Cooperation and Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scotland the Brave? an Overview of the Impact of Scottish Independence on Business

SCOTLAND THE BRAVE? AN OVERVIEW OF THE IMPACT OF SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE ON BUSINESS JULY 2021 SCOTLAND THE BRAVE? AN OVERVIEW OF THE IMPACT OF SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE ON BUSINESS Scottish independence remains very much a live issue, as First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, continues to push for a second referendum, but the prospect of possible independence raises a host of legal issues. In this overview, we examine how Scotland might achieve independence; the effect of independence on Scotland's international status, laws, people and companies; what currency Scotland might use; the implications for tax, pensions and financial services; and the consequences if Scotland were to join the EU. The Treaty of Union between England of pro-independence MSPs to 72; more, (which included Wales) and Scotland even, than in 2011. provided that the two Kingdoms "shall upon the first day of May [1707] and Independence, should it happen, will forever after be United into one Kingdom affect anyone who does business in or by the Name of Great Britain." Forever is with Scotland. Scotland can be part of a long time. Similar provisions in the Irish the United Kingdom or it can be an treaty of 1800 have only survived for six independent country, but moving from out of the 32 Irish counties, and Scotland the former status to the latter is highly has already had one referendum on complex both for the Governments whether to dissolve the union. In that concerned and for everyone else. The vote, in 2014, the electorate of Scotland rest of the United Kingdom (rUK) could decided by 55% to 45% to remain within not ignore Scotland's democratic will, but the union, but Brexit and the electoral nor could Scotland dictate the terms on success of the SNP mean that Scottish which it seceded from the union. -

Issues Around Scottish Independence

Issues Around Scottish Independence by David Sinclair September 1999 Published by The Constitution Unit 29/30 Tavistock Square London WC 1H 9EZ Tel. 017 1 504 4977 O The Constitution Unit 1999 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE The referendum: who votes, and who decides the question? When should a referendum be held? Speed of the transition Who negotiates for each side? SCOTLAND IN THE WORLD ECONOMICS OF INDEPENDENCE SCOTLAND AND THE REST OF THE UK ANNEX 1: GREENLAND AND SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE ANNEX 2: THE BACKGROUND TO THE ARGUMENTS OVER SCOTLAND'S FISCAL DEFICIT Expenditure Revenue Conclusions Executive Summary The debate about Scottish independence should include not only the case for and against independence but a better understanding of the process of independence itself. There are a number of key issues which would need to be resolved before Scotland could become independent. 1. If the issue of independence is put to a referendum who should vote in that referendum and what should the question be? Should that referendum be held before or after negotiations on independence? 2. Once negotiations are taking place, how quickly can a transition to be independence be achieved? 3. What are the key issues that will need to be negotiated? Can any likely sticking points be identified? 4. What would the position of an independent Scotland be in international law? Would Scotland automatically succeed to UK treaty rights and obligations, including membership of the EU? Or would these have to be renegotiated? 5. What are the economics of an independent Scotland? Answering this question involves understanding the current financial position of Scotland within the UK, the likely future finances of Scotland as an independent country, and the costs of transition to independence. -

Download the Scotland Ebook

Yes or No? A collection of writing on Scottish independence Neal Ascherson, Menzies Campbell, David Marquand, Linda Colley, John Kay, John Kerr PROSPECT 2014 2 Introduction he vision of an independent Scotland will not disap- articulate a compelling case for the Union other than one based pear, even with a No vote in the referendum on 18th on prophesies of doom for Scotland if it goes it alone. This is September, which opinion polls suggest is likely. As partly because the question that David Cameron chose to pose Neal Ascherson argues in “Why I’ll vote Yes,” that in this referendum—full independence, or no change at all—is idea, now that it has taken root, will not go away. the wrong one. There should have been the option on the bal- TWhen Scots looks south, Ascherson writes, they see little of lot of “devo-max”—full autonomy, minus responsibility for for- themselves there. And all the while, the internal voice which eign policy and defence. Yet Cameron ducked that, wanting muses that “my country was independent once” gets louder. to force Scotland into a No vote; even though that is the likely Like many countries before it, Scotland sees independence “as result, the tactic has backfired by forcing serious consideration the way to join the world, modernise and take responsibility for of the Yes option. their own actions and mistakes.” Whatever happens on 18th September, Britain will have to Yet for all the feelings of national identity and self-assertion rethink the way it runs itself. The writer and former Labour MP that the referendum campaign has stirred up, economic ques- David Marquand imagines a federal future for the UK which tions—particularly concerning the currency and membership of grants autonomy to the constituent parts of the Union, short the of European Union—have dominated the debate. -

Scottish Nationalism

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Summer 2012 Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination Brian Duncan James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Duncan, Brian, "Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination" (2012). Masters Theses. 192. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scottish Nationalism: The Symbols of Scottish Distinctiveness and the 700 Year Continuum of the Scots’ Desire for Self Determination Brian Duncan A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History August 2012 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….…….iii Chapter 1, Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 2, Theoretical Discussion of Nationalism………………………………………11 Chapter 3, Early Examples of Scottish Nationalism……………………………………..22 Chapter 4, Post-Medieval Examples of Scottish Nationalism…………………………...44 Chapter 5, Scottish Nationalism Masked Under Economic Prosperity and British Nationalism…...………………………………………………….………….…………...68 Chapter 6, Conclusion……………………………………………………………………81 ii Abstract With the modern events concerning nationalism in Scotland, it is worth asking how Scottish nationalism was formed. Many proponents of the leading Modernist theory of nationalism would suggest that nationalism could not have existed before the late eighteenth century, or without the rise of modern phenomena like industrialization and globalization. -

National Identity Construction During the Referendum Campaign for Scottish Independence 2014

National Identity Construction During the Referendum campaign for Scottish Independence 2014. A Critical Discourse Analysis Asha Manikiza 861123T369 International migration and Ethnic Relations One-year Master Thesis (IM627L) Spring semester 2018 Supervisor: Anne Sofie Roald Word Count: 15,888 Abstract Scotland is one of the four nations that make up the plurinational UK. It is as of yet the only one of these nations to have a referendum on its independence. Using Critical Discourse Analysis of 20 newspaper articles at different times in the referendum campaign, I have seen how Scottish national identity has been constructed. The study reveals that far from constructing a national identity based on culture, symbols or historic myth, the Scots base their identity largely on a differing approach to economic policy than the English. Keywords: Scotland, Critical Discourse Analysis, Newspapers, National identity construction, Referendum Contents Page Abstract Table of Contents Abbreviations 1. Introduction 1 1.2 Aim and Research question 1 1.3 Delimitations 2 1.4 Research Relevance 2 1.5 Terminalogical Explannations 2 1.6 Thesis Structure 3 2. Contextual Background 4 2.1 The Scottish Question: A historical Overview 4 2.2 Why Focus on Scotland? 4 2.3 Why the Increase In Scottish Nationalism? 5 2.4 Why Focus on the Referendum Campaign for Scottish Independence 2014? 5 2.5 Role of the Newspapers in national identity construction 6 3. Previous Research 7 3.1 The Shifting Concept of a Scottish National Identity and Britishness 7 3.2 The Crisis of Union and the move towards Independence 8 4. Theoretical Framework 10 4.1 Banal Nationalism 10 4.2 Imagined Communities 11 5. -

LSE Brexit: Welsh Independence: Can Brexit Awaken the Sleeping Dragon? Page 1 of 4

LSE Brexit: Welsh independence: can Brexit awaken the sleeping dragon? Page 1 of 4 Welsh independence: can Brexit awaken the sleeping dragon? Wales is the only devolved nation within the UK that has never caused a stir in constitutional terms. This is because Welsh independence has remained largely a dormant political issue, both within Wales and within the wider UK context. Can Brexit awaken the sleeping dragon, asks Darryn Nyatanga (University of Liverpool)? Brexit does present the opportunity to awaken real discussion on the potential of Welsh Independence. This can be attributed to two reasons, firstly – independence could be the only way to ensure Welsh interests are met after Brexit. Also, there has been a growth in sub-state nationalism within the UK, exposed by the Brexit referendum and the withdrawal process, highlighting the point that the UK is united in name only. Welsh nationalism The agenda for Welsh independence can only arguably be pushed by a strong sense of nationalism. This is the case in both Scotland and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, nationalism has been spearheaded by the SNP. Scottish independence (and Scottish home rule – before the introduction of devolution in 1998) has long been the main objective for the SNP since its genesis. In the case of Northern Ireland, two main forms of national identity exist; British and Irish. The latter identity challenges the status quo of the UK’s unitary nature. Irish nationalism in political terms is spearheaded by Sinn Fein, who advocate for the constitutional status of Northern Ireland to change i.e. Irish (re)unification. -

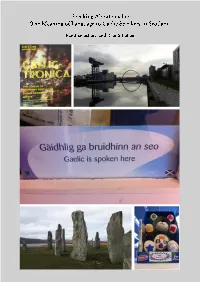

Speaking About Gaelic: the Meaning of Language to Gaelic Speakers in Scotland

Speaking About Gaelic: The Meaning of Language to Gaelic Speakers in Scotland Matthias Schmal and Roos Scholten Speaking About Gaelic: The meaning of language to Gaelic Speakers in Scotland Bachelor thesis 2015-2016 Matthias Schmal 3798526 [email protected] Roos Scholten 4006127 [email protected] June 24, 2016 Coordinator: Jesse Jonkman Wordcount: 20 940 4 Speaking About Gaelic: The meaning of Language to Gaelic speakers in Scotland 5 Matthias Schmal and Roos Scholten Contents Map of Scotland 7 Acknowledgements 9 Introduction 10 1. Theoretical framework 13 Introduction 13 1.1. Identity 13 1.2. Traditions and history in national imagination 15 1.3. Language makes the community 16 1.4. Abstract systems and the risks of a globalizing world 18 2. Gaelic speakers and Scottish nationalism 21 Introduction 21 2.1. Scottish nationalism 21 2.2. Gaelic as an invented tradition 21 2.3. Gaelic Medium Education and the Gaelic revival 22 2.4. Research locations 24 3. Gaelic in the ‘Homeland’ of the language 25 Introduction 25 3.1. An island community 25 3.2. Speaking and imagining Gaelic 27 3.2.1. Country pumpkins and worlds of opportunities 28 3.2.2. Language use as a reflection of its status 29 3.3. Incomers and island traditions 29 3.3.1. The importance of tradition 30 3.3.2. Distinguishing national and local ways of identification 30 3.4. Language planning and the island perspective 32 3.4.1. A focus on education 32 3.4.2. Modernization of the language 33 4. -

Scotland: Devolution and the Legal Implications of Scottish Independence

Scotland: Devolution and the legal implications of Scottish independence Devolution gives Scotland the best of both worlds. It means decisions on issues like childcare, health and education can be made in Scotland, but that Scotland also benefits from being part of a larger UK with economic strength, national security and international influence. In the event of independence, Scotland would leave the UK to form an entirely new state. This would involve setting up all its own domestic institutions and applying to any international organisations it wished to join. The rest of the UK would continue as before. The UK’s institutions and membership of organisations would all remain. www.gov.uk/scotlandanalysis Devolution offers Scotland the best of both worlds The Scottish Parliament has the power to take decisions on issues like health, education and policing, to address Scottish needs. For example, to deal with high smoking rates in Scotland, which contributed to 13,000 deaths a year, the Scottish Parliament was the first in the UK to ban smoking in public places. Devolution means that people in Scotland benefit from decisions that are best made on a UK-wide basis in areas like defence, security, and foreign and economic policy. For example, by pooling resources the UK was able to inject £45.5 billion into RBS to protect the financial system and savers deposits in the 2008 financial crisis. Devolution is a flexible and evolving system of government. The Scotland Act 2012 contained the biggest devolution of financial powers to Scotland since 1707. From 2016, the Scottish Government will have £2.2 billion of borrowing powers and will set a Scottish rate of income tax, making it responsible for raising around a third of the money it spends. -

The Scottish Independence Referendum and After

THE SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE REFERENDUM AND AFTER Michael Keating Professor of Politics at the University of Aberdeen, and director of the Centre on Constitutional Change SUMMARY: The Scottish Dilemma. – Constitutional Traditions in Scotland. – The Na- tionalists in Government. – The Battle Ground. – Economy and Finance. – Welfare. – Defence and Security. – Europe. – The Campaign. – The Outcome. – The Aftermath. – The Smith Report. – EVEL and Barnett. – The European Context. – The Future of the State. – Abstract – Resum – Resumen. The Scottish Dilemma The Scottish independence referendum on 18 September 2014 was a highly unusual event, an agreed popular vote on secession in an advanced industrial democracy. The result, with 45 per cent for in- dependence and 55 per cent against, might seem to have settled the question decisively. Yet, paradoxically, it is the losing side that has emerged in better shape and more optimistic, while the winners have been plunged into difficulties. In order to understand what has hap- pened, we need to examine the referendum in light of the evolution of the United Kingdom and the changing place of Scotland within it. Scotland should be seen as a case of the kind of spatial rescaling that is taking place more generally across Europe, as new forms of state- hood and of sovereignty evolve. Scottish public opinion favours more self-government but no longer recognizes the traditional nation-state model presented in the referendum question. Article received 12/12/2014; approved 12/12/2014. 73 REAF núm. 21, abril 2015, p. 73-98 Michael Keating Constitutional Traditions in Scotland Since the late nineteenth century union, there have been three main constitutional traditions in Scotland. -

The Quest for an Independent Scotland: the Impact of Culture, Economics, and International Relations Theory on Votes of Self-Det

The Journal of Economics and Politics Volume 25 Issue 1 Article 2 2020 The Quest for an Independent Scotland: The Impact of Culture, Economics, and International Relations Theory on Votes of Self- Determination Sam Rohrer University of North Georgia, [email protected] James Gilley Nicholls State University, [email protected] Nathan Price University of North Georgia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/jep Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rohrer, Sam; Gilley, James; and Price, Nathan (2020) "The Quest for an Independent Scotland: The Impact of Culture, Economics, and International Relations Theory on Votes of Self-Determination," The Journal of Economics and Politics: Vol. 25 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://collected.jcu.edu/jep/vol25/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Economics and Politics by an authorized editor of Carroll Collected. Rohrer et al.: The Quest for an Independent Scotland Introduction Scotland and England have always had an at best tenuous relationship with one another. Though they have been united for over 300 years, this union did not emerge without conflict. In the ensuing centuries, a new common British identity was formed, one centered around the growth of empire. Yet the politics, economics and culture of these two nations have remained distinct. In the decades following the end of the Collectivist Consensus, these differences have become ever more pronounced, leading to calls for renewed Scottish independence. -

Putting Scotland's Future in Scotland's Hands

Scotland’s Right to Choose Putting Scotland’s Future in Scotland’s Hands What if that other voice we all know so well responds by saying, 'We say no, and we are the state'? Well we say yes – and we are the people. Canon Kenyon Wright Putting Scotland’s Future in Scotland’s Hands Introduction by the First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon First Minister of Scotland The Scottish Government believes the best future for Scotland is to be an independent country in order to build a fairer, more prosperous society. It is a fundamental democratic principle that The Scottish Government is a strong advocate the decision on whether or not Scotland of the values of human dignity, freedom, becomes independent should rest with the democracy, equality, the rule of law, and people who live in Scotland. respect for human rights. There has been a significant and material We are therefore committed to an agreed, change in circumstances since the 2014 legal process which adheres to and celebrates referendum and therefore, in line with the those values, and which will be accepted as mandate received in the 2016 Holyrood legitimate in Scotland, the UK as a whole, and election, and reinforced in subsequent UK by the international community. general elections—most recently in December 2019—the Scottish Government believes Scotland is not a region questioning its place people in Scotland have the right to consider in a larger unitary state; we are a country in a their future once again. voluntary union of nations. Our friends in the rest of the UK will always be our closest allies The decision on whether a new referendum and neighbours but in line with the principle of should be held, and when, is for the Scottish self-determination, people in Scotland have the Parliament to make – not a Westminster right to determine whether the time has come government which has been rejected by the for a new, better relationship, in which we can people of Scotland. -

Scottish Independence Referendum: Legal Issues

By David Torrance 30 July 2021 Scottish independence referendum: legal issues 1 Summary 2 A short history of the Union 3 Scotland Act 1998 4 Referendum proposals, 1999-2010 5 Referendum negotiations, 2012-14 6 Referendum developments, 2016-21 7 Legislative process and role of the Supreme Court commonslibrary.parliament.uk Number CBP9104 Scottish independence referendum: legal issues Disclaimer The Commons Library does not intend the information in our research publications and briefings to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. We have published it to support the work of MPs. You should not rely upon it as legal or professional advice, or as a substitute for it. We do not accept any liability whatsoever for any errors, omissions or misstatements contained herein. You should consult a suitably qualified professional if you require specific advice or information. Read our briefing ‘Legal help: where to go and how to pay’ for further information about sources of legal advice and help. This information is provided subject to the conditions of the Open Parliament Licence. Feedback Every effort is made to ensure that the information contained in these publicly available briefings is correct at the time of publication. Readers should be aware however that briefings are not necessarily updated to reflect subsequent changes. If you have any comments on our briefings please email [email protected]. Please note that authors are not always able to engage in discussions with members of the public who express opinions about the content of our research, although we will carefully consider and correct any factual errors.