Introduction 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposal to Construct and Operate a Satellite Launching Facility on Christmas Island

Environment Assessment Report PROPOSAL TO CONSTRUCT AND OPERATE A SATELLITE LAUNCHING FACILITY ON CHRISTMAS ISLAND Environment Assessment Branch 2 May 2000 Christmas Island Satellite Launch Facility Proposal Environment Assessment Report - Environment Assessment Branch – May 2000 3 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................6 1.1 GENERAL ...........................................................................................................6 1.2 ENVIRONMENT ASSESSMENT............................................................................7 1.3 THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS ...............................................................................7 1.4 MAJOR ISSUES RAISED DURING THE PUBLIC COMMENT PERIOD ON THE DRAFT EIS .................................................................................................................9 1.4.1 Socio-economic......................................................................................10 1.4.2 Biodiversity............................................................................................10 1.4.3 Roads and infrastructure .....................................................................11 1.4.4 Other.......................................................................................................12 2 NEED FOR THE PROJECT AND KEY ALTERNATIVES ......................14 2.1 NEED FOR THE PROJECT ..................................................................................14 2.2 KEY -

O C E a N O C E a N C T I C P a C I F I C O C E a N a T L a N T I C O C E a N P a C I F I C N O R T H a T L a N T I C a T L

Nagurskoye Thule (Qanaq) Longyearbyen AR CTIC OCE AN Thule Air Base LAPTEV GR EENLA ND SEA EAST Resolute KARA BAFFIN BAY Dikson SIBERIAN BARENTS SEA SEA SEA Barrow SEA BEAUFORT Tiksi Prudhoe Bay Vardo Vadso Tromso Kirbey Mys Shmidta Tuktoyaktuk Narvik Murmansk Norilsk Ivalo Verkhoyansk Bodo Vorkuta Srednekolymsk Kiruna NORWEGIAN Urengoy Salekhard SEA Alaska Oulu ICELA Anadyr Fairbanks ND Arkhangelsk Pechora Cape Dorset Godthab Tura Kitchan Umea Severodvinsk Reykjavik Trondheim SW EDEN Vaasa Kuopio Yellowknife Alesund Lieksa FINLAND Plesetsk Torshavn R U S S Yakutsk BERING Anchorage Surgut I A NORWAY Podkamennaya Tungusk Whitehorse HUDSON Nurssarssuaq Bergen Turku Khanty-Mansiysk Apuka Helsinki Olekminsk Oslo Leningrad Magadan Yurya Churchill Tallin Stockholm Okhotsk SEA Juneau Kirkwall ESTONIA Perm Labrador Sea Goteborg Yedrovo Kostroma Kirov Verkhnaya Salda Aldan BAY UNITED KINGDOM Aluksne Yaroslavl Nizhniy Tagil Aberdeen Alborg Riga Ivanovo SEA Kalinin Izhevsk Sverdlovsk Itatka Yoshkar Ola Tyumen NORTH LATVIA Teykovo Gladkaya Edinburgh DENMARK Shadrinsk Tomsk Copenhagen Moscow Gorky Kazan OF BALTIC SEA Cheboksary Krasnoyarsk Bratsk Glasgow LITHUANIA Uzhur SEA Esbjerg Malmo Kaunas Smolensk Kaliningrad Kurgan Novosibirsk Kemerovo Belfast Vilnius Chelyabinsk OKHOTSK Kolobrzeg RUSSIA Ulyanovsk Omsk Douglas Tula Ufa C AN Leeds Minsk Kozelsk Ryazan AD A Gdansk Novokuznetsk Manchester Hamburg Tolyatti Magnitogorsk Magdagachi Dublin Groningen Penza Barnaul Shefeld Bremen POLAND Edmonton Liverpool BELARU S Goose Bay NORTH Norwich Assen Berlin -

Entités Géopolitiques Souveraines Ou Dépendantes, Triées Par

Code Code N O M F R A N Ç A I S N O M L O C A L ISO_2 ISO_3 éventuellement romanisé Le même code entre de l’entité souveraine de capitale de capitale LANGUE et code iso REMARQUES INDICATIVES parenthèses s’applique à plusieurs entités de l’entité dépendante de chef-lieu de chef-lieu Souveraineté AF AFG Afghanistan (l’) Kaboul Kābul pachto ps Kābol dari (persan) - ZA ZAF Afrique du Sud (l’) Pretoria Pretoria Kaapstad afrikaans af Y compris l’île Marion, l’île du Prince- Le Cap Pretoria Cape Town anglais en Édouard. Pretoria : capitale administrative et le siège du gouvernement. Le Cap : capitale législative Bloemfontein : capitale judiciaire AL ALB Albanie (l’) Tirana Tirana, Tiranë albanais sq DZ DZA Algérie (l’) Alger El Djezâir (Al Jazā’ir) arabe ar DE DEU Allemagne (l’) Berlin Berlin allemand de AD AND Andorre (l’) Andorre-la-Vieille Andorra la Vella catalan ca AO AGO Angola (l’) Luanda Luanda portugais pt Y compris Cabinda. (AQ) (ATA) Antarctique (l’) - - Continent à statut particulier. Suite au traité sur l'Antarctique signé en 1959 par douze États et suivi en 1991 par le protocole de Madrid. AG ATG Antigua-et-Barbuda Saint John’s Saint John’s anglais en Y compris l’île Redonda. SA SAU Arabie saoudite (l’) Riyad Ar i ā arabe ar AR ARG Argentine (l’) Buenos Aires Buenos Aires espagnol es AM ARM Arménie (l’) Erevan Yerevan arménien hy AU AUS Australie (l’) Canberra Canberra anglais en Y compris l’île Lord Howe, l’île Macquarie ; ainsi que les îles Ashmore-et-Cartier, et les îles de la mer de Corail, qui sont des territoires extérieurs australiens. -

ISO Country Codes

COUNTRY SHORT NAME DESCRIPTION CODE AD Andorra Principality of Andorra AE United Arab Emirates United Arab Emirates AF Afghanistan The Transitional Islamic State of Afghanistan AG Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda (includes Redonda Island) AI Anguilla Anguilla AL Albania Republic of Albania AM Armenia Republic of Armenia Netherlands Antilles (includes Bonaire, Curacao, AN Netherlands Antilles Saba, St. Eustatius, and Southern St. Martin) AO Angola Republic of Angola (includes Cabinda) AQ Antarctica Territory south of 60 degrees south latitude AR Argentina Argentine Republic America Samoa (principal island Tutuila and AS American Samoa includes Swain's Island) AT Austria Republic of Austria Australia (includes Lord Howe Island, Macquarie Islands, Ashmore Islands and Cartier Island, and Coral Sea Islands are Australian external AU Australia territories) AW Aruba Aruba AX Aland Islands Aland Islands AZ Azerbaijan Republic of Azerbaijan BA Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina BB Barbados Barbados BD Bangladesh People's Republic of Bangladesh BE Belgium Kingdom of Belgium BF Burkina Faso Burkina Faso BG Bulgaria Republic of Bulgaria BH Bahrain Kingdom of Bahrain BI Burundi Republic of Burundi BJ Benin Republic of Benin BL Saint Barthelemy Saint Barthelemy BM Bermuda Bermuda BN Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darussalam BO Bolivia Republic of Bolivia Federative Republic of Brazil (includes Fernando de Noronha Island, Martim Vaz Islands, and BR Brazil Trindade Island) BS Bahamas Commonwealth of the Bahamas BT Bhutan Kingdom of Bhutan -

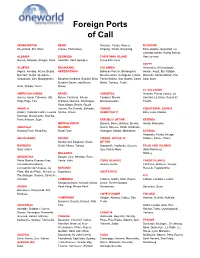

PORTS of CALL WORLDWIDE.Xlsx

Foreign Ports of Call AFGHANISTAN BENIN Shantou, Tianjin, Xiamen, ECUADOR Kheyrabad, Shir Khan Cotnou, Porto-Novo Xingang, Yantai, Zhanjiang Esmeraoldas, Guayaquil, La Libertad, Manta, Puerto Bolivar, ALBANIA BERMUDA CHRISTMAS ISLAND San Lorenzo Durres, Sarande, Shegjin, Vlore Hamilton, Saint George’s Flying Fish Cove EGYPT ALGERIA BOSNIAAND COLOMBIA Alexandria, Al Ghardaqah, Algiers, Annaba, Arzew, Bejaia, HERZEGOVINA Bahia de Portete, Barranquilla, Aswan, Asyut, Bur Safajah, Beni Saf, Dellys, Djendjene, Buenaventura, Cartagena, Leticia, Damietta, Marsa Matruh, Port Ghazaouet, Jijel, Mostaganem, Bosanka Gradiska, Bosakni Brod, Puerto Bolivar, San Andres, Santa Said, Suez Bosanki Samac, and Brcko, Marta, Tumaco, Turbo Oran, Skikda, Tenes Orasje EL SALVADOR AMERICAN SAMOA BRAZIL COMOROS Acajutla, Puerto Cutuco, La Aunu’u, Auasi, Faleosao, Ofu, Belem, Fortaleza, Ikheus, Fomboni, Moroni, Libertad, La Union, Puerto El Pago Pago, Ta’u Imbituba, Manaus, Paranagua, Moutsamoudou Triunfo Porto Alegre, Recife, Rio de ANGOLA Janeiro, Rio Grande, Salvador, CONGO, EQUATORIAL GUINEA Ambriz, Cabinda, Lobito, Luanda Santos, Vitoria DEMOCRATIC Bata, Luba, Malabo Malongo, Mocamedes, Namibe, Porto Amboim, Soyo REPUBLIC OF THE ERITREA BRITISH VIRGIN Banana, Boma, Bukavu, Bumba, Assab, Massawa ANGUILLA ISLANDS Goma, Kalemie, Kindu, Kinshasa, Blowing Point, Road Bay Road Town Kisangani, Matadi, Mbandaka ESTONIA Haapsalu, Kunda, Muuga, ANTIGUAAND BRUNEI CONGO, REPUBLIC Paldiski, Parnu, Tallinn Bandar Seri Begawan, Kuala OF THE BARBUDA Belait, Muara, Tutong -

Threats to the Critically Endangered Christmas

Tirtaningtyas & Hennicke: Threats to the criticallyContributed endangered Papers Christmas Island Frigatebird Fregata andrewsi 137 THREATS TO THE CRITICALLY ENDANGERED CHRISTMAS ISLAND FRIGATEBIRD FREGATA ANDREWSI IN JAKARTA BAY, INDONESIA, AND IMPLICATIONS FOR RECONSIDERING CONSERVATION PRIORITIES FRANSISCA N. TIRTANINGTYAS1 & JANOS C. HENNICKE2,3 1Burung Laut Indonesia, Depok, East Java, 16421, Indonesia ([email protected]) 2Dept. of Ecology and Conservation, University of Hamburg, 20146 Hamburg, Germany 3CEBC-CNRS, 79360 Villiers-en-Bois, France Received 4 November 2014, accepted 26 February 2015 SUMMARY Tirtaningtyas, F.N. & HENNICKE, J.C. 2015. Threats to the critically endangered Christmas Island Frigatebird Fregata andrewsi in Jakarta Bay, Indonesia, and implications for reconsidering conservation priorities. Marine Ornithology 43: 137–140. The Christmas Island Frigatebird Fregata andrewsi is one of the most endangered seabirds in the world. The reasons for its population decline are unknown, but recommended protection measures and management actions focus on the species’ breeding site. Threats to the species away from Christmas Island have received little consideration. Here, we report on several previously undescribed anthropogenic threats to Christmas Island Frigatebirds based on observations in Jakarta Bay, Indonesia: accidental entanglement in fishing gear, as well as capture, poisoning and shooting. Based on these findings, we suggest that it is imperative to reconsider the present management strategies and conservation priorities for the species and to urgently include protection measures away from Christmas Island. Keywords: Christmas Island Frigatebird, Fregata andrewsi, conservation, mortality, anthropogenic threats, Jakarta Bay, Southeast Asia INTRODUCTION Christmas Island Frigatebirds are exposed to threats in Southeast Asian waters, namely in Jakarta Bay, Indonesia, that might contribute The Christmas Island Frigatebird Fregata andrewsi is one of the to the unexplained population decline of the species. -

Endemic Species of Christmas Island, Indian Ocean D.J

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 34 055–114 (2019) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.34(2).2019.055-114 Endemic species of Christmas Island, Indian Ocean D.J. James1, P.T. Green2, W.F. Humphreys3,4 and J.C.Z. Woinarski5 1 73 Pozieres Ave, Milperra, New South Wales 2214, Australia. 2 Department of Ecology, Environment and Evolution, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria 3083, Australia. 3 Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. 4 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, Western Australia 6009, Australia. 5 NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Charles Darwin University, Casuarina, Northern Territory 0909, Australia, Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT – Many oceanic islands have high levels of endemism, but also high rates of extinction, such that island species constitute a markedly disproportionate share of the world’s extinctions. One important foundation for the conservation of biodiversity on islands is an inventory of endemic species. In the absence of a comprehensive inventory, conservation effort often defaults to a focus on the better-known and more conspicuous species (typically mammals and birds). Although this component of island biota often needs such conservation attention, such focus may mean that less conspicuous endemic species (especially invertebrates) are neglected and suffer high rates of loss. In this paper, we review the available literature and online resources to compile a list of endemic species that is as comprehensive as possible for the 137 km2 oceanic Christmas Island, an Australian territory in the north-eastern Indian Ocean. -

Christmas Island Getaway

Christmas Island Getaway www.ditravel.com.au 1300 813 391 Christmas Island Fly-Drive-Stay Duration: 8 days Departs: daily Stay: 7 nights apartment or lodge Travel style: Independent self-drive Booking code: CHRFDS8AZ Call DI Travel on 1300 813 391 Email [email protected] 8 Days Christmas Island Fly-Drive-Stay Getaway About the holiday Christmas Island is an Australian territory in the Indian Ocean, lying south of Java, Indonesia, and 2600 kilometres north west of Perth, Western Australia. What this small, rocky island lacks in size, it more than makes up for with its extraordinary wildlife and spectacular natural wonders! Known as the ‘Galapagos of the Indian Ocean’, Christmas Island is a haven for animals and sea creatures, with close to two-thirds of the island being a protected national park. The island is famous for its red crabs, sea birds, whale sharks and incredible coral reefs. The island’s close proximity to Asia also means there’s a wonderful blend of cultural influences. So there really are few places on our planet like this remote Australian island! Why you’ll love this trip… Indulge in an Australian island escape that’s unlike any other! Dive some of the world’s longest drop-offs & bathe beneath a rainforest waterfall Time it right to witness the amazing annual crab migration at the start of the wet season! Travel Dates Departs regularly* 2021 – 20 April to 15 June, 20 July to 15 September, 10 October to 10 December 2022 – 25 January to 31 March, 20 April to 15 June, 20 July to 15 September, 10 October to 10 December *Departures are subject to confirmation at time of booking. -

Harmonized Reporting Format Trade by Trade Reporting

Harmonized Reporting Format Trade by Trade reporting Introduction The EFC Sub-Committee on EU Government Bonds and Bills Markets agreed on 8 December 2004 to use a common reporting format for primary dealers’ reporting requirements. Debt Management Offices (DMOs) of the euro area should harmonize as much as possible their respective Primary Dealer reporting templates. In concert with the European Primary Dealers Association (EPDA), currently AFME, a Harmonized Reporting Format (HRF) was introduced. Objective A harmonized format for primary dealers’ reporting requirements applicable to all DMOs in the euro area will simplify the production of activity reports by PDs that are active in several euro area markets, thereby offering DMOs the opportunity of obtaining more consistent reports. In order to safeguard the confidentiality of the investor flows reported, each DMO signed a Confidentiality Agreement with their respective PDs with regard to the treatment and the use of the reported information. This Agreement restricts the internal use of the data and ensures that publication of the information if any can only be done in an aggregated format. Technical specifications The objective of these technical specifications is to have one identical reporting format for all PDs and for all DMOs. In this way, PDs can produce the reports electronically and DMOs can electronically extract data from the PDs’ reports in order to analyse their PDs’ activity and/or to produce global reports aggregating the data submitted by PDs individually. The report is submitted to DMOs within thirteen (13) target days following the end of the reported month. All transactions are to be reported in Extensible Markup Language (XML). -

Automatic Exchange of Information (AEI) List of Counterparty Jurisdictions for Your Accounts Booked in British Virgin Islands

ab Automatic Exchange of Information (AEI) List of Counterparty Jurisdictions for your accounts booked in British Virgin Islands Disclaimer UBS AG and its affiliated entities (UBS) does not provide legal or tax advice and this summary does not constitute such advice. UBS strongly recommends all persons considering the information described in this summary obtain appropriate independent legal, tax and other professional advice. This summary is for your information only and is not intended as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any product or other specific services. Although all pieces of information and views expressed in this summary were obtained from sources believed to be reliable and in good faith, neither representation nor warranty, express or implied is made as to its accuracy or completeness. The general explanations included in this summary cannot address your personal situation and financial needs. All information is subject to change without notice. This summary may not be reproduced or copies circulated without prior authority of UBS. The status of a jurisdiction can change at any time. Whilst UBS will use all reasonable endeavors to update this list, there may be changes which become effective before a revised list is published. Information to be reported will depend on the status of the client's jurisdiction(s) of tax residence at the cut-off date for reporting and such status may differ from the status displayed on this list. Information contained in the below table does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever concerning the legal status of any territory or of its authorities. -

Review of Tourism – the Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Christmas Island Indian Ocean Territories Regional Development Organisation – Tourism Review July 2020 Contents

Review of Tourism – The Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Christmas Island Indian Ocean Territories Regional Development Organisation – Tourism Review July 2020 Contents Executive Summary 3 Background 5 Critical Assessment 7 Review Findings 25 Deloitte Indian Ocean Territories Tourism Review 2 Executive Summary Tourism Review of the Indian Ocean Territories Context The Indian Ocean Territories (IOTs) are Australia’s most isolated population. In close proximity The Review Phase of this project included an analysis of tourism literature and current and to South-East Asia and with remarkably diverse landscapes, tourism in the IOTs has the forecast global trends to capture best practice methods to incorporate in the IOTs. This included potential to significantly grow the regional economy, providing sustainable business and reviewing Australian and international jurisdictions to understand how destinations have invested employment opportunities. in tourism to drive economies. Tourism on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands has traditionally been driven by kite surfing during the Deloitte completed a comprehensive consultation process that included seven workshops across trade wind season when accommodation is frequently at capacity. With abundant natural the IOTs, one-on-one meetings with stakeholders on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, one-on-one beauty on land and underwater, a unique cultural identity and scheduled airport runway meetings with stakeholders on Christmas Island, one-on-one meetings with stakeholders in Perth, upgrade, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands are well placed to create a thriving tourism industry. phone interviews and follow-up submissions. The purpose of the Consultation Phase was to understand strengths, weaknesses, barriers to growth and opportunities that can drive tourism in The Christmas Island economy has been dependent on phosphate mining and Government the IOTs and to ensure the future direction of tourism in the IOTs is driven by tourism employed at the Detention Centre. -

Risky Business

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia 5LVN\%XVLQHVV Inquiry into the tender process followed in the sale of the Christmas Island Casino and Resort Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories September 2001 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 2001 ISBN 0 642 78402 7 &RQWHQWV Foreword..............................................................................................................................................vii Membership of the Committee..............................................................................................................ix Terms of reference ...............................................................................................................................xi List of abbreviations............................................................................................................................ xiii Overview..............................................................................................................................................xv List of recommendations.....................................................................................................................xix 1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 1 The inquiry process .................................................................................................. 1 Structure of the report ..............................................................................................