Book Review: What Is Mathematics? an Elementary Approach to Ideas and Methods, Volume 48, Number 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

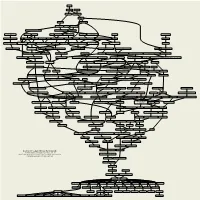

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction To

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Springer-V erlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH Richard Courant • Fritz John Introd uction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Reprint of the 1989 Edition Springer Originally published in 1965 by Interscience Publishers, a division of John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Reprinted in 1989 by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. Mathematics Subject Classification (1991): 26-XX, 26-01 Cataloging in Publication Data applied for Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Courant, Richard: Introduction to calcu1us and analysis / Richard Courant; Fritz John.- Reprint of the 1989 ed.- Berlin; Heidelberg; New York; Barcelona; Hong Kong; London; Milan; Paris; Singapore; Tokyo: Springer (Classics in mathematics) VoL 1 (1999) ISBN 978-3-540-65058-4 ISBN 978-3-642-58604-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-58604-0 Photograph of Richard Courant from: C. Reid, Courant in Gottingen and New York. The Story of an Improbable Mathematician, Springer New York, 1976 Photograph of Fritz John by kind permission of The Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York ISSN 1431-0821 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved. whether the whole or part of the material is concemed. specifically the rights of trans1ation. reprinting. reuse of illustrations. recitation. broadcasting. reproduction on microfilm or in any other way. and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted onlyunder the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9.1965. in its current version. and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are Iiable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

An Annotated Bibliography on the Foundations of Statistical Inference

• AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE FOUNDATIONS OF STATISTICAL INFERENCE • by Stephen L. George A cooperative effort between the Department of Experimental • Statistics and the Southeastern Forest Experiment Station Forest Service U.S.D.A. Institute of Statistics Mimeograph Series No. 572 March 1968 The Foundations of Statistical Inference--A Bibliography During the past two hundred years there have been many differences of opinion on the validity of certain statistical methods and no evidence that ,. there will be any general agreement in the near future. Also, despite attempts at classification of particular approaches, there appears to be a spectrum of ideas rather than the existence of any clear-cut "schools of thought. " The following bibliography is concerned with the continuing discussion in the statistical literature on what may be loosely termed ''the foundations of statistical inference." A major emphasis is placed on the more recent works in this area and in particular on recent developments in Bayesian analysis. Invariably, a discussion on the foundations of statistical inference leads one to the more general area of scientific inference and eventually to the much more general question of inductive inference. Since this bibliography is intended mainly for those statisticians interested in the philosophical foundations of their chosen field, and not for practicing philosophers, the more general discussion of inductive inference was deliberately de-emphasized with the exception of several distinctive works of particular relevance to the statistical problem. Throughout, the temptation to gather papers in the sense of a collector was resisted and most of the papers listed are of immediate relevance to the problem at hand. -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Emigration Of

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 51/2011 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2011/51 Emigration of Mathematicians and Transmission of Mathematics: Historical Lessons and Consequences of the Third Reich Organised by June Barrow-Green, Milton-Keynes Della Fenster, Richmond Joachim Schwermer, Wien Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze, Kristiansand October 30th – November 5th, 2011 Abstract. This conference provided a focused venue to explore the intellec- tual migration of mathematicians and mathematics spurred by the Nazis and still influential today. The week of talks and discussions (both formal and informal) created a rich opportunity for the cross-fertilization of ideas among almost 50 mathematicians, historians of mathematics, general historians, and curators. Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 01A60. Introduction by the Organisers The talks at this conference tended to fall into the two categories of lists of sources and historical arguments built from collections of sources. This combi- nation yielded an unexpected richness as new archival materials and new angles of investigation of those archival materials came together to forge a deeper un- derstanding of the migration of mathematicians and mathematics during the Nazi era. The idea of measurement, for example, emerged as a critical idea of the confer- ence. The conference called attention to and, in fact, relied on, the seemingly stan- dard approach to measuring emigration and immigration by counting emigrants and/or immigrants and their host or departing countries. Looking further than this numerical approach, however, the conference participants learned the value of measuring emigration/immigration via other less obvious forms of measurement. 2892 Oberwolfach Report 51/2011 Forms completed by individuals on religious beliefs and other personal attributes provided an interesting cartography of Italian society in the 1930s and early 1940s. -

Implications for Understanding the Role of Affect in Mathematical Thinking

Mathematicians and music: Implications for understanding the role of affect in mathematical thinking Rena E. Gelb Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Rena E. Gelb All Rights Reserved Abstract Mathematicians and music: Implications for understanding the role of affect in mathematical thinking Rena E. Gelb The study examines the role of music in the lives and work of 20th century mathematicians within the framework of understanding the contribution of affect to mathematical thinking. The current study focuses on understanding affect and mathematical identity in the contexts of the personal, familial, communal and artistic domains, with a particular focus on musical communities. The study draws on published and archival documents and uses a multiple case study approach in analyzing six mathematicians. The study applies the constant comparative method to identify common themes across cases. The study finds that the ways the subjects are involved in music is personal, familial, communal and social, connecting them to communities of other mathematicians. The results further show that the subjects connect their involvement in music with their mathematical practices through 1) characterizing the mathematician as an artist and mathematics as an art, in particular the art of music; 2) prioritizing aesthetic criteria in their practices of mathematics; and 3) comparing themselves and other mathematicians to musicians. The results show that there is a close connection between subjects’ mathematical and musical identities. I identify eight affective elements that mathematicians display in their work in mathematics, and propose an organization of these affective elements around a view of mathematics as an art, with a particular focus on the art of music. -

Professor Richard Courant (1888 – 1972)

Professor Richard Courant (1888 – 1972) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Courant Field: Mathematics Institutions: University of Göttingen University of Münster University of Cambridge New York University Alma mater: University of Göttingen Doctoral advisor: David Hilbert Doctoral students: William Feller Martin Kruskal Joseph Keller Kurt Friedrichs Hans Lewy Franz Rellich Known for: Courant number Courant minimax principle Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy condition Biography: Courant was born in Lublinitz in the German Empire's Prussian Province of Silesia. During his youth, his parents had to move quite often, to Glatz, Breslau, and in 1905 to Berlin. He stayed in Breslau and entered the university there. As he found the courses not demanding enough, he continued his studies in Zürich and Göttingen. Courant eventually became David Hilbert's assistant in Göttingen and obtained his doctorate there in 1910. He had to fight in World War I, but he was wounded and dismissed from the military service shortly after enlisting. After the war, in 1919, he married Nerina (Nina) Runge, a daughter of the Göttingen professor for Applied Mathematics, Carl Runge. Richard continued his research in Göttingen, with a two-year period as professor in Münster. There he founded the Mathematical Institute, which he headed as director from 1928 until 1933. Courant left Germany in 1933, earlier than many of his colleagues. While he was classified as a Jew by the Nazis, his having served as a front-line soldier exempted him from losing his position for this particular reason at the time; however, his public membership in the social-democratic left was a reason for dismissal to which no such exemption applied.[1] After one year in Cambridge, Courant went to New York City where he became a professor at New York University in 1936. -

Computation of Expected Shortfall by Fast Detection of Worst Scenarios

Computation of Expected Shortfall by fast detection of worst scenarios Bruno Bouchard,∗ Adil Reghai,y Benjamin Virrionz;x May 27, 2020 Abstract We consider a multi-step algorithm for the computation of the historical expected shortfall such as defined by the Basel Minimum Capital Requirements for Market Risk. At each step of the algorithm, we use Monte Carlo simulations to reduce the number of historical scenarios that potentially belong to the set of worst scenarios. The number of simulations increases as the number of candidate scenarios is reduced and the distance between them diminishes. For the most naive scheme, we show that p the L -error of the estimator of the Expected Shortfall is bounded by a linear combination of the probabilities of inversion of favorable and unfavorable scenarios at each step, and of the last step Monte Carlo error associated to each scenario. By using concentration inequalities, we then show that, for sub-gamma pricing errors, the probabilities of inversion converge at an exponential rate in the number of simulated paths. We then propose an adaptative version in which the algorithm improves step by step its knowledge on the unknown parameters of interest: mean and variance of the Monte Carlo estimators of the different scenarios. Both schemes can be optimized by using dynamic programming algorithms that can be solved off-line. To our knowledge, these are the first non-asymptotic bounds for such estimators. Our hypotheses are weak enough to allow for the use of estimators for the different scenarios and steps based on the same random variables, which, in practice, reduces considerably the computational effort. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-61967-8 - Large-Scale Inference: Empirical Bayes Methods for Estimation, Testing, and Prediction Bradley Efron Frontmatter More information Large-Scale Inference We live in a new age for statistical inference, where modern scientific technology such as microarrays and fMRI machines routinely produce thousands and sometimes millions of parallel data sets, each with its own estimation or testing problem. Doing thousands of problems at once involves more than repeated application of classical methods. Taking an empirical Bayes approach, Bradley Efron, inventor of the bootstrap, shows how information accrues across problems in a way that combines Bayesian and frequentist ideas. Estimation, testing, and prediction blend in this framework, producing opportunities for new methodologies of increased power. New difficulties also arise, easily leading to flawed inferences. This book takes a careful look at both the promise and pitfalls of large-scale statistical inference, with particular attention to false discovery rates, the most successful of the new statistical techniques. Emphasis is on the inferential ideas underlying technical developments, illustrated using a large number of real examples. bradley efron is Max H. Stein Professor of Statistics and Biostatistics at the Stanford University School of Humanities and Sciences, and the Department of Health Research and Policy at the School of Medicine. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-61967-8 - Large-Scale Inference: Empirical Bayes Methods for Estimation, Testing, and Prediction Bradley Efron Frontmatter More information INSTITUTE OF MATHEMATICAL STATISTICS MONOGRAPHS Editorial Board D. R. Cox (University of Oxford) B. Hambly (University of Oxford) S. -

De Analysi Per Aequationes Numero Terminorum Infinitas 1669 (Published 1711) After 1696, Master of the Mint

Nick Trefethen Oxford Computing Lab Who invented the great numerical algorithms? Slides available at my web site: www.comlab.ox.ac.uk/nick.trefethen A discussion over coffee. Ivory tower or coal face? SOME MAJOR DEVELOPMENTS IN SCIENTIFIC COMPUTING (29 of them) Before 1940 Newton's method least-squares fitting orthogonal linear algebra Gaussian elimination QR algorithm Gauss quadrature Fast Fourier Transform Adams formulae quasi-Newton iterations Runge-Kutta formulae finite differences 1970-2000 preconditioning 1940-1970 spectral methods floating-point arithmetic MATLAB splines multigrid methods Monte Carlo methods IEEE arithmetic simplex algorithm nonsymmetric Krylov iterations conjugate gradients & Lanczos interior point methods Fortran fast multipole methods stiff ODE solvers wavelets finite elements automatic differentiation Before 1940 Newton’s Method for nonlinear eqs. Heron, al-Tusi 12c, Al Kashi 15c, Viète 1600, Briggs 1633… Isaac Newton 1642-1727 Mathematician and physicist Trinity College, Cambridge, 1661-1696 (BA 1665, Fellow 1667, Lucasian Professor of Mathematics 1669) De analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas 1669 (published 1711) After 1696, Master of the Mint Joseph Raphson 1648-1715 Mathematician at Jesus College, Cambridge Analysis Aequationum universalis 1690 Raphson’s formulation was better than Newton’s (“plus simple” - Lagrange 1798) FRS 1691, M.A. 1692 Supporter of Newton in the calculus wars—History of Fluxions, 1715 Thomas Simpson 1710-1761 1740: Essays on Several Curious and Useful Subjects… 1743-1761: -

Edith Stein Guild Conference Paper Draft

“Edith Stein: Family History and the Edith Stein Society of Wroclaw, Poland” New York University Catholic Center Denise De Vito Welcome to this event commemorating 125 years since the birth of Edith Stein in Breslau, Germany, on October 12, 1891, which during that year was Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement. Edith was the youngest of 11 children in the Stein family which was made up of four sons and seven daughters. However, by the time of Edith’s birth four of her siblings had already passed away. Her mother was Auguste Courant and her father was Siegfried Stein. Sometimes there is limited information on certain parents and/or family members of revered individuals such as saints, blesseds, venerables, and others in Roman Catholic church history. There are different reasons for this. The time frame of the individual’s life dates back several centuries or to the ancient world. Accurate historical data is not available. Records may have been lost, accidently destroyed, or not well preserved. Also, in some cases, there might not be sufficient interest in looking into the family background of some of these individuals. However, parents, grandparents, other family members, or close friends can influence someone’s life in diverse ways. Edith Stein’s father, Siegfried, died at the age of 49 when she was two years old. He was born in Wojska, Silesia, Poland in November, 1844. The surname Stein in German means rock or stone. His father was Simon Stein born in 1812, and his mother was Johanna Stein, formerly Cohn. Samuel J. Stein, Siegfried’s paternal grandfather, was born around 1776. -

Saul Abarbanel SIAM Oral History

An interview with SAUL ABARBANEL Conducted by Philip Davis on 29 July, 2003, at the Department of Applied Mathematics, Brown University Interview conducted by the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, as part of grant # DE-FG02-01ER25547 awarded by the US Department of Energy. Transcript and original tapes donated to the Computer History Museum by the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics © Computer History Museum Mountain View, California ABSTRACT: ABARBANEL describes his work in numerical analysis, his use of early computers, and his work with a variety of colleagues in applied mathematics. Abarbanel was born and did his early schooling in Tel Aviv, Israel, and in high school developed an interest in mathematics. After serving in the Israeli army, Abarbanel entered MIT in 1950 as an as an engineering major and took courses with Adolf Hurwitz, Francis Begnaud Hildebrand, and Philip Franklin. He found himself increasing drawn to applied mathematics, however, and by the time he began work on his Ph.D. at MIT he had switched from aeronautics to applied mathematics under the tutelage of Norman Levinson. Abarbanel recalls the frustration of dropping the punch cards for his program for the IBM 1604 that MIT was using in 1958 when he was working on his dissertation, but also notes that this work convinced him of the importance of computers. Abarbanel also relates a humorous story about Norbert Weiner, his famed linguistic aptitude, and his lesser-known interest in chess. Three years after receiving his Ph.D., Abarbanel returned to Israel, where he spent the rest of his career at Tel Aviv University.