Chapter Iii the People Growth of Population Census of 1901

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom in West Bengal Revised

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Freedom and its Enemies: Politics of Transition in West Bengal, 1947-1949 * Sekhar Bandyopadhyay Victoria University of Wellington I The fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence became an occasion for the publication of a huge body of literature on post-colonial India. Understandably, the discussion of 1947 in this literature is largely focussed on Partition—its memories and its long-term effects on the nation. 1 Earlier studies on Partition looked at the ‘event’ as a part of the grand narrative of the formation of two nation-states in the subcontinent; but in recent times the historians’ gaze has shifted to what Gyanendra Pandey has described as ‘a history of the lives and experiences of the people who lived through that time’. 2 So far as Bengal is concerned, such experiences have been analysed in two subsets, i.e., the experience of the borderland, and the experience of the refugees. As the surgical knife of Sir Cyril Ratcliffe was hastily and erratically drawn across Bengal, it created an international boundary that was seriously flawed and which brutally disrupted the life and livelihood of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis, many of whom suddenly found themselves living in what they conceived of as ‘enemy’ territory. Even those who ended up on the ‘right’ side of the border, like the Hindus in Murshidabad and Nadia, were apprehensive that they might be sacrificed and exchanged for the Hindus in Khulna who were caught up on the wrong side and vehemently demanded to cross over. -

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXXI NO. 5 DECEMBER - 2014 MADHUSUDAN PADHI, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary RANJIT KUMAR MOHANTY, O.A.S, ( SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Shrikshetra, Matha and its Impact Subhashree Mishra ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 India International Trade Fair - 2014 : An Overview Smita Kar ... 7 Mo Kahani' - The Memoir of Kunja Behari Dash : A Portrait Gallery of Pre-modern Rural Odisha Dr. Shruti Das ... 10 Protection of Fragile Ozone Layer of Earth Dr. Manas Ranjan Senapati ... 17 Child Labour : A Social Evil Dr. Bijoylaxmi Das ... 19 Reflections on Mahatma Gandhi's Life and Vision Dr. Brahmananda Satapathy ... 24 Christmas in Eternal Solitude Sonril Mohanty ... 27 Dr. B.R. Ambedkar : The Messiah of Downtrodden Rabindra Kumar Behuria ... 28 Untouchable - An Antediluvian Aspersion on Indian Social Stratification Dr. Narayan Panda ... 31 Kalinga, Kalinga and Kalinga Bijoyini Mohanty .. -

Hindu America

HINDU AMERICA Revealing the story of the romance of the Surya Vanshi Hindus and depicting the imprints of Hindu Culture on tho two Americas Flower in the crannied wall, I pluck you out of the crannies, I hold you here, root and all, in my hand. Little flower— but if I could understand What you arc. root and all. and all in all, I should know what God and man is — /'rimtjihui' •lis far m the deeps of history The Voice that speaVeth clear. — KiHtf *Wf. The IIV./-SM#/. CHAMAN LAL NEW BOOK CO HORNBY ROAD, BOMBAY COPY RIGHT 1940 By The Same Author— SECRETS OF JAPAN (Three Editions in English and Six translations). VANISHING EMPIRE BEHIND THE GUNS The Daughters of India Those Goddesses of Piety and Sweetness Whose Selflessness and Devotion Have Preserved Hindu Culture Through the Ages. "O Thou, thy race's joy and pride, Heroic mother, noblest guide. ( Fond prophetess of coming good, roused my timid mood.’’ How thou hast |! THANKS My cordial chaoks are due to the authors and the publisher* mentioned in the (eat for (he reproduction of important authorities from their books and loumils. My indchtcdih-ss to those scholars and archaeologists—American, European and Indian—whose works I have consulted and drawn freely from, ts immense. Bur for the results of list investigations made by them in their respective spheres, it would have been quite impossible for me to collect materials for this book. I feel it my duty to rhank the Republican Governments of Ireland and Mexico, as also two other Governments of Europe and Asia, who enabled me to travel without a passport, which was ruthlessly taken away from me in England and still rests in the archives of the British Foreign Office, as a punishment for publication of my book the "Vanishing Empire!" I am specially thankful to the President of the Republic of Mexico (than whom there is no greater democrat today)* and his Foreign Minister, Sgr. -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

CIN Company Name 23-JUL-2012 First Name Middle Name Last

CIN L32102KA1945PLC020800 Company Name WIPRO LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 23-JUL-2012 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 3333020 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of matured deposit 0 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husb Father/Husba Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of and First nd Middle Last Name Securities Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF Name Name (DD-MON-YYYY) R RAVI KUMAR S RAGHAVENDERRAO WIPRO LTD DUPARC TRINITYINDIA 10TH FLOOR KARNATAKA 17 M G ROAD BANGALORE BANGALORE 560001 WPL005770 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid25000.00 dividend 20-JUL-2018 TAPAN BHAT DATTARAM G BHAT F-2 ROYAL OAK APTS 136INDIA DEFENCE COLONY KARNATAKA 6TH MAIN 4TH CROSS BANGALOREH A L IIND STAGE INDIRANAGAR BANGALORE 560038 WPL005453 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid20000.00 dividend 20-JUL-2018 P PURUSHOTTAM NA NO 3 VASUGI STREET INDIAOPP STEADFORD TAMILHOSPITAL NADU AMBATTUR MADRAS CHENNAI 600053 WPL002504 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid11200.00 dividend 20-JUL-2018 SANJEEV KUMAR ARORA NA 20 A/1 BANK ENCLAVEINDIA RAJOURI GARDEN DELHI NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110027 WPL950043 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend64.00 20-JUL-2018 DINESH RAJ GUPTA NA 16 B TAGORE ROAD ADARSHINDIA NAGAR DELHI DELHI NEW DELHI 110033 WPL950093 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend332.00 -

DEPARTMENT of FOLKLORE University of Kalyani

DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE University of Kalyani COURSE CURRICULA OF M.A. IN FOLKLORE (Two- years Master’s Degree Programme under the Scheme of CBCS) Session: 2017-2018 and onwards As recommended by the Post Graduate Board of Studies (PGBoS) in Folklore in the meeting held on May 05, 2017 OPERATIONAL ASPECTS A. Timetable: 1) Class-hour will be of 1 hour and the time schedule of classes should be from 10.30 a.m. to 5.00 p.m. with 30 minutes lunch-break during 1.30 to 2.00 p.m., from Monday to Friday. Thus there shall be maximum 6 classes a day. 2) Normal 16 class-hours in a week may be kept for direct class instructions. The remaining 14 hours in a week shall be kept for Tutorial, Dissertation, Seminar, Assignments, Special Classes, holding class-tests etc. as may be required for the course. B. Course-papers and Allocation of Class-Hours per Course: 1) For evaluation purposes, each course shall be of 100 marks and for each course of 100 marks total number of direct instruction hours (theory/practical/field-training) shall be 48 hours. 2) The full course in 4 semesters shall be of total 1600 marks with total 16 courses (Fifteen Core Courses & One Open Course). In each semester, the course work shall be for 4 courses of total 400 marks. C. Credit Specification of the Course Curricula: M.A. Course in Folklore shall comprise 4 semesters. Each semester shall have 4 courses. In all, there shall be 16 courses of 4 credits each. -

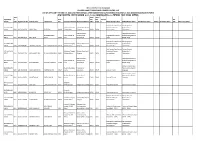

Eforms Publication of SEM-VI, 2021 on 7-9-2021.Xlsx

THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN COLLEGE NAME- TARAKESWAR DEGREE COLLEGE- 415 LIST OF APPLICANT FOR SEM -VI, 2020 AND THEIR DETAILS AFTER SUBMITTING BA/BCOM/BSC (H/G) SEM-VI, 2021 ONLINE EXAMINATION FORM (যারা অনলাইন পেম কেরেছ ৯/০৭/২০২১ (বার) রাত ৮.০০ িমিনেটর মেধ তােদর তািলকা) Cours Hons/ Hons/ Application e Hons Gen Gen Gen Sub- SEC Seq No Code Registration No Student Name Father Name Sub Honours Sub CC-13 Honours Sub CC-14 Sub-1 Sub-2 3 DSE-3/1B Topic Name DSE-4/2BTopic Name DSE-3B Topic Name GE Sub GE-2 Topic Name Sub SEC-4 Topic Name Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 29030 BAH 201501064828 SRIBAS BAG DILIP BAG BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 DIPENDRA NATH Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and Stage Demonstration - Rabindra Sangeet and 33874 BAH 201501070379 ADITI BERA BERA MUCH Drut Nrityanatya MUCH MUCH Khyal Bengali Song Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28925 BAH 201601067467 CHANDRA SANTRA ASIT KUMAR SANTRA BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28717 BAH 201601073761 MADHUMITA BALI SHYAMSUNDAR BALI BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and -

Howrah, West Bengal

Howrah, West Bengal 1 Contents Sl. No. Page No. 1. Foreword ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 2. District overview ……………………………………………………………………………… 5-16 3. Hazard , Vulnerability & Capacity Analysis a) Seasonality of identified hazards ………………………………………………… 18 b) Prevalent hazards ……………………………………………………………………….. 19-20 c) Vulnerability concerns towards flooding ……………………………………. 20-21 d) List of Vulnerable Areas (Village wise) from Flood ……………………… 22-24 e) Map showing Flood prone areas of Howrah District ……………………. 26 f) Inundation Map for the year 2017 ……………………………………………….. 27 4. Institutional Arrangements a) Departments, Div. Commissioner & District Administration ……….. 29-31 b) Important contacts of Sub-division ………………………………………………. 32 c) Contact nos. of Block Dev. Officers ………………………………………………… 33 d) Disaster Management Set up and contact nos. of divers ………………… 34 e) Police Officials- Howrah Commissionerate …………………………………… 35-36 f) Police Officials –Superintendent of Police, Howrah(Rural) ………… 36-37 g) Contact nos. of M.L.As / M.P.s ………………………………………………………. 37 h) Contact nos. of office bearers of Howrah ZillapParishad ……………… 38 i) Contact nos. of State Level Nodal Officers …………………………………….. 38 j) Health & Family welfare ………………………………………………………………. 39-41 k) Agriculture …………………………………………………………………………………… 42 l) Irrigation-Control Room ………………………………………………………………. 43 5. Resource analysis a) Identification of Infrastructures on Highlands …………………………….. 45-46 b) Status report on Govt. aided Flood Shelters & Relief Godown………. 47 c) Map-showing Govt. aided Flood -

IJRESS Volume 6, Issue 2

International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences (IJRESS) Available online at: http://euroasiapub.org Vol. 7 Issue 7, July- 2017 ISSN(o): 2249-7382 | Impact Factor: 6.939 | Thomson Reuters Researcher ID: L-5236-2015 Dissemination of social messages by Folk Media – A case study through folk drama Bolan of West Bengal Mr. Sudipta Paul Research Scholar, Department of Mass Communication & Videography, Rabindra Bharati University Abstract: In the vicinity of folk-culture, folk drama is of great significance because it reflects the society by maintaining a non-judgemental stance. It has a strong impact among the audience as the appeal of Bengali folk-drama is undeniable. ‘Bolan’ is a traditional folk drama of Bengal which is mainly celebrated in the month of ‘Chaitra’ (march-april). Geographically, it is prevalent in the mid- northern rural and semi-urban regions of Bengal (Rar Banga area) – mainly in Murshidabad district and some parts of Nadia, Birbhum and Bardwan districts. Although it follows the theatrical procedures, yet it is different from the same because it has no female artists. The male actors impersonate as females and play the part. Like other folk drama ‘Bolan’ is in direct contact with the audience and is often interacted and modified by them. Primarily it narrates mythological themes but now-a-days it narrates contemporary socio-politico-economical and natural issues. As it is performed different contemporary issues of immense interest audiences is deeply integrated with it and try to assimilate the messages of social importance from it. And in this way Mass (traditional) media plays an important role in shaping public opinion and forming a platform of exchange between the administration and the people they serve. -

January 2018

UNIQUE IAS ACADEMY- JANUARY 2018 01st January 2018 1. Nepal Bans Solo Climbing on Mount Everest i. Nepal has banned solo climbers from scaling its mountains, including Mount Everest, in a bid to reduce accidents. ii. The new safety regulations also prohibit double amputee and blind climbers from attempting to reach the summit of the world's highest peak without a valid medical certificate. Static/Current Takeaways Important for IBPS Clerk Mains 2017 Exam- Avtar Singh Cheema was the first Indian to climb Mount Everest successfully. Mount Everest is the tallest Mountain (by Elevation) in the world. 2. Israel Withdraws from UNESCO i. Israel has filed notice to withdraw from the UNESCO alongside the United States. Israel has blasted UNESCO in recent years over the organisation's criticism of Israel's occupation of East Jerusalem and its decision to grant full membership to Palestine in 2011. ii. Israel was the member of UNESCO since 1949. Both Israel and the US have filed its own withdrawal notice in October 2017. Static/Current Takeaways Important for IBPS Clerk Mains 2017 Exam- UNESCO- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. France's Audrey Azoulay- 11th DG of UNESCO, Headquarters- Paris, France. 3. Arunachal Pradesh Declared Open Defecation Free i. Arunachal Pradesh has been declared open defecation free ahead of the national deadline of October 2, 2019. The milestone was achieved after the state announced an incentive of Rs 8,000 in addition to the Rs 12,000-grant provided by the Centre for building toilets. ii. Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Haryana were declared open defecation free states in October 2017. -

List of Gram Panchayat Under Social Sector Ii of Local Audit Department

LIST OF GRAM PANCHAYAT UNDER SOCIAL SECTOR II OF LOCAL AUDIT DEPARTMENT Last SL. Audit DISTRICT BLOCK GP NO ed up to 2015- 1 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I BANCHUKAMARI 16 2015- 2 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I CHAKOWAKHETI 16 2015- 3 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I MATHURA 16 2015- 4 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I PARORPAR 16 2015- 5 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I PATLAKHAWA 16 2015- 6 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I PURBA KANTHALBARI 16 2015- 7 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I SHALKUMAR-I 16 2015- 8 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I SHALKUMAR-II 16 2015- 9 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I TAPSIKHATA 16 2015- 10 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I VIVEKANDA-I 16 2015- 11 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-I VIVEKANDA-II 16 2015- 12 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II BHATIBARI 16 2015- 13 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II CHAPORER PAR-I 16 2015- 14 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II CHAPORER PAR-II 16 2015- 15 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II KOHINOOR 16 2015- 16 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II MAHAKALGURI 16 2015- 17 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II MAJHERDABRI 16 2015- 18 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II PAROKATA 16 2015- 19 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II SHAMUKTALA 16 2015- 20 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II TATPARA-I 16 2015- 21 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II TATPARA-II 16 2015- 22 ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR-II TURTURI 16 2015- 23 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA DALGAON 16 2016- 24 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA DEOGAON 18 2015- 25 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA DHANIRAMPUR-I 16 2015- 26 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA DHANIRAMPUR-II 16 2015- 27 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA FALAKATA-I 16 2015- 28 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA FALAKATA-II 16 2016- 29 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA GUABARNAGAR 18 2015- 30 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA JATESWAR-I 16 2015- 31 ALIPURDUAR FALAKATA JATESWAR-II 16 2016- -

The People of India

LIBRARY ANNFX 2 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ^% Cornell University Library DS 421.R59 1915 The people of India 3 1924 024 114 773 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924024114773 THE PEOPLE OF INDIA =2!^.^ Z'^JiiS- ,SIH HERBERT ll(i 'E MISLEX, K= CoIoB a , ( THE PEOPLE OF INDIA w SIR HERBERT RISLEY, K.C.I.E., C.S.I. DIRECTOR OF ETHNOGRAPHY FOR INDIA, OFFICIER d'aCADEMIE, FRANCE, CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL SOCIETIES OF ROME AND BERLIN, AND OF THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND SECOND EDITION, EDITED BY W. CROOKE, B.A. LATE OF THE INDIAN CIVIL SERVICE "/« ^ood sooth, 7tiy masters, this is Ho door. Yet is it a little window, that looketh upon a great world" WITH 36 ILLUSTRATIONS AND AN ETHNOLOGICAL MAP OF INDIA UN31NDABL? Calcutta & Simla: THACKER, SPINK & CO. London: W, THACKER & CO., 2, Creed Lane, E.C. 191S PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, LONDON AND BECCLES. e 7/ /a£ gw TO SIR WILLIAM TURNER, K.C.B. CHIEF AMONG ENGLISH CRANIOLOGISTS THIS SLIGHT SKETCH OF A LARGE SUBJECT IS WITH HIS PERMISSION RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION In an article on "Magic and Religion" published in the Quarterly Review of last July, Mr. Edward Clodd complains that certain observations of mine on the subject of " the impersonal stage of religion " are hidden away under the " prosaic title " of the Report on the Census of India, 1901.