Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Central Vista.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profile of Delhi: National Capital Territory

Draft- State Profile Chapter II NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY - DELHI 2.1 General Characteristics Delhi is located in northern India BASIC STATISTICS ABOUT DELHI between the latitudes of 28°-24’-17” • Area: 1,483 sq.Km and 28°-53’-00” North and longitudes • Number of districts: 9 of 76°-50’-24” and 77°-20’-37” East. • Number of Urban villages: Delhi shares bordering with the States • Per Capita income: Rs. 38,864 of Uttar Pradeshand Haryana. Delhi (As per Census2000-01) has an area of 1,483 sq. kms. Its maximum length is 51.90 kms and greatest widthis 48.48 kms. Delhi is situated on the right bank of the river Yamuna at the periphery of the Gangetic plains. It lies a little north of 28 n latitude and a little to the west of 78 longitude. To the west and south-west is the great Indian Thar desert of Rajasthan state, formerly known as Rajputana and, to the east lies the river Yamuna across which has spread the greater Delhi of today. The ridges of the Aravelli range extend right into Delhi proper, towards the western side of the city, and this has given an undulating character to some parts of Delhi. The meandering course of the river Yamuna meets the ridge of Wazirabad to the north; while to the south, the ridge branches off from Mehrauli. The main city is situated on the west bank of the river. 2.2 Physical Features 2.2.1 Geography Delhi is bounded by the Indo-Gangetic alluvial plains in the North and East, by Thar desert in the West and by Aravalli hill ranges in the South. -

Princely Palaces in New Delhi Datasheet

TITLE INFORMATION Tel: +1 212 645 1111 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.accartbooks.com/us Princely Palaces In New Delhi Sumanta K Bhowmick ISBN 9789383098910 Publisher Niyogi Books Binding Hardback Territory USA & Canada Size 9.18 in x 10.39 in Pages 264 Pages Price $75.00 The first-ever comprehensive book on the princely palaces in New Delhi Documentation based on extensive archival research and interviews with royal families Text supported by priceless photographs obtained from the private collections of the princely states, National Archives of India, state archives and various other government and private bodies Rajas and maharajas from all over the British Indian Empire congregated in Delhi to attend the great Delhi Durbar of 1911. A new capital city was born New Delhi. Soon after, the princely states came up with elaborate palaces in the new Imperial capital Hyderabad House, Baroda House, Jaipur House, Bikaner House, Patiala House, to name a few. Why did the British government allot prime land to the princely states and how? How did the construction come up and under whose architectural design? Who occupied these palaces and what were the events held? What happened to these palatial buildings after the integration of the states with the Indian Republic? This book delineates the story behind the story, documenting history through archival research, interviews with royalty and unpublished photographs from royal private collections. Contents: Foreword; The Journey; Living with History; Hyderabad House- Guests of Honour; Baroda House - Butterfly on the Track; Bikaner House -Rajasthan Royals; Jaipur House -An Acre of Art; Patiala House -Chambers of Justice; Travancore House -Hathiwali Kothi; Darbhanga House - The 'Twain Shall Meet; The Other Palaces - Scattered Petals; Planning the Palaces -Thy Will be Done; List of Princely Palaces. -

Synergies in Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

Synergies in Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Report of the national consultation supported by Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, Geneva May 19, 2006 India Habitat Centre, New Delhi Synergies in Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Synergies in Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health * Report of the national consultation supported by Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, Geneva For more information, contact Dr. Deepti Chirmulay Dr. Aparajita Gogoi PATH WRAI A-9, Qutab Institutional Area C/o CEDPA New Delhi–110 067, India C-1, Hauz Khas Tel: 91-11-2653 0080 to 88 New Delhi–110 016, India Fax: 91-11-2653 0089 Tel: 91-11-5165 6781 to 85 Web: www.path.org Fax: 91-11-5165 6710 Email: [email protected] Web: whiteribbonalliance-india.org Email: [email protected] * This report was prepared in June 2006. Report of the national consultation supported by Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, 2 Geneva, organized by PATH and the White Ribbon Alliance. (May 19, 2006, New Delhi, India). Synergies in Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Background • In April 2005, the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (PMNCH) was launched at “Lives in the Balance,” a three-day international consultation convened in New Delhi. The consultation culminated with a proclamation of “The Delhi Declaration on Maternal, Newborn and Child Health.” • These global efforts to link and expand efforts on maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) are also reflected in Government of India (GOI) policy, programs and priorities, notably through the National Rural Health Mission and Reproductive and Child Health (RCH–II) program. -

Centrespread Centrespread 15 JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017 All the JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017

14 centrespread centrespread 15 JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017 All The JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017 takes you through ET Magazine Presidents’On Tuesday, Ram Nath Kovind moved in as the 14th President Houses to occupy Rashtrapati Bhawan, the official residence of the Indian President. the history and the peoplepresidential behind palacesthe palatial around residence, the world: and a glimpse into other :: Indulekha Aravind Presidential Residences Around The World ELYSEE PALACE, PARIS The official residence of the President of Rashtrapati Bhawan: A Brief History France since 1848, Elysee Palace was opened Cast Of Characters the building to move construction materials and subsoil water in 1722. An example of the French Classical pumped to the surface for all water requirements. style, it has 356 rooms spread over Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker 11,179 sq m n 1911, during the Delhi Durbar, it was decided that British The bulk of the land belonged to the then-maharaja of Jaipur, were the architects of the Viceroy’s India’s capital would be shifted from Calcutta to Delhi. With Sawai Madho Singh II, who gifted the 145-ft Jaipur Column to House and it was Lutyens who conceived THE WHITE HOUSE, the new capital, a new imperial residence also had to be the British to commemorate the creation of Delhi as the new the H-shaped building I WASHINGTON DC found. The original choice was Kingsway Camp in the north but capital. Though the initial idea was to finish the construction The home of the US President is spread it was rejected after experts said the region was at the risk of in four years, it finally took more than 17 years to complete, across six levels, with 132 rooms The main building was constructed under the supervision of flooding. -

Question. Which Is the Oldest Stadium in India

Weekly MCQs 27th November to 4th December Daily Current Affairs @7:30AM Live International News ➢ QS Asia University Rankings 2021: For the continent’s best higher education institutions ▪ The top-10 list doesn’t feature any Indian university. The top three Indian universities to feature on the Asia Rankings are IIT Bombay (Rank 47), IIT Delhi (Rank 50), and IIT Madras (Rank 56). ▪ A total of 107 Indian institutes made it to the overall QS Asia Rankings. Of them, 7 bagged a spot in the top 100. Daily Current Affairs @7:30AM Live International News ➢ QS Asia University Rankings 2021: For the continent’s best higher education institutions ➢ Top 5 University ▪ Rank 1:National University of Singapore (NUS), Singapore ▪ Rank 2: Tsinghua University, China (Mainland) ▪ Rank 3: Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore ▪ Rank 4: University of Hong Kong (HKU), Hong Kong SAR ▪ Rank 5: Zhejiang University, China (Mainland) Daily Current Affairs @7:30AM Live International News ➢ Global Terrorism Index (GTI) 2020: By Institute for Economics & Peace, is a global think tank headquartered in Sydney, Australia ▪ India has been ranked at 8th spot globally in the list of countries most affected by terrorism in 2019. ▪ With a score of 9.592, Afghanistan has topped the index as the worst terror impacted nation among the 163 countries. ▪ It is followed by Iraq (8.682) and Nigeria (8.314) at second and third place respectively. Daily Current Affairs @7:30AM Live International News ➢ New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern declared a climate emergency, telling parliament that urgent action was needed for the sake of future generations. -

9-Ravi-Agarwal-Ridge.Pdf

Fight for a forest RAVI AGARWAL From where comes this greenery and flowers? 15% of the city’s land, though much What makes the clouds and the air? of it has been flattened. The decidu- – Mirza Ghalib ous arid scrub forest of the ridge still provides an unique ecosystem, which THE battle for protecting Delhi’s today lies in the heart of the modern green lungs, its prehistoric urban for- city, and is critical for its ecological est, has never been more intense than health. Though citizen’s action has now. The newly global city, located in managed to legally protect1 about a cusp formed by the tail end of the 1.5 7800 ha of the forest scattered in four billion year old, 800 km long Aravalli mountain range as it culminates at the * Ravi Agarwal is member of Srishti and river Yamuna, is the aspirational capi- founding Director of Toxics Link, both envi- 48 tal of over 15 million people. ronmental NGOs. He has been involved in the ridge campaign since 1992, and was inducted The hilly spur known as the into the Ridge Management Board in 2005. Delhi Ridge once occupied almost He is an engineer by training. SEMINAR 613 – September 2010 distinct patches, the fight for the ridge besides protecting the city from desert Dynasty in the 13th and 14th centuries forest has been long and is ongoing. sands blowing in from Rajasthan and marked by the towering Qutab Land is scarce, with competing uses (south of Delhi). Most importantly, for Minar. in the densely populated city, sur- an increasingly water scarce city, the rounded by increasingly urbanized ridge forest and the river Yamuna once peripheral townships of Gurgaon, formed a network of water channels, Even though the Delhi Ridge forest Faridabad and Noida. -

WARD 62-S, HAUZ KHAS Izfrcaf/Kr RESTRICTED Dsoy Fohkkxh; Á;®X Gsrq for DEPARTMENTAL USE ONLY ± Fu;Kzr Ds Fy, Ugha NOT for EXPORT

WARD 62-S, HAUZ KHAS izfrcaf/kr RESTRICTED dsoy foHkkxh; Á;®x gsrq FOR DEPARTMENTAL USE ONLY ± fu;kZr ds fy, ugha NOT FOR EXPORT SOUTH EXTN. WARDS AS SEEN WITHIN AC-43 (MALVIYA NAGAR) SOUTH EXTENSION PART - II ANSARI NAGAR EAST MASJID MOTH J A IN M UDAY PARK GAUTAM NAGAR A R 62-S_HAUZ KHAS GREEN PARK RWA OFFICE G N. C.R INDIA 61-S_SAFDARJUNG ENCLAVE NEETI BAGH NEW YUSUF SARAI GULMOHAR ENCLAVE GULMOHAR PARK BLOCK B GULMOHAR PARK 63-S_MALVIYA NAGAR DELHI JAL BOARD HAUZ KHAS BLOCK Z HAUZ KHAS BLOCK Y LEGEND HAUZ KHAS BLOCK A [ [ [ Railway Line HAUZ KHAS BLOCK X Bank AUDITORIUM mm HAUZ KHAS BLOCK M C College Canal SIRI INSTITUTIONAL AREA Bus Stop River G R A WARD NO.62-S ñ Auditorium M Storm Water O HAUZ KHAS D Fire Station N Pond I HAUZ KHAS BLOCK C B : O PWD OFFICE =( Metro Station R Sub Locality U A P MAYFAIR GARDEN Bus Terminal Locality E N PADMINI ENCLAVE G A Health Centre L Play Ground E C I HAUZ KHAS ENCLAVE BLOCK K Cats Ambulance V Stadium R E BSES OFFICE S 7m ¯ Community Center Garden Parks HAUZ KHAS k Government Office I I T GATE Ward Boundary Accident Trauma Center Roads AC Boundary SARVAPRIYA VIHAR KALU SARAI BSES OFFICE 310 0 310 620 SARVAPRIYA VIHAR Meters VIJAY MANDAL ENCLAVE BHAVISHYA NIDHI ENCLAVE 1:16,000 MALVIYA NAGAR BLOCK A For further details about this map , please contact BEGAMPUR VILLAGE ADHCHINI Geospatial Delhi Limited SARVODAYA ENCLAVE SARVODYA ENCLAVE SARVODAYA ENCLAVE BLOCK B ADARSH FARM Website : www.gsdl.org.in Disclaimer: Reproduction in whole or part by any means is prohibited without written permission of Geospatial Delhi Limited and State Election Commission Delhi. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Jahanpanah Part of the Sarai Shahji Village As a Place for Travellers to Stay

CORONATION PARK 3. SARAI SHAHJI MAHAL 5. KHARBUZE KA GUMBAD a walk around The Sarai Shahji Mahal is best approached from the main Geetanjali This is an interesting, yet bizarre little structure, Road that cuts through Malviya Nagar rather than from the Begumpur located within the premises of a Montessori village. The mahal (palace) and many surrounding buildings were school in the residential neighbourhood of Jahanpanah part of the Sarai Shahji village as a place for travellers to stay. Of the Delhi Metro Sadhana Enclave in Malviya Nagar. It is essentially Route 6 two Mughal buildings, the fi rst is a rectangular building with a large a small pavilion structure and gets its name from Civil Ho Ho Bus Route courtyard in the centre that houses several graves. Towards the west, is the tiny dome, carved out of solid stone and Lines a three-bay dalan (colonnaded verandah) with pyramidal roofs, which placed at its very top, that has the appearance of Heritage Route was once a mosque. a half-sliced melon. It is believed that Sheikh The other building is a slightly more elaborate apartment in the Kabir-ud-din Auliya, buried in the Lal form of a tower. The single room is entered through a set of three Gumbad spent his days under this doorways set within a large arch. The noticeable feature here is a dome and the night in the cave located SHAHJAHANABAD Red Fort balcony-like projection over the doorway which is supported by below it. The building has been dated carved red sandstone brackets. -

India Architecture Guide 2017

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Zanskar Geologically, the Zanskar Range is part of the Tethys Himalaya, an approximately 100-km-wide synclinorium. Buddhism regained its influence Lungnak Valley over Zanskar in the 8th century when Tibet was also converted to this ***** Zanskar Desert ཟངས་དཀར་ religion. Between the 10th and 11th centuries, two Royal Houses were founded in Zanskar, and the monasteries of Karsha and Phugtal were built. Don't miss the Phugtal Monastery in south-east Zanskar. Zone 2: Punjab Built in 1577 as the holiest Gurdwara of Sikhism. The fifth Sikh Guru, Golden Temple Rd, Guru Arjan, designed the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) to be built in Atta Mandi, Katra the centre of this holy tank. The construction of Harmandir Sahib was intended to build a place of worship for men and women from all walks *** Golden Temple Guru Ram Das Ahluwalia, Amritsar, Punjab 143006, India of life and all religions to come and worship God equally. The four entrances (representing the four directions) to get into the Harmandir ਹਰਿਮੰਦਿ ਸਾਰਹਬ Sahib also symbolise the openness of the Sikhs towards all people and religions. Mon-Sun (3-22) Near Qila Built in 2011 as a museum of Sikhism, a monotheistic religion originated Anandgarh Sahib, in the Punjab region. Sikhism emphasizes simran (meditation on the Sri Dasmesh words of the Guru Granth Sahib), that can be expressed musically *** Virasat-e-Khalsa Moshe Safdie Academy Road through kirtan or internally through Nam Japo (repeat God's name) as ਰਿਿਾਸਤ-ਏ-ਖਾਲਸਾ a means to feel God's presence. -

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

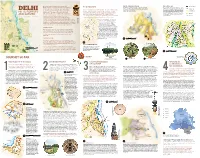

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France.