The Giant Sucking Sound: Did NAFTA Devour the Mexican Peso?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Years of the Silver Standard in Mexico: Evidence of Purchasing Power Parity with the United States

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Final Years of the Silver Standard in Mexico: Evidence of Purchasing Power Parity with The United States Bojanic, Antonio N. 2 May 2011 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/45535/ MPRA Paper No. 45535, posted 27 Mar 2013 02:12 UTC final years of the silver standard in mexico: evidence of purchasing power parity with the united states Antonio N. Bojanic* Professor of Economics / CENTRUM – Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú Urbanización – Los Alamos de Monterrico – Surco, Perú ABSTRACT RESUMO This paper focuses on the use of silver as Este artigo enfoca o uso da prata como padrão a monetary standard in Mexico during monetário no México, durante aproximada- approximately the last three decades of the mente as três últimas décadas do século XIX nineteenth century and the first decade of e primeira década do século XX. Durante the twentieth century. During this period, esse período, vários eventos ocorreram no several events occurred in the market for mercado de prata, que afetaram os países silver that affected those countries attached atrelados a este metal. Estes eventos causa- to this metal. These events caused some ram alguns destes países a abandonar a prata of these countries to abandon silver for para o bem e adotar outros tipos de regime good and adopt other types of monetary monetário. México e alguns outros, preferiu arrangements. Mexico and a few others ficar com ele. As razões desta decisão são chose to stay with it.The reasons behind this analisados. Além disso prova, que apoia a decision are analyzed. Additionally, evidence teoria da paridade do poder de compra entre that supports the theory of purchasing power o México e os Estados Unidos são também parity between Mexico and the United States apresentados e analisados. -

Structure of the Mexican Rice Industry: Implications for Strategic Planning

STRUCTURE OF THE MEXICAN RICE INDUSTRY: IMPLICATIONS FOR STRATEGIC PLANNING Victoria Salin, Gary Williams, Michael Haigh, Jaime Málaga Jose Carlos Madriñán, Katharine Sheaff* TAMRC International Market Research Report No. IM 2-00 February 2000 * Victoria Salin, Gary Williams, Michael Haigh, Jaime Málaga and Jose Carlos Madriñán, Katharine Sheaff are Assistant Professor, Professor and Director of the Texas Agricultural Market Research Center, Assistant Professor, Assistant Research Scientist, Graduate Research Assistant and Graduate Research Assistant, respectively, in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas. STRUCTURE OF THE MEXICAN RICE INDUSTRY: IMPLICATIONS FOR STRATEGIC PLANNING Texas Agricultural Market Research Center (TAMRC) International Market Research Report No. IM 2- 00, February 2000 by Victoria Salin, Gary Williams, Michael Haigh, Jaime Malága, Jose Carlos Madriñán and Katharine Sheaff. The final report of research reported here was funded in part by the U.S. Rice Producers Association, Houston, Texas under contract. ABSTRACT: This is the second of two reports on the Mexican rice market prepared for the U.S. Rice Producers Association by the Texas Agricultural Market Research Center. The reports provide important insights on the opportunities and challenges for future growth of U.S. rice exports to Mexico, particularly with the potential for NAFTA-induced tariff reductions to alter the competitive position of U.S. rice in Mexico. This study explores and analyzes the current structure of the Mexican rice market and derives implications and provides recommendations to guide strategic planning. This report also serves as background to the first report, an in-depth statistical assessment of the logistics and transportation system for U.S.-Mexico rice trade and the impact that changes in Mexican tariffs will have on that trade. -

Policy Response to Crises in Latin America

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE ROAD TO REDEMPTION: POLICY RESPONSE TO CRISES IN LATIN AMERICA Carlos A. Vegh Guillermo Vuletin Working Paper 20675 http://www.nber.org/papers/w20675 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2014 Paper prepared for the 2013 IMF Annual Research Conference in honor of Stanley Fischer's 70th birthday. We are extremely grateful to Julia Ruiz Pozuelo and Collin Rabe for research assistance. On a personal note, Vegh owes a huge debt of gratitude to Stan for 20 years of unwavering mentorship, co-authorship, and support (dating back to Stan's arrival at the IMF in September 1994). Stan is one of those rare individuals who combines truly remarkable professional credentials with equally astounding personal qualities. Our profuse thanks to Vittorio Corbo as well as to two referees and the editors of this Journal for extremely helpful comments and suggestions. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2014 by Carlos A. Vegh and Guillermo Vuletin. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Road to Redemption: Policy Response to Crises in Latin America Carlos A. Vegh and Guillermo Vuletin NBER Working Paper No. -

The Making of a Crisis in Mexico: an Inductive Analysis of Media

The Making of a Crisis in Mexico: An Inductive Analysis of Media Sentiment and Information Cascades on the Value of the Mexican Peso during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis By ©2014 Lisa M. Vachalek Submitted to the Department of Latin American & Caribbean Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Chairperson: ________________________________ Dr. Melissa H. Birch Committee Members: ________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Kuznesof ________________________________ Dr. Brent E. Metz Date Defended: 4/22/14 The Thesis Committee for Lisa M. Vachalek certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Making of a Crisis in Mexico: An Inductive Analysis of Media Sentiment and Information Cascades on the Value of the Mexican Peso during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis Chairperson: ________________________________ Dr. Melissa H. Birch Date approved: 6/10/14 ii Abstract In the two decades prior to the 2008 financial crisis, the Mexican government pursued policies aimed at liberalizing markets, while simultaneously trying to ensure the stability of the peso. These policies consisted of monetary and fiscal controls to keep inflation low and free trade agreements to reduce Mexico’s dependence on the United States. The policies significantly reduced the country’s public deficit and were implemented in hopes that they would help reduce the country’s exposure to currency crises. Yet, despite all provisions the Mexican government put in place, the country’s peso still lost two percent of its value in the first three days following the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, the US-based investment firm. -

Black Market Peso Exchange As a Mechanism to Place Substantial Amounts of Currency from U.S

United States Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network FinCEN Advisory Subject: This advisory is provided to alert banks and other depository institutions Colombian to a large-scale, complex money laundering system being used extensively by Black Market Colombian drug cartels to launder the proceeds of narcotics sales. This Peso Exchange system is affecting both U.S. financial depository institutions and many U.S. businesses. The information contained in this advisory is intended to help explain how this money laundering system works so that U.S. financial institutions and businesses can take steps to help law enforcement counter it. Overview Date: November Drug sales in the United States are estimated by the Office of National 1997 Drug Control Policy to generate $57.3 billion annually, and most of these transactions are in cash. Through concerted efforts by the Congress and the Executive branch, laws and regulatory actions have made the movement of this cash a significant problem for the drug cartels. America’s banks have effective systems to report large cash transactions and report suspicious or Advisory: unusual activity to appropriate authorities. As a result of these successes, the Issue 9 placement of large amounts of cash into U.S. financial institutions has created vulnerabilities for the drug organizations and cartels. Efforts to avoid report- ing requirements by structuring transactions at levels well below the $10,000 limit or camouflage the proceeds in otherwise legitimate activity are continu- ing. Drug cartels are also being forced to devise creative ways to smuggle the cash out of the country. This advisory discusses a primary money laundering system used by Colombian drug cartels. -

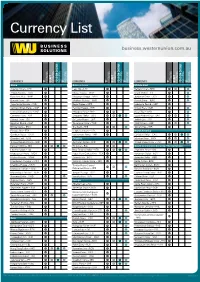

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Mexico: a Decade of Falling Inequality: Market Forces Or State Action? Gerardo Esquivel, Nora Lustig, and John Scott

07-0410-2 CH 7:Cohen-Easterly 3/17/10 8:47 PM Page 175 7 Mexico: A Decade of Falling Inequality: Market Forces or State Action? gerardo esquivel, nora lustig, and john scott exico is among the most unequal countries in the world.1 However, it is Mmaking progress in becoming less unequal: from 1996 to 2006, Mexico’s Gini coefficient fell from 0.543 to 0.498 (or by 0.8 percent a year),2 and from 2000 to 2006 it fell by 1 percent a year.3 The decline in inequality coincided with 1. The authors are grateful to participants in the UNDP project “Markets, the State, and the Dynam- ics of Inequality in Latin America,” coordinated by Nora Lustig and Luis Felipe López Calva, as well as to participants in seminars at the United Nations offices in New York and Mexico City, the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association meeting in Rio de Janeiro, and the Latin American Studies Associa- tion meeting in Rio de Janeiro. We also are very grateful to Mary Kwak and anonymous reviewers for their very useful comments and suggestions and to Fedora Carbajal as well as Edith Cortés, Francisco Islas, and Mariellen Malloy Jewers for their outstanding research assistance. 2. The Gini reported in this paragraph is calculated by using total income (which includes monetary income and nonmonetary income, such as the imputed value of owner-occupied housing and auto- consumption, but does not include capital gains). The decomposition of income inequality by source pre- sented in this chapter uses current monetary income (which excludes capital gains and nonmonetary income). -

Financial and Real Markets Pull Each Other Down; How Can Policy Reverse This?

SCHWARTZ CENTER FOR ECONOMIC POLICY ANALYSIS THE NEW SCHOOL WORKING PAPER 2009-10 After Hubris, Smoke and Mirrors, the Downward Spiral: Financial and Real Markets Pull Each Other Down; How Can Policy Reverse This? Edward Nell and Willi Semmler Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis Department of Economics The New School for Social Research 6 East 16th Street, New York, NY 10003 www.economicpolicyresearch.org Suggested Citation: Nell, Edward and Semmler, Willi. (2009) “After Hubris, Smoke and Mirrors, MAY the Downward Spiral: Financial and Real Markets Pull Each Other Down; How Can Policy Reverse This?” Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis and Department of Economics, 2009 The New School for Social Research, Working Paper Series. 2 Constellations Volume 16, Number 2, 2009 AFTER HUBRIS, SMOKE AND MIRRORS, THE DOWNWARD SPIRAL: Financial and real markets pull each other down; how can policy reverse this? Edward Nell and Willi Semmler 1. Introduction Starting in the 1980s, the liberalization of capital markets intensified under the influence of largely conservative governments. But the conservatives were not alone; political liberals tended to agree with the general push for deregulation. A new consensus formed, hailing the magic of markets.i The Clinton Administration was cautious, but tended to agree, at least up to a point. Bush II pushed deregulation and market worship to new heights. Yet right from the beginning, many countries fell into major episodes of financial instability, as boom and bust cycles blossomed, taking a devastating toll on economic activity. There was the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, the US Crash of 1987, the Japanese real estate and stock market crisis (and trap) in the 1990s, the British Housing crash in 1991, the Mexican Peso Crisis of 1994, the long-running Russian crisis of the mid-90s, the Asian Crisis of 1997/8, the High Tech Crash in the US Stock Market in 2000, and the Argentinian Crisis in 2002 among many others, large and small. -

Colombian Peso Forecast Special Edition Nov

Friday Nov. 4, 2016 Nov. 4, 2016 Mexican Peso Outlook Is Bleak With or Without Trump Buyside View By George Lei, Bloomberg First Word The peso may look historically very cheap, but weak fundamentals will probably prevent "We're increasingly much appreciation, regardless of who wins the U.S. election. concerned about the The embattled currency hit a three-week low Nov. 1 after a poll showed Republican difference between PDVSA candidate Donald Trump narrowly ahead a week before the vote. A Trump victory and Venezuela. There's a could further bruise the peso, but Hillary Clinton wouldn't do much to reverse 26 scenario where PDVSA percent undervaluation of the real effective exchange rate compared to the 20-year average. doesn't get paid as much as The combination of lower oil prices, falling domestic crude production, tepid economic Venezuela." growth and a rising debt-to-GDP ratio are key challenges Mexico must address, even if — Robert Koenigsberger, CIO at Gramercy a status quo in U.S. trade relations is preserved. Oil and related revenues contribute to Funds Management about one third of Mexico's budget and output is at a 32-year low. Economic growth is forecast at 2.07 percent in 2016 and 2.26 percent in 2017, according to a Nov. 1 central bank survey. This is lower than potential GDP growth, What to Watch generally considered at or slightly below 3 percent. To make matters worse, Central Banks Deputy Governor Manuel Sanchez said Oct. Nov. 9: Mexico's CPI 21 that the GDP outlook has downside risks and that the government must urgently Nov. -

Bloomberg Dollar Index

BLOOMBERG DOLLAR INDEX 2017 REBALANCE 2017 REBALANCE HIGHLIGHTS • Indian rupee added 2017 BBDXY WEIGHTS • Brazilian real removed Euro 3.0% Japanese Yen 3.8% 2.1% Canadian Dollar • Euro maintains largest weight 4.4% 5.1% Mexican Peso • Australian dollar largest percentage weight 31.6% British Pound 10.6% decrease Australian Dollar 10.0% Swiss Franc 17.9% • British pound largest percentage weight increase 11.5% South Korean Won Chinese Renminbi • Mexican peso’s weight continues to increase YoY Indian Rupee since 2007 STEPS TO COMPUTE 2017 MEMBERS & WEIGHTS Fed Reserve’s BIS Remove pegged Trade Data Liquidity Survey currencies to USD Remove currency Set Cap exposure Average liquidity positions under to Chinese & trade weights 2% renminbi to 3% Bloomberg Dollar Index Members & Weights 2017 TARGET WEIGHTS- BLOOMBERG DOLLAR INDEX Currency Name Currency Ticker 2017 Target Weight Euro EUR 31.56% Japanese Yen JPY 17.94% Currency % Change from 2016 to 2017 Indian rupee 2.090% *added Canadian Dollar CAD 11.54% British pound 1.128% South Korean won 0.382% British Pound GBP 10.59% Mexican peso 0.084% Canadian dollar 0.064% Mexican Peso MXN 9.95% Swiss franc 0.019% Australian Dollar AUD 5.12% China renminbi 0.000% Euro -0.195% Swiss Franc CHF 4.39% Japanese yen -0.510% Australian dollar -0.978% South Korean Won KRW 3.81% Brazil real -2.083% *deleted Chinese Renminbi CNH 3.00% Indian Rupee INR 2.09% GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION OF MEMBER CURRENCIES GLOBAL 21.50% Americas 46.54% Asia/Pacific 31.96% EMEA 11.93% APAC EMEA AMER 9.39% 9.44% 6.54% Japanese Yen -

Mexico Market Update

Singapore: Hotel Market Market Report - March 2019 MARKET REPORT Mexico Market Update AUGUST 2020 Mexico - Market Update Market Report - August 2020 Mexican Tourist Outlook 2020 The following analysis will examine the current state of the With more than 11,100 km of coastline and landscape Mexican economy, the tourism sector, and the evolution that varies from desert to mountains and rainforests, as of variables that have a tangible influence on the hotel well as an abundant cultural heritage that includes well- industry in Mexico. preserved ancient indigenous cities, Mexico has a privileged geographical location that appeals to its North American Size of the Mexican Hotel Industry neighbors. There should be no doubt about the economic importance of tourism for Mexico. In 2019, 44.7 million foreign tourists Number of Rooms visited Mexico and the total income for this concept Country Number of Rooms amounted to 24.6 billion dollars. In that same year, Mexico 808,139 Mexico was ranked number 7 worldwide for the number of Brazil 541,314 international tourists (OMT). The sector directly accounts Colombia 307,458 for an 8.7% share of the Mexican GDP and provides Perú 304,640 employment for 2.3 million people (2018). Tourism provides 6% of the total amount of work in the economy and is in Argentina 118,858 first place as a youth-employer sector, as well as in second Ecuador 74,173 place for women-employer sector. Costa Rica 57,233 Chile 45,112 Tourism’s share in national GDP 2011-2018 Source: DATATUR, MINCETUR, REPORTUR, SERNATUR, EMBRATUR 8.75% 8.70% 8.70% Mexico occupies the largest share in number of rooms, 8.65% 8.60% 8.60% 8.60% when compared to Central and South American countries. -

S. V. Ananthakrishna

Healing Initiative Leadership Linkage (HILL) Student Magazine: MEXICO World without Borders Monthly update: <Date> Current News Host Editor Country Editor: Insert picture Type the matter……………. Music Art Sports Youth Excellence & Leader: What is catching the attention of your youth? The craze of social media has appeared to have gripped the attention of teens of Mexico. Students take up Scouting and Guiding very actively. The Mexican Youth Athenaeum, later known as the Athenaeum of Mexico, was a Mexican civil association founded on October 28, 1909 with the purpose of working in favor of culture and art, by means of organization public meetings and debates.The members of the Athenaeum gave to Mexican education system a wider vision which rejected racist biological determinism and which found a solution for the cost of social adjustment problem generated by the processes which change society as industrialization or urbanization. Festivals Festival Sayulita. Candlemas - Día de la Candelaría. Constitution Day - Día de la Constitución. Zona Maco. Valentine's Day - Día del Amor y la Amistad. Carnival - Carnaval. Flag Day - Día de la Bandera. Conferences mexHIC 2014, Mexico Mining forum 2017, MexHIC 2017 Healing Initiative Leadership Linkage (HILL) Student Magazine World without Borders Strategy Country challenges and opportunities Constitution rights and Duties Challenges: Freedom of speech, religion,petition, legal rights — yet it goes farther, guaranteeing Poverty Eradication Mexicans the right to a good job (Article 123), decent housing, and health Almost 33.2% of the current population of protection and care (Article 4). And the Mexico lives with less than $5 per day in aforementioned Article 123 spells out Mexico.