Monetary and Exchange Rate Reform in Cuba: Lessons from Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuba's Food & Agriculture Situation Report, USDA, 2008

Cuba’s Food & Agriculture Situation Report by Office of Global Analysis, FAS, USDA March 2008 Table of Contents Page Executive Summary........................................................................................................................ 1 Cuba’s Food & Agriculture Situation Report ................................................................................. 3 The Historical Context Underlying U.S.–Cuban Relations..................................................... 3 Economic Background.............................................................................................................4 Cuba’s Natural Resource Base and Demographic Characteristics .......................................... 8 Population, Food Consumption and Nutrition Issues ............................................................ 14 Tourism and the Demand for Agricultural Products.............................................................. 17 Cuba’s Market Infrastructure and the Role of Institutions in Cuba’s Food and Agricultural Sector............................................................................................................ 18 Cuba’s International Trade Situation..................................................................................... 29 Other Observations ................................................................................................................ 33 Summary and Conclusions .................................................................................................... 33 Addendum -

Meetings & Incentives

MOVES PEOPLE TO BUSINESS TRAVEL & MICE Nº 37 EDICIÓN ESPECIAL FERIAS 2016-2017 / SPECIAL EDITION SHOWS 2016-2017 5,80 € BUSCANDO América Meetings & Incentives Edición bilingüe Bilingual edition 8 PRESENTACIÓN INTRODUCTION Buscando América. Un Nuevo Searching for America. A New Mundo de oportunidades 8 World of Opportunities 9 NORTE Y CENTRO NORTH AND CENTRAL Belice 16 Belize 16 Costa Rica 18 Costa Rica 19 El Salvador 22 El Salvador 22 14 Guatemala 24 Guatemala 24 Honduras 28 Honduras 28 México 30 Mexico 30 Nicaragua 36 Nicaragua 36 Panamá 40 Panama 40 CARIBE CARIBEAN Cuba 48 Cuba 48 Jamaica 52 Jamaica 52 Puerto Rico 54 Puerto Rico 54 46 República Dominicana 58 Dominican Republic 58 SUDAMÉRICA SOUTH AMERICA Argentina 64 Argentina 64 Bolivia 70 Bolivia 70 Brasil 72 Brazil 72 62 Chile 78 Chile 78 Colombia 82 Colombia 82 Ecuador 88 Ecuador 88 Paraguay 92 Paraguay 92 Perú 94 Peru 94 Uruguay 98 Uruguay 99 Venezuela 102 Venezuela 102 104 TURISMO RESPONSABLE SUSTAINABLE TOURISM 106 CHECK OUT Un subcontinente cada vez más An increasingly consolidated consolidado en el segmento MICE continent in the MICE segment Txema Txuglà Txema Txuglà MEET IN EDICIÓN ESPECIAL FERIAS 2016-2017 / SPECIAL EDITION SHOWS 2016-2017 EDITORIAL Natalia Ros EDITORA Fernando Sagaseta DIRECTOR Te busco y sí te I search for you encuentro and I find you «Te estoy buscando, América… Te busco y no te encuentro», “ I am searching for you America… I am searching for you but cantaba en los 80 el panameño Rubén Blades, por más señas I can’t find you ”, sang the Panamanian Rubén Blades in the ministro de Turismo de su país entre 2004 y 2009. -

Birding Tour Cuba: General Information

BIRDING TOUR CUBA: GENERAL INFORMATION www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | INFORMATION Cuba Passports and visa Your passport must be valid for at least six months beyond departure. A tourist visa is compulsory for entry into Cuba. This is valid for 30 days from the day of arrival. Clients staying for a longer duration may extend these locally via the Cuban embassy. If you are traveling to another country from Cuba and then returning, you will need another tourist visa in order to re-enter the country. Please ensure you have your tourist visa correctly completed before check-in at the airport, as it will be requested with your ticket and passport at check-in. While you are in Cuba you must retain the tear-off part of the visa given to you by customs, as it will be required on departure. Tourist card A tourist card needs to be completed when visiting Cuba. Health requirements There are no compulsory vaccinations required for Cuba, but the following are sometimes recommended: Tetanus, Polio, Hepatitis A, and Typhoid. Please check with your doctor for the most up-to-date information. We strongly advise you to read the Center for Disease Control advice on Cuba, at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/cuba. Your health while in Cuba Cuba’s health facilities are good, and some of the larger hotels have their own doctor on site. International clinics can be found in all the main resorts as well as in Havana, Trinidad, Santiago de Cuba, and Cienfuegos. Mosquitoes can be a problem. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009

16 April 2009 OpenȱSourceȱCenter Report Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009 Raul Castro has overhauled the leadership of top government bodies, especially those dealing with the economy, since he formally succeeded his brother Fidel as president of the Councils of State and Ministers on 24 February 2008. Since then, almost all of the Council of Ministers vice presidents have been replaced, and more than half of all current ministers have been appointed. The changes have been relatively low-key, but the recent ousting of two prominent figures generated a rare public acknowledgement of official misconduct. Fidel Castro retains the position of Communist Party first secretary, and the party leadership has undergone less turnover. This may change, however, as the Sixth Party Congress is scheduled to be held at the end of this year. Cuba's top military leadership also has experienced significant turnover since Raul -- the former defense minister -- became president. Names and photos of key officials are provided in the graphic below; the accompanying text gives details of the changes since February 2008 and current listings of government and party officeholders. To view an enlarged, printable version of the chart, double-click on the following icon (.pdf): This OSC product is based exclusively on the content and behavior of selected media and has not been coordinated with other US Government components. This report is based on OSC's review of official Cuban websites, including those of the Cuban Government (www.cubagob.cu), the Communist Party (www.pcc.cu), the National Assembly (www.asanac.gov.cu), and the Constitution (www.cuba.cu/gobierno/cuba.htm). -

Cuba Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Cuba Country Report Status Index 1-10 4.13 # 104 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 3.62 # 107 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 4.64 # 93 of 129 Management Index 1-10 3.67 # 108 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Cuba Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Cuba 2 Key Indicators Population M 11.3 HDI 0.780 GDP p.c. $ - Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.0 HDI rank of 187 59 Gini Index - Life expectancy years 78.9 UN Education Index 0.857 Poverty3 % - Urban population % 75.2 Gender inequality2 0.356 Aid per capita $ 5.8 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary In February 2008, Army General Raúl Castro (born 1931) became president of the Council of State and the Council of Ministers, formally replacing his brother, Fidel Castro. In April 2011, Raúl Castro became first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba, also replacing his brother Fidel. -

Culture Box of Cuba

CUBA CONTENIDO CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................3 Introduction .................................6 Items .............................................8 More Information ........................89 Contents Checklist ......................108 Evaluation.....................................110 AGRADECIMIENTOS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Contributors The Culture Box program was created by the University of New Mexico’s Latin American and Iberian Institute (LAII), with support provided by the LAII’s Title VI National Resource Center grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Contributing authors include Latin Americanist graduate students Adam Flores, Charla Henley, Jennie Grebb, Sarah Leister, Neoshia Roemer, Jacob Sandler, Kalyn Finnell, Lorraine Archibald, Amanda Hooker, Teresa Drenten, Marty Smith, María José Ramos, and Kathryn Peters. LAII project assistant Katrina Dillon created all curriculum materials. Project management, document design, and editorial support were provided by LAII staff person Keira Philipp-Schnurer. Amanda Wolfe, Marie McGhee, and Scott Sandlin generously collected and donated materials to the Culture Box of Cuba. Sponsors All program materials are readily available to educators in New Mexico courtesy of a partnership between the LAII, Instituto Cervantes of Albuquerque, National Hispanic Cultural Center, and Spanish Resource Center of Albuquerque - who, together, oversee the lending process. To learn more about the sponsor organizations, see their respective websites: • Latin American & Iberian Institute at the -

When Racial Inequalities Return: Assessing the Restratification of Cuban Society 60 Years After Revolution

When Racial Inequalities Return: Assessing the Restratification of Cuban Society 60 Years After Revolution Katrin Hansing Bert Hoffmann ABSTRACT Few political transformations have attacked social inequalities more thoroughly than the 1959 Cuban Revolution. As the survey data in this article show, however, sixty years on, structural inequalities are returning that echo the prerevolutionary socioethnic hierarchies. While official Cuban statistics are mute about social differ- ences along racial lines, the authors were able to conduct a unique, nationwide survey with more than one thousand respondents that shows the contrary. Amid depressed wages in the state-run economy, access to hard currency has become key. However, racialized migration patterns of the past make for highly unequal access to family remittances, and the gradual opening of private business disfavors Afro- Cubans, due to their lack of access to prerevolutionary property and startup capital. Despite the political continuity of Communist Party rule, a restructuring of Cuban society with a profound racial bias is turning back one of the proudest achieve- ments of the revolution. Keywords: Cuba, social inequality, race, socialism, migration, remittances he 1959 Cuban Revolution radically broke with a past in which “class” tended Tto influence and overlap most aspects of social life, including “race,” gender, income, education, and territory. The “centralized, state-sponsored economy, which provided full employment and guaranteed modest income differences, was the great social elevator of the lower strata of society. As a result, by the 1980s Cuba had become one of the most egalitarian societies in the world” (Mesa-Lago and Pérez- López 2005, 71). Katrin Hansing is an associate professor of sociology and anthropology at Baruch College, City University of New York. -

Cuba! Identity Revealed Through Cultural Connections

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2016 Volume II: Literature and Identity Cuba! Identity Revealed through Cultural Connections Curriculum Unit 16.02.07 by Waltrina Dianne Kirkland-Mullins Introduction I am a New Haven, Connecticut Public School instructor who loves to travel abroad. I do so because it affords me the opportunity to connect with people from myriad cultures, providing insight into the lives, customs, and traditions of diverse populations within our global community. It too helps me have a better understanding of diverse groups of Americans whose families live beyond American shores, many with whom I interact right within my New Haven residential and school community. Equally important, getting to experience diverse cultures first-hand helps to dispel misconceptions and false identification regarding specific cultural groups. Last summer, I was honored to travel to Cuba as part of a team of college students, teaching professionals, and businesspersons who visited the country with Washington State’s Pinchot University. While there, I met and conversed with professors, educators, entrepreneurs, scientists, and everyday folk—gaining insight into Cuba and its people from their perspective. Through that interaction, I experienced that Cuba, like the U.S., is a diverse nation. Primarily comprised of descendants of the Taíno, the Ciboney, and Arawak (original inhabitants of the island), Africans, and Spaniards, the diversity is evident in the color spectrum of the population, ranging from deep, ebony-hues to sun-kissed tan and creamy vanilla tones. I too learned something deeper. One afternoon, my Pinchot roommate and I decided to venture out to visit Callejon de Hamel , a narrow thoroughfare laden with impressive Santeria murals, sculptures, and Yoruba images. -

Cuba in Transition

CUBA: BANKING REFORMS, THE MONETARY GUIDELINES OF THE SIXTH PARTY CONGRESS, AND WHAT NEEDS TO BE DONE Lorenzo L. Pérez1 By the advent of the revolutionary government in The first section of this paper discusses the current 1959, Cuba had a dynamic banking sector, with a banking and monetary situation in Cuba, including a growing domestically-owned bank sector and foreign discussion on the existence of dual currencies and owned banks which had operated in Cuba for several multiple exchange rates. The second section analyzes decades. The Cuban National Bank, the central the monetary, credit, and exchange rate guidelines of bank, had been established in the early 1950s. The the Sixth Party Congress in the light of Cuba’s bank- ing problems. The last section provides policy recom- revolutionary government nationalized the banks in mendations to modernize and develop the banking October 1960, and eventually most commercial and sector in Cuba based on international best practices. central bank activities were, following the model of the Soviet Union, concentrated in the Cuban Na- CURRENT BANKING SYSTEM tional Bank and a few state banks until the banking After the nationalization of the banks but before the reforms implemented in the mid-1990s.2 In May reforms of the 1990s, there existed in Cuba, in addi- 1997, two important banking laws were passed, tion to the National Bank, a savings bank, the Banco which created a new institution for central bank Popular de Ahorro (BPA), created in 1983 as the functions, the Central Bank of Cuba, and provided a only retail-oriented depository institution, and the Banco Financiero Internacional (BFI), created in broader basis to create state-owned commercial 1984 to finance international commerce. -

Black Market Peso Exchange As a Mechanism to Place Substantial Amounts of Currency from U.S

United States Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network FinCEN Advisory Subject: This advisory is provided to alert banks and other depository institutions Colombian to a large-scale, complex money laundering system being used extensively by Black Market Colombian drug cartels to launder the proceeds of narcotics sales. This Peso Exchange system is affecting both U.S. financial depository institutions and many U.S. businesses. The information contained in this advisory is intended to help explain how this money laundering system works so that U.S. financial institutions and businesses can take steps to help law enforcement counter it. Overview Date: November Drug sales in the United States are estimated by the Office of National 1997 Drug Control Policy to generate $57.3 billion annually, and most of these transactions are in cash. Through concerted efforts by the Congress and the Executive branch, laws and regulatory actions have made the movement of this cash a significant problem for the drug cartels. America’s banks have effective systems to report large cash transactions and report suspicious or Advisory: unusual activity to appropriate authorities. As a result of these successes, the Issue 9 placement of large amounts of cash into U.S. financial institutions has created vulnerabilities for the drug organizations and cartels. Efforts to avoid report- ing requirements by structuring transactions at levels well below the $10,000 limit or camouflage the proceeds in otherwise legitimate activity are continu- ing. Drug cartels are also being forced to devise creative ways to smuggle the cash out of the country. This advisory discusses a primary money laundering system used by Colombian drug cartels. -

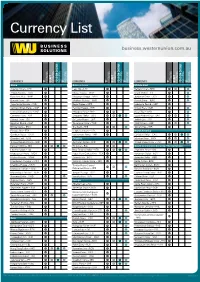

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar –