Barry Strauss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizens and Soldiers in the Siege of Yorktown

Citizens and Soldiers in the Siege of Yorktown Introduction During the summer of 1781, British general Lord Cornwallis occupied Yorktown, Virginia, the seat of York County and Williamsburg’s closest port. Cornwallis’s commander, General Sir Henry Clinton, ordered him to establish a naval base for resupplying his troops, just after a hard campaign through South and North Carolina. Yorktown seemed the perfect choice, as at that point, the river narrowed and was overlooked by high bluffs from which British cannons could control the river. Cornwallis stationed British soldiers at Gloucester Point, directly opposite Yorktown. A British fleet of more than fifty vessels was moored along the York River shore. However, in the first week of September, a French fleet cut off British access to the Chesapeake Bay, and the mouth of the York River. When American and French troops under the overall command of General George Washington arrived at Yorktown, Cornwallis pulled his soldiers out of the outermost defensive works surrounding the town, hoping to consolidate his forces. The American and French troops took possession of the outer works, and laid siege to the town. Cornwallis’s army was trapped—unless General Clinton could send a fleet to “punch through” the defenses of the French fleet and resupply Yorktown’s garrison. Legend has it that Cornwallis took refuge in a cave under the bluffs by the river as he sent urgent dispatches to New York. Though Clinton, in New York, promised to send aid, he delayed too long. During the siege, the French and Americans bombarded Yorktown, flattening virtually every building and several ships on the river. -

The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War Robert Sloane Boston Univeristy School of Law

Boston University School of Law Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Faculty Scholarship 8-22-2013 Book Review of The eV rdict of Battle: The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War Robert Sloane Boston Univeristy School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the International Humanitarian Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Robert Sloane, Book Review of The Verdict of Battle: The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War, No. 13-29 Boston University School of Law, Public Law Research Paper (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/24 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW OF JAMES Q. WHITMAN, THE VERDICT OF BATTLE: THE LAW OF VICTORY AND THE MAKING OF MODERN WAR (2012) Boston University School of Law Worrking Paper No. 13-39 (August 22, 2013) Robert D. Sloane Boston University Schoool of Law This paper can be downloaded without charge at: http://www.bu.edu/law/faculty/scholarship/workingpapers/2013.html The Verdict of Battle: The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War. By James Q. Whitman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012. Pp. vii, 323. Index. For evident reasons, scholarship on the law of war has been a growth industry for the past two decades. -

A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations from 1941 to the Present

CRM D0006297.A2/ Final July 2002 Charting the Pathway to OMFTS: A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations From 1941 to the Present Carter A. Malkasian 4825 Mark Center Drive • Alexandria, Virginia 22311-1850 Approved for distribution: July 2002 c.. Expedit'onaryyystems & Support Team Integrated Systems and Operations Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N0014-00-D-0700. For copies of this document call: CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 0 2002 The CNA Corporation Contents Summary . 1 Introduction . 5 Methodology . 6 The U.S. Marine Corps’ new concept for forcible entry . 9 What is the purpose of amphibious warfare? . 15 Amphibious warfare and the strategic level of war . 15 Amphibious warfare and the operational level of war . 17 Historical changes in amphibious warfare . 19 Amphibious warfare in World War II . 19 The strategic environment . 19 Operational doctrine development and refinement . 21 World War II assault and area denial tactics. 26 Amphibious warfare during the Cold War . 28 Changes to the strategic context . 29 New operational approaches to amphibious warfare . 33 Cold war assault and area denial tactics . 35 Amphibious warfare, 1983–2002 . 42 Changes in the strategic, operational, and tactical context of warfare. 42 Post-cold war amphibious tactics . 44 Conclusion . 46 Key factors in the success of OMFTS. 49 Operational pause . 49 The causes of operational pause . 49 i Overcoming enemy resistance and the supply buildup. -

The Crucial Development of Heavy Cavalry Under Herakleios and His Usage of Steppe Nomad Tactics Mark-Anthony Karantabias

The Crucial Development of Heavy Cavalry under Herakleios and His Usage of Steppe Nomad Tactics Mark-Anthony Karantabias The last war between the Eastern Romans and the Sassanids was likely the most important of Late Antiquity, exhausting both sides economically and militarily, decimating the population, and lay- ing waste the land. In Heraclius: Emperor of Byzantium, Walter Kaegi, concludes that the Romaioi1 under Herakleios (575-641) defeated the Sassanian forces with techniques from the section “Dealing with the Persians”2 in the Strategikon, a hand book for field commanders authored by the emperor Maurice (reigned 582-602). Although no direct challenge has been made to this claim, Trombley and Greatrex,3 while inclided to agree with Kaegi’s main thesis, find fault in Kaegi’s interpretation of the source material. The development of the katafraktos stands out as a determining factor in the course of the battles during Herakleios’ colossal counter-attack. Its reforms led to its superiority over its Persian counterpart, the clibonarios. Adoptions of steppe nomad equipment crystallized the Romaioi unit. Stratos4 and Bivar5 make this point, but do not expand their argument in order to explain the victory of the emperor over the Sassanian Empire. The turning point in its improvement seems to have taken 1 The Eastern Romans called themselves by this name. It is the Hellenized version of Romans, the Byzantine label attributed to the surviving East Roman Empire is artificial and is a creation of modern historians. Thus, it is more appropriate to label them by the original version or the Anglicized version of it. -

300: Greco-Persian Wars 300: the Persian Wars — Rule Book

300: Greco-Persian Wars 300: The Persian Wars — Rule book 1.0 Introduction Illustration p. 2 City "300" has as its theme the war between Persia and Name Greece which lasted for 50 years from the Ionian Food Supply Revolt in 499 BC to the Peace of Callias in 449 BC Road One player plays the Greek army, based around Blue Ear of Wheat = Supply city for the Greek Athens and Sparta, and the other the Persian army. Army During these fifty years launched three expeditions ■ Red = Important city for the Persian army to Greece but in the game they may launch up to Athens is a port five. Corinth is not a port Place name (does not affect the game) 2.0 Components 2.1.4 Accumulated Score Track: At the end of The game is played using the following elements. each expedition, note the difference in score between the two sides. At the end of the game, the 2.1 Map player who leads on accumulated score even by one point, wins the game. If the score is 0, the result is a The map covers Greece and a portion of Asia Minor draw. in the period of the Persian Wars. 2.1.5 Circles of Death/Ostracism: These contain 2.1.1 City: Each box on the map is a city, the images of individuals who died or were containing the following information: ostracised in the course of the game. When this • Name: the name of the city. occurs, place an army or fleet piece in the indicated • Important City: the red cities are important for the circle. -

The Multilingual Urban Environment of Achaemenid Sardis

s Ls The multilingual urban environment of Achaemenid Sardis Maria Carmela Benvenuto - Flavia Pompeo - Marianna Pozza Abstract Achaemenid Sardis provides a challenging area of research regarding multilingual- ism in the past. Indeed, Sardis was one of the most important satrapal capitals of the Persian Empire both from a political and commercial point of view, playing a key diplomatic role in Greek-Persian relations. Different ethnic groups lived in, or often passed through the city: Lydians, Greeks, Persians and, possibly, Carians and Aramaic- speaking peoples. Despite this multilingual situation, the epigraphic records found at Sardis, or which relate to the city in some way, are scarce, especially when compared to other areas of Asia Minor. The aim of our research – the preliminary results of which are presented here – is to describe the linguistic repertoire of Achaemenid Sardis and the role played by non-epichoric languages. A multi-modal approach will be adopted and particular attention will be paid to the extra-linguistic (historical, social and cul- tural) context. Keywords: Achaemenid Sardis, Aramaic, Greek, Lydian, linguistic repertoire. 1. Introduction This study examines the interrelation between identity and linguistic and socio-cultural dynamics in the history of Achaemenid Lydia. Specifi- cally, the aim of our research is to describe the linguistic repertoire of Ach- aemenid Sardis and the role played by non-epichoric languages within this context, adopting an approach which combines both linguistic and non- linguistic evidence. Given the richness and the complexity of the topic, the present work focuses on the preliminary results of our analysis1. To this end, the paper is organized as follows: section 2 is devoted to a brief historical introduction while section 3 considers methodological issues. -

The Persian Wars: Ionian Revolt the Ionian Revolt, Which Began in 499

The Persian Wars: Ionian Revolt The Ionian Revolt, which began in 499 B.C. marked the beginning of the Greek-Persian wars. In 546 B.C. the Persians had conquered the wealthy Greek settlements in Ionia (Asia Minor). The Persians took the Ionians’ farmland and harbors. They forced the Ionians to pay tributes (the regular payments of goods). The Ionians also had to serve in the Persian army. The Ionians knew they could not defeat the Persians by themselves, so they asked mainland Greece for help. Athens sent soldiers and a small fleet of ships. Unfortunately for the Ionians, the Athenians went home after their initial success, leaving the small Ionian army to fight alone. In 493 B.C. the Persian army defeated the Ionians. To punish the Ionians for rebelling, the Persians destroyed the city of Miletus. They may have sold some of tis people into slavery. The Persian Wars: Battle of Marathon After the Ionian Revolt, the Persian King Darius decided to conquer the city-states of mainland Greece. He sent messengers to ask for presents of Greek earth and water as a sign that the Greeks agreed to accept Persian rule. But the Greeks refused. Darius was furious. In 490 B.C., he sent a large army of foot soldiers and cavalry (mounted soldiers) across the Aegean Sea by boat to Greece. The army assembled on the pain of Marathon. A general named Miltiades (Mill-te-ah-deez) convinced the other Greek commanders to fight the Persians at Marathon. In need of help, the Athenians sent a runner named Pheidippides (Fa-dip-e-deez) to Sparta who ran for two days and two nights. -

The Late Bronze–Early Iron Transition: Changes in Warriors and Warfare and the Earliest Recorded Naval Battles

The Late Bronze–Early Iron Transition: Changes in Warriors and Warfare and the Earliest Recorded Naval Battles The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Emanuel, Jeffrey P. 2015. "The Late Bronze–Early Iron Transition: Changes." In Warriors and Warfare and the Earliest Recorded Naval Battles. Ancient Warfare: Introducing Current Research, ed. by G. Lee, H. Whittaker, and G. Wrightson, 191-209. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Published Version http://www.cambridgescholars.com/ancient-warfare Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:26770940 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Ancient Warfare Ancient Warfare: Introducing Current Research, Volume I Edited by Geoff Lee, Helene Whittaker and Graham Wrightson Ancient Warfare: Introducing Current Research, Volume I Edited by Geoff Lee, Helene Whittaker and Graham Wrightson This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Geoff Lee, Helene Whittaker, Graham Wrightson and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

The Persian Empire

3 The Persian Empire MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES BUILDING By governing with Leaders today try to follow the • Cyrus • satrap tolerance and wisdom, the Persian example of tolerance • Cambyses • Royal Road Persians established a well- and wise government. • Darius • Zoroaster ordered empire that lasted for 200 years. SETTING THE STAGE The Medes, along with the Chaldeans and others, helped to overthrow the Assyrian Empire in 612 B.C. The Medes marched to Nineveh from their homeland in the area of present-day northern Iran. Meanwhile, the Medes’ close neighbor to the south, Persia, began to expand its horizons and territorial ambitions. The Rise of Persia The Assyrians employed military force to control a vast empire. In contrast, the Persians based their empire on tolerance and diplomacy. They relied on a strong TAKING NOTES military to back up their policies. Ancient Persia included what today is Iran. Use the graphic organizer online to take notes The Persian Homeland Indo-Europeans first migrated from Central Europe on the similarities and and southern Russia to the mountains and plateaus east of the Fertile Crescent differences between around 1000 B.C. This area extended from the Caspian Sea in the north to the Cyrus and Darius. Persian Gulf in the south. (See the map on page 101.) In addition to fertile farm- land, ancient Iran boasted a wealth of minerals. These included copper, lead, gold, silver, and gleaming blue lapis lazuli. A thriving trade in these minerals put the settlers in contact with their neighbors to the east and the west. -

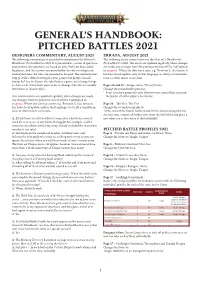

General's Handbook: Pitched Battles 2021

® GENERAL’S HANDBOOK: PITCHED BATTLES 2021 DESIGNERS COMMENTARY, AUGUST 2021 ERRATA, AUGUST 2021 The following commentary is intended to complement the General’s The following errata correct errors in the General’s Handboook: Handbook: Pitched Battles 2021. It is presented as a series of questions Pitched Battles 2021. The errata are updated regularly; when changes and answers; the questions are based on ones that have been asked are made, any changes from the previous version will be highlighted by players, and the answers are provided by the rules writing team in magenta. Where the date has a note, e.g. ‘Revision 2’, this means it and explain how the rules are intended to be used. The commentaries has had a local update, only in that language, to clarify a translation help provide a default setting for your games, but players should issue or other minor correction. always feel free to discuss the rules before a game, and change things as they see fit if they both want to do so (changes like this are usually Pages 24 and 25 – Savage Gains, Victory Points referred to as ‘house rules’). Change the second bullet point to: ‘- Score 2 victory points for each objective you control that is not on Our commentaries are updated regularly; when changes are made, the border of either player’s territories.’ any changes from the previous version will be highlighted in magenta. Where the date has a note, e.g. ‘Revision 2’, this means it Page 36 – The Vice, The Vice has had a local update, only in that language, to clarify a translation Change the second paragraph to: issue or other minor correction. -

Ancient History

ANCIENT HISTORY 500 – 440 BC Evaluate the contribution of Miltiades and Themistocles to the Greek victory over the Persians from 490 to 479 BC. During the Persian Wars a number of personalities arose to challenge the threat from across the Aegean, all of them with personal motivations, strategies, diplomatic initiatives and policies. Greek politics were tense at the time of the Persian wars as Herodotus reports,“Among the Athenian commanders opinion was divided”. Some of the prominent personalities of both Athens and Sparta include Aristides, Themistocles, Leonidas, Miltiades and Pausanius. However it was Miltiades and Themistocles that made the greatest contribution to Greek Victory. Both Miltiades and Themistocles used their prior experience as well as thought out tactics to outplay the ‘unbeatable’ Persian army. Separately, these two personalities successfully led the Greeks to victory through the battles of Marathon and Salamis, as well as a number of significant catalysts. Despite this, the contribution of Themistocles to the Persian Wars may have been greater than that of Miltiades due to the lasting effect his changes made to the entire war effort but this may have been due to the length of their time in power. Miltiades was not always respected by his Athenian counterparts as previous to the Persian Wars he had acted as vassal to the Persian King, Darius I. The Ionian Revolt proved a great turning point for many Greeks who were under Persian influence. Miltiades joined the revolt and returned to Athens but was imprisoned for the crime of tyranny with the sentence of death. However, he was able to prove himself anti-Persian and was released. -

The Battle of Salamis Curtis Kelly

Level 3 - 7 The Battle of Salamis Curtis Kelly Summary This book is about how the Battle of Salamis changed the course of history, both for Greece and the West. Contents Before Reading Think Ahead ........................................................... 2 Vocabulary .............................................................. 3 During Reading Comprehension ...................................................... 5 After Reading Think About It ........................................................ 8 Before Reading Think Ahead Look at the pictures and answer the questions. arrow warrior fleet oar sailor 1. How does a boat move in the water? 2. Who works on boats? 3. What was a weapon used during ancient war times? 4. Who fights in battles? 2 World History Readers Before Reading Vocabulary A Read and match. 1. a. army Did you eat the cake? 2. b. strait Yes! 3. c. hilltop 4. d. backwards 5. e. captain 6. f. flee 7. g. truth 8. h. smash The Battle of Salamis 3 Before Reading B Write the word for each definition. informer conquer invade brave victory 1. to attack a country to take its land 2. the act of winning a fight or competition 3. fearless or courageous; ready to face danger 4. to take control of a country or defeat people in a war 5. a person who gives information in secret C Choose the word that means about the same as the underlined words. 1. A large navy is very strong. a. brave b. truthful c. weak d. powerful 2. If the boat doesn’t turn now, it will hit the iceberg. a. throw b. catch c. ram d. fall 3. It is not very easy to trick the wise leader.