Cathleen Synge Morawetz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

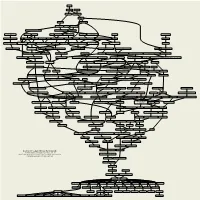

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction To

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Springer-V erlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH Richard Courant • Fritz John Introd uction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Reprint of the 1989 Edition Springer Originally published in 1965 by Interscience Publishers, a division of John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Reprinted in 1989 by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. Mathematics Subject Classification (1991): 26-XX, 26-01 Cataloging in Publication Data applied for Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Courant, Richard: Introduction to calcu1us and analysis / Richard Courant; Fritz John.- Reprint of the 1989 ed.- Berlin; Heidelberg; New York; Barcelona; Hong Kong; London; Milan; Paris; Singapore; Tokyo: Springer (Classics in mathematics) VoL 1 (1999) ISBN 978-3-540-65058-4 ISBN 978-3-642-58604-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-58604-0 Photograph of Richard Courant from: C. Reid, Courant in Gottingen and New York. The Story of an Improbable Mathematician, Springer New York, 1976 Photograph of Fritz John by kind permission of The Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York ISSN 1431-0821 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved. whether the whole or part of the material is concemed. specifically the rights of trans1ation. reprinting. reuse of illustrations. recitation. broadcasting. reproduction on microfilm or in any other way. and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted onlyunder the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9.1965. in its current version. and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are Iiable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. -

President's Report

AWM ASSOCIATION FOR WOMEN IN MATHE MATICS Volume 36, Number l NEWSLETTER March-April 2006 President's Report Hidden Help TheAWM election results are in, and it is a pleasure to welcome Cathy Kessel, who became President-Elect on February 1, and Dawn Lott, Alice Silverberg, Abigail Thompson, and Betsy Yanik, the new Members-at-Large of the Executive Committee. Also elected for a second term as Clerk is Maura Mast.AWM is also pleased to announce that appointed members BettyeAnne Case (Meetings Coordi nator), Holly Gaff (Web Editor) andAnne Leggett (Newsletter Editor) have agreed to be re-appointed, while Fern Hunt and Helen Moore have accepted an extension of their terms as Member-at-Large, to join continuing members Krystyna Kuperberg andAnn Tr enk in completing the enlarged Executive Committee. I look IN THIS ISSUE forward to working with this wonderful group of people during the coming year. 5 AWM ar the San Antonio In SanAntonio in January 2006, theAssociation for Women in Mathematics Joint Mathematics Meetings was, as usual, very much in evidence at the Joint Mathematics Meetings: from 22 Girls Just Want to Have Sums the outstanding mathematical presentations by women senior and junior, in the Noerher Lecture and the Workshop; through the Special Session on Learning Theory 24 Education Column thatAWM co-sponsored withAMS and MAA in conjunction with the Noether Lecture; to the two panel discussions thatAWM sponsored/co-sponsored.AWM 26 Book Review also ran two social events that were open to the whole community: a reception following the Gibbs lecture, with refreshments and music that was just right for 28 In Memoriam a networking event, and a lunch for Noether lecturer Ingrid Daubechies. -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Emigration Of

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 51/2011 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2011/51 Emigration of Mathematicians and Transmission of Mathematics: Historical Lessons and Consequences of the Third Reich Organised by June Barrow-Green, Milton-Keynes Della Fenster, Richmond Joachim Schwermer, Wien Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze, Kristiansand October 30th – November 5th, 2011 Abstract. This conference provided a focused venue to explore the intellec- tual migration of mathematicians and mathematics spurred by the Nazis and still influential today. The week of talks and discussions (both formal and informal) created a rich opportunity for the cross-fertilization of ideas among almost 50 mathematicians, historians of mathematics, general historians, and curators. Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 01A60. Introduction by the Organisers The talks at this conference tended to fall into the two categories of lists of sources and historical arguments built from collections of sources. This combi- nation yielded an unexpected richness as new archival materials and new angles of investigation of those archival materials came together to forge a deeper un- derstanding of the migration of mathematicians and mathematics during the Nazi era. The idea of measurement, for example, emerged as a critical idea of the confer- ence. The conference called attention to and, in fact, relied on, the seemingly stan- dard approach to measuring emigration and immigration by counting emigrants and/or immigrants and their host or departing countries. Looking further than this numerical approach, however, the conference participants learned the value of measuring emigration/immigration via other less obvious forms of measurement. 2892 Oberwolfach Report 51/2011 Forms completed by individuals on religious beliefs and other personal attributes provided an interesting cartography of Italian society in the 1930s and early 1940s. -

Implications for Understanding the Role of Affect in Mathematical Thinking

Mathematicians and music: Implications for understanding the role of affect in mathematical thinking Rena E. Gelb Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Rena E. Gelb All Rights Reserved Abstract Mathematicians and music: Implications for understanding the role of affect in mathematical thinking Rena E. Gelb The study examines the role of music in the lives and work of 20th century mathematicians within the framework of understanding the contribution of affect to mathematical thinking. The current study focuses on understanding affect and mathematical identity in the contexts of the personal, familial, communal and artistic domains, with a particular focus on musical communities. The study draws on published and archival documents and uses a multiple case study approach in analyzing six mathematicians. The study applies the constant comparative method to identify common themes across cases. The study finds that the ways the subjects are involved in music is personal, familial, communal and social, connecting them to communities of other mathematicians. The results further show that the subjects connect their involvement in music with their mathematical practices through 1) characterizing the mathematician as an artist and mathematics as an art, in particular the art of music; 2) prioritizing aesthetic criteria in their practices of mathematics; and 3) comparing themselves and other mathematicians to musicians. The results show that there is a close connection between subjects’ mathematical and musical identities. I identify eight affective elements that mathematicians display in their work in mathematics, and propose an organization of these affective elements around a view of mathematics as an art, with a particular focus on the art of music. -

RM Calendar 2017

Rudi Mathematici x3 – 6’135x2 + 12’545’291 x – 8’550’637’845 = 0 www.rudimathematici.com 1 S (1803) Guglielmo Libri Carucci dalla Sommaja RM132 (1878) Agner Krarup Erlang Rudi Mathematici (1894) Satyendranath Bose RM168 (1912) Boris Gnedenko 1 2 M (1822) Rudolf Julius Emmanuel Clausius (1905) Lev Genrichovich Shnirelman (1938) Anatoly Samoilenko 3 T (1917) Yuri Alexeievich Mitropolsky January 4 W (1643) Isaac Newton RM071 5 T (1723) Nicole-Reine Etable de Labrière Lepaute (1838) Marie Ennemond Camille Jordan Putnam 2002, A1 (1871) Federigo Enriques RM084 Let k be a fixed positive integer. The n-th derivative of (1871) Gino Fano k k n+1 1/( x −1) has the form P n(x)/(x −1) where P n(x) is a 6 F (1807) Jozeph Mitza Petzval polynomial. Find P n(1). (1841) Rudolf Sturm 7 S (1871) Felix Edouard Justin Emile Borel A college football coach walked into the locker room (1907) Raymond Edward Alan Christopher Paley before a big game, looked at his star quarterback, and 8 S (1888) Richard Courant RM156 said, “You’re academically ineligible because you failed (1924) Paul Moritz Cohn your math mid-term. But we really need you today. I (1942) Stephen William Hawking talked to your math professor, and he said that if you 2 9 M (1864) Vladimir Adreievich Steklov can answer just one question correctly, then you can (1915) Mollie Orshansky play today. So, pay attention. I really need you to 10 T (1875) Issai Schur concentrate on the question I’m about to ask you.” (1905) Ruth Moufang “Okay, coach,” the player agreed. -

Professor Richard Courant (1888 – 1972)

Professor Richard Courant (1888 – 1972) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Courant Field: Mathematics Institutions: University of Göttingen University of Münster University of Cambridge New York University Alma mater: University of Göttingen Doctoral advisor: David Hilbert Doctoral students: William Feller Martin Kruskal Joseph Keller Kurt Friedrichs Hans Lewy Franz Rellich Known for: Courant number Courant minimax principle Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy condition Biography: Courant was born in Lublinitz in the German Empire's Prussian Province of Silesia. During his youth, his parents had to move quite often, to Glatz, Breslau, and in 1905 to Berlin. He stayed in Breslau and entered the university there. As he found the courses not demanding enough, he continued his studies in Zürich and Göttingen. Courant eventually became David Hilbert's assistant in Göttingen and obtained his doctorate there in 1910. He had to fight in World War I, but he was wounded and dismissed from the military service shortly after enlisting. After the war, in 1919, he married Nerina (Nina) Runge, a daughter of the Göttingen professor for Applied Mathematics, Carl Runge. Richard continued his research in Göttingen, with a two-year period as professor in Münster. There he founded the Mathematical Institute, which he headed as director from 1928 until 1933. Courant left Germany in 1933, earlier than many of his colleagues. While he was classified as a Jew by the Nazis, his having served as a front-line soldier exempted him from losing his position for this particular reason at the time; however, his public membership in the social-democratic left was a reason for dismissal to which no such exemption applied.[1] After one year in Cambridge, Courant went to New York City where he became a professor at New York University in 1936. -

Homogenization 2001, Proceedings of the First HMS2000 International School and Conference on Ho- Mogenization

in \Homogenization 2001, Proceedings of the First HMS2000 International School and Conference on Ho- mogenization. Naples, Complesso Monte S. Angelo, June 18-22 and 23-27, 2001, Ed. L. Carbone and R. De Arcangelis, 191{211, Gakkotosho, Tokyo, 2003". On Homogenization and Γ-convergence Luc TARTAR1 In memory of Ennio DE GIORGI When in the Fall of 1976 I had chosen \Homog´en´eisationdans les ´equationsaux d´eriv´eespartielles" (Homogenization in partial differential equations) for the title of my Peccot lectures, which I gave in the beginning of 1977 at Coll`egede France in Paris, I did not know of the term Γ-convergence, which I first heard almost a year after, in a talk that Ennio DE GIORGI gave in the seminar that Jacques-Louis LIONS was organizing at Coll`egede France on Friday afternoons. I had not found the definition of Γ-convergence really new, as it was quite similar to questions that were already discussed in control theory under the name of relaxation (which was a more general question than what most people mean by that term now), and it was the convergence in the sense of Umberto MOSCO [Mos] but without the restriction to convex functionals, and it was the natural nonlinear analog of a result concerning G-convergence that Ennio DE GIORGI had obtained with Sergio SPAGNOLO [DG&Spa]; however, Ennio DE GIORGI's talk contained a quite interesting example, for which he referred to Luciano MODICA (and Stefano MORTOLA) [Mod&Mor], where functionals involving surface integrals appeared as Γ-limits of functionals involving volume integrals, and I thought that it was the interesting part of the concept, so I had found it similar to previous questions but I had felt that the point of view was slightly different. -

De Analysi Per Aequationes Numero Terminorum Infinitas 1669 (Published 1711) After 1696, Master of the Mint

Nick Trefethen Oxford Computing Lab Who invented the great numerical algorithms? Slides available at my web site: www.comlab.ox.ac.uk/nick.trefethen A discussion over coffee. Ivory tower or coal face? SOME MAJOR DEVELOPMENTS IN SCIENTIFIC COMPUTING (29 of them) Before 1940 Newton's method least-squares fitting orthogonal linear algebra Gaussian elimination QR algorithm Gauss quadrature Fast Fourier Transform Adams formulae quasi-Newton iterations Runge-Kutta formulae finite differences 1970-2000 preconditioning 1940-1970 spectral methods floating-point arithmetic MATLAB splines multigrid methods Monte Carlo methods IEEE arithmetic simplex algorithm nonsymmetric Krylov iterations conjugate gradients & Lanczos interior point methods Fortran fast multipole methods stiff ODE solvers wavelets finite elements automatic differentiation Before 1940 Newton’s Method for nonlinear eqs. Heron, al-Tusi 12c, Al Kashi 15c, Viète 1600, Briggs 1633… Isaac Newton 1642-1727 Mathematician and physicist Trinity College, Cambridge, 1661-1696 (BA 1665, Fellow 1667, Lucasian Professor of Mathematics 1669) De analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas 1669 (published 1711) After 1696, Master of the Mint Joseph Raphson 1648-1715 Mathematician at Jesus College, Cambridge Analysis Aequationum universalis 1690 Raphson’s formulation was better than Newton’s (“plus simple” - Lagrange 1798) FRS 1691, M.A. 1692 Supporter of Newton in the calculus wars—History of Fluxions, 1715 Thomas Simpson 1710-1761 1740: Essays on Several Curious and Useful Subjects… 1743-1761: -

Deborah and Franklin Tepper Haimo Awards for Distinguished College Or University Teaching of Mathematics

MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA DEBORAH AND FRANKLIN TEPPER HAIMO AWARDS FOR DISTINGUISHED COLLEGE OR UNIVERSITY TEACHING OF MATHEMATICS In 1991, the Mathematical Association of America instituted the Deborah and Franklin Tepper Haimo Awards for Distinguished College or University Teaching of Mathematics in order to honor college or university teachers who have been widely recognized as extraordinarily successful and whose teaching effectiveness has been shown to have had influence beyond their own institutions. Deborah Tepper Haimo was President of the Association, 1991–1992. Citation Jacqueline Dewar In her 32 years at Loyola Marymount University, Jackie Dewar’s enthusiasm, extraordinary energy, and clarity of thought have left a deep imprint on students, colleagues, her campus, and a much larger mathematical community. A student testifies, “Dr. Dewar has engaged the curious nature and imaginations of students from all disciplines by continuously providing them with problems (and props!), whose solutions require steady devotion and creativity….” A colleague who worked closely with her on the Los Angeles Collaborative for Teacher Excellence (LACTE) describes her many “watch and learn” experiences with Jackie, and says, “I continue to hear Jackie’s words, ‘Is this your best work?’—both in the classroom and in all professional endeavors. ...[she] will always listen to my ideas, ask insightful and pertinent questions, and offer constructive and honest advice to improve my work.” As a 2003–2004 CASTL (Carnegie Academy for the Scholarship -

Mathematics to the Rescue Retiring Presidential Address

morawetz.qxp 11/13/98 11:20 AM Page 9 Mathematics to the Rescue (Retiring Presidential Address) Cathleen Synge Morawetz should like to dedicate this lecture to my tial equation by a simple difference scheme and get- teacher, Kurt Otto Friedrichs. While many ting nonsense because the scheme is unstable. people helped me on my way professionally, The answers blow up. The white knights—Courant, Friedrichs played the central role, first as my Friedrichs, and Lewy (CFL)—would then step in thesis advisor and then by feeding me early and show them that mathematics could cure the Iresearch problems. He was my friend and col- problem. That was, however, not the way. But first, league for almost forty years. As is true among what is the CFL condition? It says [1] that for sta- friends, he was sometimes exasperated with me (I ble schemes the step size in time is limited by the was too disorderly), and sometimes he exasperated step size in space. The simplest example is the dif- me (he was just too orderly). However, I think we ference scheme for a solution of the wave equa- appreciated each other’s virtues, and I learned a tion great deal from him. utt uxx =0 Sometimes we had quite different points of − view. In his old age he agreed to be interviewed, on a grid that looks like the one in Figure 1. Sec- at Jack Schwartz’s request, for archival purposes. ond derivatives are replaced by second-order I was the interviewer. At one point I asked him differences with t = x. -

Edith Stein Guild Conference Paper Draft

“Edith Stein: Family History and the Edith Stein Society of Wroclaw, Poland” New York University Catholic Center Denise De Vito Welcome to this event commemorating 125 years since the birth of Edith Stein in Breslau, Germany, on October 12, 1891, which during that year was Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement. Edith was the youngest of 11 children in the Stein family which was made up of four sons and seven daughters. However, by the time of Edith’s birth four of her siblings had already passed away. Her mother was Auguste Courant and her father was Siegfried Stein. Sometimes there is limited information on certain parents and/or family members of revered individuals such as saints, blesseds, venerables, and others in Roman Catholic church history. There are different reasons for this. The time frame of the individual’s life dates back several centuries or to the ancient world. Accurate historical data is not available. Records may have been lost, accidently destroyed, or not well preserved. Also, in some cases, there might not be sufficient interest in looking into the family background of some of these individuals. However, parents, grandparents, other family members, or close friends can influence someone’s life in diverse ways. Edith Stein’s father, Siegfried, died at the age of 49 when she was two years old. He was born in Wojska, Silesia, Poland in November, 1844. The surname Stein in German means rock or stone. His father was Simon Stein born in 1812, and his mother was Johanna Stein, formerly Cohn. Samuel J. Stein, Siegfried’s paternal grandfather, was born around 1776.