Disclosure and Conflict of Interest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cerebellum in Sagittal Plane-Anatomic-MR Correlation: 2

667 The Cerebellum in Sagittal Plane-Anatomic-MR Correlation: 2. The Cerebellar Hemispheres Gary A. Press 1 Thin (5-mm) sagittal high-field (1 .5-T) MR images of the cerebellar hemispheres James Murakami2 display (1) the superior, middle, and inferior cerebellar peduncles; (2) the primary white Eric Courchesne2 matter branches to the hemispheric lobules including the central, anterior, and posterior Dean P. Berthoty1 quadrangular, superior and inferior semilunar, gracile, biventer, tonsil, and flocculus; Marjorie Grafe3 and (3) several finer secondary white-matter branches to individual folia within the lobules. Surface features of the hemispheres including the deeper fissures (e.g., hori Clayton A. Wiley3 1 zontal, posterolateral, inferior posterior, and inferior anterior) and shallower sulci are John R. Hesselink best delineated on T1-weighted (short TRfshort TE) and T2-weighted (long TR/Iong TE) sequences, which provide greatest contrast between CSF and parenchyma. Correlation of MR studies of three brain specimens and 11 normal volunteers with microtome sections of the anatomic specimens provides criteria for identifying confidently these structures on routine clinical MR. MR should be useful in identifying, localizing, and quantifying cerebellar disease in patients with clinical deficits. The major anatomic structures of the cerebellar vermis are described in a companion article [1). This communication discusses the topographic relationships of the cerebellar hemispheres as seen in the sagittal plane and correlates microtome sections with MR images. Materials, Subjects, and Methods The preparation of the anatomic specimens, MR equipment, specimen and normal volunteer scanning protocols, methods of identifying specific anatomic structures, and system of This article appears in the JulyI August 1989 issue of AJNR and the October 1989 issue of anatomic nomenclature are described in our companion article [1]. -

Occurrence of Long-Term Depression in the Cerebellar Flocculus During Adaptation of Optokinetic Response Takuma Inoshita, Tomoo Hirano*

SHORT REPORT Occurrence of long-term depression in the cerebellar flocculus during adaptation of optokinetic response Takuma Inoshita, Tomoo Hirano* Department of Biophysics, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo-ku, Japan Abstract Long-term depression (LTD) at parallel fiber (PF) to Purkinje cell (PC) synapses has been considered as a main cellular mechanism for motor learning. However, the necessity of LTD for motor learning was challenged by demonstration of normal motor learning in the LTD-defective animals. Here, we addressed possible involvement of LTD in motor learning by examining whether LTD occurs during motor learning in the wild-type mice. As a model of motor learning, adaptation of optokinetic response (OKR) was used. OKR is a type of reflex eye movement to suppress blur of visual image during animal motion. OKR shows adaptive change during continuous optokinetic stimulation, which is regulated by the cerebellar flocculus. After OKR adaptation, amplitudes of quantal excitatory postsynaptic currents at PF-PC synapses were decreased, and induction of LTD was suppressed in the flocculus. These results suggest that LTD occurs at PF-PC synapses during OKR adaptation. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36209.001 Introduction The cerebellum plays a critical role in motor learning, and a type of synaptic plasticity long-term *For correspondence: depression (LTD) at parallel fiber (PF) to Purkinje cell (PC) synapses has been considered as a primary [email protected]. cellular mechanism for motor learning (Ito, 1989; Hirano, 2013). However, the hypothesis that LTD ac.jp is indispensable for motor learning was challenged by demonstration of normal motor learning in Competing interests: The rats in which LTD was suppressed pharmacologically or in the LTD-deficient transgenic mice authors declare that no (Welsh et al., 2005; Schonewille et al., 2011). -

…Going One Step Further

…going one step further C20 (1017868) 2 Latin A Encephalon Mesencephalon B Telencephalon 31 Lamina tecti B1 Lobus frontalis 32 Tegmentum mesencephali B2 Lobus temporalis 33 Crus cerebri C Diencephalon 34 Aqueductus mesencephali D Mesencephalon E Metencephalon Metencephalon E1 Cerebellum 35 Cerebellum F Myelencephalon a Vermis G Circulus arteriosus cerebri (Willisii) b Tonsilla c Flocculus Telencephalon d Arbor vitae 1 Lobus frontalis e Ventriculus quartus 2 Lobus parietalis 36 Pons 3 Lobus occipitalis f Pedunculus cerebellaris superior 4 Lobus temporalis g Pedunculus cerebellaris medius 5 Sulcus centralis h Pedunculus cerebellaris inferior 6 Gyrus precentralis 7 Gyrus postcentralis Myelencephalon 8 Bulbus olfactorius 37 Medulla oblongata 9 Commissura anterior 38 Oliva 10 Corpus callosum 39 Pyramis a Genu 40 N. cervicalis I. (C1) b Truncus ® c Splenium Nervi craniales d Rostrum I N. olfactorius 11 Septum pellucidum II N. opticus 12 Fornix III N. oculomotorius 13 Commissura posterior IV N. trochlearis 14 Insula V N. trigeminus 15 Capsula interna VI N. abducens 16 Ventriculus lateralis VII N. facialis e Cornu frontale VIII N. vestibulocochlearis f Pars centralis IX N. glossopharyngeus g Cornu occipitale X N. vagus h Cornu temporale XI N. accessorius 17 V. thalamostriata XII N. hypoglossus 18 Hippocampus Circulus arteriosus cerebri (Willisii) Diencephalon 1 A. cerebri anterior 19 Thalamus 2 A. communicans anterior 20 Sulcus hypothalamicus 3 A. carotis interna 21 Hypothalamus 4 A. cerebri media 22 Adhesio interthalamica 5 A. communicans posterior 23 Glandula pinealis 6 A. cerebri posterior 24 Corpus mammillare sinistrum 7 A. superior cerebelli 25 Hypophysis 8 A. basilaris 26 Ventriculus tertius 9 Aa. pontis 10 A. -

Cerebellum and Activation of the Cerebellum IO ST During Nonmotor Tasks

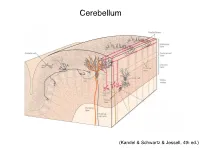

Cerebellum (Kandel & Schwartz & Jessell, 4th ed.) Granule186 cells are irreducibly smallChapter (6-8 7 μm) stellate cell basket cell outer synaptic layer PC rs cap PC layer grc Go inner 6 μm synaptic layer Figure 7.15 Largest cerebellar neuron occupies more than a 1,000-fold greater volume than smallest neuron. Thin section (~1 μ m) through monkey cerebellar cortex. Purkinje cell body (PC) and nucleus are far larger than those of granule cell (grc). The latter cluster to leave space for mossy fiber terminals to form glomeruli with grc dendritic claws and space for Golgi cells (Go). Note rich network of capillaries (cap). Fine, scat- tered dots are mitochondria. Courtesy of E. Mugnaini. brain ’ s most numerous neuron, this small cost grows large (see also chapter 13). Much of the inner synaptic layer is occupied by the large axon terminals of mossy fibers (figures 7.1 and 7.16). A terminal interlaces with multiple (~15) dendritic claws, each from a different but neighboring granule cell, and forms a complex knot (glomerulus ), nearly as large as a granule cell body (figures 7.1 and 7.16). The mossy fiber axon fires at an unusually high mean rate (up to 200 Hz) and is therefore among the brain’ s thickest (figure 4.6). To match the axon’ s high rate, a terminal expresses 150 active zones, 10 per postsynaptic granule cell (figure 7.16). These sites are capable of driving … and most expensive. 190 Chapter 7 10 4 8 3 9 19 10 10 × 6 × 2 2 4 ATP/s/cell ATP/s/cell ATP/s/m 1 2 0 0 astrocyte astrocyte Golgi cell Golgi cell basket cell basket cell stellate cell stellate cell granule cell granule cell mossy fiber mossy fiber Purkinje cell Purkinje Purkinje cell Purkinje Bergman glia Bergman glia climbing fiber climbing fiber Figure 7.18 Energy costs by cell type. -

Neuroimaging Evidence Implicating Cerebellum in Support of Sensory Cognitive Processes Associated with Thirst

Neuroimaging evidence implicating cerebellum in support of sensory͞cognitive processes associated with thirst Lawrence M. Parsons*†, Derek Denton‡, Gary Egan‡, Michael McKinley‡, Robert Shade‡, Jack Lancaster*, and Peter T. Fox* *Research Imaging Center, Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78284; ‡Howard Florey Institute of Experimental Physiology and Medicine, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; and §Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research, P.O. Box 760549, San Antonio, TX 78245-0549 Contributed by Derek A. Denton, December 13, 1999 Recent studies implicate the cerebellum, long considered strictly a and tactile discrimination, kinesthetic sensation, and working motor control structure, in cognitive, sensory, and affective phe- memory, among other processes (6–12). It has been proposed nomenon. The cerebellum, a phylogenetically ancient structure, that the lateral cerebellum may be activated during several has reciprocal ancient connections to the hypothalamus, a struc- motor, perceptual, and cognitive processes specifically because ture important in vegetative functions. The present study investi- of the requirement to monitor and adjust the acquisition of gated whether the cerebellum was involved in vegetative func- sensory data (2, 13). Furthermore, there are reports suggesting tions and the primal emotions engendered by them. Using positron the involvement of posterior vermal cerebellum in affect (14, 15). emission tomography, we examined the effects on the cerebellum The findings implicating the cerebellum in sensory processing of the rise of plasma sodium concentration and the emergence of and emotional states make it of great interest to examine thirst in 10 healthy adults. The correlation of regional cerebral whether the cerebellum has a role in basic vegetative functions blood flow with subjects’ ratings of thirst showed major activation and the primal emotions thus generated, particularly given the in the vermal central lobule. -

On the Function of the Floccular Complex of the Vertebrate Cerebellum: Implications in Paleoneuroanatomy

On the function of the floccular complex of the vertebrate cerebellum: implications in paleoneuroanatomy Sérgio Filipe Ferreira Cardoso Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Paleontologia Orientador: Doutor Rui Alexandre Ferreira Castanhinha Co-orientadores: Doutor Ricardo Miguel Nóbrega Araújo Prof. Doutor Miguel Telles Antunes On the function of the floccular complex of the vertebrate cerebellum: implications in paleoneuroanatomy Sérgio Filipe Ferreira Cardoso Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Paleontologia Orientador: Doutor Rui Alexandre Ferreira Castanhinha Co-orientadores: Doutor Ricardo Miguel Nóbrega Araújo Prof. Doutor Miguel Telles Antunes Successfully defended on 18th November 2015 at FCT-UNL Campus, Portugal, before a juri presided over by: Doutor Paulo Alexandre Rodrigues Roque Legoinha and consisting of: Doutor Gabriel José Gonçalves Martins Doutor Rui Alexandre Ferreira Castanhinha I II Direitos de autor - Copyright Os direitos de autor deste documento pertencem a Sérgio Filipe Ferreira Cardoso, à FCT/UNL, à UNL e à UÉ. A Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, a Universidade Nova de Lisboa e a Universidade de Évora têm o direito, perpétuo e sem limites geográficos, de arquivar e publicar esta dissertação através de exemplares impressos reproduzidos em papel ou de forma digital, ou por qualquer outro meio conhecido ou que venha a ser inventado, e de a divulgar através de repositórios científicos e de admitir a sua cópia e distribuição com objectivos educacionais ou de investigação, não comerciais, desde que seja dado crédito ao autor e editor. Two peer-reviewed abstracts, resulting from this study, were accepted for oral communications (Appendix II). Ferreira-Cardoso, S., Araújo, R., Castanhinha, R., Walsh, S., Martins, R.M.S., Martins, G.G. -

The Cerebellum in Eye Movement Control

Eye (2015) 29, 191–195 & 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-222X/15 www.nature.com/eye CAMBRIDGE OPHTHALMOLOGICAL SYMPOSIUM The cerebellum in VR Patel1 and DS Zee2 eye movement control: nystagmus, coordinate frames and disconjugacy This article has been corrected since Advance Online Publication and an erratum is also printed in this issue Abstract cerebellum in binocular control—both to create disconjugacy when it is necessary, and to In this review we discuss several aspects of prevent ocular misalignment when it is eye movement control in which the unnecessary and disruptive. We will also touch cerebellum is thought to have a key role, but on the implications of evolving into frontal-eyed have been relatively ignored. We will focus creatures, with the competing demands on the mechanisms underlying certain forms of binocular, foveal vs retinal, full-field of cerebellar nystagmus, as well as the stabilization of images. Furthermore, we contributions of the cerebellum to binocular suggest that the phylogenetically old vestibular alignment in healthy and diseased states. anlage persists in a rudimentary form within A contemporary review of our understanding our human brains and its vestiges can be provides a basis for directions of further 1Associate Professor of uncovered in neurological disease.1–4 These inquiry to address some of the uncertainties Ophthalmology, USC Eye issues bear on interpretation of pathological regarding the contributions of the cerebellum Institute, Keck School of nystagmus, which depends on the coordinate Medicine, University of to ocular motor control. system in which the nystagmus is couched Southern California, Eye (2015) 29, 191–195; doi:10.1038/eye.2014.271; Los Angeles, CA, USA (foveal: eye frame vs full-field retina: head published online 14 November 2014 frame), and also on the types of ocular 2Professor of Neurology, misalignment seen in cerebellar patients. -

Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 6 with Positional Vertigo and Acetazolamide Responsive Episodic Ataxia

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.65.4.565 on 1 October 1998. Downloaded from J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;65:565–568 565 SHORT REPORT Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 with positional vertigo and acetazolamide responsive episodic ataxia Joanna C Jen, Qing Yue, Juliana Karrim, Stanley F Nelson, Robert W Baloh Abstract tions in other parts of CACNA1A. SCA6 has The SCA6 mutation, a small expansion of clinical features that overlap with those of a CAG repeat in a calcium channel gene EA-2. CACNA1A, was identified in three pedi- grees. Point mutations in other parts of Case reports the gene CACNA1A were excluded and The study was approved by our institutional new clinical features of SCA6 reported— review board and informed consent was namely, central positional nystagmus and obtained from all subjects. The pedigrees are episodic ataxia responsive to acetazola- shown in the figure. mide. The three allelic disorders, episodic ataxia type 2, familial hemiplegic mi- PEDIGREE 1 graine, and SCA6, have overlapping clini- This family was previously reported as an cal features. atypical EA-2 linked to chromosome 19p (J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;65:565–568) (family 4).5 The type of mutation was un- known. The proband began having episodes of Keywords: SCA6; spinocerebellar ataxia; hereditary dizziness and ataxia at the age of 42. She also ataxia; calcium channel noted positional vertigo so that she slept propped up with pillows. About a year later, she noticed mild interictal imbalance. Initial exam- Episodic ataxia type 2 (EA-2) is an autosomal ination disclosed a central type of positional dominant disorder characterised by episodes of nystagmus (conjugate downbeat nystagmus ataxia lasting hours to days with interictal nys- that did not fatigue with repeated positioning). -

Zonal Organization of the Flocculovestibular Nucleus Projection in the Rabbit: a Combined Axonal Tracing and Acetylcholinesterase Histochemicalstudy

THE JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE NEUROLOGY 354k51-71 (1995) Zonal Organization of the Flocculovestibular Nucleus Projection in the Rabbit: A Combined Axonal Tracing and Acetylcholinesterase HistochemicalStudy J. TAN, A.H. EPEMA, AND J. VOOGD Department of Anatomy, Erasmus University Rotterdam, 3000 DR Rotterdam, The Netherlands (J.T., J.V.) and Department of Anesthesiology, Academic Hospital, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands (A.H.E.) ABSTRACT With the use of retrograde transport of horseradish peroxidase we confirmed the observation of Yamamoto and Shimoyama ([ 19771 Neurosci Lett. 5279-283) that Purkinje cells of the rabbit flocculus projecting to the medial vestibular nucleus are located in two discrete zones, FZIl and FZlv, that alternate with two other Purkinje cell zones, FZI and FZIII, projecting to the superior vestibular nucleus. The retrogradely labeled axons of these Purkinje cells collect in four bundles that occupy the corresponding floccular white matter compart- ments, FC1-4,that can be delineated with acetylcholinesterase histochemistry (Tan et al. [ 1995al J. Comp. Neurol., this issue). Anterograde tracing from small injections of wheat germ agglutin-hoseradish peroxidase in single Purkinje cell zones of the flocculus showed that Purkinje cell axons of FZrr travel in FC2to terminate in the medial vestibular nucleus. Purkinje cell axons from FZI and FZIII occupy the FCI and FC3 compartments, respectively, and terminate in the superior vestibular nucleus. Purkinje cell axons from all three compartments pass through the floccular peduncle and dorsal group y. In addition, some fibers from FZI and FZIJ,but not from FZIII, arch through the cerebellar nuclei to join the floccular peduncle more medially. -

Microvascular Anatomy of the Cerebellar Parafloccular Perforating Space

LABORATORY INVESTIGATION J Neurosurg 124:440–449, 2016 Microvascular anatomy of the cerebellar parafloccular perforating space Pablo Sosa, MD,1 Manuel Dujovny, MD,2 Ibe Onyekachi, BS,2 Noressia Sockwell, BS,2 Fabián Cremaschi, MD,1 and Luis E. Savastano, MD3 1Department of Neuroscience, Clinical and Surgical Neurology, School of Medicine, National University of Cuyo, Mendoza, Argentina; 2Departments of Neurosurgery and Electrical Engineering, Wayne State University, Detroit; and 3Department of Neurosurgery, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan OBJECTIVE The cerebellopontine angle is a common site for tumor growth and vascular pathologies requiring surgical manipulations that jeopardize cranial nerve integrity and cerebellar and brainstem perfusion. To date, a detailed study of vessels perforating the cisternal surface of the middle cerebellar peduncle—namely, the paraflocculus or parafloccular perforating space—has yet to be published. In this report, the perforating vessels of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) in the parafloccular space, or on the cisternal surface of the middle cerebellar peduncle, are described to eluci- date their relevance pertaining to microsurgery and the different pathologies that occur at the cerebellopontine angle. METHODS Fourteen cadaveric cerebellopontine cisterns (CPCs) were studied. Anatomical dissections and analysis of the perforating arteries of the AICA and posterior inferior cerebellar artery at the parafloccular space were recorded using direct visualization by surgical microscope, optical histology, and scanning electron microscope. A comprehensive review of the English-language and Spanish-language literature was also performed, and findings related to anatomy, histology, physiology, neurology, neuroradiology, microsurgery, and endovascular surgery pertaining to the cerebellar flocculus or parafloccular spaces are summarized. RESULTS A total of 298 perforating arteries were found in the dissected specimens, with a minimum of 15 to a maxi- mum of 26 vessels per parafloccular perforating space. -

MRI Analysis of Cerebellar and Vestibular Developmental Phenotypes in Gbx2 Conditional Knockout Mice

Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 70:1707–1717 (2013) MRI Analysis of Cerebellar and Vestibular Developmental Phenotypes in Gbx2 Conditional Knockout Mice Kamila U. Szulc,1,2 Brian J. Nieman,3 Edward J. Houston,1 Benjamin B. Bartelle,1,4 Jason P. Lerch,3 Alexandra L. Joyner,5 and Daniel H. Turnbull1,2,4,6,7* Purpose: Our aim in this study was to apply three-dimensional mouse models of neurodevelopmental diseases. Magn Reson MRI methods to analyze early postnatal morphological pheno- Med 70:1707–1717, 2013. VC 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. types in a Gbx2 conditional knockout (Gbx2-CKO) mouse that has variable midline deletions in the central cerebellum, remi- Key words: brain development; cerebellum; gastrulation brain niscent of many human cerebellar hypoplasia syndromes. homeobox 2 gene (Gbx2); manganese-enhanced MRI Methods: In vivo three-dimensional manganese-enhanced (MEMRI); mid-hindbrain; vestibulo-cochlear organ MRI at 100-mm isotropic resolution was used to visualize mouse brains between postnatal days 3 and 11, when cere- bellum morphology undergoes dramatic changes. Deforma- Advances in the field of mouse genetics have been criti- tion-based morphometry and volumetric analysis of cal in elucidating the roles of different genes in mamma- manganese-enhanced MRI images were used to, respectively, lian brain development and neurodevelopmental dis- detect and quantify morphological phenotypes in Gbx2-CKO eases (1–3). Specifically, genetic defects are commonly mice. Ex vivo micro-MRI was performed after perfusion-fixa- associated with congenital brain malformations, which tion with supplemented gadolinium for higher resolution (50- can be mimicked in mutant mice to better understand mm) analysis. -

Cerebellar Development and Neurogenesis in Zebrafish

Cerebellar Development and Neurogenesis in Zebrafish Jan Kaslin1* and Michael Brand2* 1) Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute, Monash University, Innovation Walk 15, Clayton, Victoria, 3800, Melbourne, Australia 2) Biotechnology Center and Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden, Dresden University of Technology, Tatzberg 47, 01307, Germany *Corresponding authors: [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: zebrafish, teleost, fish, adult neurogenesis, mutant, screening, eurydendroid cell, genetic model, cerebellar development, morphogenesis, mid-hindbrain-boundary, isthmic organizer, in vivo imaging 1. Introduction Cerebellar organization and function have been studied in numerous species of fish. Fish models such as goldfish and weakly electric fish have led to important findings about the cerebellar architecture, cerebellar circuit physiology and brain evolution. owever,H most of the studied fish models are not well suited for developmental and genetic studies of the cerebellum. The rapid transparent ex utero development in zebrafish allows direct access and precise visualization of all the major events in cerebellar development. The superficial position of the cerebellarprimordium and cerebellum further facilitatesin vivo imaging of cerebellar structures and developmental events at single cell resolution. Furthermore, zebrafish is amenable to high-throughput screening techniques and forward genetics because of its fecundity and easy keeping. Forward genetics screens in zebrafish have resulted in several isolated cerebellar mutants and substantially contributed to the understanding of the genetic networks involved in hindbrain development(Bae et al. 2009;Brand et al. 1996). Recent developments in genetic tools, including the use of site specific recombinases, efficient transgenesis, inducible gene expression systems, and the targeted genome lesioning technologies TALEN and Cas9/CRISPR has opened up new avenues to manipulate and edit the genome of zebrafish (Hans et al.