Occurrence of Long-Term Depression in the Cerebellar Flocculus During Adaptation of Optokinetic Response Takuma Inoshita, Tomoo Hirano*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cerebellum in Sagittal Plane-Anatomic-MR Correlation: 2

667 The Cerebellum in Sagittal Plane-Anatomic-MR Correlation: 2. The Cerebellar Hemispheres Gary A. Press 1 Thin (5-mm) sagittal high-field (1 .5-T) MR images of the cerebellar hemispheres James Murakami2 display (1) the superior, middle, and inferior cerebellar peduncles; (2) the primary white Eric Courchesne2 matter branches to the hemispheric lobules including the central, anterior, and posterior Dean P. Berthoty1 quadrangular, superior and inferior semilunar, gracile, biventer, tonsil, and flocculus; Marjorie Grafe3 and (3) several finer secondary white-matter branches to individual folia within the lobules. Surface features of the hemispheres including the deeper fissures (e.g., hori Clayton A. Wiley3 1 zontal, posterolateral, inferior posterior, and inferior anterior) and shallower sulci are John R. Hesselink best delineated on T1-weighted (short TRfshort TE) and T2-weighted (long TR/Iong TE) sequences, which provide greatest contrast between CSF and parenchyma. Correlation of MR studies of three brain specimens and 11 normal volunteers with microtome sections of the anatomic specimens provides criteria for identifying confidently these structures on routine clinical MR. MR should be useful in identifying, localizing, and quantifying cerebellar disease in patients with clinical deficits. The major anatomic structures of the cerebellar vermis are described in a companion article [1). This communication discusses the topographic relationships of the cerebellar hemispheres as seen in the sagittal plane and correlates microtome sections with MR images. Materials, Subjects, and Methods The preparation of the anatomic specimens, MR equipment, specimen and normal volunteer scanning protocols, methods of identifying specific anatomic structures, and system of This article appears in the JulyI August 1989 issue of AJNR and the October 1989 issue of anatomic nomenclature are described in our companion article [1]. -

Bilateral Cerebellar Dysfunctions in a Unilateral Meso-Diencephalic Lesion

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.44.4.361 on 1 April 1981. Downloaded from Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 1981, 44, 361-363 Short report Bilateral cerebellar dysfunctions in a unilateral meso-diencephalic lesion D VON CRAMON From the Max-Planck-Institute for Psychiatry, Munich, Germany SUMMARY The clinical syndrome of a 65-year-old patient with a slit-shaped right-sided meso- diencephalic lesion was analysed. A cerebellar syndrome with limb-kinetic ataxia, intention tremor and hypotonicity in all extremities as well as ataxic dysarthria was found. The disruption of the two cerebello-(rubro)-thalamic pathways probably explained the signs of bilateral cere- bellar dysfunction. The uncrossed ascending limb of the right, and the crossed one of the left brachium conjunctivum may have been damaged by the unilateral lesion extending between caudal midbrain and dorsal thalamus. Protected by copyright. Most of the fibres which constitute the superior general hospital where neurological examination cerebellar peduncle leave the cerebellum and showed bilateral miosis, convergent strabism, vertical originate in cells of the dentate nucleus but also gaze paresis on upward gaze with gaze-paretic nystag- arise from neurons of the globose and emboli- mus, flaccid sensori-motor hemiparesis with increased stretch reflexes and Babinski sign on the left side, forme nuclei. The crossed ascending fibres of the and dysmetric movements of the right upper extremity. brachia conjunctiva constitute the major outflow The CT scan showed an acute haemorrhage in the from the cerebellum, they form the cerebello- right mesodiencephalic area. On 19 February 1979 (rubro)-thalamic and dentato-thalamic tracts.' the patient was admitted to our department. -

Differentiation of the Cerebellum 2463

Development 128, 2461-2469 (2001) 2461 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 2001 DEV1660 Inductive signal and tissue responsiveness defining the tectum and the cerebellum Tatsuya Sato, Isato Araki‡ and Harukazu Nakamura* Department of Molecular Neurobiology, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, Seiryo-machi 4-1, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980- 8575, Japan ‡Present address: Department of Neurobiology, University of Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 364, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 11 April 2001 SUMMARY The mes/metencephalic boundary (isthmus) has an Fgf8b repressed Otx2 expression, but upregulated Gbx2 and organizing activity for mesencephalon and metencephalon. Irx2 expression in the mesencephalon. As a result, Fgf8b The candidate signaling molecule is Fgf8 whose mRNA is completely changed the fate of the mesencephalic alar plate localized in the region where the cerebellum differentiates. to cerebellum. Quantitative analysis showed that Fgf8b Responding to this signal, the cerebellum differentiates in signal is 100 times stronger than Fgf8a signal. Co- the metencephalon and the tectum differentiates in the transfection of Fgf8b with Otx2 indicates that Otx2 is a key mesencephalon. Based on the assumption that strong Fgf8 molecule in mesencephalic generation. We have shown by signal induces the cerebellum and that the Fgf8b signal is RT-PCR that both Fgf8a and Fgf8b are expressed, Fgf8b stronger than that of Fgf8a, we carried out experiments to expression prevailing in the isthmic region. The results all misexpress Fgf8b and Fgf8a in chick embryos. Fgf8a did not support our working hypothesis that the strong Fgf8 signal affect the expression pattern of Otx2, Gbx2 or Irx2. -

Neocortex: Consciousness Cerebellum

Grey matter (chips) White matter (the wiring: the brain mainly talks to itself) Neocortex: consciousness Cerebellum: unconscious control of posture & movement brains 1. Golgi-stained section of cerebral cortex 2. One of Ramon y Cajal’s faithful drawings showing nerve cell diversity in the brain cajal Neuropil: perhaps 1 km2 of plasma membrane - a molecular reaction substrate for 1024 voltage- and ligand-gated ion channels. light to Glia: 3 further cell types 1. Astrocytes: trophic interface with blood, maintain blood brain barrier, buffer excitotoxic neurotransmitters, support synapses astros Oligodendrocytes: myelin insulation oligos Production persists into adulthood: radiation myelopathy 3. Microglia: resident macrophages of the CNS. Similarities and differences with Langerhans cells, the professional antigen-presenting cells of the skin. 3% of all cells, normally renewed very slowly by division and immigration. Normal Neurosyphilis microglia Most adult neurons are already produced by birth Peak synaptic density by 3 months EMBRYONIC POSTNATAL week: 0 6 12 18 24 30 36 Month: 0 6 12 18 24 30 36 Year: 4 8 12 16 20 24 Cell birth Migration 2* Neurite outgrowth Synaptogenesis Myelination 1* Synapse elimination Modified from various sources inc: Andersen SL Neurosci & Biobehav Rev 2003 Rakic P Nat Rev Neurosci 2002 Bourgeois Acta Pediatr Suppl 422 1997 timeline 1 Synaptogenesis 100% * Rat RTH D BI E A Density of synapses in T PUBERTY primary visual cortex H at different times post- 0% conception. 100% (logarithmic scale) RTH Cat BI D E A T PUBERTY H The density values equivalent 0% to 100% vary between species 100% but in Man the peak value is Macaque 6 3 RTH 350 x10 synapses per mm BI D E PUBERTY A T The peak rate of synapse H formation is at birth in the 0% macaque: extrapolating to 100% the entire cortex, this Man RTH BI amounts to around 800,000 D E synapses formed per sec. -

Cerebellar Granule Cells in Culture

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 83, pp. 4957-4961, July 1986 Neurobiology Cerebellar granule cells in culture: Monosynaptic connections with Purkinje cells and ionic currents (excitatory postsynaptic potential/patch-clamp) ToMoo HIRANO, YOSHIHIRo KUBO, AND MICHAEL M. WU Department of Neurobiology, Institute of Brain Research, School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan Communicated by S. Hagiwara, March 6, 1986 ABSTRACT Electrophysiological properties of cerebellar tissue was dissociated by triturating with a fire-polished granule cells and synapses between granule and Purkinje cells Pasteur pipette in Ca-free Hanks' balanced salt solution were studied in dissociated cultures. Electrophysiological prop- containing 0.05% DNase and 12 mM MgSO4. The cells were erties of neurons and synapses in the mammalian central centrifuged at 150 x g at 40C and the pelleted cells were nervous system are best studied in dissociated cell cultures resuspended at a concentration of about 106 cells per ml in a because of good target cell visibility, control over the contents defined medium (9). One milliliter ofthe cell suspension from of the extracellular solution, and the feasibility of whole-cell newborn rats was plated first in a Petri dish (3.5 cm in patch electrode recording, which has been a powerful tech- diameter) containing several pieces ofheat-sterilized, poly(L- nique in analyzing biophysical properties of ionic channels in lysine)-coated coverslips, and then 1 ml of fetal cell suspen- small cells. We have applied this whole-cell recording technique sion was added. One-half of the culture medium was ex- to cultured cerebellar granule cells whose electrophysiological changed with fresh medium once a week. -

…Going One Step Further

…going one step further C20 (1017868) 2 Latin A Encephalon Mesencephalon B Telencephalon 31 Lamina tecti B1 Lobus frontalis 32 Tegmentum mesencephali B2 Lobus temporalis 33 Crus cerebri C Diencephalon 34 Aqueductus mesencephali D Mesencephalon E Metencephalon Metencephalon E1 Cerebellum 35 Cerebellum F Myelencephalon a Vermis G Circulus arteriosus cerebri (Willisii) b Tonsilla c Flocculus Telencephalon d Arbor vitae 1 Lobus frontalis e Ventriculus quartus 2 Lobus parietalis 36 Pons 3 Lobus occipitalis f Pedunculus cerebellaris superior 4 Lobus temporalis g Pedunculus cerebellaris medius 5 Sulcus centralis h Pedunculus cerebellaris inferior 6 Gyrus precentralis 7 Gyrus postcentralis Myelencephalon 8 Bulbus olfactorius 37 Medulla oblongata 9 Commissura anterior 38 Oliva 10 Corpus callosum 39 Pyramis a Genu 40 N. cervicalis I. (C1) b Truncus ® c Splenium Nervi craniales d Rostrum I N. olfactorius 11 Septum pellucidum II N. opticus 12 Fornix III N. oculomotorius 13 Commissura posterior IV N. trochlearis 14 Insula V N. trigeminus 15 Capsula interna VI N. abducens 16 Ventriculus lateralis VII N. facialis e Cornu frontale VIII N. vestibulocochlearis f Pars centralis IX N. glossopharyngeus g Cornu occipitale X N. vagus h Cornu temporale XI N. accessorius 17 V. thalamostriata XII N. hypoglossus 18 Hippocampus Circulus arteriosus cerebri (Willisii) Diencephalon 1 A. cerebri anterior 19 Thalamus 2 A. communicans anterior 20 Sulcus hypothalamicus 3 A. carotis interna 21 Hypothalamus 4 A. cerebri media 22 Adhesio interthalamica 5 A. communicans posterior 23 Glandula pinealis 6 A. cerebri posterior 24 Corpus mammillare sinistrum 7 A. superior cerebelli 25 Hypophysis 8 A. basilaris 26 Ventriculus tertius 9 Aa. pontis 10 A. -

Consensus Paper: Experimental Neurostimulation of the Cerebellum

The Cerebellum https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-019-01041-5 CONSENSUS PAPER Consensus Paper: Experimental Neurostimulation of the Cerebellum Lauren N. Miterko1 & Kenneth B. Baker2 & Jaclyn Beckinghausen1 & Lynley V. Bradnam3 & Michelle Y. Cheng4 & Jessica Cooperrider2 & Mahlon R. DeLong5 & Simona V. Gornati6 & Mark Hallett7 & Detlef H. Heck8 & Freek E. Hoebeek6,9 & Abbas Z. Kouzani10 & Sheng-Han Kuo11 & Elan D. Louis12 & Andre Machado2 & Mario Manto13,14 & Alana B. McCambridge15 & Michael A. Nitsche16,17 & Nordeyn Oulad Ben Taib 18 & Traian Popa7,19 & Masaki Tanaka20 & Dagmar Timmann21 & Gary K. Steinberg4,22 & Eric H. Wang4 & Thomas Wichmann5,23 & Tao Xie24 & Roy V. Sillitoe1 # The Author(s) 2019 Abstract The cerebellum is best known for its role in controlling motor behaviors. However, recent work supports the view that it also influences non-motor behaviors. The contribution of the cerebellum towards different brain functions is underscored by its involvement in a diverse and increasing number of neurological and neuropsychiatric conditions including ataxia, dystonia, essential tremor, Parkinson’s disease (PD), epilepsy, stroke, multiple sclerosis, autism spectrum disorders, dyslexia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and schizophrenia. Although there are no cures for these conditions, cerebellar stimula- tion is quickly gaining attention for symptomatic alleviation, as cerebellar circuitry has arisen as a promising target for invasive and non-invasive neuromodulation. This consensus paper brings together experts from the fields of neurophysiology, neurology, and neurosurgery to discuss recent efforts in using the cerebellum as a therapeutic intervention. We report on the most advanced techniques for manipulating cerebellar circuits in humans and animal models and define key hurdles and questions for moving forward. -

Brain Anatomy

BRAIN ANATOMY Adapted from Human Anatomy & Physiology by Marieb and Hoehn (9th ed.) The anatomy of the brain is often discussed in terms of either the embryonic scheme or the medical scheme. The embryonic scheme focuses on developmental pathways and names regions based on embryonic origins. The medical scheme focuses on the layout of the adult brain and names regions based on location and functionality. For this laboratory, we will consider the brain in terms of the medical scheme (Figure 1): Figure 1: General anatomy of the human brain Marieb & Hoehn (Human Anatomy and Physiology, 9th ed.) – Figure 12.2 CEREBRUM: Divided into two hemispheres, the cerebrum is the largest region of the human brain – the two hemispheres together account for ~ 85% of total brain mass. The cerebrum forms the superior part of the brain, covering and obscuring the diencephalon and brain stem similar to the way a mushroom cap covers the top of its stalk. Elevated ridges of tissue, called gyri (singular: gyrus), separated by shallow groves called sulci (singular: sulcus) mark nearly the entire surface of the cerebral hemispheres. Deeper groves, called fissures, separate large regions of the brain. Much of the cerebrum is involved in the processing of somatic sensory and motor information as well as all conscious thoughts and intellectual functions. The outer cortex of the cerebrum is composed of gray matter – billions of neuron cell bodies and unmyelinated axons arranged in six discrete layers. Although only 2 – 4 mm thick, this region accounts for ~ 40% of total brain mass. The inner region is composed of white matter – tracts of myelinated axons. -

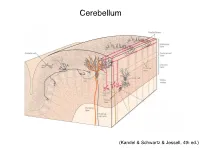

Cerebellum and Activation of the Cerebellum IO ST During Nonmotor Tasks

Cerebellum (Kandel & Schwartz & Jessell, 4th ed.) Granule186 cells are irreducibly smallChapter (6-8 7 μm) stellate cell basket cell outer synaptic layer PC rs cap PC layer grc Go inner 6 μm synaptic layer Figure 7.15 Largest cerebellar neuron occupies more than a 1,000-fold greater volume than smallest neuron. Thin section (~1 μ m) through monkey cerebellar cortex. Purkinje cell body (PC) and nucleus are far larger than those of granule cell (grc). The latter cluster to leave space for mossy fiber terminals to form glomeruli with grc dendritic claws and space for Golgi cells (Go). Note rich network of capillaries (cap). Fine, scat- tered dots are mitochondria. Courtesy of E. Mugnaini. brain ’ s most numerous neuron, this small cost grows large (see also chapter 13). Much of the inner synaptic layer is occupied by the large axon terminals of mossy fibers (figures 7.1 and 7.16). A terminal interlaces with multiple (~15) dendritic claws, each from a different but neighboring granule cell, and forms a complex knot (glomerulus ), nearly as large as a granule cell body (figures 7.1 and 7.16). The mossy fiber axon fires at an unusually high mean rate (up to 200 Hz) and is therefore among the brain’ s thickest (figure 4.6). To match the axon’ s high rate, a terminal expresses 150 active zones, 10 per postsynaptic granule cell (figure 7.16). These sites are capable of driving … and most expensive. 190 Chapter 7 10 4 8 3 9 19 10 10 × 6 × 2 2 4 ATP/s/cell ATP/s/cell ATP/s/m 1 2 0 0 astrocyte astrocyte Golgi cell Golgi cell basket cell basket cell stellate cell stellate cell granule cell granule cell mossy fiber mossy fiber Purkinje cell Purkinje Purkinje cell Purkinje Bergman glia Bergman glia climbing fiber climbing fiber Figure 7.18 Energy costs by cell type. -

Cerebellar Control of Defense Reactions Under Orexin-Mediated Neuromodulation As a Model of Cerebellohypothalamic Interaction

Manuscript submitted to: Volume 1, Issue 1, 89-95. AIMS Neuroscience DOI: 10.3934/Neuroscience.2014.1.89 Received date 1 April 2014, Accepted date 4 June 2014, Published date 10 June 2014 Review article Cerebellar Control of Defense Reactions under Orexin-mediated Neuromodulation as a Model of Cerebellohypothalamic Interaction Masao Ito 1,* and Naoko Nisimaru 1,2 1 RIKEN Brain Science Institute, 2-1 Hirosawa, Wako, Saitama, 315-0198, Japan 2 Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Oita University, 1-1 Idaigaoka, Hasama,Yufu, Oita 879-5593, Japan * Correspondence: Email: [email protected]; Tel: +81-48467-6984: Fax: +81-48467-6975. Abstract: Recent evidence has indicated that, when an animal is exposed to harmful stimuli, hypothalamic orexinergic neurons are activated via the amygdala and in turn tune the neuronal circuits in the spinal cord, brainstem, and an area of the cerebellum (folium-p of the flocculus) by neuromodulation. The animal would then initiate “defense reactions” composed of complex movements and associated cardiovascular responses. To investigate neuronal mechanisms of the defense reactions, Nisimaru et al. (2013) analyzed cardiovascular responses induced by an electric foot shock stimulus to a rabbit and found two major effects. One is redistribution of arterial blood flow from visceral organs to active muscles, and the other is a modest increase in blood pressure. Kainate-induced lesions of folium-p impaired these two effects. Moreover, folium-p Purkinje cells were shown to project to the parabrachial nucleus, one of the major cardiovascular centers in the brainstem. These data indicate that folium-p Purkinje cells regulate cardiovascular defense reactions via parabrachial nucleus under orexin-mediated neuromodulation. -

Neuroimaging Evidence Implicating Cerebellum in Support of Sensory Cognitive Processes Associated with Thirst

Neuroimaging evidence implicating cerebellum in support of sensory͞cognitive processes associated with thirst Lawrence M. Parsons*†, Derek Denton‡, Gary Egan‡, Michael McKinley‡, Robert Shade‡, Jack Lancaster*, and Peter T. Fox* *Research Imaging Center, Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78284; ‡Howard Florey Institute of Experimental Physiology and Medicine, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; and §Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research, P.O. Box 760549, San Antonio, TX 78245-0549 Contributed by Derek A. Denton, December 13, 1999 Recent studies implicate the cerebellum, long considered strictly a and tactile discrimination, kinesthetic sensation, and working motor control structure, in cognitive, sensory, and affective phe- memory, among other processes (6–12). It has been proposed nomenon. The cerebellum, a phylogenetically ancient structure, that the lateral cerebellum may be activated during several has reciprocal ancient connections to the hypothalamus, a struc- motor, perceptual, and cognitive processes specifically because ture important in vegetative functions. The present study investi- of the requirement to monitor and adjust the acquisition of gated whether the cerebellum was involved in vegetative func- sensory data (2, 13). Furthermore, there are reports suggesting tions and the primal emotions engendered by them. Using positron the involvement of posterior vermal cerebellum in affect (14, 15). emission tomography, we examined the effects on the cerebellum The findings implicating the cerebellum in sensory processing of the rise of plasma sodium concentration and the emergence of and emotional states make it of great interest to examine thirst in 10 healthy adults. The correlation of regional cerebral whether the cerebellum has a role in basic vegetative functions blood flow with subjects’ ratings of thirst showed major activation and the primal emotions thus generated, particularly given the in the vermal central lobule. -

On the Function of the Floccular Complex of the Vertebrate Cerebellum: Implications in Paleoneuroanatomy

On the function of the floccular complex of the vertebrate cerebellum: implications in paleoneuroanatomy Sérgio Filipe Ferreira Cardoso Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Paleontologia Orientador: Doutor Rui Alexandre Ferreira Castanhinha Co-orientadores: Doutor Ricardo Miguel Nóbrega Araújo Prof. Doutor Miguel Telles Antunes On the function of the floccular complex of the vertebrate cerebellum: implications in paleoneuroanatomy Sérgio Filipe Ferreira Cardoso Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Paleontologia Orientador: Doutor Rui Alexandre Ferreira Castanhinha Co-orientadores: Doutor Ricardo Miguel Nóbrega Araújo Prof. Doutor Miguel Telles Antunes Successfully defended on 18th November 2015 at FCT-UNL Campus, Portugal, before a juri presided over by: Doutor Paulo Alexandre Rodrigues Roque Legoinha and consisting of: Doutor Gabriel José Gonçalves Martins Doutor Rui Alexandre Ferreira Castanhinha I II Direitos de autor - Copyright Os direitos de autor deste documento pertencem a Sérgio Filipe Ferreira Cardoso, à FCT/UNL, à UNL e à UÉ. A Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, a Universidade Nova de Lisboa e a Universidade de Évora têm o direito, perpétuo e sem limites geográficos, de arquivar e publicar esta dissertação através de exemplares impressos reproduzidos em papel ou de forma digital, ou por qualquer outro meio conhecido ou que venha a ser inventado, e de a divulgar através de repositórios científicos e de admitir a sua cópia e distribuição com objectivos educacionais ou de investigação, não comerciais, desde que seja dado crédito ao autor e editor. Two peer-reviewed abstracts, resulting from this study, were accepted for oral communications (Appendix II). Ferreira-Cardoso, S., Araújo, R., Castanhinha, R., Walsh, S., Martins, R.M.S., Martins, G.G.