The Cerebellum in Eye Movement Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cerebellum in Sagittal Plane-Anatomic-MR Correlation: 2

667 The Cerebellum in Sagittal Plane-Anatomic-MR Correlation: 2. The Cerebellar Hemispheres Gary A. Press 1 Thin (5-mm) sagittal high-field (1 .5-T) MR images of the cerebellar hemispheres James Murakami2 display (1) the superior, middle, and inferior cerebellar peduncles; (2) the primary white Eric Courchesne2 matter branches to the hemispheric lobules including the central, anterior, and posterior Dean P. Berthoty1 quadrangular, superior and inferior semilunar, gracile, biventer, tonsil, and flocculus; Marjorie Grafe3 and (3) several finer secondary white-matter branches to individual folia within the lobules. Surface features of the hemispheres including the deeper fissures (e.g., hori Clayton A. Wiley3 1 zontal, posterolateral, inferior posterior, and inferior anterior) and shallower sulci are John R. Hesselink best delineated on T1-weighted (short TRfshort TE) and T2-weighted (long TR/Iong TE) sequences, which provide greatest contrast between CSF and parenchyma. Correlation of MR studies of three brain specimens and 11 normal volunteers with microtome sections of the anatomic specimens provides criteria for identifying confidently these structures on routine clinical MR. MR should be useful in identifying, localizing, and quantifying cerebellar disease in patients with clinical deficits. The major anatomic structures of the cerebellar vermis are described in a companion article [1). This communication discusses the topographic relationships of the cerebellar hemispheres as seen in the sagittal plane and correlates microtome sections with MR images. Materials, Subjects, and Methods The preparation of the anatomic specimens, MR equipment, specimen and normal volunteer scanning protocols, methods of identifying specific anatomic structures, and system of This article appears in the JulyI August 1989 issue of AJNR and the October 1989 issue of anatomic nomenclature are described in our companion article [1]. -

Eye-Movement Studies of Visual Face Perception

Eye-movement studies of visual face perception Joseph Arizpe A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University College London Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience University College London 2015 1 Declaration I, Joseph Arizpe, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis investigates factors influencing eye-movement patterns during face perception, the relationship of eye-movement patterns to facial recognition performance, and methodological considerations impacting the detection of differences in eye-movement patterns. In particular, in the first study (chapter 2), in which the basis of the other-race effect was investigated, differences in eye- movement patterns during recognition of own- versus other-race (African, Chinese) faces were found for Caucasian participants. However, these eye- movement differences were subtle and analysis-dependent, indicating that the discrepancy in prior reports regarding the presence or absence of such differences are due to variability in statistical sensitivity of analysis methods across studies. The second and third studies (chapters 3 and 4) characterized visuomotor factors, specifically pre-stimulus start position and distance, which strongly influence subsequent eye-movement patterns during face perception. An overall bias in fixation patterns to the opposite side of the face induced by start position and an increasing undershoot of the first ordinal fixation with increasing start distance were found. These visuomotor influences were not specific to faces and did not depend on the predictability of the location of the upcoming stimulus. -

Eye Fields in the Frontal Lobes of Primates

Brain Research Reviews 32Ž. 2000 413±448 www.elsevier.comrlocaterbres Full-length review Eye fields in the frontal lobes of primates Edward J. Tehovnik ), Marc A. Sommer, I-Han Chou, Warren M. Slocum, Peter H. Schiller Department of Brain and CognitiÕe Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, E25-634, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA Accepted 19 October 1999 Abstract Two eye fields have been identified in the frontal lobes of primates: one is situated dorsomedially within the frontal cortex and will be referred to as the eye field within the dorsomedial frontal cortexŽ. DMFC ; the other resides dorsolaterally within the frontal cortex and is commonly referred to as the frontal eye fieldŽ. FEF . This review documents the similarities and differences between these eye fields. Although the DMFC and FEF are both active during the execution of saccadic and smooth pursuit eye movements, the FEF is more dedicated to these functions. Lesions of DMFC minimally affect the production of most types of saccadic eye movements and have no effect on the execution of smooth pursuit eye movements. In contrast, lesions of the FEF produce deficits in generating saccades to briefly presented targets, in the production of saccades to two or more sequentially presented targets, in the selection of simultaneously presented targets, and in the execution of smooth pursuit eye movements. For the most part, these deficits are prevalent in both monkeys and humans. Single-unit recording experiments have shown that the DMFC contains neurons that mediate both limb and eye movements, whereas the FEF seems to be involved in the execution of eye movements only. -

Occurrence of Long-Term Depression in the Cerebellar Flocculus During Adaptation of Optokinetic Response Takuma Inoshita, Tomoo Hirano*

SHORT REPORT Occurrence of long-term depression in the cerebellar flocculus during adaptation of optokinetic response Takuma Inoshita, Tomoo Hirano* Department of Biophysics, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo-ku, Japan Abstract Long-term depression (LTD) at parallel fiber (PF) to Purkinje cell (PC) synapses has been considered as a main cellular mechanism for motor learning. However, the necessity of LTD for motor learning was challenged by demonstration of normal motor learning in the LTD-defective animals. Here, we addressed possible involvement of LTD in motor learning by examining whether LTD occurs during motor learning in the wild-type mice. As a model of motor learning, adaptation of optokinetic response (OKR) was used. OKR is a type of reflex eye movement to suppress blur of visual image during animal motion. OKR shows adaptive change during continuous optokinetic stimulation, which is regulated by the cerebellar flocculus. After OKR adaptation, amplitudes of quantal excitatory postsynaptic currents at PF-PC synapses were decreased, and induction of LTD was suppressed in the flocculus. These results suggest that LTD occurs at PF-PC synapses during OKR adaptation. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36209.001 Introduction The cerebellum plays a critical role in motor learning, and a type of synaptic plasticity long-term *For correspondence: depression (LTD) at parallel fiber (PF) to Purkinje cell (PC) synapses has been considered as a primary [email protected]. cellular mechanism for motor learning (Ito, 1989; Hirano, 2013). However, the hypothesis that LTD ac.jp is indispensable for motor learning was challenged by demonstration of normal motor learning in Competing interests: The rats in which LTD was suppressed pharmacologically or in the LTD-deficient transgenic mice authors declare that no (Welsh et al., 2005; Schonewille et al., 2011). -

Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science

APRIL 1978 Vol. 17/4 Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science A Journal of Clinical and Basic Research Articles Training of voluntary torsion Richard Balliet and Ken Nakayama By means of a visual feedback technique, human subjects were trained to make large conjugate cyclorotary eye movements at will. The range of movement increased with training at a rate of approximately 0.8° per hour of practice, reaching 30° at the end of training. Photographs recorded the ability to make voluntary cyclofixations at any amplitude within the subject's range. Cyclotorsional pursuit was also trained, with ability increasing with greater amounts of visual feedback. In addition, torsional saccadic tracking was trained, showing a magnitude vs. peak velocity relationship similar to that seen for normal saccades. Control experiments indi- cate that all of these movements were voluntary, with no significant visual induction. With extended practice, large torsional movements could be made without any visual stimulation. The emergence of voluntary torsion through training demonstrates that the oculomotor system has more plasticity than has generally been assumed, reopening the issue as to whether other movements could also be trained to alleviate the symptoms of strabismus. Key words: eye movements, torsion, saccades, slow pursuit, fixation, orthoptics, oculomotor plasticity c' yclorotations are defined as rotations the eye can undergo a cyclorotation as it about the visual axis of the eye. These rota- moves from one tertiary position of gaze to tions are considered to be reflexive, with no another, but the amount of this cyclorotation indication of voluntary control. For example, is fixed, being dictated by Listings law.11 In addition, involuntary cyclovergence has been 1 From the Smith-Kettlewell Institute of Visual Science, reported to occur during convergence, and Department of Visual Sciences, University of the reflexive cycloversions have been demon- Pacific, San Francisco, Calif. -

The Effect of Eye Movements and Blinks on Afterimage Appearance and Duration

Journal of Vision (2015) 15(3):20, 1–15 http://www.journalofvision.org/content/15/3/20 1 The effect of eye movements and blinks on afterimage appearance and duration School of Psychology, Cardiff University, # Georgina Powell Cardiff, Wales, UK $ School of Psychology, Cardiff University, # Petroc Sumner Cardiff, Wales, UK $ Lyon Neuroscience Research Center, # Aline Bompas Centre Hospitalier Vinatier, Bron, Cedex, France $ The question of whether eye movements influence argued that afterimage signals are inherently ambigu- afterimage perception has been asked since the 18th ous, and this could explain why their visibility is century, and yet there is surprisingly little consensus on influenced by cues, such as surrounding luminance how robust these effects are and why they occur. The edges, more than are real stimuli (Powell, Bompas, & number of historical theories aiming to explain the Sumner, 2012). Helmholtz (1962) identified another cue effects are more numerous than clear experimental that is important to take into account when conducting demonstrations of such effects. We provide a clearer afterimage experiments: characterization of when eye movements and blinks do or do not affect afterimages with the aim to distinguish For obtaining really beautiful positive after- between historical theories and integrate them with a images, the following additional rules should be modern understanding of perception. We found neither saccades nor pursuit reduced strong afterimage observed. Both before and after they are devel- duration, and blinks actually increased afterimage oped, any movement of the eye or any sudden duration when tested in the light. However, for weak movement of the body must be carefully avoided, afterimages, we found saccades reduced duration, and because under such circumstances they invariably blinks and pursuit eye movements did not. -

Cine Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Eye Movements

CINE MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING OF EYE MOVEMENTS C. c. BAILEY\ J. KABALA2, R. LAITT2, M. WESTON2, P. GODDARD2, H. B. HOHl, M. J. POTTSl and R. A. HARRADl Bristol SUMMARY Images were obtained using the FISP 2D sequence (fast Cine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a technique in imaging with a steady state progression). The patient was which multiple sequential static orbital MRI films are positioned within the head coil in the magnet. A strip of taken while the patient fixates a series of targets across paper with six separate marks set 30° apart was suspended the visual field. These are then sequenced to give a in front of the patient and aligned either transversely or graphic animation to the eyes. The excellent soft tissue sagittally depending on the eye movement of interest. The differentiationofMRI, combined with the dynamic imag patient was asked to look sequentially at each mark on the ing, allows rapid visualisation, and functional assessment paper, and a scan was performed in each position. Each of the extraocular muscles. Good assessment of contrac image took 15 seconds to acquire. After the patient had tility can be obtained, but the technique does not allow fixated all six points the procedure was repeated in reverse study of saccadic or pursuit eye movements. We have order. The images generated were then displayed as a used this technique in 36 patients with a range of ocular continuous video loop. The total time required to generate motility disorders, including thyroid-related ophthalmo a video loop for each patient was only 6 minutes. -

…Going One Step Further

…going one step further C20 (1017868) 2 Latin A Encephalon Mesencephalon B Telencephalon 31 Lamina tecti B1 Lobus frontalis 32 Tegmentum mesencephali B2 Lobus temporalis 33 Crus cerebri C Diencephalon 34 Aqueductus mesencephali D Mesencephalon E Metencephalon Metencephalon E1 Cerebellum 35 Cerebellum F Myelencephalon a Vermis G Circulus arteriosus cerebri (Willisii) b Tonsilla c Flocculus Telencephalon d Arbor vitae 1 Lobus frontalis e Ventriculus quartus 2 Lobus parietalis 36 Pons 3 Lobus occipitalis f Pedunculus cerebellaris superior 4 Lobus temporalis g Pedunculus cerebellaris medius 5 Sulcus centralis h Pedunculus cerebellaris inferior 6 Gyrus precentralis 7 Gyrus postcentralis Myelencephalon 8 Bulbus olfactorius 37 Medulla oblongata 9 Commissura anterior 38 Oliva 10 Corpus callosum 39 Pyramis a Genu 40 N. cervicalis I. (C1) b Truncus ® c Splenium Nervi craniales d Rostrum I N. olfactorius 11 Septum pellucidum II N. opticus 12 Fornix III N. oculomotorius 13 Commissura posterior IV N. trochlearis 14 Insula V N. trigeminus 15 Capsula interna VI N. abducens 16 Ventriculus lateralis VII N. facialis e Cornu frontale VIII N. vestibulocochlearis f Pars centralis IX N. glossopharyngeus g Cornu occipitale X N. vagus h Cornu temporale XI N. accessorius 17 V. thalamostriata XII N. hypoglossus 18 Hippocampus Circulus arteriosus cerebri (Willisii) Diencephalon 1 A. cerebri anterior 19 Thalamus 2 A. communicans anterior 20 Sulcus hypothalamicus 3 A. carotis interna 21 Hypothalamus 4 A. cerebri media 22 Adhesio interthalamica 5 A. communicans posterior 23 Glandula pinealis 6 A. cerebri posterior 24 Corpus mammillare sinistrum 7 A. superior cerebelli 25 Hypophysis 8 A. basilaris 26 Ventriculus tertius 9 Aa. pontis 10 A. -

Pseudogaze in Afterimages

Journal of Vision (2016) 16(5):6, 1–10 1 Where are you looking? Pseudogaze in afterimages Caltech Brain Imaging Center, Division of Humanities and Social Sciences, California Institute of Technology, # Daw-An Wu Pasadena, CA, USA $ Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA Laboratoire Psychologie de la Perception, Universite´ # Patrick Cavanagh Paris Descartes, Paris, France $ How do we know where we are looking? A frequent gaze seems exceptionally well defined and we seldom assumption is that the subjective experience of our feel that we don’t know where we are looking within a direction of gaze is assigned to the location in the world visual scene. The conceptual equivalence of mental and that falls on our fovea. However, we find that observers physical gaze is ingrained to the point that the two can shift their subjective direction of gaze among concepts share almost all their terminology, even in different nonfoveal points in an afterimage. Observers scientific and technical usage. Terms such as ‘‘gaze,’’ were asked to look directly at different corners of a ‘‘look at,’’ ‘‘fixate,’’ etc. do not distinguish between the diamond-shaped afterimage. When the requested corner subjective sense of visual targeting and the physical was 3.58 in the periphery, the observer often reported pointing of the eyes at something. that the image moved away in the direction of the Whereas a large body of work exists regarding the attempted gaze shift. However, when the corner was at perceived direction of visual targets in egocentric space 1.758 eccentricity, most reported successfully fixating at the point. -

Types of Eye Movements

Types of Eye Movements The information given here is deliberately non-technical and is based for a general Background audience. With apologies to eye movement research colleagues for liberties taken in Objective simplification. Challenges Visual Search & Paintings In our everyday lives we regularly make various types of eye movements, usually without The Exhibit being aware of them. Such movements occur as a result of the activity of the three pairs of Updates antagonistic muscles that support each eye. There are several ways to record eye Press Reports movements and more information can be found here. Links FAQ In looking at paintings, or other two-dimensional scenes, only saccadic eye movements and their associated fixations, in the main, are of research interest. Miniature eye People movements also occur, and these overlay the fixations causing many small movements which, to a large extent, can be regarded as ‘system noise’ (unless the researcher is Home specifically interested in these movements). Main types of eye movements:- [this list of links all link to subsequent sections on this page] Saccade Miniature Pursuit Smooth Compensatory Vergence Nystagmus Saccade A saccade is a rapid eye movement (a jump) which is usually conjugate (i.e. both eyes move together in the same direction) and under voluntary control. Broadly speaking the purpose of these movements is to bring images of particular areas of the visual world to fall onto the fovea. Saccades are therefore a major instrument of selective visual attention. It is often convenient (but somewhat inaccurate) to consider both that a saccadic eye movement always occurs in a straight line and also that we do not ‘see’ during these movements. -

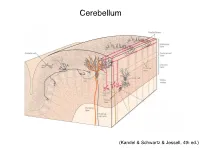

Cerebellum and Activation of the Cerebellum IO ST During Nonmotor Tasks

Cerebellum (Kandel & Schwartz & Jessell, 4th ed.) Granule186 cells are irreducibly smallChapter (6-8 7 μm) stellate cell basket cell outer synaptic layer PC rs cap PC layer grc Go inner 6 μm synaptic layer Figure 7.15 Largest cerebellar neuron occupies more than a 1,000-fold greater volume than smallest neuron. Thin section (~1 μ m) through monkey cerebellar cortex. Purkinje cell body (PC) and nucleus are far larger than those of granule cell (grc). The latter cluster to leave space for mossy fiber terminals to form glomeruli with grc dendritic claws and space for Golgi cells (Go). Note rich network of capillaries (cap). Fine, scat- tered dots are mitochondria. Courtesy of E. Mugnaini. brain ’ s most numerous neuron, this small cost grows large (see also chapter 13). Much of the inner synaptic layer is occupied by the large axon terminals of mossy fibers (figures 7.1 and 7.16). A terminal interlaces with multiple (~15) dendritic claws, each from a different but neighboring granule cell, and forms a complex knot (glomerulus ), nearly as large as a granule cell body (figures 7.1 and 7.16). The mossy fiber axon fires at an unusually high mean rate (up to 200 Hz) and is therefore among the brain’ s thickest (figure 4.6). To match the axon’ s high rate, a terminal expresses 150 active zones, 10 per postsynaptic granule cell (figure 7.16). These sites are capable of driving … and most expensive. 190 Chapter 7 10 4 8 3 9 19 10 10 × 6 × 2 2 4 ATP/s/cell ATP/s/cell ATP/s/m 1 2 0 0 astrocyte astrocyte Golgi cell Golgi cell basket cell basket cell stellate cell stellate cell granule cell granule cell mossy fiber mossy fiber Purkinje cell Purkinje Purkinje cell Purkinje Bergman glia Bergman glia climbing fiber climbing fiber Figure 7.18 Energy costs by cell type. -

Optical Illusion Art As Radical Interface

Perceptual Play: Optical Illusion Art as Radical Interface Julian Oliver, 2008 In 1992 Joachim Sauter and Dirk Lüsebrink presented a work called Zerseher ('Iconoclast') at Ars Electronica, where they were awarded a prize in the Interactive Art category. In this work, audiences were invited to destroy a (digital) copy of an antique painting just by looking at it. Zerseher provides a context for direct manipulation of the visible work. The position and orientation of the viewer's eyes are tracked using a camera which, in turn, directs a digital brush over the surface of the image, smearing pixels around. It's not hard to see why the piece was awarded; here the premise explored in philosophy and poetry, that the gaze might have a mutating or productive power of its own, was explicitly manifested: the mere act of looking had the power to alter (or destroy) the artefact itself. Historically speaking, the idea that the gaze might be a primally destabilising force may have arisen from the fact that seeing itself is not always reliable; that the act of seeing – and perceiving what is seen – is something to be suspicious of. Many works of philosophy and poetry have asserted the primary fragility of perception, particularly as related to the ocular sense. This can be traced back as far as Plato in Western thought, who was early in identifying that what is seen propagates as an object of thought – a mental image – separated from the world and that it is there that interpretation occurs: "The image stands at the junction of a light which comes from the object and another which comes from the gaze".1 In recent times, the study of perception2 has been as active in scienctific thought as it has in philosophy.