New and Amended Rate Source Definitions for the Chilean Peso, Colombian Peso, and Peruvian Sol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Market Peso Exchange As a Mechanism to Place Substantial Amounts of Currency from U.S

United States Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network FinCEN Advisory Subject: This advisory is provided to alert banks and other depository institutions Colombian to a large-scale, complex money laundering system being used extensively by Black Market Colombian drug cartels to launder the proceeds of narcotics sales. This Peso Exchange system is affecting both U.S. financial depository institutions and many U.S. businesses. The information contained in this advisory is intended to help explain how this money laundering system works so that U.S. financial institutions and businesses can take steps to help law enforcement counter it. Overview Date: November Drug sales in the United States are estimated by the Office of National 1997 Drug Control Policy to generate $57.3 billion annually, and most of these transactions are in cash. Through concerted efforts by the Congress and the Executive branch, laws and regulatory actions have made the movement of this cash a significant problem for the drug cartels. America’s banks have effective systems to report large cash transactions and report suspicious or Advisory: unusual activity to appropriate authorities. As a result of these successes, the Issue 9 placement of large amounts of cash into U.S. financial institutions has created vulnerabilities for the drug organizations and cartels. Efforts to avoid report- ing requirements by structuring transactions at levels well below the $10,000 limit or camouflage the proceeds in otherwise legitimate activity are continu- ing. Drug cartels are also being forced to devise creative ways to smuggle the cash out of the country. This advisory discusses a primary money laundering system used by Colombian drug cartels. -

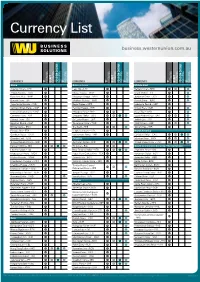

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Colombian Peso Forecast Special Edition Nov

Friday Nov. 4, 2016 Nov. 4, 2016 Mexican Peso Outlook Is Bleak With or Without Trump Buyside View By George Lei, Bloomberg First Word The peso may look historically very cheap, but weak fundamentals will probably prevent "We're increasingly much appreciation, regardless of who wins the U.S. election. concerned about the The embattled currency hit a three-week low Nov. 1 after a poll showed Republican difference between PDVSA candidate Donald Trump narrowly ahead a week before the vote. A Trump victory and Venezuela. There's a could further bruise the peso, but Hillary Clinton wouldn't do much to reverse 26 scenario where PDVSA percent undervaluation of the real effective exchange rate compared to the 20-year average. doesn't get paid as much as The combination of lower oil prices, falling domestic crude production, tepid economic Venezuela." growth and a rising debt-to-GDP ratio are key challenges Mexico must address, even if — Robert Koenigsberger, CIO at Gramercy a status quo in U.S. trade relations is preserved. Oil and related revenues contribute to Funds Management about one third of Mexico's budget and output is at a 32-year low. Economic growth is forecast at 2.07 percent in 2016 and 2.26 percent in 2017, according to a Nov. 1 central bank survey. This is lower than potential GDP growth, What to Watch generally considered at or slightly below 3 percent. To make matters worse, Central Banks Deputy Governor Manuel Sanchez said Oct. Nov. 9: Mexico's CPI 21 that the GDP outlook has downside risks and that the government must urgently Nov. -

Argentina's 2001 Economic and Financial Crisis: Lessons for Europe

Argentina’s 2001 economic and Financial Crisis: Lessons for europe Former Under Secretary of Finance and Chief Advisor to the Minister of the Miguel Kiguel Economy, Argentina; Former President, Banco Hipotecario; Director, Econviews; Professor, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella he 2001 Argentine economic and financial banks and international reserves—was not enough crisis has many parallels with the problems to cover the financial liabilities of the consolidated Tthat some European countries are facing to- financial system . This was a major source of vulner- day . Prior to the crisis, Argentina was suffering a ability, especially because there is ample evidence deep recession, large levels of debt, twin deficits in that an economy without a lender of last resort is the fiscal and current accounts, and the country inherently unstable and subject to bank runs . This had an overvalued currency but devaluation was is not a pressing issue in Europe, where the Euro- not an option . pean Central Bank can provide liquidity to banks . Argentina tried in vain to restore its competitive- The trigger for the crisis in Argentina was a run on ness through domestic deflation and improving the banking system as people realized that there its solvency by increasing its fiscal accounts in were not enough dollars in the system to cover all the midst of a recession . The country also tried to the deposits . As the run intensified, the Argentine avoid a default first by resorting to a large financial government was forced to introduce a so-called package from the multilateral institutions (the so “fence” to control the outflow of deposits . -

Macroeconomic Situation Food Prices and Consumption

Dr. Eugenia Muchnik, Manager Agroindustrial Dept., Fundacion Chile, Santiago, Chile Loreto Infante, Agricultural Economist, Assistant CHILE Tomas Borzutzky; Agricultural Economist, Agroindustrial Dept., Fundacion Chile Macroeconomic Situation price index had a -1 percent reduction. Inflation rates and food price fter 2000, in which the Chilean economy exhibited increases are not expected to differ much during 2003 unless there are an encouraging growth rate of 5.4 percent, 2001 unexpected external shocks. The proximity of Argentina and the showed a slowdown, reaching a rate of 2.8 percent, reduction of its export prices as a result of a drastic devaluation may in with growth led by fisheries and energy. Agricultural fact result in price reductions; prices of agricultural inputs have been AGDP grew by 4.7 percent, double the average growth declining, while there are no reasons to expect important changes in rate for the economy as a whole. On the low end of the spectrum, the Chilean real exchange rate. manufacturing experienced a negative growth of -0.3 percent, and in general, the slowest economic growth took place in sectors more dependent on the behavior of domestic demand. There were two Food Processing and Marketing events that took place in the second half of 2001 that changed the At present, the most dynamic sectors in the food processing industry external scenario of the global economy, increasing uncertainty in are wine production and the manufacture of meats and dairy products. financial markets and reducing global growth: the terrorist attacks of In the wine industry, as a result of the rapid expansion of vineyard September 11 and the rapid deterioration of Argentina’s economy. -

Chile: a Macroeconomic Analysis Lee Moore Jose Stevenson Rico X

Chile: A Macroeconomic Analysis Lee Moore Jose Stevenson Rico X I. Chile: A Macroeconomic Success Story In the last decade, Chile has gained a reputation as one of the most stable economies in Latin America. It has implemented a set of fiscal and monetary policies that encourage privatization, focus on exports, encourage high levels of foreign trade and generally promote stabilization. These policies seem to have worked very well for the country, evidenced by steady and sometimes very high growth rates. From 1985-2000, GDP growth averaged 6.6%. Chile is also famous for its privatized pension system, which has been a model for other Latin American countries, and countries around the world. Workers invest their pensions in domestic markets, which has added roughly $36 billion into the economy, a significant source of investment capital for the stock market.1 Chile experienced a slight recession in 1998-99, due to shocks from the Asian financial crisis of 1997. With increasing unemployment and inflation rates, Chile struggled to maintain its policy of keeping the peso fixed to the US dollar within a band width of 25%.2 In September of 1999, Chile let its peso float, increasing its leeway in monetary policy decisions. Below is a brief history of the macroeconomic indicators, leading up to and beyond the floatation policy, which played a significant role in shaping Chile’s recent economy. Figure 1: Chile’s Real GDP (’96-01) II. Recent Macroeconomic Performance Chile's Real GDP GDP: After a steadily increasing GDP throughout the 80’s and 90’s, Chile’s GDP 37,000,000 36,000,000 growth took a downward turn by –1.1% in 35,000,000 3 34,000,000 1999. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

October 2006 Millions of U.S

I. TOTAL FOREIGN EXCHANGE VOLUME, October 2006 Millions of U.S. Dollars AVERAGE DAILY VOLUME Current Dollar Change Percentage Change Instrument Amount Reported over Previous Year over Previous Year Spot transactions 246,318 34,519 16.3 Outright forwards 82,443 9,253 12.6 Foreign exchange swaps 159,153 4,019 2.6 OTC foreign exchange options 45,782 9,051 24.6 Total 533,696 56,842 11.9 TOTAL MONTHLY VOLUME Current Dollar Change Percentage Change Instrument Amount Reported over Previous Year over Previous Year Spot transactions 5,418,907 1,182,971 27.9 Outright forwards 1,813,721 349,905 23.9 Foreign exchange swaps 3,501,389 398,764 12.9 OTC foreign exchange options 1,007,167 272,531 37.1 Total 11,741,184 2,204,171 23.1 Note: The lower table reports notional amounts of total monthly volume adjusted for double reporting of trades between reporting dealers; there were twenty trading days in October 2005 and twenty-two in October 2006. Survey of North American Foreign Exchange Volume 55 2a. SPOT TRANSACTIONS, Average Daily Volume, October 2006 Millions of U.S. Dollars Counterparty Reporting Other Other Financial Nonfinancial Currency Pair Dealers Dealers Customers Customers Total U.S. DOLLAR VERSUS Euro 13,237 38,775 19,355 5,260 76,627 Japanese yen 6,461 16,844 10,186 2,450 35,941 British pound 4,614 13,604 10,135 2,165 30,518 Canadian dollar 3,686 7,535 4,218 1,579 17,018 Swiss franc 2,863 7,727 6,426 1,036 18,052 Australian dollar 1,531 4,119 2,258 704 8,612 Argentine peso 21 23 13 10 67 Brazilian real 430 681 434 181 1,726 Chilean peso 132 156 153 42 483 Mexican peso 1,801 3,499 1,650 793 7,743 All other currencies 1,902 4,661 4,543 2,548 13,654 EURO VERSUS Japanese yen 1,977 5,438 4,326 360 12,101 British pound 959 2,801 1,149 634 5,543 Swiss franc 1,241 3,458 2,121 423 7,243 ALL OTHER CURRENCY PAIRS 1,419 5,077 2,496 1,998 10,990 Totala 42,274 114,398 69,463 20,183 246,318 2b. -

The Cuban Convertible Peso

The Cuban Convertible Peso A Redefinitionof Dependence MARK PIPER T lie story of Cuba’s achievement of nationhood and its historical economic relationship with the United States is an instructive example of colonialism and neo-colonial dependence. From its conquest in 1511 until 1898. Cuba was a colony of the Spanish Crown, winning independence after ovo bloody insurgencies. Dtiring its rise to empire, the U.S. acquired substantial economic interest on the island and in 1898 became an active participant in the ouster of the governing Spanish colonial power. As expressed in his poem Nuesrra America,” Ctiban nationalist José Marti presciently feared that the U.S. participation w’ould lead to a new type ofcolonialism through ctiltural absorption and homogenization. Though the stated American goal of the Spanish .Arncrican Var was to gain independence for Cuba, after the Spanish stirrender in July 189$ an American military occupation of Cuba ensued. The Cuban independence of May1902 vas not a true independence, but by virtue of the Platt Amendmentw’as instead a complex paternalistic neo-eolonial program between a dominant American empire and a dependent Cuban state. An instrument ot the neo colonial program tvas the creation of a dependent Cuban economy, with the imperial metropole economically dominating its dependent nation-state in a relationship of inequality. i’o this end, on 8 December 189$, American president William McKinley isstied an executive order that mandated the usc of the U.S. dollar in Cuba and forced the withdrawing from circulation of Spanish colonial currency.’ An important hallmark for nationalist polities is the creation of currency. -

The Giant Sucking Sound: Did NAFTA Devour the Mexican Peso?

J ULY /AUGUST 1996 Christopher J. Neely is a research economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Kent A. Koch provided research assistance. This article examines the relationship The Giant between NAFTA and the peso crisis of December 1994. First, the provisions of Sucking Sound: NAFTA are reviewed, and then the links between NAFTA and the peso crisis are Did NAFTA examined. Despite a blizzard of innuendo and intimation that there was an obvious Devour the link between the passage of NAFTA and Mexican Peso? the peso devaluation, NAFTA’s critics have not been clear as to what the link actually was. Examination of their argu- Christopher J. Neely ments and economic theory suggests two possibilities: that NAFTA caused the Mex- t the end of 1993 Mexico was touted ican authorities to manipulate and prop as a model for developing countries. up the value of the peso for political rea- A Five years of prudent fiscal and mone- sons or that NAFTA’s implementation tary policy had dramatically lowered its caused capital flows that brought the budget deficit and inflation rate and the peso down. Each hypothesis is investi- government had privatized many enter- gated in turn. prises that were formerly state-owned. To culminate this progress, Mexico was preparing to enter into the North American NAFTA Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with NAFTA grew out of the U.S.–Canadian Canada and the United States. But less than Free Trade Agreement of 1988.1 It was a year later, in December 1994, investors signed by Mexico, Canada, and the United sold their peso assets, the value of the Mex- States on December 17, 1992. -

Causes and Lessons of the Mexican Peso Crisis

Causes and Lessons of the Mexican Peso Crisis Stephany Griffith-Jones IDS, University of Sussex May 1997 This study has been prepared within the UNU/WIDER project on Short- Term Capital Movements and Balance of Payments Crises, which is co- directed by Dr Stephany Griffith-Jones, Fellow, IDS, University of Sussex; Dr Manuel F. Montes, Senior Research Fellow, UNU/WIDER; and Dr Anwar Nasution, Consultant, Center for Policy and Implementation Studies, Indonesia. UNU/WIDER gratefully acknowledges the financial contribution to the project by the Government of Sweden (Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency - Sida). CONTENTS List of tables and charts iv Acknowledgements v Abstract vi I Introduction 1 II The apparently golden years, 1988 to early 1994 6 III February - December 1994: The clouds darken 15 IV The massive financial crisis explodes 24 V Conclusions and policy implications 31 Bibliography 35 iii LIST OF TABLES AND CHARTS Table 1 Composition (%) of Mexican and other countries' capital inflows, 1990-93 8 Table 2 Mexico: Summary capital accounts, 1988-94 10 Table 3 Mexico: Non-resident investments in Mexican government securities, 1991-95 21 Table 4 Mexico: Quarterly capital account, 1993 - first quarter 1995 (in millions of US dollars) 22 Table 5 Mexican stock exchange (BMV), 1989-1995 27 Chart 1 Mexico: Real effective exchange rate (1980=100) 7 Chart 2 Current account balance (% of GDP) 11 Chart 3 Saving-investment gap and current account 12 Chart 4 Stock of net international reserves in 1994 (in millions of US dollars) 17 Chart 5 Mexico: Central bank sterilised intervention 18 Chart 6 Mexican exchange rate changes within the exchange rate band (November 1991 through mid-December 1994) 19 Chart 7 Mexican international reserves and Tesobonos outstanding 20 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank UNU/WIDER for financial support for this research which also draws on work funded by SIDA and CEPAL. -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy