War in Ancient India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reasoning As a Science, Its Role in Early Dharma Literature, and the Emergence of the Term Nyāya

Reasoning as a Science, its Role in Early Dharma Literature, and the Emergence of the Term nyāya KARIN PREISENDANZ THE CULTURAL BACKGROUND OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF LOGIC IN INDIA Previous research on the early development of Indian logic and its cultural background has placed a great deal of emphasis on the evi- dence provided by the early classical Āyurvedic tradition. To be sure, the probably already pre-classical tradition of debate with its inherent concern about convincing and correct procedures of proof contains important seeds for the development of logic, and its treat- ment found a special place in the Carakasaühitā. I will discuss in detail elsewhere the diametrically opposed positions of the pioneer- ing Indian scholars in this area, namely, Satishchandra Vidyabhusa- na and Surendranath Dasgupta, as regards the relationship between, on the one hand, the medical tradition, and, on the other, the early theories about debate and reflections on the proto-logical concepts embedded in it as exemplified by the Carakasaühitā.1 In this con- nection I take a middle position between their rather extreme views and attempt to demonstrate the particular importance of debate – responsible for an intense intellectual interest in it – in the medical context, drawing on the diverse evidence provided by the Caraka- saühitā itself. This interest, I argue, not only led to some specific- 1 Cf. Preisendanz, forthcoming. 28 KARIN PREISENDANZ ally medical theoretical treatment of the types of debate, their con- stitutive elements and their structure by -

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

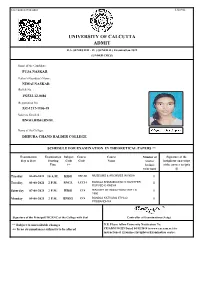

University of Calcutta Admit

532/1800865758/0401 5320942 UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA ADMIT B.A. SEMESTER - IV ( GENERAL) Examination-2021 (UNDER CBCS) Name of the Candidate : PUJA NASKAR Father's/Guardian's Name : NIMAI NASKAR Roll & No. : 192532-12-0486 Registration No. 532-1212-1106-19 Subjects Enrolled : BNGG,HISG,BNGL Name of the College : DHRUBA CHAND HALDER COLLEGE SCHEDULE FOR EXAMINATION IN THEORETICAL PAPERS ** Examination Examination Subject Course Course Number of Signature of the Day & Date Starting Code Code Name Answer invigilator on receipt Time ++ book(s) of the answer script/s to be used @ Tuesday 03-08-2021 10 A.M. HISG SEC-B1 MUSEUMS & ARCHIVES IN INDIA 1 Tuesday 03-08-2021 2 P.M. BNGL LCC2-1 BANGLA BHASABIGYAN O SAHITYER 1 RUPVED O KABYA Saturday 07-08-2021 2 P.M. HISG CC4 HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1 1950 Monday 09-08-2021 2 P.M. BNGG CC4 BANGLA KATHASAHITYA O 1 PROBANDHYA Signature of the Principal/TIC/OIC of the College with Seal Controller of Examinations (Actg.) ** Subject to unavoidable changes N.B. Please follow University Notification No. ++ In no circumstances subject/s to be altered CE/ADM/18/229 Dated 04/12/2018 in www.cuexam.net for instruction of Examinee/Invigilator/Examination centre. 532/1800908303/0402 5320963 UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA ADMIT B.A. SEMESTER - IV ( GENERAL) Examination-2021 (UNDER CBCS) Name of the Candidate : JABA MONDAL Father's/Guardian's Name : SUBARNA MONDAL Roll & No. : 192532-12-0487 Registration No. 532-1212-1126-19 Subjects Enrolled : HISG,SOCG,BNGL Name of the College : DHRUBA CHAND HALDER COLLEGE SCHEDULE FOR EXAMINATION IN THEORETICAL PAPERS ** Examination Examination Subject Course Course Number of Signature of the Day & Date Starting Code Code Name Answer invigilator on receipt Time ++ book(s) of the answer script/s to be used @ Tuesday 03-08-2021 10 A.M. -

Literary Evidences of Agricultural Development in Ancient India

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2021; 7(2): 32-35 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2021; 7(2): 32-35 Literary evidences of agricultural development in © 2021 IJSR www.anantaajournal.com ancient India Received: 28-01-2021 Accepted: 30-02-2021 Lagnajeeta Chakraborty Lagnajeeta Chakraborty Assistant Professor, Sanskrit, Introduction North Bengal University, West Bengal, India No animal can live without food. Food is the basic need of each and every being. We should remember that we eat to live, not live to eat. In course of evolution when human beings appeared in this planet, they wandered from one place to another in search of food. They were then hunters and food collectors. They hunted wild animals with the help of stone, sticks etc. and collected fruits and roots from forests. In this pre-historic age human beings were nomads. Gradually they advanced towards developed livelihood. They learnt the technology of burning fire and next the know-how of agriculture. Agriculture entirely changed the human habitats. It is one of the most important inventions of human society. With the invention and development of agriculture, pre-historic people left their nomadic lives and settled down villages. Some famous civilizations were established with the growth of agriculture. It is noted that all this oldest Civilizations were formed on the valley of rivers. Cities and towns were set up based on the agricultural industries. Here we are going to discuss about the agricultural activities in ancient India. Most probably agriculture in India began by 9000 BC [1]. From that very period, cultivation of plants and domestication of crops and animals were started. -

Introduction to BI-Tagavad-Gita

TEAcI-tER'S GuidE TO INTROduCTioN TO BI-tAGAVAd-GiTA (DAModAR CLASS) INTROduCTioN TO BHAqAVAd-qiTA Compiled by: Tapasvini devi dasi Hare Krishna Sunday School Program is sponsored by: ISKCON Foundation Contents Chapter Page Introduction 1 1. History ofthe Kuru Dynasty 3 2. Birth ofthe Pandavas 10 3. The Pandavas Move to Hastinapura 16 4. Indraprastha 22 5. Life in Exile 29 6. Preparing for Battle 34 7. Quiz 41 Crossword Puzzle Answer Key 45 Worksheets 46 9ntroduction "Introduction to Bhagavad Gita" is a session that deals with the history ofthe Pandavas. It is not meant to be a study ofthe Mahabharat. That could be studied for an entire year or more. This booklet is limited to the important events which led up to the battle ofKurlLkshetra. We speak often in our classes ofKrishna and the Bhagavad Gita and the Battle ofKurukshetra. But for the new student, or student llnfamiliar with the history ofthe Pandavas, these topics don't have much significance ifthey fail to understand the reasons behind the Bhagavad Gita being spoken (on a battlefield, yet!). This session will provide the background needed for children to go on to explore the teachulgs ofBhagavad Gita. You may have a classroonl filled with childrel1 who know these events well. Or you may have a class who has never heard ofthe Pandavas. You will likely have some ofeach. The way you teach your class should be determined from what the children already know. Students familiar with Mahabharat can absorb many more details and adventures. Young children and children new to the subject should learn the basics well. -

Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Central Vista.Pdf

RASHTRAPATI BHAVAN and the Central Vista © Sondeep Shankar Delhi is not one city, but many. In the 3,000 years of its existence, the many deliberations, decided on two architects to design name ‘Delhi’ (or Dhillika, Dilli, Dehli,) has been applied to these many New Delhi. Edwin Landseer Lutyens, till then known mainly as an cities, all more or less adjoining each other in their physical boundary, architect of English country homes, was one. The other was Herbert some overlapping others. Invaders and newcomers to the throne, anxious Baker, the architect of the Union buildings at Pretoria. to leave imprints of their sovereign status, built citadels and settlements Lutyens’ vision was to plan a city on lines similar to other great here like Jahanpanah, Siri, Firozabad, Shahjahanabad … and, capitals of the world: Paris, Rome, and Washington DC. Broad, long eventually, New Delhi. In December 1911, the city hosted the Delhi avenues flanked by sprawling lawns, with impressive monuments Durbar (a grand assembly), to mark the coronation of King George V. punctuating the avenue, and the symbolic seat of power at the end— At the end of the Durbar on 12 December, 1911, King George made an this was what Lutyens aimed for, and he found the perfect geographical announcement that the capital of India was to be shifted from Calcutta location in the low Raisina Hill, west of Dinpanah (Purana Qila). to Delhi. There were many reasons behind this decision. Calcutta had Lutyens noticed that a straight line could connect Raisina Hill to become difficult to rule from, with the partition of Bengal and the Purana Qila (thus, symbolically, connecting the old with the new). -

93. Sudarsana Vaibhavam

. ïI>. Sri sudarshana vaibhavam sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Annotated Commentary in English By: Oppiliappan Koil SrI VaradAchAri SaThakopan 1&&& Sri Anil T (Hyderabad) . ïI>. SWAMY DESIKAN’S SHODASAYUDHAA STHOTHRAM sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org ANNOTATED COMMENTARY IN ENGLISH BY: OPPILIAPPAN KOIL SRI VARADACHARI SATHAGOPAN 2 CONTENTS Sri Shodhasayudha StOthram Introduction 5 SlOkam 1 8 SlOkam 2 9 SlOkam 3 10 SlOkam 4 11 SlOkam 5 12 SlOkam 6 13 SlOkam 7 14 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org SlOkam 8 15 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org SlOkam 9 16 SlOkam 10 17 SlOkam 11 18 SlOkam 12 19 SlOkam 13 20 SlOkam 14 21 SlOkam 15 23 SlOkam 16 24 3 SlOkam 17 25 SlOkam 18 26 SlOkam 19 (Phala Sruti) 27 Nigamanam 28 Sri Sudarshana Kavacham 29 - 35 Sri Sudarshana Vaibhavam 36 - 42 ( By Muralidhar Rangaswamy ) Sri Sudarshana Homam 43 - 46 Sri Sudarshana Sathakam Introduction 47 - 49 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Thiruvaymozhi 7.4 50 - 56 SlOkam 1 58 SlOkam 2 60 SlOkam 3 61 SlOkam 4 63 SlOkam 5 65 SlOkam 6 66 SlOkam 7 68 4 . ïI>. ïImteingmaNt mhadeizkay nm> . ;aefzayuxStaeÇt!. SWAMY DESIKAN’S SHODASAYUDHA STHOTHRAM Introduction sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Shodasa Ayutha means sixteen weapons of Sri Sudarsanaazhwar. This sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Sthothram is in praise of the glory of Sri Sudarsanaazhwar who is wielding sixteen weapons all of which are having a part of the power of the Chak- rAudham bestowed upon them. This Sthothram consists of 19 slOkams. The first slOkam is an introduction and refers to the 16 weapons adorned by Sri Sudarsana BhagavAn. -

Indian History - Dynasties #4

TISS GK Preparation | Indian History - Dynasties #4 TISS GK Preparation Series: GK is a very important section for TISS especially since the verbal and the quant sections are relatively easy. Hence, getting a good score in GK can easily be the difference between getting a TISS call and not getting one. To help you ace this section, we are starting a series of articles devoted to topics commonly asked in the TISS GK section. We hope that this will help you in your preparation. Every article will also be available in PDF format. Here is our #4 article in this series: Indian History – Dynasties. Indian History is a very important topic for TISS with a lot of questions asked on dynasties, ancient India, etc. To help you, we have compiled a list of the important dynasties of India with a little detail on each. Also, this has been presented in a chronological order. Sr. Dynasty/Empire Detail No. 1 Magadha The core of this kingdom was the area of Bihar south of the Ganges; its first capital was Rajagriha (modern Rajgir) then Pataliputra (modern Patna). Magadha played an important role in the development of Jainism and Buddhism, and two of India's greatest empires, the Maurya Empire and Gupta Empire, originated from Magadha. 2 Maurya The Maurya Empire (322–185 BCE) was the first empire to unify India into one state, and was the largest on the Indian subcontinent. The empire was established by Chandragupta Maurya in Magadha (in modern Bihar) when he overthrew the Nanda Dynasty. Chandragupta's son Bindusara succeeded to the throne around 297 BC. -

The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen

The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen To cite this version: Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen. The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and philological papers on a Vedic tradition. Arlo Griffiths; Annette Schmiedchen. 11, Shaker, 2007, Indologica Halensis, 978-3-8322-6255-6. halshs-01929253 HAL Id: halshs-01929253 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01929253 Submitted on 5 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Griffiths, Arlo, and Annette Schmiedchen, eds. 2007. The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and Philological Papers on a Vedic Tradition. Indologica Halensis 11. Aachen: Shaker. Contents Arlo Griffiths Prefatory Remarks . III Philipp Kubisch The Metrical and Prosodical Structures of Books I–VII of the Vulgate Atharvavedasam. hita¯ .....................................................1 Alexander Lubotsky PS 8.15. Offense against a Brahmin . 23 Werner Knobl Zwei Studien zum Wortschatz der Paippalada-Sam¯ . hita¯ ..................35 Yasuhiro Tsuchiyama On the meaning of the word r¯as..tr´a: PS 10.4 . 71 Timothy Lubin The N¯ılarudropanis.ad and the Paippal¯adasam. hit¯a: A Critical Edition with Trans- lation of the Upanis.ad and Nar¯ ayan¯ . a’s D¯ıpik¯a ............................81 Arlo Griffiths The Ancillary Literature of the Paippalada¯ School: A Preliminary Survey with an Edition of the Caran. -

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 5, Issue 4 April 2011

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 5, Issue 4 April 2011 HARI OM March 1st, Swamiji returned from India where he visited holy places and sister branch in Bangalore. And a fruitful trip to Maha Sarovar (West Kolkata) water to celebrate Mahashivatri here in our temple Sunnyvale. Shiva Abhishekham was performed every 3 hrs with milk, yogurt, sugar, juice and other Dravyas. The temple echoed with devotional chanting of Shiva Panchakshari Mantram, Om Namah Shivayah. During day long Pravachan Swamiji narrated 2 special stories. The first one was about Ganga, and why we pour water on top of Shiva Linga and the second one about Bhasmasura. King Sagar performed powerful Ashwamedha Yagna (Horse sacrifice) to prove his supremacy. Lord Indra, leader of the Demi Gods, fearful of the results of the yagna, stole the horse. He left the horse at the ashram of Kapila who was in deep meditation. King Sagar's 60,000 sons (born to Queen Sumati) and one son Asamanja (born to queen Keshini) were sent to search the horse. When they found the horse at Shri N. Swamiji performing Aarthi KapilaDeva's Ashram, they concluded he had stolen it and prepared to attack him. The noise disturbed the meditating Rishi/Sage VISAYA VINIVARTANTE NIRAHARASYA DEHINAH| KapilaDeva and he opened his eyes and cursed the sons of king sagara for their disrespect to such a great personality. Fire emanced RASAVARJAM RASO PY ASYA from their own bodies and they were burned to ashes instantly. Later PARAM DRSTVA NIVARTATE || king Sagar sent his Grandson Anshuman to retreive the horse. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Barry Strauss

Faith for the Fight BARRY STRAUSS At a recent academic conference on an- cient history and modern politics, a copy of Robert D. Ka- plan’s Warrior Politics was held up by a speaker as an example of the current influence of the classics on Washing- ton policymakers, as if the horseman shown on the cover was riding straight from the Library of Congress to the Capitol.* One of the attendees was unimpressed. He de- nounced Kaplan as a pseudo-intellectual who does more harm than good. But not so fast: it is possible to be skeptical of the first claim without accepting the second. Yes, our politicians may quote Kaplan more than they actually read him, but if they do indeed study what he has to say, then they will be that much the better for it. Kaplan is not a scholar, as he admits, but there is nothing “pseudo” about his wise and pithy book. Kaplan is a journalist with long experience of living in and writing about the parts of the world that have exploded in recent decades: such places as Bosnia, Kosovo, Sierra Leone, Russia, Iran, Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan. Anyone who has made it through those trouble spots is more than up to the rigors of reading about the Peloponnesian War, even if he doesn’t do so in Attic Greek. A harsh critic might complain about Warrior Politics’ lack of a rigorous analytical thread, but not about the absence of a strong central thesis. Kaplan is clear about his main point: we will face our current foreign policy crises better by going *Robert D.