The New Majority: Pedaling Towards Equity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2016 OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER of the FLORIDA BICYCLE ASSOCIATION, INC

Messenger Building a Bicycle-Friendly Florida Vol. 19, No. 3 • Summer 2016 OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE FLORIDA BICYCLE ASSOCIATION, INC. Fast Track 2015 Florida Bicycle Association Annual Awards to... Congratulations to our 2015 Florida Bicycle Association Annual Award recipients! Membership 2 (above) Tom Sharbaugh, Patty Sousa and Sanibel Celebration Bicycle Club President Diane Olsson. Off-Road Bike Club: SORBA Enforcement Agency: of Cycling 8-9 (above right) SORBA Orlando president Mark Orlando Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Leon accepts the award with City of Orlando SORBA (Southern Off-Road Bicycle Office, Major Alan Hill Blue Light Corner 10 Mayor Buddy Dyer at May’s Ride with the Mayor. Association) Orlando is one of the newest The Florida Department of and most up and coming off road bicycle Transportation 2015 Highway Safety Plan Ask Geo 11 Bike Club: Sanibel Bicycle Club clubs in Florida. This non-profit 501(c) outlines a pedestrian and bicycle safety In 2014, Sanibel Bicycle Club proposed (3) organization is working with state and program to which law enforcement is Touring Calendar 14 to the City of Sanibel that it apply for a local governments to establish a network key. The Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Tourist Development grant to support the of off road trails in Central Florida. Former Office (HCSO) Safety Afoot campaign development of a tourist-focused “Cycling president Mitchell Greenberg and current of high visibility pedestrian and bicycle on Sanibel” safety video. The City applied president Mark Leon are leading the way to enforcement (HVE) countermeasures is for the TDC grant, which was awarded improve the trail systems of Snow Hill in highlighted in this plan. -

Manchester District CTT Clubs Comparison Spreadsheet.Xlsx

FOR CONTACT DETAILS SEE: FEB 2020 https://www.cyclingtimetrials.org.uk/find-clubs Name Active End Date Sponsor Website https://www.facebook.com/groups/1731966067494 3C Payment Sports TRUE 31/12/2020 TRUE 20/ 3C Test Team TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE www.cheshirecyclingclub.co.uk ABC Centreville TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE http://www.centreville.org.uk/ Allterrain road club TRUE 31/12/2020 TRUE 0 Altrincham Ravens CC TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE http://www.altrinchamravens.org.uk/ Ashley Touring CC TRUE 31/12/2020 TRUE 0 Audlem Cycling Club TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE www.audlemcyclingclub.co.uk// Boot Out Breast Cancer Cycling Club TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE http://www.teambootoutbc.cc/ Buxton CC/Sett Valley Cycles TRUE 31/12/2020 TRUE http://www.buxtoncyclingclub.co.uk/ Cheshire Maverick Cycle Club TRUE 31/12/2020 TRUE http://www.cheshiremaverick.com/ Cheshire Roads Club TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE http://www.cheshireroadsclub.co.uk/ Congleton CC TRUE 31/12/2020 TRUE http:/www.congletoncyclingclub.org.uk/ Crewe Clarion Wheelers TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE http://www.creweclarionwheelers.org/ Dukinfield Cyclists' Club TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE http://www.dukinfieldcc.org/ Eat Plants Not Pigs CC TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE http://eatplantsnotpigs.org// Element Cycling Team TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE www.facebook.com/elementcyclingteam/ Glossop Kinder Velo Cycling Club TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE http://www.glossopkindervelo.co.uk/ Holcombe Harriers TRUE 31/12/2020 FALSE holcombeharriers.com FOR CONTACT DETAILS SEE: FEB 2020 https://www.cyclingtimetrials.org.uk/find-clubs Name Active End Date Sponsor -

Application: State College - Centre Region | 00305

Application: State College - Centre Region | 00305 Started at: 4/21/2016 11:04 AM - Finalized at: 8/16/2016 11:37 AM Round: Fall 2016 Page: BFC: Application Intro Question Answer Community Name: State College - Centre Region Has the community Yes applied to the Bicycle Friendly Community program before? If awarded, the following links will appear on your BFA Award Profile on the League's Connect Locally Map. Community Website: www.crcog.net (if applicable) Community’s Twitter URL: (if applicable) Community’s https://www.facebook.com/centreregionalplanning/ Facebook URL: (if applicable) Page: BFC: Contact Information Question Answer Applicant First Name Trish Applicant Last Name Meek Job Title Senior Transportation Planner Department Centre Regional Planning Agency Employer Centre Region COG Street Address (No 2643 Gateway Drive Suite 4 PO Box, please) City State College State Pennsylvania Zip 16801 Phone # 8142313050 Email Address [email protected] List the names, email Anna Nelson, President, CentreBike, [email protected] address and affiliation of all other individuals Kelly Doyle, AmeriCorps Member, State College Borough, [email protected] that are working with you on this Courtney Hayden, State College Borough, [email protected] application. List all bicycle, active CentreBike, Paul Rito, Vice President, [email protected] transportation, and transportation equity State College Cycling Club, Joe Lundberg, President, [email protected] advocacy groups in your community, if Nittany Mountain Biking Association, Neil Millar, President, [email protected] any. Provide the name and email of the Active Lions, Melissa Bopp, Associate Professor, [email protected] primary contact for each group. CentreMoves, Jeannine Lozier, Executive Committee, [email protected] NOTE: If the primary Penn State Cycling Club, Sam Carroll, President, [email protected] contact of a group is already listed above, Centre Region Bicycle Advisory Committee, Lydia Vandenberg, Secretary, [email protected] please list an alternative contact. -

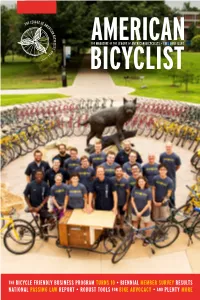

The Bicycle Friendly Business Program Turns 10 • Biennial

THE MAGAZINE OF THE LEAGUE OF AMERICAN BICYCLISTS • FALL 2018 ISSUE THE BICYCLE FRIENDLY BUSINESS PROGRAM TURNS 10 • BIENNIAL MEMBER SURVEY RESULTS NATIONAL PASSING LAW REPORT • ROBUST TOOLS FOR BIKE ADVOCACY • AND PLENTY MORE TABLE OF CONTENTS AMERICAN BICYCLIST • FALL 2018 2 Viewpoint: Shifting the Turning 10: The Bicycle Friendly Bicycling Movement to 10 Business Program Comes of Age Accelerate Progress By Executive Director Bill Nesper From breweries to churches, the Bicycle Friendly Business Program celebrates its first decade and IS NOVEMBER 27! 5 Enjoy the Ride: New League honors 1,250 companies that get people to pedal. Board Member Karin Weisburgh By Amelia Neptune. Finds Bike Safety Is Her Life’s Calling By Carly Adams 14 Making the Ascent: America’s Diverse Cities, Towns Make a United 6 Summer 2018: Clubs & Climb toward Bicycle Friendly Individuals Honor Roll Community Status 7 43,000 Cyclists Joined. The League’s Bicycle Friendly Community Program DOUBLE YOUR 20 Million Miles Pedaled. shares the map used by some of its recognized Challenge Accepted. towns and cities to climb their way to higher award IMPACT on By Christian Lampe levels. By Amelia Neptune. #GivingTuesday! 8 You Spoke. We Listened. University of Kentucky Takes Gold: Launched just six years ago, 18 Highlights of the 2018 A Bicycle Friendly University Case Study #GivingTuesday has grown Membership Survey to become a worldwide Sometimes you have to see how someone else has By Kevin Dekkinga done something to achieve it yourself. Witness the catalyst for good. creative investments and programs of the University Advocacy in Action: Last year alone, generous 24 of Kentucky, which cranked its way from Bicycle New Congress, New donors gave more than Friendly University Honorable Mention to Gold. -

March/April 2011

March-April 2011 AMERICAN www.bikeleague.org League of American Bicyclists Working for a Bicycle-Friendly America RED ROCK ROAD EXTREME ROAD MAKEOVER p. 10 16 Spring 2011 BFBs AND BFUs 18 NATIONAL BIKE SUMMIT 24 RIDE WITH LARRY The Bicycle Gives Freedom Back to a Parkinson’s Patient contentMARCH-APRIL 2011 IN EVERY ISSUE Viewpoint ......................................................... 2 Chair’s Message .............................................. 3 InBox .................................................................. 4 Cogs & Gears ................................................... 6 10 QuickStop ......................................................... 28 Bicycle Friendly ON THE America Workstand COVER! 10 Arizona’s Red Rock Road: How Community and Bicycling Advocacy Achieved an Extreme Road Makeover 14 Stanford Goes Platinum 16 Spring 2011 Bicycle Friendly Businesses and Bicycle Friendly Universities Think Bike 17 Introducing AdvocacyAdvance.org 18 National BIke Summit: Acting on a Simple Solution 18 From the Saddle 24 Ride With Larry Cover: Motorists and bicyclists now can safely share the scenic Red Rock Road between Sedona and the Village of Oak Creek. Red Rock photo above: VVCC member, Thomas McGoldrick, enjoys the bike lane of the new Red Rock Road between Sedona and the Village of Oak Creek. 24 AmericanBicyclist 1 AMERICAN viewpoint [Andy Clarke, president] THE LEAGUE OF AMERICAN BICYCLISTS The League of American Bicyclists, founded in 1880 as the League of American Wheelmen, promotes bicycling WE’RE for fun, fitness and transportation, and works through advocacy and education for a bicycle-friendly America. The League represents the interests of the nation’s 57 million bicyclists. With a current membership of 300,000 affiliated cyclists, including 25,000 individuals and 700 MOVING! organizations, the League works to bring better bicycling to your community. -

This Attached Letter

Adventure Cycling Association * America Walks * League of American Bicyclists * People for Bikes * Rails-to-Trails Conservancy * Ride of Silence * Safe Routes to School National Partnership * Alta Planning and Design * American College of Sports Medicine * American Society for Landscape Architects * Association of Pedestrian and Bicycle Professionals * Planet Bike * Alabama Bicycle Coalition (AlaBike) * Baldwin County Trailblazers * Walk Sitka * El Grupo Youth Cycling * BikeNWA-Bike North West Arkansas * Conway Advocates for Bicycling * Bike Walk Alameda * California Bicycling Coalition * Climate Action Santa Monica * Fresno Cycling Club * San Francisco Bicycle Coalition * Santa Monica Safe Streets Alliance * Santa Monica Spoke * Bicycle Colorado * Bike Colorado Springs * Bike Fort Collins * Pequot Cyclists * Bike Delaware * Washington Area Bicyclist Association * Dade Heritage Trust Inc. * Florida Bicycle Association * Gainesville Cycling Club * Naples Velo Bicycle Club * North Florida Bicycle Club * Sarasota Manatee Bicycle Club * Streets Alive of SWFL * Atlanta Bicycle Coalition * BIke FAYETTE * BikeAthens * Conyers Rockdale Bicycle and Trail Coalition * Georgia Bikes * Wheel Movement of the CSRA * Hawaii Bicycling League * PATH~ Peoples Advocacy for Trails Hawaii * Idaho Walk Bike Alliance * Evanston Bicycle Club * Friends of Cycling in Elk Grove * McHenry County Bicycle Advocates * Ride Illinois * Starved Rock Cycling Association * Bicycle Indiana, Inc. * Health by Design * J's Bikes Racing * National Road Bicycle Club * Iowa Bicycle -

Club Handbook

CLUB HANDBOOK November 2018 V3.20 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Membership Fees ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Club Constitution ............................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1. The Club .................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2. Membership............................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3. All General Meetings ................................................................................................................................ 6 1.4. Annual General Meetings (AGM) ............................................................................................................. 6 1.5. Extraordinary General Meetings (EGM) ................................................................................................... 6 1.6. The Committee .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.7. Committee meetings ................................................................................................................................. -

Cycling UK Impact Report 2018-19

Impact Report 2018-19 Cyclists’ Touring Club, operating as Cycling UK Cyclists’ Touring Club operating as Cycling UK 2018-19 Annual Report and Financial Statements, a company limited by guarantee, registered in England no: 25185. Registered as a charity in England and Wales charity no: 1147607 and in Scotland charity no: SC042541. Registered office: Parklands, Railton Road, Guildford, Surrey GU2 9JX page 1 Why cycling is the simple solution We want to inspire a million more people to cycle because we believe it’s the answer to many of society’s biggest problems. Air pollution is killing our children, obesity-related ill-health Some people lack the skills or are fearful of traffic. £6.1bn 36,000 crippling the NHS, congestion gridlocking our cities, and Others don’t have the motivation or the will. our love affair with the combustion engine contributing spent by NHS every year on deaths every year linked to a devastating climate crisis. And while cycling infrastructure remains patchy across obesity-related ill-health to air pollution in UK our towns and cities, it’s often too easy for people to The bike is a cheap, fun, healthy, environmentally friendly choose the car over the bike. alternative to driving, particularly over short distances. We want to inspire people to choose to cycle. But more than 70% of the UK population say they never cycle and only 2% of all journeys are made by bike. That’s why Cycling UK is on a mission to not only improve The reasons are complex. conditions for cycling but to change attitudes and behaviour. -

Cycle TOURING's FIRST COUPLE

TheCYCLE Pennells TOURING’S FIRST COUPLE ne day in August 1886, artist and cycling enthusiast Joseph BY DAVE BUCHANAN Pennell fell into conversation with two keen cyclists Oin a tavern in Yorkshire, England. The local wheelmen mentioned a recent magazine article about tricycling in Italy. It was written and illustrated, they explained, by “those Pennells” — the well-known American illustrator who “went around with his wife or his sister or something all over creation.” Joseph nodded politely and changed the subject. Little did the Yorkshiremen know that they were, in fact, talking to one of those very Pennells. This story, told by Joseph’s wife (not his sister), Elizabeth Robins Pennell, in The Life and Letters of Joseph Pennell, speaks to the minor celebrity enjoyed in the mid-1880s by this unconventional husband-and-wife creative duo from Philadelphia. In the final decades of the 19th century, they explored England and Europe by cycle and went on to publish five illustrated books about their trips, including A Canterbury Pilgrimage, An Italian Pilgrimage, and Over the Alps on a Bicycle, and dozens of illustrated magazine articles. The Pennells, with Elizabeth writing and Joseph illustrating, produced some of the earliest and best cycle- travel writing in the 1880s and ‘90s. In the process, they helped invent both leisure cycle touring and couples cycle touring. Unlike their more famous contemporary, Thomas Stevens — who set off on a high wheel bicycle in 1884 on a sensational globe-circling adventure, chronicled in his popular book Around the MUSEUM VICTORIA COURTESY ALBERT AND FREDERICK HOLLYER, World on a Bicycle (1887) — the Pennells didn’t seek high adventure in the remote outposts of the globe. -

Sports, Leisure and Days Out

Sports, Leisure and Days out rarechromo.org Sports, leisure and days out Something we all should enjoy is joining in with sports and leisure pursuits and enjoying a day out. For many children and adults, enjoying leisure pursuits is often complicated by obstacles thrown in their path. This guide has been written to prove that no matter what your ability, there is something for everyone out there and nothing is limitless if you can find the right support, training and organisation. There are many different types of sports and leisure pursuits available to anyone with a disability. In this guide we have included most of the popular ones but it is by no means an exhaustive list. This guide has been written to help signpost families whose children have a rare chromosome or gene disorder. The guide is aimed at those whose children are any age from pre-school to adult, whether they are mildly, moderately or severely affected, either mentally, physically or both. Because Cycling is one of the number one hobby that Unique families contact us about, a large part of the guide is dedicated to Cycling and access to facilites that allow your child to try different bikes to see what suits them. 2 CYCLING Who doesn ’t want to have a go at riding a bike? Most people love to ride and learning to ride a bicycle is a natural part of growing up for most children. It is fun and it is often something that families enjoy doing together. For a child affected by a rare chromosome or gene disorder and having physical and/or learning difficulties it can be a good way of increasing muscle tone and exercising. -

Nova Cycling Club

NOVA CYCLING CLUB The Ron Vaughan Memorial Open 25 mile Time Trial Incorporating the Manchester & NW VTTA 25 and Round 13 of the M&DTTA Cheshire Courses Points Competition Promoted for and on behalf of Cycling Time Trials under their Rules and Regulations To be held on Saturday, 8th July 2017 on the J4/8 course Event HQ : Goostrey Village Hall CW4 8DT (open from 12.30pm) Event Sec: Ian Ross First rider off : 2.18 pm 26 Brook Road Lymm Cheshire Time Keepers: Tony Millington & Graham Lawrence WA13 9AH Tel: 01925 755080 Mob: 07775953979 Prize Values & Awards 1st Fastest £45 1st Vet on Std £30 2nd Fastest £40 2nd Vet on Std £25 3rd Fastest £35 3rd Vet on Std £20 4th Fastest £30 4th Vet on Std £15 5th Fastest £25 Team (Bidlake system) £10 each 1st Man & NW Vet on Std £25 (Fastest 3rd rider) 2nd Man & NW Vet on Std £20 One rider one prize except teams The fastest rider to hold the Nova CC Ron Vaughan Memorial Trophy for 12 months. The fastest M&NW VTTA rider with the best aggregate standard times from both the Nova CC / M&DLCA 25 and the Seamons CC 25 (29/07/17) to hold the VTTA Manchester & North West Group 25 Mile Championship Cup for 12 months. J4/8 Course details: Start – On B5081 (Byley Road) at the 1st field gate after Kings Lane, and in line with the left-hand field gate post approx. ½ mile south of the B5082 (Three Greyhounds Public House). Proceed south along the B5081 to Byley Crossroads 0.7 miles, left along Moss Lane/Byley Lane to join A50 at Cranage 2.8. -

Bicycle Friendly Community Action Plan

Bicycle Friendly Community Action Plan MIAMISBURG/MIAMI TOWNSHIP, OHIO January, 2009 BICYCLE FRIENDLY COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: .................................................................................................1 1. OVERVIEW.............................................................................................................2 2. ENGINEERING.........................................................................................................5 3. EDUCATION ......................................................................................................... 10 4. ENCOURAGEMENT.................................................................................................. 13 5. ENFORCEMENT ..................................................................................................... 16 6. EVALUATION ........................................................................................................ 17 7. NEXT STEPS ......................................................................................................... 19 APPENDIX............................................................................................................... 20 Acknowledgements: This document provides a Bicycle Friendly Community Action Plan for Miamisburg/Miami Township, Ohio. The process for developing this plan was based on the national Bicycle Friendly Communities (BFC) program of the League of American Bicyclists. The Miami Valley Regional Planning Commission (MVRPC) provided staff