Nils Gulliksson, Sami Sinerva, Jonas Mases, Patric Backlund, Cees Kwadijk Baksida: Paolo Parente Projektledning: Stefan Ljungqvist So you want to learn something about the chronopian people? Forsa the sabranska mysteries, get to know the secrets that made brundusierna so rich, understand marajiputternas brutal fanaticism and unconditional surrender to the black tobacco, nattländarnas desperate escape and ice barbarians worship of Snow Witch. Then I have the book for you my friend. Just look up Melkastors "The chronopian peoples", which delivers the wise man and adventurer all the wisdom you need. If he is still alive? No. When the book arrived, he was executed for blasphemy by the emperor. Read - and maybe you will understand why. Human ethnicities During my many long and intense years as a guest in the brutal, multifaceted and legendary chronopian reality, I had the dubious pleasure to encounter the most varied gallery of the known world has to offer, bump into high and low, exchange experiences with sabranska desert knights, brundusiska trade princes and blue skinned isbarbarer with frosty mustache. I have engaged in telepathy with charibiska hexbarons, given boozed Red Corsairs on the nut, fled howling marajiputtiska fanatics and young and inexperienced taken refuge in faltrakiernas false bosom and sold as a slave to the salt mines. -

Arms Procurement Decision Making Volume II: Chile, Greece, Malaysia

4. Malaysia Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam* I. Introduction Malaysia has become one of the major political players in the South-East Asian region with increasing economic weight. Even after the economic crisis of 1997–98, despite defence budgets having been slashed, the country is still deter- mined to continue to modernize and upgrade its armed forces. Malaysia grappled with the communist insurgency between 1948 and 1962. It is a democracy with a strong government, marked by ethnic imbalances and affirmative policies, strict controls on public debate and a nascent civil society. Arms procurement is dominated by the military. Public apathy and indifference towards defence matters have been a noticeable feature of the society. Public opinion has disregarded the fact that arms procurement decision making is an element of public policy making as a whole, not only restricted to decisions relating to military security. An examination of the country’s defence policy- making processes is overdue. This chapter inquires into the role, methods and processes of arms procure- ment decision making as an element of Malaysian security policy and the public policy-making process. It emphasizes the need to focus on questions of public accountability rather than transparency, as transparency is not a neutral value: in many countries it is perceived as making a country more vulnerable.1 It is up 1 Ball, D., ‘Arms and affluence: military acquisitions in the Asia–Pacific region’, eds M. Brown et al., East Asian Security (MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass., 1996), p. 106. * The author gratefully acknowledges the help of a number of people in putting this study together. -

The Development and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Isdap Electoral Breakthrough

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 The evelopmeD nt and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough. Thomas Wiles Arafe Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Arafe, Thomas Wiles Jr, "The eD velopment and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2909. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2909 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. « The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing pega(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Ledning I Försvarsmakten Svenska Militära Chefers Erfarenheter

Ledning i Försvarsmakten Svenska militära chefers erfarenheter MAGDALENA GRANÅSEN, LINDA SJÖDIN, HELENA GRANLUND FOI är en huvudsakligen uppdragsfinansierad myndighet under Försvarsdepartementet. Kärnverksamheten är forskning, metod- och teknikutveckling till nytta för försvar och säkerhet. Organisationen har cirka 1000 anställda varav ungefär 800 är forskare. Detta gör organisationen till Sveriges största forskningsinstitut. FOI ger kunderna tillgång till ledande expertis inom ett stort antal tillämpningsområden såsom säkerhetspolitiska studier och analyser inom försvar och säkerhet, bedömning av olika typer av hot, system för ledning och hantering av kriser, skydd mot och hantering av farliga ämnen, IT-säkerhet och nya sensorers möjligheter. FOI Totalförsvarets forskningsinstitut Tel: 08-55 50 30 00 www.foi.se Försvarsanalys Fax: 08-55 50 31 00 164 90 Stockholm FOI-R--3375--SE Underlagsrapport Försvarsanalys ISSN 1650-1942 December 2011 Magdalena Granåsen, Linda Sjödin, Helena Granlund Ledning i Försvarsmakten Svenska militära chefers erfarenheter Omslagsbild: Bildkollage av Henric Roosberg FOI-R--3375--SE Ledning i Försvarsmakten. Svenska militära chefers Titel erfarenheter. Title Command and Control in the Swedish Armed Forces. Experiences of Swedish military commanders. Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--3375--SE Rapporttyp/ Report Type Underlagsrapport/ Base data report Sidor/Pages 25 p Månad/Month December Utgivningsår/Year 2011 ISSN Kund/Customer Försvarsmakten Projektnr/Project no E11109 Godkänd av/Approved by Markus Derblom FOI, Totalförsvarets -

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government Historical Culture, Conflicting Memories and Identities in post-Soviet Estonia Meike Wulf Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of London London 2005 UMI Number: U213073 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U213073 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Ih c s e s . r. 3 5 o ^ . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract This study investigates the interplay of collective memories and national identity in Estonia, and uses life story interviews with members of the intellectual elite as the primary source. I view collective memory not as a monolithic homogenous unit, but as subdivided into various group memories that can be conflicting. The conflict line between ‘Estonian victims’ and ‘Russian perpetrators* figures prominently in the historical culture of post-Soviet Estonia. However, by setting an ethnic Estonian memory against a ‘Soviet Russian’ memory, the official historical narrative fails to account for the complexity of the various counter-histories and newly emerging identities activated in times of socio-political ‘transition’. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia -

"Weapon of Starvation": the Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2015 A "Weapon of Starvation": The Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919 Alyssa Cundy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Cundy, Alyssa, "A "Weapon of Starvation": The Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919" (2015). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1763. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1763 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A “WEAPON OF STARVATION”: THE POLITICS, PROPAGANDA, AND MORALITY OF BRITAIN’S HUNGER BLOCKADE OF GERMANY, 1914-1919 By Alyssa Nicole Cundy Bachelor of Arts (Honours), University of Western Ontario, 2007 Master of Arts, University of Western Ontario, 2008 DISSERTATION Submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in History Wilfrid Laurier University 2015 Alyssa N. Cundy © 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the British naval blockade imposed on Imperial Germany between the outbreak of war in August 1914 and the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles in July 1919. The blockade has received modest attention in the historiography of the First World War, despite the assertion in the British official history that extreme privation and hunger resulted in more than 750,000 German civilian deaths. -

University of Bradford Ethesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. THE WHITE INTERNATIONAL: ANATOMY OF A TRANSNATIONAL RADICAL REVISIONIST PLOT IN CENTRAL EUROPE AFTER WORLD WAR I Nicholas Alforde Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2013 Principal Supervisor: Gábor Bátonyi, DPhil Abstract Nicholas Alforde The White International: Anatomy of a Transnational Radical Revisionist Plot in Central Europe after World War I Keywords: Bauer, Gömbös, Horthy, Ludendorff, Orgesch, paramilitary, Prónay, revision, Versailles, von Kahr The denial of defeat, the harsh Versailles Treaty and unsuccessful attempts by paramilitary units to recover losses in the Baltic produced in post-war Germany an anti- Bolshevik, anti-Entente, radical right-wing cabal of officers with General Ludendorff and Colonel Bauer at its core. Mistakenly citing a lack of breadth as one of the reason for the failure of their amateurishly executed Hohenzollern restoration and Kapp Putsch schemes, Bauer and co-conspirator Ignatius Trebitsch-Lincoln devised the highly ambitious White International plot. It sought to form a transnational league of Bavaria, Austria and Hungary to force the annulment of the Paris Treaties by the coordinated use of paramilitary units from the war vanquished nations. It set as its goals the destruction of Bolshevism in all its guises throughout Europe, the restoration of the monarchy in Russia, the systematic elimination of all Entente-sponsored Successor States and the declaration of war on the Entente. -

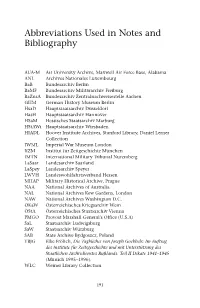

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74.