A New Record of the Christmas Island Blind Snake, Ramphotyphlops Exocoeti (Reptilia: Squamata: Typhlopidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Role of Plant Nurseries Introducing Indotyphlops Braminus

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Herpetozoa Jahr/Year: 2017 Band/Volume: 30_1_2 Autor(en)/Author(s): Zamora-Camacho Francisco Javier Artikel/Article: On the role of plant nurseries introducing Indotyphlops braminus (DAUDIN, 1803), in Spain 69-72 All_Short_Notes_(Seiten 59-112):SHORT_NOTE.qxd 07.08.2017 18:41 Seite 11 SHORT NOTE HERPETOZOA 30 (1/2) Wien, 30. Juli 2017 SHORT NOTE 69 On the role of plant nurseries in June 2015, publicly available pro - introducing Indotyphlops braminus fessional e-mail addresses from 403 nursery managers from most provinces of Spain (DAuDiN , 1803), in Spain were compiled; no e-mail address was found from the nursery managers of the A key step in the management of Autonomous cities of ceuta and melilla, human-induced introduction of organisms is and the Province of Zamora. To facilitate release interception or, at least, control identification by non-experts, a description (PERRiNgS et al. 2005), as introductions are of the species was sent to the managers, easier to manage when the potential sources with emphasis on easily distinguishable of propagules are identified ( HulmE 2006). diagnostic characters, as well as two photo - in the case of the typhlopid Flowerpot graphs and one video, along with a ques - Blind snake Indotyphlops braminus (DAu- tionnaire including four questions: (1) Was DiN , 1803), nurseries are widely considered the Flowerpot Blindsnake seen in your nurs - the main (if not the only) propagule reser - ery? (2) if yes, how many individuals? (3) voir and potential vector for introductions When were they seen and (4) were they seen (e. -

MAREN Gaulke Muhliusstrasse 84, 24103 Kiel 1, Germany

Asiatic Research Vol. 6, I June 1995 Herpetolo^ical pp. WW Observations on Arboreality in a Philippine Blind Snake MAREN Gaulke Muhliusstrasse 84, 24103 Kiel 1, Germany Abstract. -Five blind snakes were observed in June 1990 in the rain forests of Sibutu Island in the Sulu Archipelago, Philippines. Contrary to the usually fossorial habits of typhlopids, Ramphotyphlops suluensis (Taylor, 1918) shows arboreal habits. It climbed through trees at night using the prehensile tail and hindbody. When caught they extruded a strong smelling liquid from their cloaca. Relatively long tails are found in some other rain forest dwelling typhlopids, which may also have arboreal habits. Key words: Reptilia, Ophidia, Typhlopidae, Ramphotyphlops suluensis, Philippines, ecology. and the relative humidity between 70 and Introduction 95%. Little is known of the behavior of blind The nomenclatural history and taxonomy snakes (Typhlopidae). Information is of the typhlopids observed and caught on normally generalized and consists of little Sibutu is discussed in Gaulke (in press), more than that typhlopids are small, where the species, previously synonymized burrowing snakes, which live in decaying with Ramphotyphlops olivaceus (Gray, logs, humus and leaf litter, and feed mainly 1845), is revalidated. Ramphotyphlops on ants and termites, especially their grubs, suluensis reaches a length of approximately pupae and eggs (e. g. Taylor, 1922; 40 cm, the eyes are distinctive, and the tail is Loveridge, 1946; Gruber, 1980). more than twice as long as broad. The dorsal side is gray, the ventral side is cream, This gap in observations is certainly due with bright white scales along the median to a number of different factors. -

Unsustainable Food Systems Threaten Wild Crop and Dolphin Species

INTERNATIONAL PRESS RELEASE Embargoed until: 07:00 GMT (16:00 JST) 5 December 2017 Elaine Paterson, IUCN Media Relations, t+44 1223 331128, email [email protected] Goska Bonnaveira, IUCN Media Relations, m +41 792760185, email [email protected] [In Japan] Cheryl-Samantha MacSharry, IUCN Media Relations, t+44 1223 331128, email [email protected] Download photographs here Download summary statistics here Unsustainable food systems threaten wild crop and dolphin species Tokyo, Japan, 5 December 2017 (IUCN) – Species of wild rice, wheat and yam are threatened by overly intensive agricultural production and urban expansion, whilst poor fishing practices have caused steep declines in the Irrawaddy Dolphin and Finless Porpoise, according to the latest update of The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™. Today’s Red List update also reveals that a drying climate is pushing the Ringtail Possum to the brink of extinction. Three reptile species found only on an Australian island – the Christmas Island Whiptail-skink, the Blue- tailed Skink (Cryptoblepharus egeriae) and the Lister’s Gecko – have gone extinct, according to the update. But in New Zealand, conservation efforts have improved the situation for two species of Kiwi. “Healthy, species-rich ecosystems are fundamental to our ability to feed the world’s growing population and achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goal 2 – to end hunger by 2030,” says IUCN Director General Inger Andersen. “Wild crop species, for example, maintain genetic diversity of agricultural crops -

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites (Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, Upper Marikina-Kaliwa Forest Reserve, Bago River Watershed and Forest Reserve, Naujan Lake National Park and Subwatersheds, Mt. Kitanglad Range Natural Park and Mt. Apo Natural Park) Philippines Biodiversity & Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy & Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) 23 March 2015 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. The Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience Program is funded by the USAID, Contract No. AID-492-C-13-00002 and implemented by Chemonics International in association with: Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites Philippines Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) Program Implemented with: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Other National Government Agencies Local Government Units and Agencies Supported by: United States Agency for International Development Contract No.: AID-492-C-13-00002 Managed by: Chemonics International Inc. in partnership with Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) 23 March -

Endemic Species of Christmas Island, Indian Ocean D.J

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 34 055–114 (2019) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.34(2).2019.055-114 Endemic species of Christmas Island, Indian Ocean D.J. James1, P.T. Green2, W.F. Humphreys3,4 and J.C.Z. Woinarski5 1 73 Pozieres Ave, Milperra, New South Wales 2214, Australia. 2 Department of Ecology, Environment and Evolution, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria 3083, Australia. 3 Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. 4 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, Western Australia 6009, Australia. 5 NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Charles Darwin University, Casuarina, Northern Territory 0909, Australia, Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT – Many oceanic islands have high levels of endemism, but also high rates of extinction, such that island species constitute a markedly disproportionate share of the world’s extinctions. One important foundation for the conservation of biodiversity on islands is an inventory of endemic species. In the absence of a comprehensive inventory, conservation effort often defaults to a focus on the better-known and more conspicuous species (typically mammals and birds). Although this component of island biota often needs such conservation attention, such focus may mean that less conspicuous endemic species (especially invertebrates) are neglected and suffer high rates of loss. In this paper, we review the available literature and online resources to compile a list of endemic species that is as comprehensive as possible for the 137 km2 oceanic Christmas Island, an Australian territory in the north-eastern Indian Ocean. -

Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L

CIR1462 Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L. Casler, Elise V. Pearlstine, Frank J. Mazzotti, and Kenneth L. Krysko2 Background snakes are often escapees or are released deliberately and illegally by owners who can no longer care for them. Snakes are members of the vertebrate order Squamata However, there has been no documentation of these snakes (suborder Serpentes) and are most closely related to lizards breeding in the EAA (Tennant 1997). (suborder Sauria). All snakes are legless and have elongated trunks. They can be found in a variety of habitats and are able to climb trees; swim through streams, lakes, or oceans; Benefits of Snakes and move across sand or through leaf litter in a forest. Snakes are an important part of the environment and play Often secretive, they rely on scent rather than vision for a role in keeping the balance of nature. They aid in the social and predatory behaviors. A snake’s skull is highly control of rodents and invertebrates. Also, some snakes modified and has a great degree of flexibility, called cranial prey on other snakes. The Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis kinesis, that allows it to swallow prey much larger than its getula floridana), for example, prefers snakes as prey and head. will even eat venomous species. Snakes also provide a food source for other animals such as birds and alligators. Of the 45 snake species (70 subspecies) that occur through- out Florida, 23 may be found in the Everglades Agricultural Snake Conservation Area (EAA). Of the 23, only four are venomous. The venomous species that may occur in the EAA are the coral Loss of habitat is the most significant problem facing many snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius), Florida cottonmouth wildlife species in Florida, snakes included. -

A Taxonomic Framework for Typhlopid Snakes from the Caribbean and Other Regions (Reptilia, Squamata)

caribbean herpetology article A taxonomic framework for typhlopid snakes from the Caribbean and other regions (Reptilia, Squamata) S. Blair Hedges1,*, Angela B. Marion1, Kelly M. Lipp1,2, Julie Marin3,4, and Nicolas Vidal3 1Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301, USA. 2Current address: School of Dentistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7450, USA. 3Département Systématique et Evolution, UMR 7138, C.P. 26, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05, France. 4Current address: Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. *Corresponding author ([email protected]) Article registration: http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:47191405-862B-4FB6-8A28-29AB7E25FBDD Edited by: Robert W. Henderson. Date of publication: 17 January 2014. Citation: Hedges SB, Marion AB, Lipp KM, Marin J, Vidal N. 2014. A taxonomic framework for typhlopid snakes from the Caribbean and other regions (Reptilia, Squamata). Caribbean Herpetology 49:1–61. Abstract The evolutionary history and taxonomy of worm-like snakes (scolecophidians) continues to be refined as new molec- ular data are gathered and analyzed. Here we present additional evidence on the phylogeny of these snakes, from morphological data and 489 new DNA sequences, and propose a new taxonomic framework for the family Typhlopi- dae. Of 257 named species of typhlopid snakes, 92 are now placed in molecular phylogenies along with 60 addition- al species yet to be described. Afrotyphlopinae subfam. nov. is distributed almost exclusively in sub-Saharan Africa and contains three genera: Afrotyphlops, Letheobia, and Rhinotyphlops. Asiatyphlopinae subfam. nov. is distributed in Asia, Australasia, and islands of the western and southern Pacific, and includes ten genera:Acutotyphlops, Anilios, Asiatyphlops gen. -

Science for Saving Species Research Update Project 2.3.2 Options Beyond Captivity for Two Critically Endangered Christmas Island Reptiles

Science for Saving Species Research Update Project 2.3.2 Options beyond captivity for two critically endangered Christmas Island reptiles Conservation options for Christmas Island’s blue-tailed skinks Project Overview Introduced predators The blue-tailed skink Several introduced predators (Cryptoblepharus egeriae) threaten these lizard species, and and Lister’s gecko (Lepidodactylus were likely to have significantly listeri) are two endemic reptiles contributed to their extinction in to Christmas Island that are the wild. The wolf snake (Lycodon now presumed to be extinct in capucinus) and giant centipede the Wild. Both were once (Scolopendra subspinipes) are two common on the Island, however such species, and pose ongoing both declined rapidly from the threats to reintroduced wild 1980s, and by 2012 both had populations of skinks and geckos. vanished from the wild. The wolf snake was introduced Fortunately, in 2009 and early to Christmas Island in the 1980s 2010, Parks Australia, with the and is now found across the entire help of Perth Zoo, captured 66 island. On Christmas Island, the wolf blue-tailed skinks and 43 Lister’s snake is known to threaten native geckos to establish captive reptiles via predation. It has also breeding populations on been implicated in the extinction Christmas Island and at Taronga of the Christmas Island pipistrelle Zoo. Captive breeding has (Pipistrellus murrayi). circumvented extinction in Giant centipedes have been the short term, with both present since European settlement captive populations now over of the island in the late 1880s. 1000individuals. However, They predate on a range of native the facilities on Christmas Island species, including native reptiles Image: Renata De Jonge, Parks Australia have reached carrying capacity, like the blue-tailed skink and Blue-tailed skinks within a breeding and there is strong interest in Lister’s gecko. -

Threatened Species Nomination Form

Invitation to comment on EPBC Act nomination to list in the Critically Endangered category: Emoia nativitatis (Forest skink) Anyone may nominate a native species, ecological community or threatening process for listing under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). You are invited to provide comment on the attached nomination to assist the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) with its assessment of whether Emoia nativitatis (Forest skink) is eligible for inclusion in the EPBC Act list of threatened species in the critically endangered category. The Committee welcomes the views of experts, stakeholders and the general public on nominations to further inform its nomination assessment process. In order to determine if a species, ecological community or threatening process is eligible for listing under the EPBC Act, a rigorous scientific assessment of its status is undertaken. These assessments are undertaken by the Committee to determine if an item is eligible for listing against a set of criteria as set out in the guidelines for nominating and assessing threatened species and ecological communities, and threatening processes. These are available at: http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/nominations.html To assist in this matter, the Committee has identified a series of specific questions on which it seeks particular guidance (Part A). The nomination for this item is provided in Part B. Individual nominations may vary considerably in quality. Therefore in addition to the information presented in the nomination, the Committee also takes into account published data and considers other information received when it prepares its advice for the Minister. Responses to this consultation will be provided in full to the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. -

Zootaxa,A Review of East and Central African Species of Letheobia Cope

Zootaxa 1515: 31–68 (2007) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2007 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A review of East and Central African species of Letheobia Cope, revived from the synonymy of Rhinotyphlops Fitzinger, with descriptions of five new species (Serpentes: Typhlopidae) DONALD. G. BROADLEY1 & VAN WALLACH2 1Research Associate, Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe; mailing address –Biodiversity Foundation for Africa, P.O. Box FM 730, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. E-mail: [email protected] 2Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] Table of contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................................. 32 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................32 Materials and methods ......................................................................................................................................................32 Character analysis .............................................................................................................................................................33 Systematic account ............................................................................................................................................................38 -

Northern Territory NT Page 1 of 204 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region Northern Territory, Northern Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

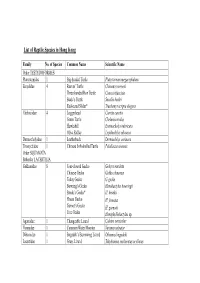

List of Reptile Species in Hong Kong

List of Reptile Species in Hong Kong Family No. of Species Common Name Scientific Name Order TESTUDOFORMES Platysternidae 1 Big-headed Turtle Platysternum megacephalum Emydidae 4 Reeves’ Turtle Chinemys reevesii Three-banded Box Turtle Cuora trifasciata Beale’s Turtle Sacalia bealei Red-eared Slider* Trachemys scripta elegans Cheloniidae 4 Loggerhead Caretta caretta Green Turtle Chelonia mydas Hawksbill Eretmochelys imbricata Olive Ridley Lepidochelys olivacea Dermochelyidae 1 Leatherback Dermochelys coriacea Trionychidae 1 Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle Pelodiscus sinensis Order SQUAMATA Suborder LACERTILIA Gekkonidae 8 Four-clawed Gecko Gehyra mutilata Chinese Gecko Gekko chinensis Tokay Gecko G. gecko Bowring’s Gecko Hemidactylus bowringii Brook’s Gecko* H. brookii House Gecko H. frenatus Garnot’s Gecko H. garnotii Tree Gecko Hemiphyllodactylus sp. Agamidae 1 Changeable Lizard Calotes versicolor Varanidae 1 Common Water Monitor Varanus salvator Dibamidae 1 Bogadek’s Burrowing Lizard Dibamus bogadeki Lacertidae 1 Grass Lizard Takydromus sexlineatus ocellatus Scincidae 11 Chinese Forest Skink Ateuchosaurus chinensis Chinese Skink Eumeces chinensis chinensis Five-striped Blue-tailed Skink E. elegans Blue-tailed Skink E. quadrilineatus Vietnamese Five-lined Skink E. tamdaoensis Long-tailed Skink Mabuya longicaudata Slender Forest Skink Scincella modesta Reeve’s Smooth Skink S. reevesii Indian Forest Skink Sphenomorphus indicus Brown Forest Skink S. incognitus Chinese Waterside Skink Tropidophorus sinicus Order SQUAMATA Suborder SERPENTES Typhlopidae 3 Lazell’s Blind Snake Typhlops lazelli White-headed Blind Snake Ramphotyphlops albiceps Common Blind Snake R. braminus Boidae 1 Burmese Python Python molurus bivittatus Colubridae 34 Rufous Burrowing Snake Achalinus rufescens Jade Vine Snake Ahaetulla prasina medioxima Mountain Keelback Amphiesma atemporale White-browed Keelback A. boulengeri Buff-striped Keelback A.