A Description of Non-Government Distance Education in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Following Schemes Are Used by Christian Heritage College (CHC) to Provide Adjustments to the Selection Ranks of Applicants T

The following schemes are used by Christian Heritage College (CHC) to provide adjustments to the selection ranks of applicants to CHC courses for admissions purposes: • CHC Partnership School Scheme; • CHC Community Engagement Scheme; and • Educational Access Scheme (EAS). Applicants must meet all other admission requirements for their preferred courses prior to the adjustments being applied. Only one scheme can be applied to an applicant’s selection rank. The requirements of the schemes, and the adjustments they provide, are explained below. Year 12 applicants can benefit from an adjustment of 2.00 selection ranks by completing Year 12 at a CHC Partner School (see Appendix 1). The CHC Community Engagement Scheme allows an adjustment of 2.00 selection ranks for applicants in CHC’s catchment area, according to their residential postcode (see Appendix 2). The Educational Access Scheme (EAS) allows an adjustment to be applied to the selection rank of applicants who have experienced difficult circumstances that have adversely impacted their studies. To be considered, applicants apply to QTAC for a confidential assessment of their circumstances. CRICOS Provider Name: Christian Heritage College CRICOS Provider No: 01016F The following are the schools to which the CHC Partnership School Scheme applies (as at July 2021): Greater Brisbane Area Regional Queensland Alta 1 College - Caboolture Bayside Christian College Hervey Bay (Urraween) Annandale Christian College Border Rivers Christian College (Goondiwindi) Arethusa College (Deception Bay Campus) -

What Parents Want an Independent Schools Queensland Survey

What Parents Want An Independent Schools Queensland Survey Key Findings FEBRUARY 2019 ABOUT INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS Queensland parents have been exercising their right to school choice for as long as some of the state’s oldest independent schools have been serving their local communities – more than 150 years. Independent schools are autonomous, not-for-profit institutions run and governed at the local level. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT SECTOR SNAPSHOT This survey was commissioned by Independent Schools Queensland STUDENTS: 121,000 (ISQ). 15% of all Queensland students For 51 years ISQ has been a 20% of all Queensland high school students united and powerful voice for 64% of all domestic boarding students Queensland’s independent schooling sector and a fierce SCHOOLS: 205 advocate for parental choice in 12% of all Queensland schools schooling. ISQ is a representative body for independent schools, not a SCHOOL TYPES regulator or governing authority. 149 Combined Dr Deidre Thian, Principal 26 Primary Consultant (Research) at ISQ is 26 Secondary acknowledged for her work in the 4 Special preparation of the 2018 report findings of the fourth What Parents SCHOOL GENDER Want – An Independent Schools 184 Co-educational Queensland Survey. 21 single-gender FAMILIES Independent schools serve families from all income levels SCHOOL IMAGES St John's Anglican College (cover) Mueller College (inside cover) Somerville House Matthew Flinders Anglican College The Cathedral School of St Anne & St James The Spot Academy School images are not necessarily aligned with the response quotes listed throughout this document. Quotes are a diverse selection from the 2018 survey. What Parents Want Survey 2018 What Parents Want – The survey delves into the decision-making processes of independent school parents An Independent Schools relating to the child who had most recently Queensland Survey is the commenced schooling at an independent longest running survey school. -

Annual Report 2016-2017

Non-State Schools Accreditation Board Non-State Schools Accreditation Board and Non-State Schools Eligibility for Government Funding Committee Level 8, Education House 30 Mary Street Brisbane, Queensland, Australia Tel +61 7 3513 6773 Postal address: PO Box 15347 City East, Queensland 4002 Email address: [email protected] Website address: www.nssab.qld.edu.au Further copies of this Annual Report may be obtained from the Board's website at www.nssab.qld.edu.au or from the Non-State Schools Accreditation Board Secretariat. ISSN 2206-9623 © Non-State Schools Accreditation Board 2017 22 August 2017 The Honourable Kate Jones MP Minister for Education Minister for Tourism, Major Events and the Commonwealth Games PO Box 15033 CITY EAST QLD 4002 Dear Minister I am pleased to submit for presentation to the Parliament the Annual Report 2016 – 2017 and financial statements for the Non-State Schools Accreditation Board. I certify that this Annual Report complies with: the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009, and the detailed requirements set out in the Annual report requirements for Queensland Government agencies. A checklist outlining the annual reporting requirements can be found at Appendix N of this Annual Report. Yours sincerely Emeritus Professor S Vianne (Vi) McLean AM Chairperson Non-State Schools Accreditation Board Contents About this report ..................................................................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2018-2019

Non-State Schools Accreditation Board Non-State Schools Accreditation Board Level 8, Education House 30 Mary Street Brisbane, Queensland, Australia Tel (07) 3513 6773 Postal address: PO Box 15347 City East, Queensland 4002 Email address: [email protected] Website address: www.nssab.qld.edu.au Further copies of this Annual Report may be obtained from the Board's website at www.nssab.qld.edu.au or from the Non-State Schools Accreditation Board Secretariat. ISSN 2206-9623 (online) ISSN 1447-5677 (print) © (Non-State Schools Accreditation Board) 2019 31 August 2019 The Honourable Grace Grace MP Minister for Education and Minister for Industrial Relations PO Box 15033 CITY EAST QLD 4002 Dear Minister I am pleased to submit for presentation to the Parliament the Annual Report 2018 – 2019 and financial statements for the Non-State Schools Accreditation Board. I certify that this annual report complies with: • the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009, and • the detailed requirements set out in the Annual report requirements for Queensland Government agencies. A checklist outlining the annual reporting requirements can be found at Appendix 16 of this annual report. Yours sincerely Lynne Foley OAM Chairperson Non-State Schools Accreditation Board Table of contents About this report ............................................................................................................................ 1 Scope ........................................................................................................................... -

2016 Annual Report Independent Schools Queensland Ltd ABN 88 662 995 577

2016 Annual Report Independent Schools Queensland Ltd ABN 88 662 995 577 John Paul College Front cover: Groves Christian College St Margaret’s Anglican Girls School Contents By the Numbers 2 Chair’s Report 4 Executive Director’s Report 8 ISQ Board and Committees 12 Independent Schools Advocacy, Research and Representation 14 Education Services 23 Queensland is the peak Governance and School Services 26 body representing Organisational Capability 29 Queensland’s independent Membership 30 schooling sector. Alliance Partners 34 Our 203 member schools ISQ Secretariat 36 are a vital part of the state’s education system. Together, these schools educate more than 120,000 students, or 15 percent of Queensland school enrolments. Independent Schools Queensland 2016 Annual Report 1 By the Numbers MEMBER SCHOOLS 15% of Queensland school enrolments 203 including nearly 20% of secondary enrolments 1 112 schools with approved Kindy 2 3 programs 78 schools with full fee paying overseas students 188 schools with Indigenous students 181 schools educated students with disability 35 schools offered boarding Cairns 114 schools with English as a Second Language or Dialect students 7 schools offered Townsville distance education Schools located 120,911 across 37 local government areas students enrolled Mackay 117,880 at 198 independent schools 3,031 at 5 Catholic schools 13 180 9 girls only schools offered boys only schools co-ed schooling schools Rockhampton 168 149 schools schools offered Bundaberg offered Prep primary & secondary Toowoomba Brisbane Warwick Data Source: 2016 Non-State School Census (State) February Collection 2 2016 Annual Report Independent Schools Queensland Flagship programs in 2016: Teaching and Learning Self-Improving Our Schools Governance Great Teachers in Academy Schools – Our Future Services Independent Schools 36% of member 45% of member Commissioned 39% of schools 97% of member schools participated in schools participated. -

Answers to Questions on Notice

QoN EW0112_10 Funding of Schools 2001 - 2010 ClientId Name of School Location State Postcode Sector year Capital Establishment IOSP Chaplaincy Drought Assistance Flagpole Country Areas Parliamentary Grants Grants Program Measure Funding Program and Civics Education Rebate 3 Corpus Christi School BELLERIVE TAS 7018 Catholic systemic 2002 $233,047 3 Corpus Christi School BELLERIVE TAS 7018 Catholic systemic 2006 $324,867 3 Corpus Christi School BELLERIVE TAS 7018 Catholic systemic 2007 $45,000 3 Corpus Christi School BELLERIVE TAS 7018 Catholic systemic 2008 $25,000 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2001 $182,266 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2002 $130,874 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2003 $41,858 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2006 $1,450 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2007 $22,470 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2002 $118,141 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2003 $123,842 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2004 $38,117 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2005 $5,000 $2,825 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2007 $32,500 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2009 $ 900.00 7 Holy Rosary School CLAREMONT TAS 7011 Catholic systemic 2005 $340,490 7 Holy Rosary School CLAREMONT TAS 7011 Catholic systemic 2007 $49,929 $1,190 9 Immaculate Heart of Mary School LENAH VALLEY TAS 7008 Catholic systemic 2006 $327,000 $37,500 9 Immaculate Heart of Mary -

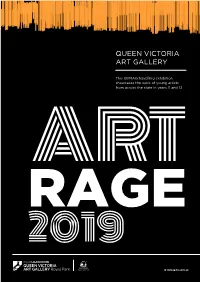

Artrage Cat2 A4.Pdf

ART RAGE 2019 QUEEN VICTORIA ART GALLERY This QVMAG travelling exhibition showcases the work of young artists from across the state in years 11 and 12 ART RAGE 2019 W qvmag.tas.gov.au ARTRAGE 2019 COLLECTION ArtRage is an annual initiative of the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery. This exhibition showcases the work of young artists from across Tasmania in years 11 and 12 who are studying Art Production or Art Studio Practice as part of their Tasmanian Certificate of Education. These artworks have been selected by the curator from works shortlisted by the art teachers of the various colleges. The works exhibited reflect the originality of the individual students and the creativity that is encouraged by these schools. ArtRage also highlights the range of media and techniques students use when telling us about the themes that have inspired them throughout the year. ArtRage continues to provide a wonderful opportunity for visitors to view the diverse and thought-provoking artworks by these talented and highly creative young artists. The Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery is proud to tour ArtRage across Tasmania, giving a wider audience the chance to engage with these dynamic works. The Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery would like to recognise ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS the enormous support and co-operation that ArtRage receives from the college art teachers of Tasmania. We would like to acknowledge the work of these dedicated art educators along with the talented students attending schools and colleges across Tasmania. qvmag_offical QVMAG -

Wordpowerwordpower STATE PRESIDENT’S PATCH —August 2016

Edition 77 Closing Date for next Newsletter is November 28th 2016 August 2016 WordPowerWordPower STATE PRESIDENT’S PATCH —August 2016 A very full 3 days in Melbourne at the annual Australian Rostrum Council (ARC) conference provided me with confidence that Rostrum has much to offer new and existing members across the 90 clubs in Australia. A reassuring trend is recognition in the corporate world that good communication skills are needed at all levels of business. Rostrum is well placed to provide the training, tutoring and practice that are essential elements for Inside this issue: success. However, these words are not enough. We must pay attention to our Wearing Effective Dress 3 “client expectations” if visitors are to return a second time, and then seek membership. Debate Adjudication 4– 6 Does your club have a rostered “host”, an information sheet for visitors and seek New Members 6,7 a follow-up contact? What is APSO? 8 In the past year, it is clear that a significant proportion of visitors come from RVOY NW 9 “googling” the web and other social media formats. Some are looking for a RVOY State Final 10,11 “quick fix”. Some are looking for a mix of development and social interaction. Rostrum can deliver both, even if the latter is easier for the Program Director. RVOY National 12,13 This year, NSW has built on Tasmania’s Accelerated Development program to Fmn Joe Bramble 14,15 deliver a 3 month program in 2016. NSW is trying a “half day public seminar” You’re the Voice 16 approach to get interested people together, and then offer a discount to those who wish to join a club. -

Tasmanian Primary All Schools XC 2019 12 Years Girls June 25, 2019

Tasmanian Primary All Schools XC_2019 12 Years Girls June 25, 2019 Place Name Team Bib Number Total Time 1 SOPHIE MARSHALL SCOTCH OAKBURN COLLEGE 268 11:00 2 AVERYL QUINN LAUNCESTON CHURCH GRAMMAR SCHOOL 674 11:24 3 JESSICA SMITH ST MARY'S COLLEGE 177 11:28 4 JEMIMA LENNON LENAH VALLEY PRIMARY SCHOOL 34 11:40 5 ABBEY BERLESE SACRED HEART SCHOOL (LAUNCESTON) 103 11:43 6 EMMA HENKEL ST MICHAEL'S COLLEGIATE SCHOOL 282 11:45 7 ARIANA REEVE HOWRAH PRIMARY SCHOOL 613 11:49 8 ELIANA DE WEYS SOUTHERN CHRISTIAN COLLEGE 1128 11:59 9 CHARLOTTE AUKSORIUS LAUDERDALE PRIMARY SCHOOL 31 12:10 10 ABBEY DEAN DEVONPORT PRIMARY SCHOOL 382 12:15 11 SAHARA REEVE HOWRAH PRIMARY SCHOOL 612 12:19 12 ISABELLA QUIN MOUNT CARMEL COLLEGE 420 12:24 13 BREEANNA HARPER SACRED HEART SCHOOL (LAUNCESTON) 104 12:30 14 LAUREN ANGILLEY OUR LADY OF LOURDES (DEVONPORT) 40 12:33 15 GEMMA MCCOY OUR LADY OF LOURDES (DEVONPORT) 39 12:39 16 AMALI WOOD PENGUIN DISTRICT SCHOOL 1226 12:47 17 JADE MCCOY OUR LADY OF LOURDES (DEVONPORT) 38 12:49 18 BRIDIE FINDLAY HAGLEY FARM PRIMARY SCHOOL 607 12:51 19 BREE STEELE ST MARY'S COLLEGE 176 12:52 20 INDIANNA RICHARDS Campania District 1221 12:54 21 CLARE GIBLIN WAIMEA HEIGHTS PRIMARY SCHOOL 955 12:54 22 MAGGIE STEELE FAHAN SCHOOL 10 12:55 23 ALLY-BREE D'SILVA CORPUS CHRISTI CATHOLIC SCHOOL 360 13:03 24 LUCY SMITH PERTH PRIMARY SCHOOL 257 13:07 25 IMOGEN LENNON LENAH VALLEY PRIMARY SCHOOL 35 13:11 26 SACHA WARE LANSDOWNE CRESCENT PRIMARY SCHOOL 654 13:15 27 ALLY WILSON PUNCHBOWL PRIMARY SCHOOL 62 13:16 28 URSULA NATION MOUNT CARMEL COLLEGE -

Answers to Questions on Notice

QoN E60_08 Funding of Schools 2001 - 2007 ClientId Name of School Location State Postcode Sector year Capital Establishment IOSP Chaplaincy Drought Assistance Flagpole Country Areas Parliamentary Grants Grants Program Measure Funding Program and Civics Education Rebate 3 Corpus Christi School BELLERIVE TAS 7018 Catholic systemic 2002 $233,047 3 Corpus Christi School BELLERIVE TAS 7018 Catholic systemic 2006 $324,867 3 Corpus Christi School BELLERIVE TAS 7018 Catholic systemic 2007 $45,000 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2001 $182,266 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2002 $130,874 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2003 $41,858 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2006 $1,450 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2007 $22,470 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2002 $118,141 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2003 $123,842 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2004 $38,117 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2005 $5,000 $2,825 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2007 $32,500 7 Holy Rosary School CLAREMONT TAS 7011 Catholic systemic 2005 $340,490 7 Holy Rosary School CLAREMONT TAS 7011 Catholic systemic 2007 $49,929 $1,190 9 Immaculate Heart of Mary School LENAH VALLEY TAS 7008 Catholic systemic 2006 $327,000 $37,500 10 John Calvin School LAUNCESTON TAS 7250 independent 2005 $41,083 10 John Calvin School LAUNCESTON TAS 7250 independent 2006 $44,917 $1,375 10 John Calvin School LAUNCESTON -

Queen Victoria Museum, Inveresk 19 December 2020 - 21 March 2021

a Queen victoria museum and art gallery travelling exhibition Showcasing Tasmania’s top year 11 & 12 artists for 2020 Queen Victoria Museum, Inveresk 19 December 2020 - 21 March 2021 www.qvmag.tas.gov.au Our Country • Our People • Our Stories ARTRAGE 2020 SELECTION ArtRage is an annual initiative of the Queen Victoria Museum by these schools. ArtRage also highlights the range of media and Art Gallery. This exhibition showcases the work of and techniques students use when telling us about the young artists from across Tasmania in years 11 and 12 who themes that have inspired them throughout the year. are studying or as part of their Tasmanian Certificate of ArtRage continues to provide a wonderful opportunity for Education. visitors to view the diverse and thought-provoking artworks These works have been selected by the curator from all by these talented and highly creative young artists. bodies of work across assessed in Art Production and Art The Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery is proud to tour Studio Practice. The works exhibited reflect the originality of ArtRage across Tasmania, giving a wider audience the chance the individual students and the creativity that is encouraged to engage with these dynamic works. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery recognises the enormous support and cooperation that ArtRage receives from the college art teachers of Tasmania. We acknowledge the work of these dedicated art educators along with the talented students attending schools and colleges across Tasmania. Q @qvmag_official -

Non-Government Reform Support Workplan Independent Schools

Non-Government Reform Support Workplan 2021 Independent Schools Tasmania Non – Government Reform Support Fund Independent Schools Tasmania – Workplan 2021 Summary of Workplan for 2021 IST provides state-wide support to all 32 Tasmanian independent schools. The 2021 NGRSF funding will provide, for all Independent Schools Tasmania (IST) member schools, an education support service as described in the Summary of Work Plan below and in the detailed plan that follows. In developing this plan, IST acknowledges the ongoing importance of research evidence that demonstrates the importance of contextual, school based professional learning (PL) and whole- school commitment to change and growth. The 2021 work plan will essentially follow the same format as past years, continuing on the work established thus far and as articulated in the strategic plan (2019-2022). As such, most details will flow on from current initiatives already in place, but updates have been provided, where applicable. Continuing projects commenced under the NGRSF priorities in 2018/19/20, and as part of the Bilateral reform agreements, will be ongoing in 2021. All of these projects extend beyond the normal service provision for schools, as summarised below: 1. Quality assurance, moderation and support for the continued improvement of the Nationally Consistent Collection of Data (NCCD) on School Students with Disability Project description and activities: • Develop teacher skills and judgement in discerning NCCD Levels of Adjustment through focussed PL and moderation opportunities. • Build teacher capacity to differentiate for quality teaching and learning for students at risk of educational disadvantage as a result of disability. Share of NGRSF = $58,333 2.