8-Sumita Saha.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hindu America

HINDU AMERICA Revealing the story of the romance of the Surya Vanshi Hindus and depicting the imprints of Hindu Culture on tho two Americas Flower in the crannied wall, I pluck you out of the crannies, I hold you here, root and all, in my hand. Little flower— but if I could understand What you arc. root and all. and all in all, I should know what God and man is — /'rimtjihui' •lis far m the deeps of history The Voice that speaVeth clear. — KiHtf *Wf. The IIV./-SM#/. CHAMAN LAL NEW BOOK CO HORNBY ROAD, BOMBAY COPY RIGHT 1940 By The Same Author— SECRETS OF JAPAN (Three Editions in English and Six translations). VANISHING EMPIRE BEHIND THE GUNS The Daughters of India Those Goddesses of Piety and Sweetness Whose Selflessness and Devotion Have Preserved Hindu Culture Through the Ages. "O Thou, thy race's joy and pride, Heroic mother, noblest guide. ( Fond prophetess of coming good, roused my timid mood.’’ How thou hast |! THANKS My cordial chaoks are due to the authors and the publisher* mentioned in the (eat for (he reproduction of important authorities from their books and loumils. My indchtcdih-ss to those scholars and archaeologists—American, European and Indian—whose works I have consulted and drawn freely from, ts immense. Bur for the results of list investigations made by them in their respective spheres, it would have been quite impossible for me to collect materials for this book. I feel it my duty to rhank the Republican Governments of Ireland and Mexico, as also two other Governments of Europe and Asia, who enabled me to travel without a passport, which was ruthlessly taken away from me in England and still rests in the archives of the British Foreign Office, as a punishment for publication of my book the "Vanishing Empire!" I am specially thankful to the President of the Republic of Mexico (than whom there is no greater democrat today)* and his Foreign Minister, Sgr. -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

CIN Company Name 23-JUL-2012 First Name Middle Name Last

CIN L32102KA1945PLC020800 Company Name WIPRO LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 23-JUL-2012 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 3333020 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of matured deposit 0 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husb Father/Husba Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of and First nd Middle Last Name Securities Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF Name Name (DD-MON-YYYY) R RAVI KUMAR S RAGHAVENDERRAO WIPRO LTD DUPARC TRINITYINDIA 10TH FLOOR KARNATAKA 17 M G ROAD BANGALORE BANGALORE 560001 WPL005770 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid25000.00 dividend 20-JUL-2018 TAPAN BHAT DATTARAM G BHAT F-2 ROYAL OAK APTS 136INDIA DEFENCE COLONY KARNATAKA 6TH MAIN 4TH CROSS BANGALOREH A L IIND STAGE INDIRANAGAR BANGALORE 560038 WPL005453 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid20000.00 dividend 20-JUL-2018 P PURUSHOTTAM NA NO 3 VASUGI STREET INDIAOPP STEADFORD TAMILHOSPITAL NADU AMBATTUR MADRAS CHENNAI 600053 WPL002504 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid11200.00 dividend 20-JUL-2018 SANJEEV KUMAR ARORA NA 20 A/1 BANK ENCLAVEINDIA RAJOURI GARDEN DELHI NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110027 WPL950043 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend64.00 20-JUL-2018 DINESH RAJ GUPTA NA 16 B TAGORE ROAD ADARSHINDIA NAGAR DELHI DELHI NEW DELHI 110033 WPL950093 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend332.00 -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Human Sacrifice in Colonial Central India: Myth, Agency And

Edinburgh Research Explorer Human Sacrifice in Colonial Central India: Myth, Agency and Representation Citation for published version: Bates, C 2006, Human Sacrifice in Colonial Central India: Myth, Agency and Representation. in C Bates (ed.), Beyond Representation: constructions of identity in colonial and postcolonial India . OUP India. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Beyond Representation: constructions of identity in colonial and postcolonial India General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 From C. Bates (ed.), Beyond Representations: colonial and postcolonial constructions of Indian identity (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006) Chapter 2. Human Sacrifice in Colonial Central India: Myth, Agency and Representation Crispin Bates The sanguinary nature of early contacts with the tribals, or adivasis, of central India did not bode well for their future reputation. The first expedition into Bastar by Captain Blunt, in 1795, was attacked and expelled from the country, from which experience may be traced some of the more fearful accounts of the savagery of tribal Gonds.1 The already established reputations of the predatory Bhils of Gujarat and the rebellious Santhals and Kols of Bihar also served to colour the expectations of early travellers in central India. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Tea Board 14, B

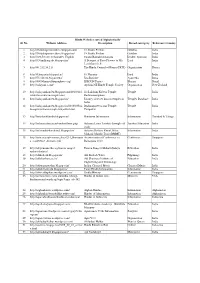

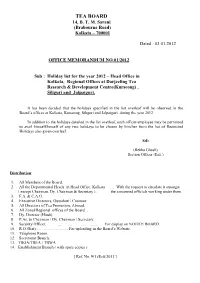

TEA BOARD 14, B. T. M. Sarani (Brabourne Road) Kolkata – 700001 Dated : 03.01.2012 OFFICE MEMORANDUM NO.01/2012 Sub : Holiday list for the year 2012 – Head Office in Kolkata, Regional Offices at Darjeeling Tea Research & Development Centre(Kurseong) , Siliguri and Jalpaiguri. It has been decided that the holidays specified in the list overleaf will be observed in the Board’s offices at Kolkata, Kurseong, Siliguri and Jalpaiguri during the year 2012. In addition to the holidays detailed in the list overleaf, each officer/employee may be permitted to avail himself/herself of any two holidays to be chosen by him/her from the list of Restricted Holidays also given overleaf. Sd/- (Rekha Ghosh) Section Officer (Estt.) Distribution: 1. All Members of the Board. 2. All the Departmental Heads in Head Office, Kolkata … With the request to circulate it amongst ( except Chairman, Dy. Chairman & Secretary ). the concerned officials working under them. 3. F.A. & C.A.O. 4. Executive Directors, Guwahati / Coonoor. 5. All Directors of Tea Promotion, Abroad. 6. All Zonal/Regional offices of the Board . 7. Dy. Director (Hindi). 8. P.As. to Chairman / Dy. Chairman / Secretary. 9. Security Officer. …. …. …. ….. For display on NOTICE BOARD. 10. R.O.(Stat)…………………….For uploading in the Board’s Website. 11. Telephone Room. 12. Secretariat Branch. 13. TBOA/TBEA / TBWA 14. Establishment Branch ( with spare copies ) . [ Ref. No. 9(1)/Estt/2011 ] ( 2 ) HOLIDAY LIST FOR THE CALENDER YEAR 2012 IN RESPECT OF BOARD’S HEAD OFFICE IN KOLKATA, REGIONAL OFFICES AT KURSEONG, SILIGURI & JALPAIGURI Sl. D a t e D a y Name of the Festival No. -

Utilization of Natural Resources in Tribal Life

IOSR Journal of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 26, Issue 5, Series 7 (May. 2021) 34-40 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Utilization of Natural Resources in Tribal Life Dibyajyoti Ganguly Guest Lecturer, Dept. of Anthropology, Ramsaday College, West Bengal, India Dr. Palash Chandra Coomar Former Joint Director of Census Operations, Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India Contact Address: 94/4, P Road, Howrah, P.O. – Netajigarh, P.S. – Dasnagar, Pin – 711108, Howrah, West Bengal, India --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 06-05-2021 Date of Acceptance: 19-05-2021 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION It has generally been accepted that close relation with nature and living within its proximity used to give tribe a distinctive identity of its own as reflected in its thoughts and beliefs, activities and customary practices. But with the spread of education and rapid expansion of modernization process, the tribal population slowly but surely is being alienated from the nature. The tribal people used to derive nourishment, both materially and symbolically, from the nature and rely on it so heavily that it was thought to be a cause of techno- economic backwardness prevailing among them. It has become a stark reality of tribal life, particularly in those cases where life of tribals is intricately linked with nature as provider and protector of their life ways. Nature provides them food, fodder, fuel and makes available a rich collection of medicinal plants and all other basic requirements needed for survival. Hence it is no exaggeration to say that such tribals giving the impression of an ‘eco system people’ are the real friends of nature in true sense of the term. -

2020 Calendar

SLOPELAND PUBLIC SCHOOL ACADEMIC CALENDAR, 2020-2021 January (2020) DATE DETAILS Sun Mon Tue Wed Thur Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 1 New Year Day 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 15 New Session for LKG to Class 10 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 26 Republic Day 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 February (2020) 2 18th Foundation Day of Slopeland Public School Sun Mon Tue Wed Thur Fri Sat 7 Final Exam for Class 11 1 15 Lui ngai Ni 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 23 Parents Teachers Meet for Class 10 & 12 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 March (2020) 9 Yaosang (Hoil) Sun Mon Tue Wed Thur Fri Sat 19 New session 2020-21 for class 12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 25 Cheiraoba 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 April (2020) 10 Good Friday Sun Mon Tue Wed Thur Fri Sat 13 Charak Puja Chiraoba 1 2 3 4 23 Khongjom Day 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 May (2020) 1 May Day Sun Mon Tue Wed Thur Fri Sat 17 Parents Teacher meet 1 2 25 Eid Ui Fitr / Ramzan Id 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 26 First Team Exam forLKG to 10 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 June (2020) 8 to 30 Summer Vacantion (There will be no Summer Sun Mon Tue Wed Thur Fri Sat vacation for class 12 Students) 1 2 3 4 5 6 23 Rath Yatra 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 July (2020) S 1 chool Re-Open (New Session for class 11 Sun Mon Tue Wed Thur Fri Sat SC/Art/Com) 1 2 3 4 6 Result out for 1st Term 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 10 First Term for Class XII 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 13 Health Assessment for the Student 19 20 -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. No. Reference Broad catergory Website Address Description Country 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/m Hindu Kush odern/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temp Hindu Temples of Kabul les_of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?modul Hindu Temples of Afaganistan e=pluspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint &title=Hindu%20Temples%20in%20Afg hanistan%20.html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

PUJA WORD Search

New Arrivals Aananya Daughter of Reema and Tapas Das Lavkush Son of Miki and Badal Sarkar Durga Puja 2009 www.batj.org 105 My Dubai Trip Sneha Kundu, Grade I ast winter, I went to my cousin’s Lhouse in Dubai. There I went to Desert. It is full of sand. I could not see anything without sand. Everywhere it much fun but sometimes I was sand and sand! got scared. I tried to make a sand house there. There I saw Camel and I went on Desert Safari. It is a I cannot forget that trip. car ride in desert. It was very I want to go there again. g PUJA WORD Search WORDS: 1. PUJA 10. LION 2. DHAK 11. PEACOCK 3. DURGA 12. MOUSE 4. SARASWATI 13. SWAN 5. LAXMI 14. OWL 6. KARTIK 15. SINDUR 7. GANESH 16. DHUP 8. MAHISASHUR 17. SHANKH 9. SHIVA M G S H A N K H L M S A R A S W A T I I D N H G H A R P O T K E A I R A T I N A C S L R S H I V A S O H W D H A K D L I C M O U S E S W A N A G A R B A T H J D E M K G D H U P U U P O L A X M I S P R 106 Anjali liens Nishant Chanda, Grade III “Mom can I buy this book pack” I asked “Get up and go to work.” my mom.