Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lapaglia Final Final Dissertation in Template 2019 22 Mar 2019

A CULTURAL GENEALOGY OF STRATEGIC RATIONALITY A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Liberal Studies By Gino R LaPaglia, M.S. Washington, DC April 10, 2018 Copyright 2018 by Gino R LaPaglia All Rights Reserved !ii A CULTURAL GENEALOGY OF STRATEGIC RATIONALITY Gino R. LaPaglia, M.S. Thesis Advisor: Francis Ambrosio, Ph.D ABSTRACT I construct in this thesis a cultural genealogy to trace in Western civilization a consistent set of values that underlie a worldview that I call Strategic Intelligence (SI). I argue that the plethora of cultural data indicates the presence both of an underlying strategic rationality and a metaphorological paradigm that functions at a level that is more expansive than the terminological and conceptual. I conclude that the values of SI have been transmitted in cultural sources for thousands of years, in multiple cultures. Invested with the highest forms of authority, the continuous transmission of the values of SI in two distinct civilizations (European, Chinese) over the trajectory of their unique cultural evolution provides evidence for the authority, legitimacy and potency of this ancient framework of meaning as fundamental to culture. (Keywords: Strategic Intelligence, Strategic Rationality, Philosophy of Strategy, Philosophical Anthropology, Hermeneutic Philosophy, Axiology, Metaphorical Analysis, Cultural Studies, Mētic) !iii The research and writing of this thesis is dedicated to everyone who helped along the way. Foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to the two professors who most influenced the course of my doctoral studies, my advisor Dr. -

Tantra: the Yoga of Sex

Tantra: The Yoga Of Sex OMAR GARRISON $12.00/PHILOSOPHY (Canada: $16.00) Revealing the ancient secrets and rituals of Hindu wis dom, Tantra: The Yoga of Sex teaches modern readers how to gain the mental and physical control over their bodies that will enable them to extend the ecstasy of sexual union far beyond their former experience. Combining philosophical concepts with physical exer cises and instructions in mental concentration, Omar V. Garrison explains how to harness the power inherent in sex in order to achieve an elevated state of consciousness - the ultimate union of the spiritual with the sensual. A journey through the wisdom of the ages, as well as a guide to sensual pleasure, Tantra: The Yoga of Sex leads the way to the mystical marriage of God and man. "Never before have I examined a text that presents the sexual union of humans and the preliminary relationships leading up to that goal as lovingly, beautifully, and hopefully as Tantra: The Yoga of Sex. " WILLIAM S. KROGER, M.D. OMAR V. GARRISON is a distinguished foreign correspondent. He studied for holy orders in the Episcopal church before becoming fascinated with Hindu philosophy and Tantra, which he studied in India. Cover design by Barbara Basb ISBN 0-517-54948-4 TANTRA:The Yoga OF Sex OMAR V. GARRISON HARMONY BOOKS/NEW YORK Copyright © MCMLXIV by Omar V. Garrison All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Edifying Parables

Edifying Parables of His Holiness Jagadguru Sri Abhinava Vidyatheertha Mahaswamigal Publisher Sri Vidyatheertha Foundation Chennai www.svfonline.net First Edition 1995 (1200 Copies) Reprint 2000 (1500 Copies) 2004 (3000 Copies) 2014 (1200 Copies) 2015 (2000 Copies) Digital Version 2016 © All rights reserved ISBN 81-903815-4-7 Published by: Sri Vidyatheertha Foundation G-B, Sai Karuna Apartments 49, Five Furlong Road Guindy, Chennai - 600 032 Mobile : 90031 92825 Email: [email protected] This E-Book is for free distribution only. 6 Edifying Parables Preface His Holiness Jagadguru Sri Abhinava Vidyatheertha Mahaswamigal, reverentially referred to as ‘Acharyal’ in this book, had an innate ability to explain even complex topics in a simple manner through stories composed by Him on the spot or based on texts such as the Vedas, Ramayana, Mahabharata and Puranas. This book contains well over a hundred edifying parables of our Acharyal compiled by a disciple and grouped over 97 heads. The sources of the parables are Acharyal’s benedictory addresses and His private conversations with the disciple. Following are the minor liberties that have been taken in the preparation of the text: 1. Parables narrated by Acharyal in more than one benedictory address have been grouped under a single head. 2. In rare cases, names have been given to the characters of a story even when Acharyal did not do so during His talk with the disciple. 3. Where Acharyal has narrated more than one version of a story, information from all the versions have been utilised. 7 We are glad in publishing the digital version of this book and offering it to all for free-download in commemoration of the birth-centenary of His Holiness Jagadguru Sri Abhinava Vidyatheertha Mahaswamigal. -

War in Ancient India

DELHI UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 7 DELHI UNIVERSITY LIBRARY a . n o . * > 8 Ac* No, ^ b { c l ^7 Datc °* please for loan This book should be returned on or before the date last stamped below. An overdue charge o f 5 PaU« will be collected for each day the book is kept overtime, J r - f j y i j «* *, ~ < f ■ :•~vr* ; S * --------1 t ____ i | / ( y \ O'?' " < / r , ■ / .... / Wa r in an cien t indIA. BY THE SAME AUTHOB Hindu Admiiflstrative Institutions. > Studies in Tamil Literature & History The Mauryan Polity. Do. a pamphlet in the Minerva series on Indian Government. Some Aspects of Vayu Puraiia. The Matsya Purana—a study. Bharadvaja&iksa. Silappadik&ram. The LalitS Cult. \/kulottunga Chola III (in Tamil). WAR IN ANCIENT INDIA BY V. R. RAMACHANDRA DIKSHITAR, m . a . University of Madras WITH A FOREWORD BY Lt.-Col. Dewan Bahadtjb Dr. A. LAKSIIMANASWAMI MUDALIAIi, M.D., LL.D., D.SC., F.R.C.O.G., F.A.C.S. Vice-Chanccllor, University of Madras MACMILLAN. AND CO. LIMITED MADRAS,'BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, LONDON 1941 FOREWORD I deem it a privilege to be given the opportunity of writing a foreword to this excellent publication, War . in 'Ancient India, at the request of the author, Mr. V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar. Mi*. Dikshitar’s works have attracted the notice of scholars, both in the East and the West, and some of his classics like the Silappadikaram, have justly'won for him wide appreciation. In bringing out this monumental work on War in Ancient India, at this particular juncture, Mr. -

Of Masala: an Analysis of Indian Spices As a Psychological Healer Based on Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’S the Mistress of Spices

NEW LITERARIA- An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities Volume 2, No. 2, July- August, 2021, PP. 08-15 ISSN: 2582-7375 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.48189/nl.2021.v02i2.002 www.newliteraria.com The “Magic” of Masala: An Analysis of Indian Spices as a Psychological Healer based on Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s The Mistress of Spices Gutimali Goswami Abstract India, the land of Ayurveda, is regarded as the cradling ground of knowledge relating to being and healing. The methodical and holistic system of medicine suggested by various Vedas and Purana-s of India often targeted the diseased and not the disease. Hence, utmost importance was given to the internal of a human being, its mind or manas. An imbalance in the psychological existence or functioning was believed to be the root cause of every subsequent vyadhi or ailment that followed up and impacted the human body. To maintain a sound relationship between the mind and the body various readily available banaspati or plant- derived were also suggested. They were introduced in form of spices which were popularly known as masala. Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni in her novel The Mistress of Spices utilizes the “magic” of these spices, both literally and metaphorically, and presents it as a psychological healer. She, through this novel, reminds us of the “medical charms” of the Indian spices which is undoubtedly a fundamental part of our cultural landscape. This paper, in a brief and comprehensive manner, attempts to analyze the ancient Indian belief system surrounding the key terms “health” and “healing” and presents it to the readers with the support of a fictional plot for better understanding. -

The Agni Purana's Virtues

8. AGNI PURANA Preliminaries In the forest that is known as Naimisharanya, Shounaka and the other rishis (sages) were performing a yajna (sacrifice) dedicated to the Lord Vishnu. Suta had also come there, on his way to a pilgrimage. www.YouSigma.com The sages told Suta, "We have welcomed you. Now describe to us that which makes men all- knowing. Describe to us that which is the most sacred in the whole world". Suta replied, "Vishnu is the essence of everything. I went to a hermitage named Badrika with Shuka, Paila and other sages and met Vyadeva there. Vyasadeva described to me that which he had learnt from the great sage Vashishtha, Vashishtha having learnt it from the god Agni himself. The Agni Purana is sacred because it tells us about the essence of the Brahman (the divine essence). I learnt all this from Vyasadeva and I will now tell you all that I have learnt." Avataras Do you know what an avatara is? An avatara is an incarnation and means that a god adopts a human form to be born on earth. Why do gods do this. The purpose is to destroy evil on earth and establish righteousness. Vishnu is regarded as the preserver of the universe and it is therefore Vishnu's incarnations that one encounters most often. Vishnu has already had nine such incarnations and the tenth and final incarnation is due in the future. These ten incarnations of Vishnu are as follows. (1) Matsya avatara- fish incarnation (2) Kurma avatara- turtle incarnation (3) Varaha avatara- boar incarnation (4) Narasimha avatara- half-man lion incarnation (5) Vamana avatara- dwarf incarnation (6) Parashurama (7) Rama (8) Krishna (9) Buddha (10) Kalki-this is the incarnation that is yet to come. -

Hindu Dharma Samudaya of Bhutan Post Box No

Hindu Dharma Samudaya of Bhutan Post Box No. 167, Babesa, Thimphu, Bhutan. Tel. +975-2-329245 Fax +975-2-326267; E-mail: [email protected] Prepared by Vivekananda Saraswati 1 BAALBIKAAS COURSES FIRST CLASES FIRS STEP - Prayer Mantras • Asato Ma Sat Gamaya. Tamaso Ma Jyotirgamaya. Mrityor Ma Amritam Gamaya. • Om Shaantih, Shaantih, Shaanti • Lead me on from unreal to Real, from darkness to Light, from mortality to Immortality. • This is the best prayer; the prayer for the Light, for the Truth, for Immortality. • Om Saha Naa-Avatu | Saha Nau Bhunaktu | Saha Viiryam Karavaavahai | • Tejasvi Naav[au]-Adhiitam-Astu Maa Vidvissaavahai | • Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih || Meaning: 1: Om, Together may we two Move (in our Studies, the Teacher and the Student), 2: Together may we two Relish (our Studies, the Teacher and the Student), 3: Together may we perform (our Studies) with Vigour (with deep Concentration), 4: May what has been Studied by us be filled with the Brilliance (of Understanding, leading to Knowledge); May it Not give rise to Hostility (due to lack of Understanding), 5: Om Peace, Peace, Peace. (May that Knowledge give rise to Peace in the three levels - Bhautik, Pranik and Aatmik) Chapter-19 There is Only Suffering in this World • Birth is suffering; disease is suffering; death is suffering; sorrow, grief, pain, lamentations are suffering; union with unpleasant objects is suffering; separation from the beloved objects is suffering; unsatisfied desires are suffering. O man! Is there any real pleasure or happiness in this world? Why do you cling to these mundane objects? Why do you stroll about here and there like a street-dog in search of happiness in this earth-plane? Search within. -

Visistadvaita.Pdf

Visistadvaita A Philosophy of Religion K.R.Paramahamsa 1 2 Table of Contents Page No Preface 5 1. Visistadvaita - A Darsana 7 2. The Theory of Knowledge 12 General 12 Dharmabhuta-jnaana (Phenomenological Consciousness) 15 Svarupa-jnaana (Existential Consciousness) & Dharmabhuta-jnaana (Phenomenological Consciousness) -Interrelationship 19 3. The Theory of Judgment 22 4. The Theory of Relations 25 5. Truth, Error and Avidya 28 Truth 28 Error 30 Avidya 33 6. Saguna Brahman 37 The Brahman as Adhara 44 The Brahman as Satya 47 The Brahman as Jnaana 50 The Brahman as Ananta 54 The Brahman as Bhuvana Sundara 57 The Brahman as Saririn 65 The Brahman as Sesin 71 The Brahman as Niyantr 75 The Brahman as Redeemer 82 7. Cosmology 91 8. The Psychology of Jivatman 94 9. Mukti-Mumuksutva 99 Mukti 99 Mumuksutva 105 10. Ways to Salvation 107 Karma-yoga 107 Jnaana-yoga 109 Bhakti-yoga 112 Prapatti-yoga 117 11. The Mysticism of Visistadviata 123 3 12. The Theology of Srivaisnavism 127 13. Srivaisnavism of Visistadvaita 131 14. Evolution of Vaisnavism 136 Narayana-Visnu 136 Sankarsana-Baladeva 139 Pancaraatra 144 4 Preface Visistadvaita, as a philosophy of religion, not only interprets metaphysics in terms of religion, and religion in terms of metaphysics, but equates the two by the common designation darsana. Darsana connotes a Vedanta philosophical system as well as spiritual perception of Reality, and may be explained as an integral intuition of the Brahman. In extreme monism, the Brahman is jnaana and is realized by jnaana. Extreme theism distrusts the intellect and relies on scriptural faith. -

Visistadvaita a Philosophy of Religion

Visistadvaita A Philosophy of Religion K.R.Paramahamsa 1 Dedicated to the Being of Sri Sathya Sai TAT Embodied 2 3 Table of Contents Page No Preface 7 1. Visistadvaita - A Darsana 11 2. The Theory of Knowledge 19 General 19 Dharmabhuta-jnaana(Phenomenological Consciousness) 24 Svarupa-jnaana(Existential Consciousness) & Dharmabhuta-jnaana (Phenomenological Consciousness)-Interrelationship 31 3. The Theory of Judgment 36 4. The Theory of Relations 41 5. Truth, Error and Avidya 46 Truth 46 Error 49 Avidya 54 6. Saguna Brahman 62 The Brahman as Adhara 74 The Brahman as Satya 79 The Brahman as Jnaana 83 The Brahman as Ananta 91 The Brahman as Bhuvana Sundara 96 The Brahman as Saririn 110 The Brahman as Sesin 121 The Brahman as Niyantr 128 The Brahman as Redeemer 141 7. Cosmology 157 8. The Psychology of Jivatman 162 9. Mukti-Mumuksutva 170 Mukti 170 Mumuksutva 181 4 5 10.Ways to Salvation 185 Preface Karma-yoga 185 Jnaana-yoga 189 Visistadvaita, as a philosophy of religion, not only interprets Bhakti-yoga 195 metaphysics in terms of religion, and religion in terms of Prapatti-yoga 204 metaphysics, but equates the two by the common designation 11.The Mysticism of Visistadviata 216 darsana. Darsana connotes a Vedanta philosophical system as 12.The Theology of Srivaisnavism 223 well as spiritual perception of Reality, and may be explained as an 13.Srivaisnavism of Visistadvaita 231 integral intuition of the Brahman. 14.Evolution of Vaisnavism 240 Narayana-Visnu 240 In extreme monism, the Brahman is jnaana and is realized Sankarsana-Baladeva 246 by jnaana. -

Dbet Alpha PDF Version © 2017 All Rights Reserved

SHINGON TEXTS dBET Alpha PDF Version © 2017 All Rights Reserved BDK English Tripitaka 98-1, II, III, iy VI, VII SHINGON TEXTS On the Differences between the Exoteric and Esoteric Teachings The Meaning of Becoming a Buddha in This Very Body The Meanings of Sound, Sign, and Reality The Meanings of the Word Hum The Precious Key to the Secret Treasury by Kukai Translated from the Japanese (Taisho Volume 77, Numbers 2427, 2428, 2429, 2430, 2426) by Rolf W. Giebel The Mitsugonin Confession The Illuminating Secret Commentary on the Five Cakras and the Nine Syllables by Kakuban Translated from the Japanese (Taisho Volume 79, Numbers 2527, 2514) by Dale A. Todaro Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research 2004 © 2004 by Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai and Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transcribed in any form or by any means —electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise— without the prior written permission of the publisher. First Printing, 2004 ISBN: 1-886439-24-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2003114203 Published by Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research 2620 Warring Street Berkeley, California 94704 Printed in the United States of America A Message on the Publication of the English Tripitaka The Buddhist canon is said to contain eighty-four thousand different teachings. I believe that this is because the Buddha’s basic approach was to prescribe a different treatment for every spiritual ailment, much as a doctor prescribes a different medicine for every medical ailment. -

Essence of Shiva Ratri Mahima V D N

ESSENCE OF SHIVA RATRI MAHIMA V D N RAO 1 Compiled, composed and interpreted by V.D.N.Rao, former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, now at Chennai. Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Essence of Brahma Sutras Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta of Knowledge of Numbers Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Austerities Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Essence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas Smriti- and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Essence of Maha Narayanopashid; Essence of Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Maitri Upanishad Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi; Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Essence of Bhagya -Bhogya-Yogyata Lakshmi Paraashara -

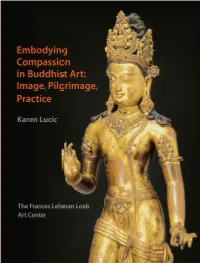

Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice

Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice THE FRANCES LEHMAN LOEB ART CENTER Embodying Compassion 1 Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice Karen Lucic The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center 2 Embodying Compassion Embodying Compassion 3 Lenders and Donors to the Exhibition Contents American Museum of Natural History, New York 6 Acknowledgments Asia Society, New York 7 Note to the Reader Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art 9 Many Faces, Many Names: Avalokiteshvara, Bodhisattva of Compassion The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 49 Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: The Newark Museum Catalogue Entries Princeton University Art Museum 49 Image The Rubin Museum of Art, New York 59 Pilgrimage Daniele Selby ’13 65 Practice 73 Glossary 76 Sources Cited 80 Photo Credits Front cover illustration: Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (detail), Nepal, The exhibition and publication ofEmbodying Compassion in Transitional period, late 10th–early 11th century; gilt copper alloy with Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice are supported by inlays of semiprecious stones; 26 3/4 x 11 1/2 x 5 1/4 in.; Asia Society, E. Rhodes & Leona B. Carpenter Foundation; The Henry Luce New York, Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.47. Foundation; ASIANetwork Luce Asian Arts Program; John Stuart Gordon ’00; Elizabeth Kay and Raymond Bal; Ann Kinney Back cover illustration: Kannon (Avalokiteshvara), (detail), Japanese, ’53 and Gilbert Kinney. It is organized by The Frances Lehman Edo period (1615–1868); hanging scroll, ink and color on silk; image: Loeb Art Center and on view from April 23 to June 28, 2015. 61 7/8 x 33 in., mount: 87 7/8 x 39 1/2 in.; Gift of Daniele Selby ’13, The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, 2014.20.1.