The Afroasiatic Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Langues Et Cultures Dans Le Bassin Du Lac Tchad

LANGUES ET CULTURES DANS LE BASSIN DU LAC TCHAD Journées dëtudes les 4 et 5 septembre 1984 ORSTOM (Paris) TEXTES RASSEMBLES ET PRESENTES par Daniel BARRETEAU LANGUES ET CULTURES DANS LE BASSIN DU LAC TCHAD Journées d’études les 4 et 5 septembre 1984 ORSTOM (Paris) LANGUES ET CULTURES DANS LE BASSIN DU LAC TCHAD Journées dëtudes les 4 et 5 septembre 1984 ORSTOM (Paris) Éditions de I’ORSTOM INSTITUT FRANÇAIS DE RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE POUR LE DÉVELOPPEMENT EN COOPÉRATION Collection COLLOQUES et SÉMINAIRES PARIS 1987 .-.. .* Remerciements sincères a tous les auteurs et collaborateurs. Dactylographie et maquettage : Daniel BARRETEAU Liliane SORIN-BARRETEAU Cartographie : Roland BRETON Illustrations : Dessins de Danièle MOLEZ, d'aprk des photographies de Guy MAURETTE La loi du 11 mars 1957 n’autorisant, aux termes des alinéas 2 et 3 de l’article 41, d’une part, que les tcopies ou reproductions strictement rbervbes B l’usage privb du copiste et non destinbes A une utilisa- tion collectiver et, d’autre part, que les analyses et les courtes citations dans un but d’exemple et d’illus- tration, (toute reprbentation ou reproduction intbgrale, ou partielle, faite sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayants droit ou ayants cause, est illicites (elinbe 1” de l’article 40). Cette reprbentation ou reproduction, par quelque procbdb que ce soit, constituerait donc une contrefa- con sanctionnbe par les articles 426 et suivants du Code Pbal. I66N : 0767-2896 (DORSTOfvllS87 ISBN : 2-7099-0890-5 . SOMMAIRE page INTRODUCTION GENERALE ET RESUMES . 9-19 COMPARAISON ET CLASSIFICATION LINGUISTIQUES . 21-77 E. WOLFF: Introductory remarks on the linguistic si- tuation in the Lake Chad Basin and the study of language contact . -

Grammatical Gender in Hindukush Languages

Grammatical gender in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Julia Lautin Department of Linguistics Independent Project for the Degree of Bachelor 15 HEC General linguistics Bachelor's programme in Linguistics Spring term 2016 Supervisor: Henrik Liljegren Examinator: Bernhard Wälchli Expert reviewer: Emil Perder Project affiliation: “Language contact and relatedness in the Hindukush Region,” a research project supported by the Swedish Research Council (421-2014-631) Grammatical gender in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Julia Lautin Abstract In the mountainous area of the Greater Hindukush in northern Pakistan, north-western Afghanistan and Kashmir, some fifty languages from six different genera are spoken. The languages are at the same time innovative and archaic, and are of great interest for areal-typological research. This study investigates grammatical gender in a 12-language sample in the area from an areal-typological perspective. The results show some intriguing features, including unexpected loss of gender, languages that have developed a gender system based on the semantic category of animacy, and languages where this animacy distinction is present parallel to the inherited gender system based on a masculine/feminine distinction found in many Indo-Aryan languages. Keywords Grammatical gender, areal-typology, Hindukush, animacy, nominal categories Grammatiskt genus i Hindukush-språk En areal-typologisk studie Julia Lautin Sammanfattning I den här studien undersöks grammatiskt genus i ett antal språk som talas i ett bergsområde beläget i norra Pakistan, nordvästra Afghanistan och Kashmir. I området, här kallat Greater Hindukush, talas omkring 50 olika språk från sex olika språkfamiljer. Det stora antalet språk tillsammans med den otillgängliga terrängen har gjort att språken är arkaiska i vissa hänseenden och innovativa i andra, vilket gör det till ett intressant område för arealtypologisk forskning. -

Central Chadic Reconstructions

Central Chadic Reconstructions Richard Gravina 2014 © 2014 Richard Gravina Foreword This document is a presentation of a reconstruction of the Proto-Central Chadic lexicon, along with full supporting data. These reconstructions are presented in conjunction with my PhD dissertation on the reconstruction of the phonology of Proto-Central Chadic (University of Leiden). You can view the data at http://centralchadic.webonary.org, and also view a summary dictionary of Proto- Central Chadic at http://protocentralchadic.webonary.org. The Central Chadic languages are spoken in north-east Nigeria, northern Cameroon, and western Chad. The Ethnologue lists 79 Central Chadic languages. Data comes from 59 of these languages, along with a number of dialects. Classification The classification used here results from the identification of regular changes in the consonantal phonemes amongst groups of Central Chadic languages. Full evidence is given in the dissertation. The summary classification is as follows (dialects are in parentheses; languages not cited in the data are in italics): Bata group: Bachama, Bata, Fali, Gude, Gudu, Holma, Jimi, Ngwaba, Nzanyi, Sharwa, Tsuvan, Zizilivakan Daba group: Buwal, Daba, Gavar, Mazagway, Mbudum, Mina Mafa group: Cuvok, Mafa, Mefele Tera group: Boga, Ga’anda, Hwana, Jara, Tera (Nyimatli) Sukur group: Sukur Hurza group: Mbuko, Vame Margi group: Bura, Cibak, Kilba, Kofa, Margi, Margi South, Nggwahyi, Putai Mandara group: Cineni, Dghwede, Glavda, Guduf, Gvoko, Mandara (Malgwa), Matal, Podoko Mofu group: Dugwor, Mada, -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

A Comparative Phonetic Study of the Circassian Languages Author(S

A comparative phonetic study of the Circassian languages Author(s): Ayla Applebaum and Matthew Gordon Proceedings of the 37th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: Special Session on Languages of the Caucasus (2013), pp. 3-17 Editors: Chundra Cathcart, Shinae Kang, and Clare S. Sandy Please contact BLS regarding any further use of this work. BLS retains copyright for both print and screen forms of the publication. BLS may be contacted via http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/bls/. The Annual Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society is published online via eLanguage, the Linguistic Society of America's digital publishing platform. A Comparative Phonetic Study of the Circassian Languages1 AYLA APPLEBAUM and MATTHEW GORDON University of California, Santa Barbara Introduction This paper presents results of a phonetic study of Circassian languages. Three phonetic properties were targeted for investigation: voice-onset time for stop consonants, spectral properties of the coronal fricatives, and formant values for vowels. Circassian is a branch of the Northwest Caucasian language family, which also includes Abhaz-Abaza and Ubykh. Circassian is divided into two dialectal subgroups: West Circassian (commonly known as Adyghe), and East Circassian (also known as Kabardian). The West Circassian subgroup includes Temirgoy, Abzekh, Hatkoy, Shapsugh, and Bzhedugh. East Circassian comprises Kabardian and Besleney. The Circassian languages are indigenous to the area between the Caspian and Black Seas but, since the Russian invasion of the Caucasus region in the middle of the 19th century, the majority of Circassians now live in diaspora communities, most prevalently in Turkey but also in smaller outposts throughout the Middle East and the United States. -

Gurage) Morphology∗

Chaha (Gurage) Morphology∗ Sharon Rose University of California, San Diego 1. Introduction Chaha (cha) is a Gurage dialect belonging to the Ethiopian branch of the Semitic language family. It is a member of the Western Gurage group of dialects along with Ezha, Gyeta, Endegegn and Inor. Chaha itself also has some sub-dialects, Gura and Gumer. The data for this article come from the dialect spoken in the main Chaha town of Endeber and neighboring villages, such as Yeseme. Endeber is located approximately 180 kilometers south-west of Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. The 1994 census ∗ Many thanks to Hailu Yacob and Tadesse Sefer for contributing data, and to Alan Kaye for editorial assistance. I am extremely grateful to Degif Petros Banksira for extensive comments on the article, leading to significant improvements. Errors are my responsibility. The following abbreviations are used: acc. = accusative; f = feminine; m = masculine; p = plural; s = singular; impf. = imperfect; pf. = perfect; juss. = jussive; conv. = converb; inf. = infinitive; impl. = impersonal; caus. = causative; neg. = negative; def.fut. = definite future; indef.fut. = indefinite future; O = object. Person, gender and number combinations such as 3fs correspond to subject marking unless otherwise indicated. Symbols are in accordance with IPA except for the palatal affricates, for which I use [c] and [j]. Note that the vowel I transcribe as [] is other authors’ (Leslau, Hetzron) [ä] and my [] is their []. 1 divides the Gurage into three groups according to language: Soddo, Silte and Sebat Bet. Sebat Bet translates as ‘seven houses’ and is a linguistic-cultural term referring to the seven main groups of the Western Gurage. -

Aree Di Transizione Linguistiche E Culturali in Africa 3 Impaginazione Gabriella Clabot

ATrA Aree di transizione linguistiche e culturali in Africa 3 Impaginazione Gabriella Clabot © copyright Edizioni Università di Trieste, Trieste 2017. Proprietà letteraria riservata. I diritti di traduzione, memorizzazione elettronica, di riproduzione e di adattamento totale e parziale di questa pubblicazione, con qualsiasi mezzo (compresi i microfilm, le fotocopie e altro) sono riservati per tutti i paesi. ISBN 978-88-8303-821-1 (print) ISBN 978-88-8303-822-8 (online) EUT Edizioni Università di Trieste via Weiss 21 – 34128 Trieste http://eut.units.it https://www.facebook.com/EUTEdizioniUniversitaTrieste Cultural and Linguistic Transition explored Proceedings of the ATrA closing workshop Trieste, May 25-26, 2016 Ilaria Micheli (ed.) EUT EDIZIONI UNIVERSITÀ DI TRIESTE Table of contents Ilaria Micheli Shereen El Kabbani & Essam VII Introduction Elsaeed 46 The Documentation of the Pilgrimage Arts in Upper Egypt – A comparative PART I – ANTHROPOLOGY / Study between Ancient and Islamic Egypt CULTURE STUDIES Signe Lise Howell PART II – ARCHAEOLOGY 2 Cause: a category of the human mind? Some social consequences of Chewong Paul J. Lane (Malaysian rainforest hunter-gatherers) 60 People, Pots, Words and Genes: ontological understanding Multiple sources and recon-structions of the transition to food production Ilaria Micheli in eastern Africa 13 Women's lives: childhood, adolescence, marriage and motherhood among Ilaria Incordino the Ogiek of Mariashoni (Kenya) and 78 The analysis of determinatives the Kulango of Nassian (Ivory Coast) of Egyptian -

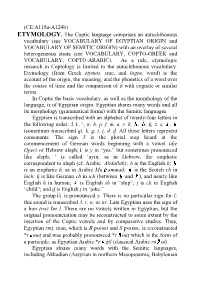

ETYMOLOGY. the Coptic Language Comprises an Autochthonous

(CE:A118a-A124b) ETYMOLOGY. The Coptic language comprises an autochthonous vocabulary (see VOCABULARY OF EGYPTIAN ORIGIN and VOCABULARY OF SEMITIC ORIGIN) with an overlay of several heterogeneous strata (see VOCABULARY, COPTO-GREEK and VOCABULARY, COPTO-ARABIC). As a rule, etymologic research in Coptology is limited to the autochthonous vocabulary. Etymology (from Greek etymos, true, and logos, word) is the account of the origin, the meaning, and the phonetics of a word over the course of time and the comparison of it with cognate or similar terms. In Coptic the basic vocabulary, as well as the morphology of the language, is of Egyptian origin. Egyptian shares many words and all its morphology (grammatical forms) with the Semitic languages. Egyptian is transcribed with an alphabet of twenty-four letters in the following order: 3, „ , ‘, w, b, p, f, m, n, r, h, , , h, z, s, , (sometimes transcribed q), k, g, t, t, d, d. All these letters represent consonants. The sign 3 is the glottal stop heard at the commencement of German words beginning with a vowel (die Oper) or Hebrew aleph; „ is y in “yes,” but sometimes pronounced like aleph; ‘ is called ‘ayin, as in Hebrew, the emphatic correspondent to aleph (cf. Arabic ‘Abdallah); h is the English h; is an emphatic h, as in Arabic Mu ammad; is the Scotch ch in loch; h is like German ch in ich (between and ), and nearly like English h in human; is English sh in “ship”; t is ch in English “child”; and d is English j in ‘joke.” The group „„ is pronounced y. -

Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic

UC Santa Cruz Phonology at Santa Cruz, Volume 7 Title Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0765s94q Author Kramer, Ruth Publication Date 2018-04-10 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic ∗∗∗ Ruth Kramer 1. Introduction One of the most distinctive features of many Afroasiatic languages is nonconcatenative morphology. Instead of attaching an affix directly before or after a root, languages like Modern Hebrew interleave an affix within the segments of a root. An example is in (1). (1) Modern Hebrew gadal ‘he grew’ gidel ‘he raised’ gudal ‘he was raised’ In the mini-paradigm in (1), the discontinuous affixes /a a/, /i e/, and /u a/ are systematically interleaved between the root consonants /g d l/ to indicate perfective aspect, causation and voice, respectively. The consonantal root /g d l/ ‘big’ never surfaces on its own in the language: it must be inflected with some vocalic affix. Additional Afroasiatic languages with nonconcatenative morphology include other Semitic languages like Arabic (McCarthy 1979, 1981; McCarthy and Prince 1990), many Ethiopian Semitic languages (Rose 1997, 2003), and Modern Aramaic (Hoberman 1989), as well as non-Semitic languages like Berber (Dell and Elmedlaoui 1992, Idrissi 2000) and Egyptian (also known as Ancient Egyptian, the autochthonous language of Egypt; Gardiner 1957, Reintges 1994). The nonconcatenative morphology of Afroasiatic languages has come to be known as root and pattern -

The Similarity and Mutual Intelligibility Between Amharic and Tigrigna Varieties

The Similarity and Mutual Intelligibility between Amharic and Tigrigna Varieties Tekabe Legesse Feleke Verona Univerisity Verona, Italy [email protected] Abstract without major difficulties (Demeke, 2001; Gutt, 1980). However, the similarity among the lan- The present study has examined the sim- guages is often obscured by the attitude of the ilarity and the mutual intelligibility be- speakers since language is considered as a sym- tween Amharic and two Tigrigna vari- bol of identity (Lanza and Woldemariam, 2008; ties using three tools; namely Levenshtein Smith, 2008). Hence, there are cases where vari- distance, intelligibility test and question- eties of the same languages are considered as dif- naires. The study has shown that both ferent languages (Hetzron, 1972; Hetzron, 1977; Tigrigna varieties have almost equal pho- Hudson, 2013; Smith, 2008). Therefore, due to netic and lexical distances from Amharic. politics, sensitivity to ethnicity and the lack of The study also indicated that Amharic commitment from the scholars, the exact number speakers understand less than 50% of the of languages in Ethiopia is not known (Bender and two varieties. Furthermore, the study Cooper, 1976; Demeke, 2001; Leslau, 1969).Fur- showed that Amharic speakers are more thermore, except some studies for example, Gutt positive about the Ethiopian Tigrigna va- (1980) and Ahland (2003) cited in Hudson (2013) riety than the Eritrean variety. However, on the Gurage varieties, and Bender and Cooper their attitude towards the two varieties (1971) on mutual intelligibility of Sidamo dialects, does not have an impact on their intelli- the degree of mutual intelligibility among various gibility. The Amharic speakers’ familiar- varieties and the attitude of the speakers towards ity to the Tigrigna varieties seems largely each others’ varieties has not been thoroughly in- dependent on the genealogical relation be- vestigated. -

Élémentsde Description Du Langi Langue Bantu F.33 De Tanzanie

ÉLÉMENTS DE DESCRIPTION DU LANGI LANGUE BANTU F.33 DE TANZANIE MARGARET DUNHAM Remerciements Je remercie très chaleureusement tous les Valangi, ce sont eux qui ont fourni la matière sur laquelle se fonde cet ouvrage, et notamment : Saidi Ikaji, Maryfrider Joseph, Mama Luci, Yuda, Pascali et Agnès Daudi, Gaitani et Philomena Paoli, M. Sabasi, et toute la famille Ningah : Ally, Saidi, Amina, Jamila, Nasri, Saada et Mei. Je remercie également mes autres amis de Kondoa : Elly Benson, à qui je dois la liste des noms d’arbres qui se trouve en annexe, et Elise Pinners, qui m’a logée à Kondoa et ailleurs. Je remercie le SNV et le HADO à Kondoa pour avoir mis à ma disposition leurs moyens de transport et leur bibliothèque. Je remercie les membres du LACITO du CNRS, tout le groupe Langue-Culture- Environnement et ceux qui ont dirigé le laboratoire pendant ma thèse : Jean-Claude Rivierre, Martine Mazaudon et Zlatka Guentchéva Je remercie tout le groupe bantu : Gladys Guarisma, Raphaël Kaboré, Jacqueline Leroy, Christiane Paulian, Gérard Philippson, Marie-Françoise Rombi et Serge Sauvageot, pour leurs conseils et pour leurs oreilles. Je remercie Jacqueline Vaissière pour ses conseils et sa disponibilité. Je remercie Sophie Manus pour la traduction du swahili du rapport de l’Officier culturel de Kondoa. Je remercie Ewen Macmillan pour son hospitalité chaleureuse et répétée à Londres. Je remercie mes amis à Paris qui ont tant fait pour me rendre la vie agréable pendant ce travail. Je remercie Eric Agnesina pour son aide précieuse, matérielle et morale. Et enfin, je ne saurais jamais assez remercier Marie-Françoise Rombi, pour son amitié et pour son infinie patience. -

Proposal for Ethiopic Script Root Zone LGR

Proposal for Ethiopic Script Root Zone LGR LGR Version 2 Date: 2017-05-17 Document version:5.2 Authors: Ethiopic Script Generation Panel Contents 1 General Information/ Overview/ Abstract ........................................................................................ 3 2 Script for which the LGR is proposed ................................................................................................ 3 3 Background on Script and Principal Languages Using It .................................................................... 4 3.1 Local Languages Using the Script .............................................................................................. 4 3.2 Geographic Territories of the Language or the Language Map of Ethiopia ................................ 7 4 Overall Development Process and Methodology .............................................................................. 8 4.1 Sources Consulted to Determine the Repertoire....................................................................... 8 4.2 Team Composition and Diversity .............................................................................................. 9 4.3 Analysis of Code Point Repertoire .......................................................................................... 10 4.4 Analysis of Code Point Variants .............................................................................................. 11 5 Repertoire ....................................................................................................................................