A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics Is a Gentleman's Art: Analysis and Synthesis in American College Geometry Teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K. Ackerberg-Hastings Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Ackerberg-Hastings, Amy K., "Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 " (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 12669. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/12669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margwis, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

An Historical Review of the Theoretical Development of Rigid Body Displacements from Rodrigues Parameters to the finite Twist

Mechanism and Machine Theory Mechanism and Machine Theory 41 (2006) 41–52 www.elsevier.com/locate/mechmt An historical review of the theoretical development of rigid body displacements from Rodrigues parameters to the finite twist Jian S. Dai * Department of Mechanical Engineering, School of Physical Sciences and Engineering, King’s College London, University of London, Strand, London WC2R2LS, UK Received 5 November 2004; received in revised form 30 March 2005; accepted 28 April 2005 Available online 1 July 2005 Abstract The development of the finite twist or the finite screw displacement has attracted much attention in the field of theoretical kinematics and the proposed q-pitch with the tangent of half the rotation angle has dem- onstrated an elegant use in the study of rigid body displacements. This development can be dated back to RodriguesÕ formulae derived in 1840 with Rodrigues parameters resulting from the tangent of half the rota- tion angle being integrated with the components of the rotation axis. This paper traces the work back to the time when Rodrigues parameters were discovered and follows the theoretical development of rigid body displacements from the early 19th century to the late 20th century. The paper reviews the work from Chasles motion to CayleyÕs formula and then to HamiltonÕs quaternions and Rodrigues parameterization and relates the work to Clifford biquaternions and to StudyÕs dual angle proposed in the late 19th century. The review of the work from these mathematicians concentrates on the description and the representation of the displacement and transformation of a rigid body, and on the mathematical formulation and its progress. -

Geometric Algebras for Euclidean Geometry

Geometric algebras for euclidean geometry Charles Gunn Keywords. metric geometry, euclidean geometry, Cayley-Klein construc- tion, dual exterior algebra, projective geometry, degenerate metric, pro- jective geometric algebra, conformal geometric algebra, duality, homo- geneous model, biquaternions, dual quaternions, kinematics, rigid body motion. Abstract. The discussion of how to apply geometric algebra to euclidean n-space has been clouded by a number of conceptual misunderstandings which we first identify and resolve, based on a thorough review of cru- cial but largely forgotten themes from 19th century mathematics. We ∗ then introduce the dual projectivized Clifford algebra P(Rn;0;1) (eu- clidean PGA) as the most promising homogeneous (1-up) candidate for euclidean geometry. We compare euclidean PGA and the popular 2-up model CGA (conformal geometric algebra), restricting attention to flat geometric primitives, and show that on this domain they exhibit the same formal feature set. We thereby establish that euclidean PGA is the smallest structure-preserving euclidean GA. We compare the two algebras in more detail, with respect to a number of practical criteria, including implementation of kinematics and rigid body mechanics. We then extend the comparison to include euclidean sphere primitives. We arXiv:1411.6502v4 [math.GM] 23 May 2016 conclude that euclidean PGA provides a natural transition, both scien- tifically and pedagogically, between vector space models and the more complex and powerful CGA. 1. Introduction Although noneuclidean geometry of various sorts plays a fundamental role in theoretical physics and cosmology, the overwhelming volume of practical science and engineering takes place within classical euclidean space En. For this reason it is of no small interest to establish the best computational model for this space. -

Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the Birth of General Relativity Reviewed by David E

BOOK REVIEW Einstein’s Italian Mathematicians: Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the Birth of General Relativity Reviewed by David E. Rowe Einstein’s Italian modern Italy. Nor does the author shy away from topics Mathematicians: like how Ricci developed his absolute differential calculus Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the as a generalization of E. B. Christoffel’s (1829–1900) work Birth of General Relativity on quadratic differential forms or why it served as a key By Judith R. Goodstein tool for Einstein in his efforts to generalize the special theory of relativity in order to incorporate gravitation. In This delightful little book re- like manner, she describes how Levi-Civita was able to sulted from the author’s long- give a clear geometric interpretation of curvature effects standing enchantment with Tul- in Einstein’s theory by appealing to his concept of parallel lio Levi-Civita (1873–1941), his displacement of vectors (see below). For these and other mentor Gregorio Ricci Curbastro topics, Goodstein draws on and cites a great deal of the (1853–1925), and the special AMS, 2018, 211 pp. 211 AMS, 2018, vast secondary literature produced in recent decades by the world that these and other Ital- “Einstein industry,” in particular the ongoing project that ian mathematicians occupied and helped to shape. The has produced the first 15 volumes of The Collected Papers importance of their work for Einstein’s general theory of of Albert Einstein [CPAE 1–15, 1987–2018]. relativity is one of the more celebrated topics in the history Her account proceeds in three parts spread out over of modern mathematical physics; this is told, for example, twelve chapters, the first seven of which cover episodes in [Pais 1982], the standard biography of Einstein. -

Lecture Notes for Felix Klein Lectures

Preprint typeset in JHEP style - HYPER VERSION Lecture Notes for Felix Klein Lectures Gregory W. Moore Abstract: These are lecture notes for a series of talks at the Hausdorff Mathematical Institute, Bonn, Oct. 1-11, 2012 December 5, 2012 Contents 1. Prologue 7 2. Lecture 1, Monday Oct. 1: Introduction: (2,0) Theory and Physical Mathematics 7 2.1 Quantum Field Theory 8 2.1.1 Extended QFT, defects, and bordism categories 9 2.1.2 Traditional Wilsonian Viewpoint 12 2.2 Compactification, Low Energy Limit, and Reduction 13 2.3 Relations between theories 15 3. Background material on superconformal and super-Poincar´ealgebras 18 3.1 Why study these? 18 3.2 Poincar´eand conformal symmetry 18 3.3 Super-Poincar´ealgebras 19 3.4 Superconformal algebras 20 3.5 Six-dimensional superconformal algebras 21 3.5.1 Some group theory 21 3.5.2 The (2, 0) superconformal algebra SC(M1,5|32) 23 3.6 d = 6 (2, 0) super-Poincar´e SP(M1,5|16) and the central charge extensions 24 3.7 Compactification and preserved supersymmetries 25 3.7.1 Emergent symmetries 26 3.7.2 Partial Topological Twisting 26 3.7.3 Embedded Four-dimensional = 2 algebras and defects 28 N 3.8 Unitary Representations of the (2, 0) algebra 29 3.9 List of topological twists of the (2, 0) algebra 29 4. Four-dimensional BPS States and (primitive) Wall-Crossing 30 4.1 The d = 4, = 2 super-Poincar´ealgebra SP(M1,3|8). 30 N 4.2 BPS particle representations of four-dimensional = 2 superpoincar´eal- N gebras 31 4.2.1 Particle representations 31 4.2.2 The half-hypermultiplet 33 4.2.3 Long representations 34 -

Leonard Bernstein

chapter one Young American Bernstein at Harvard In 1982, at the age of sixty-four, Leonard Bernstein included in his col- lection of his writings, Findings, some essays from his younger days that prefi gured signifi cant elements of his later adult life and career. The fi rst, “Father’s Books,” written in 1935 when he was seventeen, is about his father and the Talmud. Throughout his life, Bernstein was ever mind- ful that he was a Jew; he composed music on Jewish themes and in later years referred to himself as a “rabbi,” a teacher with a penchant to pass on scholarly learning, wisdom, and lore to orchestral musicians.1 Moreover, Bernstein came to adopt an Old Testament prophetic voice for much of his music, including his fi rst symphony, Jeremiah, and his third, Kaddish. The second essay, “The Occult,” an assignment for a freshman composi- tion class at Harvard that he wrote in 1938 when he was twenty years old, was about meeting Dimitri Mitropoulos, who inspired him to take up conducting. The third, his senior thesis of April 1939, was a virtual man- ifesto calling for an organic, vernacular, rhythmically based, distinctly American music, a music that he later championed from the podium and realized in his compositions for the Broadway stage and operatic and concert halls.2 8 Copyrighted Material Seldes 1st pages.indd 8 9/15/2008 2:48:29 PM Young American / 9 EARLY YEARS: PROPHETIC VOICE Bernstein as an Old Testament prophet? Bernstein’s father, Sam, was born in 1892 in an ultraorthodox Jewish shtetl in Russia. -

Felix Klein and His Erlanger Programm D

WDS'07 Proceedings of Contributed Papers, Part I, 251–256, 2007. ISBN 978-80-7378-023-4 © MATFYZPRESS Felix Klein and his Erlanger Programm D. Trkovsk´a Charles University, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Prague, Czech Republic. Abstract. The present paper is dedicated to Felix Klein (1849–1925), one of the leading German mathematicians in the second half of the 19th century. It gives a brief account of his professional life. Some of his activities connected with the reform of mathematics teaching at German schools are mentioned as well. In the following text, we describe fundamental ideas of his Erlanger Programm in more detail. References containing selected papers relevant to this theme are attached. Introduction The Erlanger Programm plays an important role in the development of mathematics in the 19th century. It is the title of Klein’s famous lecture Vergleichende Betrachtungen ¨uber neuere geometrische Forschungen [A Comparative Review of Recent Researches in Geometry] which was presented on the occasion of his admission as a professor at the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Erlangen in October 1872. In this lecture, Felix Klein elucidated the importance of the term group for the classification of various geometries and presented his unified way of looking at various geometries. Klein’s basic idea is that each geometry can be characterized by a group of transformations which preserve elementary properties of the given geometry. Professional Life of Felix Klein Felix Klein was born on April 25, 1849 in D¨usseldorf,Prussia. Having finished his study at the grammar school in D¨usseldorf,he entered the University of Bonn in 1865 to study natural sciences. -

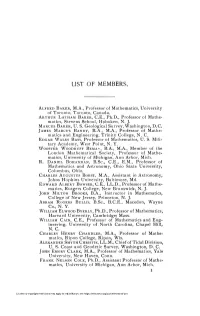

List of Members

LIST OF MEMBERS, ALFRED BAKER, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. ARTHUR LATHAM BAKER, C.E., Ph.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Stevens School, Hpboken., N. J. MARCUS BAKER, U. S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. JAMES MARCUS BANDY, B.A., M.A., Professor of Mathe matics and Engineering, Trinit)^ College, N. C. EDGAR WALES BASS, Professor of Mathematics, U. S. Mili tary Academy, West Point, N. Y. WOOSTER WOODRUFF BEMAN, B.A., M.A., Member of the London Mathematical Society, Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. R. DANIEL BOHANNAN, B.Sc, CE., E.M., Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. CHARLES AUGUSTUS BORST, M.A., Assistant in Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md. EDWARD ALBERT BOWSER, CE., LL.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Rutgers College, New Brunswick, N. J. JOHN MILTON BROOKS, B.A., Instructor in Mathematics, College of New Jersey, Princeton, N. J. ABRAM ROGERS BULLIS, B.SC, B.C.E., Macedon, Wayne Co., N. Y. WILLIAM ELWOOD BYERLY, Ph.D., Professor of Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge*, Mass. WILLIAM CAIN, C.E., Professor of Mathematics and Eng ineering, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N. C. CHARLES HENRY CHANDLER, M.A., Professor of Mathe matics, Ripon College, Ripon, Wis. ALEXANDER SMYTH CHRISTIE, LL.M., Chief of Tidal Division, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D. C. JOHN EMORY CLARK, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. FRANK NELSON COLE, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. -

The Generalization of Logic According to G.Boole, A.De Morgan

South American Journal of Logic Vol. 3, n. 2, pp. 415{481, 2017 ISSN: 2446-6719 Squaring the unknown: The generalization of logic according to G. Boole, A. De Morgan, and C. S. Peirce Cassiano Terra Rodrigues Abstract This article shows the development of symbolic mathematical logic in the works of G. Boole, A. De Morgan, and C. S. Peirce. Starting from limitations found in syllogistic, Boole devised a calculus for what he called the algebra of logic. Modifying the interpretation of categorial proposi- tions to make them agree with algebraic equations, Boole was able to show an isomorphism between the calculus of classes and of propositions, being indeed the first to mathematize logic. Having a different purport than Boole's system, De Morgan's is conceived as an improvement on syllogistic and as an instrument for the study of it. With a very unusual system of symbols of his own, De Morgan develops the study of logical relations that are defined by the very operation of signs. Although his logic is not a Boolean algebra of logic, Boole took from De Morgan at least one central notion, namely, the one of a universe of discourse. Peirce crit- ically sets out both from Boole and from De Morgan. Firstly, claiming Boole had exaggeratedly submitted logic to mathematics, Peirce strives to distinguish the nature and the purpose of each discipline. Secondly, identifying De Morgan's limitations in his rigid restraint of logic to the study of relations, Peirce develops compositions of relations with classes. From such criticisms, Peirce not only devises a multiple quantification theory, but also construes a very original and strong conception of logic as a normative science. -

Mathematical Genealogy of the Wellesley College Department Of

Nilos Kabasilas Mathematical Genealogy of the Wellesley College Department of Mathematics Elissaeus Judaeus Demetrios Kydones The Mathematics Genealogy Project is a service of North Dakota State University and the American Mathematical Society. http://www.genealogy.math.ndsu.nodak.edu/ Georgios Plethon Gemistos Manuel Chrysoloras 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Johannes Argyropoulos Guarino da Verona 1444 Università di Padova 1408 Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino Vittorino da Feltre 1462 Università di Firenze 1416 Università di Padova Angelo Poliziano Theodoros Gazes Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo 1477 Università di Firenze 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova Università di Mantova Leo Outers Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Thomas à Kempis Rudolf Agricola Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro François Dubois Jean Tagault Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Pelope Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe -

Peirce for Whitehead Handbook

For M. Weber (ed.): Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought Ontos Verlag, Frankfurt, 2008, vol. 2, 481-487 Charles S. Peirce (1839-1914) By Jaime Nubiola1 1. Brief Vita Charles Sanders Peirce [pronounced "purse"], was born on 10 September 1839 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to Sarah and Benjamin Peirce. His family was already academically distinguished, his father being a professor of astronomy and mathematics at Harvard. Though Charles himself received a graduate degree in chemistry from Harvard University, he never succeeded in obtaining a tenured academic position. Peirce's academic ambitions were frustrated in part by his difficult —perhaps manic-depressive— personality, combined with the scandal surrounding his second marriage, which he contracted soon after his divorce from Harriet Melusina Fay. He undertook a career as a scientist for the United States Coast Survey (1859- 1891), working especially in geodesy and in pendulum determinations. From 1879 through 1884, he was a part-time lecturer in Logic at Johns Hopkins University. In 1887, Peirce moved with his second wife, Juliette Froissy, to Milford, Pennsylvania, where in 1914, after 26 years of prolific and intense writing, he died of cancer. He had no children. Peirce published two books, Photometric Researches (1878) and Studies in Logic (1883), and a large number of papers in journals in widely differing areas. His manuscripts, a great many of which remain unpublished, run to some 100,000 pages. In 1931-58, a selection of his writings was arranged thematically and published in eight volumes as the Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Beginning in 1982, a number of volumes have been published in the series A Chronological Edition, which will ultimately consist of thirty volumes. -

A History of Mathematics in America Before 1900.Pdf

THE BOOK WAS DRENCHED 00 S< OU_1 60514 > CD CO THE CARUS MATHEMATICAL MONOGRAPHS Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Publication Committee GILBERT AMES BLISS DAVID RAYMOND CURTISS AUBREY JOHN KEMPNER HERBERT ELLSWORTH SLAUGHT CARUS MATHEMATICAL MONOGRAPHS are an expression of THEthe desire of Mrs. Mary Hegeler Carus, and of her son, Dr. Edward H. Carus, to contribute to the dissemination of mathe- matical knowledge by making accessible at nominal cost a series of expository presenta- tions of the best thoughts and keenest re- searches in pure and applied mathematics. The publication of these monographs was made possible by a notable gift to the Mathematical Association of America by Mrs. Carus as sole trustee of the Edward C. Hegeler Trust Fund. The expositions of mathematical subjects which the monographs will contain are to be set forth in a manner comprehensible not only to teach- ers and students specializing in mathematics, but also to scientific workers in other fields, and especially to the wide circle of thoughtful people who, having a moderate acquaintance with elementary mathematics, wish to extend their knowledge without prolonged and critical study of the mathematical journals and trea- tises. The scope of this series includes also historical and biographical monographs. The Carus Mathematical Monographs NUMBER FIVE A HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS IN AMERICA BEFORE 1900 By DAVID EUGENE SMITH Professor Emeritus of Mathematics Teacliers College, Columbia University and JEKUTHIEL GINSBURG Professor of Mathematics in Yeshiva College New York and Editor of "Scripta Mathematica" Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA with the cooperation of THE OPEN COURT PUBLISHING COMPANY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS THE OPEN COURT COMPANY Copyright 1934 by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMKRICA Published March, 1934 Composed, Printed and Bound by tClfe QlolUgUt* $Jrr George Banta Publishing Company Menasha, Wisconsin, U.