Draft Species Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unsustainable Food Systems Threaten Wild Crop and Dolphin Species

INTERNATIONAL PRESS RELEASE Embargoed until: 07:00 GMT (16:00 JST) 5 December 2017 Elaine Paterson, IUCN Media Relations, t+44 1223 331128, email [email protected] Goska Bonnaveira, IUCN Media Relations, m +41 792760185, email [email protected] [In Japan] Cheryl-Samantha MacSharry, IUCN Media Relations, t+44 1223 331128, email [email protected] Download photographs here Download summary statistics here Unsustainable food systems threaten wild crop and dolphin species Tokyo, Japan, 5 December 2017 (IUCN) – Species of wild rice, wheat and yam are threatened by overly intensive agricultural production and urban expansion, whilst poor fishing practices have caused steep declines in the Irrawaddy Dolphin and Finless Porpoise, according to the latest update of The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™. Today’s Red List update also reveals that a drying climate is pushing the Ringtail Possum to the brink of extinction. Three reptile species found only on an Australian island – the Christmas Island Whiptail-skink, the Blue- tailed Skink (Cryptoblepharus egeriae) and the Lister’s Gecko – have gone extinct, according to the update. But in New Zealand, conservation efforts have improved the situation for two species of Kiwi. “Healthy, species-rich ecosystems are fundamental to our ability to feed the world’s growing population and achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goal 2 – to end hunger by 2030,” says IUCN Director General Inger Andersen. “Wild crop species, for example, maintain genetic diversity of agricultural crops -

Proposal to Construct and Operate a Satellite Launching Facility on Christmas Island

Environment Assessment Report PROPOSAL TO CONSTRUCT AND OPERATE A SATELLITE LAUNCHING FACILITY ON CHRISTMAS ISLAND Environment Assessment Branch 2 May 2000 Christmas Island Satellite Launch Facility Proposal Environment Assessment Report - Environment Assessment Branch – May 2000 3 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................6 1.1 GENERAL ...........................................................................................................6 1.2 ENVIRONMENT ASSESSMENT............................................................................7 1.3 THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS ...............................................................................7 1.4 MAJOR ISSUES RAISED DURING THE PUBLIC COMMENT PERIOD ON THE DRAFT EIS .................................................................................................................9 1.4.1 Socio-economic......................................................................................10 1.4.2 Biodiversity............................................................................................10 1.4.3 Roads and infrastructure .....................................................................11 1.4.4 Other.......................................................................................................12 2 NEED FOR THE PROJECT AND KEY ALTERNATIVES ......................14 2.1 NEED FOR THE PROJECT ..................................................................................14 2.2 KEY -

ONEP V09.Pdf

Compiled by Jarujin Nabhitabhata Tanya Chan-ard Yodchaiy Chuaynkern OEPP BIODIVERSITY SERIES volume nine OFFICE OF ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY AND PLANNING MINISTRY OF SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT 60/1 SOI PIBULWATTANA VII, RAMA VI RD., BANGKOK 10400 THAILAND TEL. (662) 2797180, 2714232, 2797186-9 FAX. (662) 2713226 Office of Environmental Policy and Planning 2000 NOT FOR SALE NOT FOR SALE NOT FOR SALE Compiled by Jarujin Nabhitabhata Tanya Chan-ard Yodchaiy Chuaynkern Office of Environmental Policy and Planning 2000 First published : September 2000 by Office of Environmental Policy and Planning (OEPP), Thailand. ISBN : 974–87704–3–5 This publication is financially supported by OEPP and may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non–profit purposes without special permission from OEPP, providing that acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purposes. Citation : Nabhitabhata J., Chan ard T., Chuaynkern Y. 2000. Checklist of Amphibians and Reptiles in Thailand. Office of Environmental Policy and Planning, Bangkok, Thailand. Authors : Jarujin Nabhitabhata Tanya Chan–ard Yodchaiy Chuaynkern National Science Museum Available from : Biological Resources Section Natural Resources and Environmental Management Division Office of Environmental Policy and Planning Ministry of Science Technology and Environment 60/1 Rama VI Rd. Bangkok 10400 THAILAND Tel. (662) 271–3251, 279–7180, 271–4232–8 279–7186–9 ext 226, 227 Facsimile (662) 279–8088, 271–3251 Designed & Printed :Integrated Promotion Technology Co., Ltd. Tel. (662) 585–2076, 586–0837, 913–7761–2 Facsimile (662) 913–7763 2 1. -

The Contribution of Policy, Law, Management, Research, and Advocacy Failings to the Recent Extinctions of Three Australian Vertebrate Species

This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Woinarski, J. C. Z., Garnett, S. T., Legge, S. M., & Lindenmayer, D. B. (2017). The contribution of policy, law, management, research, and advocacy failings to the recent extinctions of three Australian vertebrate species. Conservation Biology, 31(1), 13-23; which has been published in final form at http://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12852 This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. The contribution of policy, law, management, research, and advocacy failings to the recent extinctions of three Australian vertebrate species John C.Z. Woinarski,*,a Stephen T. Garnett,* Sarah M. Legge,* † David B. Lindenmayer ‡ * Threatened Species Recovery Hub of the National Environment Science Programme, Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory 0909, Australia, † Threatened Species Recovery Hub of the National Environment Science Programme, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland 4072, Australia ‡ Threatened Species Recovery Hub of the National Environment Science Programme, Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia aemail [email protected] Keywords: Bramble Cay melomys, Christmas Island forest skink, Christmas Island pipistrelle, conservation policy, inquest, legislation, threatened species Running head: Extinction contributing factors Abstract Extinctions typically have ecological drivers, such as habitat loss. However, extinction events are also influenced by policy and management settings that may be antithetical to biodiversity conservation, inadequate to prevent extinction, insufficiently resourced, or poorly implemented. Three endemic Australian vertebrate species – the Christmas Island pipistrelle (Pipistrellus murrayi), Bramble Cay melomys (Melomys rubicola), and Christmas Island forest skink (Emoia nativitatis) – became extinct from 2009 to 2014. -

The Herpetofauna of Timor-Leste: a First Report 19 Doi: 10.3897/Zookeys.109.1439 Research Article Launched to Accelerate Biodiversity Research

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 109: 19–86 (2011) The herpetofauna of Timor-Leste: a first report 19 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.109.1439 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.zookeys.org Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The herpetofauna of Timor-Leste: a first report Hinrich Kaiser1, Venancio Lopes Carvalho2, Jester Ceballos1, Paul Freed3, Scott Heacox1, Barbara Lester3, Stephen J. Richards4, Colin R. Trainor5, Caitlin Sanchez1, Mark O’Shea6 1 Department of Biology, Victor Valley College, 18422 Bear Valley Road, Victorville, California 92395, USA; and The Foundation for Post-Conflict Development, 245 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, New York 10167, USA 2 Universidade National Timor-Lorosa’e, Faculdade de Ciencias da Educaçao, Departamentu da Biologia, Avenida Cidade de Lisboa, Liceu Dr. Francisco Machado, Dili, Timor-Leste 3 14149 S. Butte Creek Road, Scotts Mills, Oregon 97375, USA 4 Conservation International, PO Box 1024, Atherton, Queensland 4883, Australia; and Herpetology Department, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia 5 School of Environmental and Life Sciences, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory 0909, Australia 6 West Midland Safari Park, Bewdley, Worcestershire DY12 1LF, United Kingdom; and Australian Venom Research Unit, Department of Pharmacology, University of Melbourne, Vic- toria 3010, Australia Corresponding author: Hinrich Kaiser ([email protected]) Academic editor: Franco Andreone | Received 4 November 2010 | Accepted 8 April 2011 | Published 20 June 2011 Citation: Kaiser H, Carvalho VL, Ceballos J, Freed P, Heacox S, Lester B, Richards SJ, Trainor CR, Sanchez C, O’Shea M (2011) The herpetofauna of Timor-Leste: a first report. ZooKeys 109: 19–86. -

A New Record of the Christmas Island Blind Snake, Ramphotyphlops Exocoeti (Reptilia: Squamata: Typhlopidae)

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 27 156–160 (2012) A new record of the Christmas Island Blind Snake, Ramphotyphlops exocoeti (Reptilia: Squamata: Typhlopidae). Dion J. Maple1, Rachel Barr, Michael J. Smith 1 Christmas Island National Park, Christmas Island, Western Australia, Indian Ocean, 6798, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT – The endemic Christmas Island Blind Snake Ramphotyphlops exocoeti is a species rarely collected since initial faunal collections were conducted on Christmas Island in 1887. Twenty-three years after the last record in 1986, an individual was collected on 31 July 2009. Here we catalogue historical collection records of this animal. We also describe the habitat and conditions in which the recent collection occurred and provide a brief morphological description of the animal including a diagnostic feature that may assist in future identifi cations. This account provides the fi rst accurate spatial record and detailed description of habitat utilised by this species. KEYWORDS: Indian Ocean, Yellow Crazy Ant, recovery plan INTRODUCTION ‘fairly common’ and could be found under the trunks Christmas Island is located in the Indian Ocean of fallen trees. In 1975 a specimen collected from (10°25'S, 105°40'E), approximately 360 km south of the Stewart Hill, located in the central west of the island western head of Java, Indonesia (Geoscience Australia in a mine lease known as Field 22, was deposited in 2011). This geographically remote, rugged and thickly the Australian Museum (Cogger and Sadlier 1981). A vegetated island is the exposed summit of a large specimen was caught by N. Dunlop in 1984 while pit mountain. -

Range Extensions of Lycodon Capucinus BOIE, 1827 in Eastern

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Herpetozoa Jahr/Year: 2004 Band/Volume: 17_3_4 Autor(en)/Author(s): Kuch Ulrich, McGuire Jimmy A. Artikel/Article: Range Extensions of Lycodon capucinus BOIE, 1827 in eastern Indonesia 191-193 ©Österreichische Gesellschaft für Herpetologie e.V., Wien, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at SHORT NOTE HERPETOZOA 17 (3/4) Wien, 30. Dezember 2004 SHORT NOTE 191 Wiebeisheim (Aula). CRNOBRNJA-ISAILOVIC, J. & China, the Philippines, and Indonesia (DE ALEKSIC, I. (1999): First record of Coluber najadum Roou 1917; DE HAAS 1950; BOSCH 1985; EICHWALD (1831) in Serbia.-Arch. Biol. Sci., Belgrade; 51 (3): 47P-48P. DIMOVSKI, A. (1963): Herpetofauna ISKANDAR & COLIJN 2001). A recent colo- na skopska kotlina. I - zoogeografski i ekoloski pre- nization of Christmas Island, about 320 km gled.- Godisen zbornik Prirodno-matematickog fakul- south of Java, was reported by L. A. SMITH teta, Univerziteta u Skoplju, Skoplje; knjiga 14, (1988). In eastern Indonesia, L. capucinus Biologija2: 189-221. DIMOVSKI, A. (1966): Herpeto- fauna na skopska kotlina. II - faunisticki del.- Godisen has been known from central, southwestern, zbornik Prirodno-matematickog fakulteta, Univerziteta and southeastern Sulawesi (DE ROOU 1917; u Skoplju, Skoplje; knjiga 16, Biologija 4: 179-188. ISKANDAR & TJAN 1996) and from the DZUKIC, G (1972): Herpetoloska zbirka Prirodnjackog Lesser Sunda Islands of Sumbawa, Sumba, muzeja u Beogradu. (Herpetological collection of the Belgrade museum of natural history).- Glasnik Savu, Roti, Timor, Flores, Lomblem, Alor, Prirodnjackog muzeja, Beograd; (Ser. B) 27: 165-180. Lembata, and Wetar (DE ROOU 1917; How et DZUKIC, G (1995): Diverzitet vodozemaca (Amphibia) al. -

Survey of Reptiles and Amphibians at Bimblebox Nature Reserve - Queensland

Summary of an Observational Survey of Reptiles and Amphibians at Bimblebox Nature Reserve - Queensland Graham Armstrong – May, 2016 Objective - to provide an updated and more complete list of the herpetofauna recorded from Bimblebox Nature Refuge. Approach - 1. Review available data and records pertaining to the herpetofauna at Bimblebox Nature Refuge. 2. Visit Bimblebox Nature Refuge during Spring, Summer and Autumn seasons to make observational and photographic records of the herpetofauna observed. Methodology - In order to maximise the number of species recorded, 3 successive 2.5 day visits were made to BNR, one in September 2015, Jan 2016 and the end of April 2016. This approach potentially broadens the range of weather conditions experienced and hence variety of reptiles and amphibians encountered when compared to a single field visit. Survey methodology involved walking and driving around the nature refuge during the day and after dark (with the aid of a head torch to detect eye-shine). Active reptiles including those that ran for or from cover while passing by were recorded. Frequently, in situ photographic evidence of individuals was obtained and the photographs are available for the purpose of corroborating identification. To avoid any double counting of individual animals the Refuge was traversed progressively and the locations of animals were recorded using a GPS. During any one visit no area was traversed twice and when driving along tracks, reptiles were only recorded the first time a track was traversed unless a new species was detected at a later time. Available Records The most detailed list of reptiles and amphibians recorded as occurring on Bimblebox Nature Reserve comes from the standardised trapping program of Eric Vanderduys of CSIRO in Townsville. -

Christmas Island Getaway

Christmas Island Getaway www.ditravel.com.au 1300 813 391 Christmas Island Fly-Drive-Stay Duration: 8 days Departs: daily Stay: 7 nights apartment or lodge Travel style: Independent self-drive Booking code: CHRFDS8AZ Call DI Travel on 1300 813 391 Email [email protected] 8 Days Christmas Island Fly-Drive-Stay Getaway About the holiday Christmas Island is an Australian territory in the Indian Ocean, lying south of Java, Indonesia, and 2600 kilometres north west of Perth, Western Australia. What this small, rocky island lacks in size, it more than makes up for with its extraordinary wildlife and spectacular natural wonders! Known as the ‘Galapagos of the Indian Ocean’, Christmas Island is a haven for animals and sea creatures, with close to two-thirds of the island being a protected national park. The island is famous for its red crabs, sea birds, whale sharks and incredible coral reefs. The island’s close proximity to Asia also means there’s a wonderful blend of cultural influences. So there really are few places on our planet like this remote Australian island! Why you’ll love this trip… Indulge in an Australian island escape that’s unlike any other! Dive some of the world’s longest drop-offs & bathe beneath a rainforest waterfall Time it right to witness the amazing annual crab migration at the start of the wet season! Travel Dates Departs regularly* 2021 – 20 April to 15 June, 20 July to 15 September, 10 October to 10 December 2022 – 25 January to 31 March, 20 April to 15 June, 20 July to 15 September, 10 October to 10 December *Departures are subject to confirmation at time of booking. -

Biodiversity Report 2018 -2019

Shivaji University Campus Biodiversity Report 2018 -2019 Prepared by DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE, SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR ©Registrar, Shivaji University, Kolhapur (Maharashtra) All rights reserved. No part of this work be reproduced in any form by mimeograph or any other means without permission in writing from Shivaji University, Kolhapur (Maharashtra). ISBN: 978-93-85190-14-8 Published by: Prof. (Dr.) Vilas D. Nandavadekar Registrar, Shivaji University, Kolhapur. Phone: (0) 0231-2609063 (R) 0231-2609059 (M) +91-9421918134 Email: [email protected] Prof. (Dr.) R. K. Kamat Photo credits: Co-ordinator, Prof. (Dr.) P. D. Raut, Amol Chougule, Internal Quality Assurance Cell, Chetan Bhosale, Amit Mane. Shivaji University, Printed by: Kolhapur- 416 004. Shivaji University Press, (Maharashtra), India. Kolhapur-416 004. Phone: (O) 0231-2609087 Email: [email protected] Dedicated to Late Dr. (Ms.) Nilisha P. Desai Chief Editor Prof. (Dr.) Prakash D. Raut Editorial Team Dr. (Mrs.)Aasawari S. Jadhav Dr. Pallavi R. Bhosale Ms. Nirmala B. Pokharnikar Ms. Aarti A. Parit Ms. Priya R. Vasagadekar Ms. Sonal G. Chonde Ms. Sanjivani T. Chougale Mr. Amol A. Chougule Mr. Chetan S. Bhosale Field Team Ms. Nirmala Pokharnikar Ms. Aarti A. Parit Ms. Priya Vasagadekar Mr. Amol A. Chougule Ms. Sanjivani T. Chougale Mr. Amit R. Mane Mr. Chetan S. Bhosale Mr. Ajay V. Gaud Mr. Harshad V. Suryawanshi Prepared by: Department of Environmental Science, Shivaji University, Kolhapur. ISBN: 978-93-85190-14-8 EDITORIAL .... It is a proud moment for me to put forward the ‘Biodiversity Report 2018 - 2019’ of Shivaji University, Kolhapur. The richness of any area is measured by its species diversity. -

Introduction 3

1 ,QWURGXFWLRQ The inquiry process 1.1 On 8 November 2000 the Senate referred matters relating to the tender process for the sale of the Christmas Island Casino and Resort to the Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories, for inquiry and report by 5 April 2001. The reporting date was subsequently extended to 27 September 2001. The full terms of reference are set out at the beginning of this report. 1.2 The inquiry was advertised in the Territories’ Tattler on 1 December 2000 and nationally in The Australian on 6 December 2000. The Committee also wrote to relevant Commonwealth Departments and to a number of organisations, inviting submissions. 1.3 The Committee received fifteen submissions, which are listed at Appendix A, and eleven exhibits, listed at Appendix B. Submissions are available from the Committee’s web site at: www.aph.gov.au/house/committee/ncet 1.4 The Committee held public hearings in Canberra in February and June 2001, and in Perth and Christmas Island in April 2001. Details are listed at Appendix C. Structure of the report 1.5 This report is divided into six chapters. Chapter One provides a background to the inquiry and details on the social, political and economic framework of the Island; 2 RISKY BUSINESS Chapter Two details the history and operation of the Christmas Island Casino and Resort, from its opening in 1993 to its closure in 1998; Chapter Three details the tender and sale process of the casino and resort; Chapter Four examines the conduct of the tender process; Chapter Five examines the outcome of the sale of the casino and resort; and Chapter Six details a number of broader community concerns which formed the context of the inquiry. -

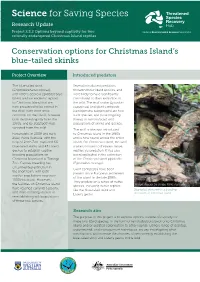

Science for Saving Species Research Update Project 2.3.2 Options Beyond Captivity for Two Critically Endangered Christmas Island Reptiles

Science for Saving Species Research Update Project 2.3.2 Options beyond captivity for two critically endangered Christmas Island reptiles Conservation options for Christmas Island’s blue-tailed skinks Project Overview Introduced predators The blue-tailed skink Several introduced predators (Cryptoblepharus egeriae) threaten these lizard species, and and Lister’s gecko (Lepidodactylus were likely to have significantly listeri) are two endemic reptiles contributed to their extinction in to Christmas Island that are the wild. The wolf snake (Lycodon now presumed to be extinct in capucinus) and giant centipede the Wild. Both were once (Scolopendra subspinipes) are two common on the Island, however such species, and pose ongoing both declined rapidly from the threats to reintroduced wild 1980s, and by 2012 both had populations of skinks and geckos. vanished from the wild. The wolf snake was introduced Fortunately, in 2009 and early to Christmas Island in the 1980s 2010, Parks Australia, with the and is now found across the entire help of Perth Zoo, captured 66 island. On Christmas Island, the wolf blue-tailed skinks and 43 Lister’s snake is known to threaten native geckos to establish captive reptiles via predation. It has also breeding populations on been implicated in the extinction Christmas Island and at Taronga of the Christmas Island pipistrelle Zoo. Captive breeding has (Pipistrellus murrayi). circumvented extinction in Giant centipedes have been the short term, with both present since European settlement captive populations now over of the island in the late 1880s. 1000individuals. However, They predate on a range of native the facilities on Christmas Island species, including native reptiles Image: Renata De Jonge, Parks Australia have reached carrying capacity, like the blue-tailed skink and Blue-tailed skinks within a breeding and there is strong interest in Lister’s gecko.