Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Emigration Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

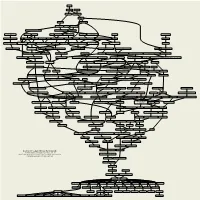

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

Life and Work of Egbert Brieskorn (1936 – 2013)1

Special volume in honor of the life Journal of Singularities and mathematics of Egbert Brieskorn Volume 18 (2018), 1-28 DOI: 10.5427/jsing.2018.18a LIFE AND WORK OF EGBERT BRIESKORN (1936 – 2013)1 GERT-MARTIN GREUEL AND WALTER PURKERT Brieskorn 2007 Egbert Brieskorn died on July 11, 2013, a few days after his 77th birthday. He was an im- pressive personality who left a lasting impression on anyone who knew him, be it in or out of mathematics. Brieskorn was a great mathematician, but his interests, knowledge, and activities went far beyond mathematics. In the following article, which is strongly influenced by the au- thors’ many years of personal ties with Brieskorn, we try to give a deeper insight into the life and work of Brieskorn. In doing so, we highlight both his personal commitment to peace and the environment as well as his long–standing exploration of the life and work of Felix Hausdorff and the publication of Hausdorff ’s Collected Works. The focus of the article, however, is on the presentation of his remarkable and influential mathematical work. The first author (GMG) has spent significant parts of his scientific career as a graduate and doctoral student with Brieskorn in Göttingen and later as his assistant in Bonn. He describes in the first two parts, partly from the memory of personal cooperation, aspects of Brieskorn’s life and of his political and social commitment. In addition, in the section on Brieskorn’s mathematical work, he explains in detail the main scientific results of his publications. The second author (WP) worked together with Brieskorn for many years, mainly in connection with the Hausdorff project; the corresponding section on the Hausdorff project was written by him. -

Academic Profiles of Conference Speakers

Academic Profiles of Conference Speakers 1. Cavazza, Marta, Associate Professor of the History of Science in the Facoltà di Scienze della Formazione (University of Bologna) Professor Cavazza’s research interests encompass seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Italian scientific institutions, in particular those based in Bologna, with special attention to their relations with the main European cultural centers of the age, namely the Royal Society of London and the Academy of Sciences in Paris. She also focuses on the presence of women in eighteenth- century Italian scientific institutions and the Enlightenment debate on gender, culture and society. Most of Cavazza’s published works on these topics center on Laura Bassi (1711-1778), the first woman university professor at Bologna, thanks in large part to the patronage of Benedict XIV. She is currently involved in the organization of the rich program of events for the celebration of the third centenary of Bassi’s birth. Select publications include: Settecento inquieto: Alle origini dell’Istituto delle Scienze (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1990); “The Institute of science of Bologna and The Royal Society in the Eighteenth century”, Notes and Records of The Royal Society, 56 (2002), 1, pp. 3- 25; “Una donna nella repubblica degli scienziati: Laura Bassi e i suoi colleghi,” in Scienza a due voci, (Firenze: Leo Olschki, 2006); “From Tournefort to Linnaeus: The Slow Conversion of the Institute of Sciences of Bologna,” in Linnaeus in Italy: The Spread of a Revolution in Science, (Science History Publications/USA, 2007); “Innovazione e compromesso. L'Istituto delle Scienze e il sistema accademico bolognese del Settecento,” in Bologna nell'età moderna, tomo II. -

Meetings & Conferences of The

Meetings & Conferences of the AMS IMPORTANT INFORMATION REGARDING MEETINGS PROGRAMS: AMS Sectional Meeting programs do not appear in the print version of the Notices. However, comprehensive and continually updated meeting and program information with links to the abstract for each talk can be found on the AMS website. See http://www.ams.org/ meetings/. Final programs for Sectional Meetings will be archived on the AMS website accessible from the stated URL and in an electronic issue of the Notices as noted below for each meeting. Tamar Zeigler, Technion, Israel Institute of Technology, Tel Aviv, Israel Patterns in primes and dynamics on nilmanifolds. Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan and Special Sessions Tel-Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv Additive Number Theory, Melvyn B. Nathanson, City University of New York, and Yonutz V. Stanchescu, Afeka June 16–19, 2014 Tel Aviv Academic College of Engineering. Monday – Thursday Algebraic Groups, Division Algebras and Galois Co- homology, Andrei Rapinchuk, University of Virginia, and Meeting #1101 Louis H. Rowen and Uzi Vishne, Bar Ilan University. The Second Joint International Meeting between the AMS Applications of Algebra to Cryptography, David Garber, and the Israel Mathematical Union. Holon Institute of Technology, and Delaram Kahrobaei, Associate secretary: Michel L. Lapidus City University of New York Graduate Center. Announcement issue of Notices: January 2014 Asymptotic Geometric Analysis, Shiri Artstein and Boaz Program first available on AMS website: To be announced Klar’tag, Tel Aviv University, and Sasha Sodin, Princeton Program issue of electronic Notices: To be announced University. Issue of Abstracts: Not applicable Combinatorial Games, Aviezri Fraenkel, Weizmann University, Richard Nowakowski, Dalhousie University, Deadlines Canada, Thane Plambeck, Counterwave Inc., and Aaron For organizers: To be announced Siegel, Twitter. -

License Or Copyright Restrictions May Apply to Redistribution; See Https

License or copyright restrictions may apply to redistribution; see https://www.ams.org/journal-terms-of-use License or copyright restrictions may apply to redistribution; see https://www.ams.org/journal-terms-of-use EMIL ARTIN BY RICHARD BRAUER Emil Artin died of a heart attack on December 20, 1962 at the age of 64. His unexpected death came as a tremendous shock to all who knew him. There had not been any danger signals. It was hard to realize that a person of such strong vitality was gone, that such a great mind had been extinguished by a physical failure of the body. Artin was born in Vienna on March 3,1898. He grew up in Reichen- berg, now Tschechoslovakia, then still part of the Austrian empire. His childhood seems to have been lonely. Among the happiest periods was a school year which he spent in France. What he liked best to remember was his enveloping interest in chemistry during his high school days. In his own view, his inclination towards mathematics did not show before his sixteenth year, while earlier no trace of mathe matical aptitude had been apparent.1 I have often wondered what kind of experience it must have been for a high school teacher to have a student such as Artin in his class. During the first world war, he was drafted into the Austrian Army. After the war, he studied at the University of Leipzig from which he received his Ph.D. in 1921. He became "Privatdozent" at the Univer sity of Hamburg in 1923. -

Emil Artin in America

MATHEMATICAL PERSPECTIVES BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 50, Number 2, April 2013, Pages 321–330 S 0273-0979(2012)01398-8 Article electronically published on December 18, 2012 CREATING A LIFE: EMIL ARTIN IN AMERICA DELLA DUMBAUGH AND JOACHIM SCHWERMER 1. Introduction In January 1933, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party assumed control of Germany. On 7 April of that year the Nazis created the notion of “non-Aryan descent”.1 “It was only a question of time”, Richard Brauer would later describe it, “until [Emil] Artin, with his feeling for individual freedom, his sense of justice, his abhorrence of physical violence would leave Germany” [5, p. 28]. By the time Hitler issued the edict on 26 January 1937, which removed any employee married to a Jew from their position as of 1 July 1937,2 Artin had already begun to make plans to leave Germany. Artin had married his former student, Natalie Jasny, in 1929, and, since she had at least one Jewish grandparent, the Nazis classified her as Jewish. On 1 October 1937, Artin and his family arrived in America [19, p. 80]. The surprising combination of a Roman Catholic university and a celebrated American mathematician known for his gnarly personality played a critical role in Artin’s emigration to America. Solomon Lefschetz had just served as AMS president from 1935–1936 when Artin came to his attention: “A few days ago I returned from a meeting of the American Mathematical Society where as President, I was particularly well placed to know what was going on”, Lefschetz wrote to the president of Notre Dame on 12 January 1937, exactly two weeks prior to the announcement of the Hitler edict that would influence Artin directly. -

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction To

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Springer-V erlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH Richard Courant • Fritz John Introd uction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Reprint of the 1989 Edition Springer Originally published in 1965 by Interscience Publishers, a division of John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Reprinted in 1989 by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. Mathematics Subject Classification (1991): 26-XX, 26-01 Cataloging in Publication Data applied for Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Courant, Richard: Introduction to calcu1us and analysis / Richard Courant; Fritz John.- Reprint of the 1989 ed.- Berlin; Heidelberg; New York; Barcelona; Hong Kong; London; Milan; Paris; Singapore; Tokyo: Springer (Classics in mathematics) VoL 1 (1999) ISBN 978-3-540-65058-4 ISBN 978-3-642-58604-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-58604-0 Photograph of Richard Courant from: C. Reid, Courant in Gottingen and New York. The Story of an Improbable Mathematician, Springer New York, 1976 Photograph of Fritz John by kind permission of The Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York ISSN 1431-0821 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved. whether the whole or part of the material is concemed. specifically the rights of trans1ation. reprinting. reuse of illustrations. recitation. broadcasting. reproduction on microfilm or in any other way. and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted onlyunder the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9.1965. in its current version. and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are Iiable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. -

LECTURE Series

University LECTURE Series Volume 52 Koszul Cohomology and Algebraic Geometry Marian Aprodu Jan Nagel American Mathematical Society http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/ulect/052 Koszul Cohomology and Algebraic Geometry University LECTURE Series Volume 52 Koszul Cohomology and Algebraic Geometry Marian Aprodu Jan Nagel M THE ATI A CA M L ΤΡΗΤΟΣ ΜΗ N ΕΙΣΙΤΩ S A O C C I I R E E T ΑΓΕΩΜΕ Y M A F O 8 U 88 NDED 1 American Mathematical Society Providence, Rhode Island EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Jerry L. Bona NigelD.Higson Eric M. Friedlander (Chair) J. T. Stafford 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 14H51, 14C20, 14H60, 14J28, 13D02, 16E05. For additional information and updates on this book, visit www.ams.org/bookpages/ulect-52 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aprodu, Marian. Koszul cohomology and algebraic geometry / Marian Aprodu, Jan Nagel. p. cm. — (University lecture series ; v. 52) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8218-4964-4 (alk. paper) 1. Koszul algebras. 2. Geometry, Algebraic. 3. Homology theory. I. Nagel, Jan. II. Title. QA564.A63 2010 512.46—dc22 2009042378 Copying and reprinting. Individual readers of this publication, and nonprofit libraries acting for them, are permitted to make fair use of the material, such as to copy a chapter for use in teaching or research. Permission is granted to quote brief passages from this publication in reviews, provided the customary acknowledgment of the source is given. Republication, systematic copying, or multiple reproduction of any material in this publication is permitted only under license from the American Mathematical Society. -

Herbert Busemann (1905--1994)

HERBERT BUSEMANN (1905–1994) A BIOGRAPHY FOR HIS SELECTED WORKS EDITION ATHANASE PAPADOPOULOS Herbert Busemann1 was born in Berlin on May 12, 1905 and he died in Santa Ynez, County of Santa Barbara (California) on February 3, 1994, where he used to live. His first paper was published in 1930, and his last one in 1993. He wrote six books, two of which were translated into Russian in the 1960s. Initially, Busemann was not destined for a mathematical career. His father was a very successful businessman who wanted his son to be- come, like him, a businessman. Thus, the young Herbert, after high school (in Frankfurt and Essen), spent two and a half years in business. Several years later, Busemann recalls that he always wanted to study mathematics and describes this period as “two and a half lost years of my life.” Busemann started university in 1925, at the age of 20. Between the years 1925 and 1930, he studied in Munich (one semester in the aca- demic year 1925/26), Paris (the academic year 1927/28) and G¨ottingen (one semester in 1925/26, and the years 1928/1930). He also made two 1Most of the information about Busemann is extracted from the following sources: (1) An interview with Constance Reid, presumably made on April 22, 1973 and kept at the library of the G¨ottingen University. (2) Other documents held at the G¨ottingen University Library, published in Vol- ume II of the present edition of Busemann’s Selected Works. (3) Busemann’s correspondence with Richard Courant which is kept at the Archives of New York University. -

Simply-Riemann-1588263529. Print

Simply Riemann Simply Riemann JEREMY GRAY SIMPLY CHARLY NEW YORK Copyright © 2020 by Jeremy Gray Cover Illustration by José Ramos Cover Design by Scarlett Rugers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-943657-21-6 Brought to you by http://simplycharly.com Contents Praise for Simply Riemann vii Other Great Lives x Series Editor's Foreword xi Preface xii Introduction 1 1. Riemann's life and times 7 2. Geometry 41 3. Complex functions 64 4. Primes and the zeta function 87 5. Minimal surfaces 97 6. Real functions 108 7. And another thing . 124 8. Riemann's Legacy 126 References 143 Suggested Reading 150 About the Author 152 A Word from the Publisher 153 Praise for Simply Riemann “Jeremy Gray is one of the world’s leading historians of mathematics, and an accomplished author of popular science. In Simply Riemann he combines both talents to give us clear and accessible insights into the astonishing discoveries of Bernhard Riemann—a brilliant but enigmatic mathematician who laid the foundations for several major areas of today’s mathematics, and for Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity.Readable, organized—and simple. Highly recommended.” —Ian Stewart, Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at Warwick University and author of Significant Figures “Very few mathematicians have exercised an influence on the later development of their science comparable to Riemann’s whose work reshaped whole fields and created new ones. -

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Individual Fates and Global Impact Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze princeton university press princeton and oxford Copyright 2009 © by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siegmund-Schultze, R. (Reinhard) Mathematicians fleeing from Nazi Germany: individual fates and global impact / Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-12593-0 (cloth) — ISBN 978-0-691-14041-4 (pbk.) 1. Mathematicians—Germany—History—20th century. 2. Mathematicians— United States—History—20th century. 3. Mathematicians—Germany—Biography. 4. Mathematicians—United States—Biography. 5. World War, 1939–1945— Refuges—Germany. 6. Germany—Emigration and immigration—History—1933–1945. 7. Germans—United States—History—20th century. 8. Immigrants—United States—History—20th century. 9. Mathematics—Germany—History—20th century. 10. Mathematics—United States—History—20th century. I. Title. QA27.G4S53 2008 510.09'04—dc22 2008048855 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 Contents List of Figures and Tables xiii Preface xvii Chapter 1 The Terms “German-Speaking Mathematician,” “Forced,” and“Voluntary Emigration” 1 Chapter 2 The Notion of “Mathematician” Plus Quantitative Figures on Persecution 13 Chapter 3 Early Emigration 30 3.1. The Push-Factor 32 3.2. The Pull-Factor 36 3.D. -

Vector Spaces

19 Vector Spaces Still round the corner there may wait A new road or a secret gate. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring The art of doing mathematics consists in finding that special case which contains all the germs of generality. David Hilbert (1862–1943) Definition and Examples Abstract algebra has three basic components: groups, rings, and fields. Thus far we have covered groups and rings in some detail, and we have touched on the notion of a field. To explore fields more deeply, we need some rudiments of vector space theory that are covered in a linear alge- bra course. In this chapter, we provide a concise review of this material. Definition Vector Space A set V is said to be a vector space over a field F if V is an Abelian group under addition (denoted by 1) and, if for each a [ F and v [ V, there is an element av in V such that the following conditions hold for all a, b in F and all u, v in V. 1. a(v 1 u) 5 av 1 au 2. (a 1 b)v 5 av 1 bv 3. a(bv) 5 (ab)v 4. 1v 5 v The members of a vector space are called vectors. The members of the field are called scalars. The operation that combines a scalar a and a vector v to form the vector av is called scalar multiplication. In gen- eral, we will denote vectors by letters from the end of the alphabet, such as u, v, w, and scalars by letters from the beginning of the alpha- bet, such as a, b, c.