Mirror & Pomegranate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

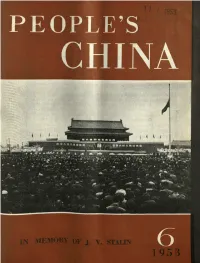

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

THE ARMENIAN Mirrorc SPECTATOR Since 1932

THE ARMENIAN MIRRORc SPECTATOR Since 1932 Volume LXXXXI, NO. 37, Issue 4679 APRIL 3, 2021 $2.00 Third Dink Murder Trial Verdicts Issued, Dink Family Issues Statement ISTANBUL (MiddleEastEye, Bianet, Dink Fami- ly) — An Istanbul court issued six sentences of life imprisonment and 23 jail terms, while 33 defendants were acquitted on March 26 in the third court case concerning the January 2007 Hrant Dink murder. One individual died during the trial, leading to charges against him being dropped. Among those sentenced were former police chiefs and security officials. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) Representative to Turkey Erol Önderoğlu commented: “The Hrant Dink case is not over. This is the third trial and it does not comprise behind-the-scenes actors who threatened him with a statement, threw him before vi- olent groups as an object of hate or failed to act so that he would get killed. As a matter of fact, the attorneys of the Dink family made an application to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) last year as they could A cargo plane carrying COVID-19 Vaccines lands in Armenia. not have over 20 officials put on trial.” The 17-year-old Ogun Samast was convicted of the crime in 2011 but it was clear that he could not have Large Shipment of AstraZeneca carried out this alone. The first court ruling was issued Vaccine Arrives in Armenia By Raffi Elliott The shipment, which was initially Agency (EMA). Special to the Mirror-Spectator expected in mid-February, had been At a press conference held in Yere- delayed due to disruptions in the glob- van on Monday, Deputy Director of YEREVAN — A Swiss Air cargo al supply chain. -

Understanding Screenwriting'

Course Materials for 'Understanding Screenwriting' FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 Evan Wm. Cameron Professor Emeritus Senior Scholar in Screenwriting Graduate Programmes, Film & Video and Philosophy York University [Overview, Outline, Readings and Guidelines (for students) with the Schedule of Lectures and Screenings (for private use of EWC) for an extraordinary double-weighted full- year course for advanced students of screenwriting, meeting for six hours weekly with each term of work constituting a full six-credit course, that the author was permitted to teach with the Graduate Programme of the Department of Film and Video, York University during the academic years 2001-2002 and 2002-2003 – the most enlightening experience with respect to designing movies that he was ever permitted to share with students.] Overview for Graduate Students [Preliminary Announcement of Course] Understanding Screenwriting FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 FA/FILM 4501 A 6.0 & FA/FILM 4501 B 6.0 Understanding Screenwriting: the Studio and Post-Studio Eras Fall/Winter, 2002-2003 Tuesdays & Thursdays, Room 108 9:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. Evan William Cameron We shall retrace within these courses the historical 'devolution' of screenwriting, as Robert Towne described it, providing advanced students of writing with the uncommon opportunity to deepen their understanding of the prior achievement of other writers, and to ponder without illusion the nature of the extraordinary task that lies before them should they decide to devote a part of their life to pursuing it. During the fall term we shall examine how a dozen or so writers wrote within the studio system before it collapsed in the late 1950s, including a sustained look at the work of Preston Sturges. -

EUROPE a Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania

EUROPE A Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania o The country's largest museum. It was opened on 28 October 1981 and is 27,000 square meters in size, while 18,000 square meters are available for expositions. The National Historical Museum includes the following pavilions: Pavilion of Antiquity, Pavilion of the Middle Ages, Pavilion of Renaissance, Pavilion of Independence, Pavilion of Iconography, Pavilion of the National Liberation Antifascist War, Pavilion of Communist Terror, and Pavilion of Mother Teresa. • Et'hem Bey Mosque – Tirana, Albania o The Et’hem Bey Mosque is located in the center of the Albanian capital Tirana. Construction was started in 1789 by Molla Bey and it was finished in 1823 by his son Ethem Pasha (Haxhi Ethem Bey), great- grandson of Sulejman Pasha. • Mount Dajt – Tirana, Albania o Its highest peak is at 1,613 m. In winter, the mountain is often covered with snow, and it is a popular retreat to the local population of Tirana that rarely sees snow falls. Its slopes have forests of pines, oak and beech. Dajti Mountain was declared a National Park in 1966, and has since 2006 an expanded area of about 29,384 ha. It is under the jurisdiction and administration of Tirana Forest Service Department. • Skanderbeg Square – Tirana, Albania o Skanderbeg Square is the main plaza of Tirana, Albania named in 1968 after the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg. A Skanderbeg Monument can be found in the plaza. • Skanderbeg Monument – Skanderberg Square, Tirana, Albania o The monument in memory of Skanderbeg was erected in Skanderbeg Square, Tirana. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

From Proletarian Internationalism to Populist

from proletarian internationalism to populist russocentrism: thinking about ideology in the 1930s as more than just a ‘Great Retreat’ David Brandenberger (Harvard/Yale) • [email protected] The most characteristic aspect of the newly-forming ideology... is the downgrading of socialist elements within it. This doesn’t mean that socialist phraseology has disappeared or is disappearing. Not at all. The majority of all slogans still contain this socialist element, but it no longer carries its previous ideological weight, the socialist element having ceased to play a dynamic role in the new slogans.... Props from the historic past – the people, ethnicity, the motherland, the nation and patriotism – play a large role in the new ideology. –Vera Aleksandrova, 19371 The shift away from revolutionary proletarian internationalism toward russocentrism in interwar Soviet ideology has long been a source of scholarly controversy. Starting with Nicholas Timasheff in 1946, some have linked this phenomenon to nationalist sympathies within the party hierarchy,2 while others have attributed it to eroding prospects for world This article builds upon pieces published in Left History and presented at the Midwest Russian History Workshop during the past year. My eagerness to further test, refine and nuance this reading of Soviet ideological trends during the 1930s stems from the fact that two book projects underway at the present time pivot on the thesis advanced in the pages that follow. I’m very grateful to the participants of the “Imagining Russia” conference for their indulgence. 1 The last line in Russian reads: “Bol’shuiu rol’ v novoi ideologii igraiut rekvizity istoricheskogo proshlogo: narod, narodnost’, rodina, natsiia, patriotizm.” V. -

Collector Coins of the Republic of Armenia 2012

CENTRAL BANK OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA 2012 YEREVAN 2013 Arthur Javadyan Chairman of the Central Bank of Armenia Dear reader The annual journal "Collector Coins of the Republic of Armenia 2012" presents the collector coins issued by the Central Bank of Armenia in 2012 on occasion of important celebrations and events of the year. 4 The year 2012 was full of landmark events at both international and local levels. Armenia's capital Yerevan was proclaimed the 12th International Book 2012 Capital, and in the timespan from April 22, 2012 to April 22, 2013 large-scale measures and festivities were held not only in Armenia but also abroad. The book festival got together the world's writers, publishers, librarians, book traders and, in general, booklovers everywhere. The year saw a great diversity of events which were held in cooperation with other countries. Those events included book exhibitions, international fairs, contests ("Best Collector Coins CENTRAL BANK OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA Literary Work", "Best Thematic Posters"), a variety of projects ("Give-A-Book Day"), workshops, and film premieres. The Central Bank of Armenia celebrated the book festival by issuing the collector coin "500th Anniversary of Armenian Book Printing". In 2012, the 20th anniversaries of formation of Armenian Army and liberation of Shushi were celebrated with great enthusiasm. On this occasion, the Central Bank of Armenia issued the gold and silver coins "20th Anniversary of Formation of Armenian Army" and the gold coin "20th Anniversary of Liberation of Shushi". The 20th anniversary of signing Collective Security Treaty and the 10 years of the Organization of Treaty were celebrated by issuing a collector coin dedicated to those landmark events. -

Print This Article

Number 2301 Alexander Kolchinsky Stalin on Stamps and other Philatelic Materials: Design, Propaganda, Politics Number 2301 ISSN: 2163-839X (online) Alexander Kolchinsky Stalin on Stamps and other Philatelic Materials: Design, Propaganda, Politics This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This site is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program, and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Alexander Kolchinsky received his Ph. D. in molecular biology in Moscow, Russia. During his career in experimental science in the former USSR and later in the USA, he published more than 40 research papers, reviews, and book chapters. Aft er his retirement, he became an avid collector and scholar of philately and postal history. In his articles published both in Russia and in the USA, he uses philatelic material to document the major historical events of the past century. Dr. Kolchinsky lives in Champaign, Illinois, and is currently the Secretary of the Rossica Society of Russian Philately. No. 2301, August 2013 2013 by Th e Center for Russian and East European Studies, a program of the Uni- versity Center for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh ISSN 0889-275X (print) ISSN 2163-839X (online) Image from cover: Stamps of Albania, Bulgaria, People’s Republic of China, German Democratic Republic, and the USSR reproduced and discussed in the paper. The Carl Beck Papers Publisher: University Library System, University of Pittsburgh Editors: William Chase, Bob Donnorummo, Robert Hayden, Andrew Konitzer Managing Editor: Eileen O’Malley Editorial Assistant: Tricia J. -

“Building Bridges, Breaking the Walls: Managing Refugee Crisis in Europe” 2-Stage Project TRAINING COURSE & STUDY VISIT

“Building Bridges, Breaking the Walls: Managing Refugee Crisis in Europe” 2-Stage Project TRAINING COURSE & STUDY VISIT Basic information What: Training Course Title: Building Bridges, Breaking the Walls: Managing Refugee Crisis in Europe Venues and dates: Training Course: 20-28 November (including travel days), Yerevan, Armenia Study Visit: February (days will be confirmed), Stockholm, Sweden Participating Countries: Armenia, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Italy, Moldova, Romania, Ukraine, Denmark, Turkey, Czech Republic, Greece, Germany, Georgia, Portugal Idea, theme and objectives Structure The project is intended for 32 youth workers, youth educators, members of civil society organizations from 15 European Union and the Neighboring countries who are ready to actively fight against radicalization, discrimination and intolerance against refugees and migrants in their countries and who want to transfer the knowledge they gained in the project to the youth in their organizations and countries. NOTE! To ensure a long term impact we will involve same 36 youth workers in both activities of the project. Objectives of the Activity: The Training Course (Armenia) and the Study Visit (Sweden) have the following main objectives: To provide conceptual framework on the notions of emigration, immigration, integration and multiculturalism to 36 youth workers from different European countries; To analyze the emigration and immigration situation in participating countries and to find out the causes of migration, namely push and pull factors; To discuss -

MONTHLY GUIDE April 2015 | ISSUE 69 | South Africa / Zimbabwe / Zambia

MONTHLY GUIDE APRIL 2015 | ISSUE 69 | SOUTH AFRICA / ZIMBABWE / ZAMBIA Sophia: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow Vanilla and Chocolate School Is Over Fedez And more EUROCHANNEL GUIDE | MAY 2015 | 1 HOLLYWOOD BROOKLYN MAY 29 - JUNE 7 2015 ILLUMINATE EDITION Venues: WYTHE HOTEL // WINDMILL STUDIOS NYC NITEHAWK CINEMA // MADE IN NY MEDIA CENTER BY IFP 2 | EUROCHANNEL GUIDE | MAY 2015 | MONTHLY GUIDE| MAY 2015 | ISSUE 70 Sophia: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow following our five successful editions, this month, we present the lineup of our much beloved month on Eurochannel, a unique occasion in the year to appreciate Italy beyond stereotypes and mainstream cinema from Hollywood, and to be delighted with the greatest cinematic productions from “The Boot of Europe.” Welcome to the 6th Edition of the Italian Month: Viva il Cinema! Vanilla and Chocolate These enchanting movies gather a number of A-list actors offering us the performances of a lifetime. This month, you can enjoy the talent of Italian top-billed stars such as comedy legend Diego Abatantuono, Maria Grazia Cucinotta (The World Is Not Enough, Il Postino: The Postman, The Rite, The Sopranos, The Simpsons). But beyond awards and festivals, the films and documentaries present in this edition offer a common thing: the desire to overcome difficulties and to offer hope and encouragement to pursue our dreams. In films such as School Is Over, we witness how a conflicted teenager is rescued by his Fedez teachers, who also save their marriage in the process. Legends also teach us the importance of perseverance despite the tribulations that may arise. Documentaries such as Sophia: Yesterday, Table of Today, and Tomorrow, and Tonino Guerra, A Poet in the Movies reveal the contents dreams, hurdles, passions and setbacks of Italian cinema legends Sophia Loren and Tonino Guerra. -

East Asians in Soviet Intelligence and the Chinese-Lenin School of the Russian Far East

East Asians in Soviet Intelligence and the Chinese-Lenin School of the Russian Far East Jon K. Chang Abstract1 This study focuses on the Chinese-Lenin School (also the acronym CLS) and how the Soviet state used the CLS and other tertiary institutions in the Russian Far East to recruit East Asians into Soviet intelligence during the 1920s to the end of 1945. Typically, the Chinese and Korean intelligence agents of the USSR are presented with very few details with very little information on their lives, motivations and beliefs. This article will attempt to bridge some of this “blank spot” and will cover the biographies of several East Asians in the Soviet intelligence services, their raison d’être, their world view(s) and motivations. The basis for this new study is fieldwork, interviews and photographs collected and conducted in Central Asia with the surviving relatives of six East Asian former Soviet intelligence officers. The book, Chinese Diaspora in Vladivostok, Second Edition [Kitaiskaia diaspora vo Vladivostoke, 2-е izdanie] which was written in Russian by two local historians from the Russian Far East also plays a major role in this study’s depth, revelations and conclusions.2 Methodology: (Long-Term) Oral History and Fieldwork My emphasis on “oral history” in situ is based on the belief that the state archives typically chronicle and tell a history in which the state, its officials and its institutions are the primary actors and “causal agents” who create a powerful, actualized people from the common clay of workers, peasants and sometimes, draw from society’s more marginalized elements such as vagabonds and criminals. -

Goldman Nationallly Informed Full Draft 2

Nationally Informed: The Politics of National Minority Music during Late Stalinism Leah Goldman, Reed College Introduction After consolidating its control over the former Russian Empire, the new Soviet state endeavored to distinguish itself from its imperial predecessor by demonstrating its support for the panoply of national minorities now under its jurisdiction. Imperial Russia had sought to Russify the peoples of its western borderlands and exert colonial dominance over those in the Caucasus and Central Asia. By contrast, Soviet officials made a concert- ed effort to celebrate the Union’s internal diversity and enable all national cultures to flourish. This strategy took a variety of forms, from creation of nationality-based autono- mous regions and republics, to promotion of titular nationalities into administrative posts through the policy of korenizatsiia, to establishment of indigenous-language educational and media institutions.1 It also had a profound effect on the official approach to cultural production, not least in the area of music. For Soviet leaders, supporting the musical cultures of the national minorities meant both granting a new sense of value to existing folk traditions and bringing those traditions into the present by creating a repertoire of folk-inflected operas, symphonies, and chamber works for each minority group. These dual processes got underway in the 1930s, after the Soviet Union’s internal borders were settled and the militant “proletarian- ism” of the Cultural Revolution gave way to the more staid, ethnocentric atmosphere of the Second Five Year Plan.2 As Marina Frolova-Walker has detailed, Russian composers initially took the lead. Employing the ethos and methods of 19th-century Romantic nation- alism, they made ethnographic collections of indigenous folksongs and wove them into new symphonic and operatic works.3 This literature was intended only as a placeholder, however.