Emmy Noether and Bryn Mawr College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

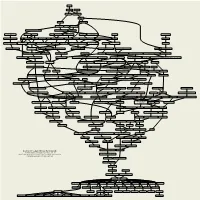

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

Of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7 The Mathematics of Gravitational Waves: A Two-Part Feature page 684 The Travel Ban: Affected Mathematicians Tell Their Stories page 678 The Global Math Project: Uplifting Mathematics for All page 712 2015–2016 Doctoral Degrees Conferred page 727 Gravitational waves are produced by black holes spiraling inward (see page 674). American Mathematical Society LEARNING ® MEDIA MATHSCINET ONLINE RESOURCES MATHEMATICS WASHINGTON, DC CONFERENCES MATHEMATICAL INCLUSION REVIEWS STUDENTS MENTORING PROFESSION GRAD PUBLISHING STUDENTS OUTREACH TOOLS EMPLOYMENT MATH VISUALIZATIONS EXCLUSION TEACHING CAREERS MATH STEM ART REVIEWS MEETINGS FUNDING WORKSHOPS BOOKS EDUCATION MATH ADVOCACY NETWORKING DIVERSITY blogs.ams.org Notices of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 FEATURED 684684 718 26 678 Gravitational Waves The Graduate Student The Travel Ban: Affected Introduction Section Mathematicians Tell Their by Christina Sormani Karen E. Smith Interview Stories How the Green Light was Given for by Laure Flapan Gravitational Wave Research by Alexander Diaz-Lopez, Allyn by C. Denson Hill and Paweł Nurowski WHAT IS...a CR Submanifold? Jackson, and Stephen Kennedy by Phillip S. Harrington and Andrew Gravitational Waves and Their Raich Mathematics by Lydia Bieri, David Garfinkle, and Nicolás Yunes This season of the Perseid meteor shower August 12 and the third sighting in June make our cover feature on the discovery of gravitational waves -

Hilbert Constance Reid

Hilbert Constance Reid Hilbert c COPERNICUS AN IMPRINT OF SPRINGER-VERLAG © 1996 Springer Science+Business Media New York Originally published by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc in 1996 All rights reserved. No part ofthis publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Library ofCongress Cataloging·in-Publication Data Reid, Constance. Hilbert/Constance Reid. p. Ctn. Originally published: Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag, 1970. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-387-94674-0 ISBN 978-1-4612-0739-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4612-0739-9 I. Hilbert, David, 1862-1943. 2. Mathematicians-Germany Biography. 1. Title. QA29.HsR4 1996 SIO'.92-dc20 [B] 96-33753 Manufactured in the United States of America. Printed on acid-free paper. 9 8 7 6 543 2 1 ISBN 978-0-387-94674-0 SPIN 10524543 Questions upon Rereading Hilbert By 1965 I had written several popular books, such as From liro to Infinity and A Long Way from Euclid, in which I had attempted to explain certain easily grasped, although often quite sophisticated, mathematical ideas for readers very much like myself-interested in mathematics but essentially untrained. At this point, with almost no mathematical training and never having done any bio graphical writing, I became determined to write the life of David Hilbert, whom many considered the profoundest mathematician of the early part of the 20th century. Now, thirty years later, rereading Hilbert, certain questions come to my mind. -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach the Arithmetic of Fields

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 05/2009 The Arithmetic of Fields Organised by Moshe Jarden (Tel Aviv) Florian Pop (Philadelphia) Leila Schneps (Paris) February 1st – February 7th, 2009 Abstract. The workshop “The Arithmetic of Fields” focused on a series of problems concerning the interplay between number theory, arithmetic and al- gebraic geometry, Galois theory, and model theory, such as: the Galois theory of function fields / covers of varieties, rational points on varieties, Galois co- homology, local-global principles, lifting/specializing covers of curves, model theory of finitely generated fields, etc. Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 12E30. Introduction by the Organisers The sixth conference on “The Arithmetic of Fields” was organized by Moshe Jar- den (Tel Aviv), Florian Pop (Philadelphia), and Leila Schneps (Paris), and was held in the week February 1–7, 2009. The participants came from 14 countries: Germany (14), USA (11), France (7), Israel (7), Canada (2), England (2), Austria (1), Brazil (1), Hungary (1), Italy (1), Japan (1), South Africa (1), Switzerland (1), and The Netherlands (1). All together, 51 people attended the conference; among the participants there were thirteen young researchers, and eight women. Most of the talks concentrated on the main theme of Field Arithmetic, namely Galois theory and its interplay with the arithmetic of the fields. Several talks had an arithmetical geometry flavour. All together, the organizers find the blend of young and experienced researchers and the variety of subjects covered very satisfactory. The Arithmetic of Fields 3 Workshop: The Arithmetic of Fields Table of Contents Moshe Jarden New Fields With Free Absolute Galois Groups ...................... -

Bryn Mawr College Undergraduate Catalog

2015–16 Bryn Mawr College Undergraduate Catalog Bryn Mawr College does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, age or disability in the administration of its educational policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other College-administered programs, or in its employment practices. In conformity with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, it is also the policy of Bryn Mawr College not to discriminate on the basis of sex in its educational programs, activities or employment practices. The admission of only women in the Undergraduate College is in conformity with a provision of the Act. Inquiries regarding compliance with this legislation and other policies regarding nondiscrimination may be directed to the Equal Opportunity Officer, who administers the College’s procedures, at 610-526-5275. All information in this catalog is subject to change without notice. © 2015 Bryn Mawr College TABLE OF CONTENTS Admission 19 Billing, Payment, and Financial Aid 23 2015–16 Academic Calendars 3 Student Financial Services 23 Contact and Website Information 4 Costs of Education 23 Billing and Payment Due Dates 23 About Bryn Mawr College 5 Refund Policy 23 The Mission of Bryn Mawr College 5 When a Student Withdraws 24 A Brief History of Bryn Mawr College 5 Financial Aid 25 College as Community 7 Required Forms and Instructions 26 Geographical Distribution of Students 8 Loan Funds 27 Scholarship Funds 29 Libraries and Educational Resources 10 Academic Program 38 Libraries 10 -

Early History of the Riemann Hypothesis in Positive Characteristic

The Legacy of Bernhard Riemann c Higher Education Press After One Hundred and Fifty Years and International Press ALM 35, pp. 595–631 Beijing–Boston Early History of the Riemann Hypothesis in Positive Characteristic Frans Oort∗ , Norbert Schappacher† Abstract The classical Riemann Hypothesis RH is among the most prominent unsolved prob- lems in modern mathematics. The development of Number Theory in the 19th century spawned an arithmetic theory of polynomials over finite fields in which an analogue of the Riemann Hypothesis suggested itself. We describe the history of this topic essentially between 1920 and 1940. This includes the proof of the ana- logue of the Riemann Hyothesis for elliptic curves over a finite field, and various ideas about how to generalize this to curves of higher genus. The 1930ies were also a period of conflicting views about the right method to approach this problem. The later history, from the proof by Weil of the Riemann Hypothesis in charac- teristic p for all algebraic curves over a finite field, to the Weil conjectures, proofs by Grothendieck, Deligne and many others, as well as developments up to now are described in the second part of this diptych: [44]. 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification: 14G15, 11M99, 14H52. Keywords and Phrases: Riemann Hypothesis, rational points over a finite field. Contents 1 From Richard Dedekind to Emil Artin 597 2 Some formulas for zeta functions. The Riemann Hypothesis in characteristic p 600 3 F.K. Schmidt 603 ∗Department of Mathematics, Utrecht University, Princetonplein 5, 3584 CC -

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction To

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Springer-V erlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH Richard Courant • Fritz John Introd uction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Reprint of the 1989 Edition Springer Originally published in 1965 by Interscience Publishers, a division of John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Reprinted in 1989 by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. Mathematics Subject Classification (1991): 26-XX, 26-01 Cataloging in Publication Data applied for Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Courant, Richard: Introduction to calcu1us and analysis / Richard Courant; Fritz John.- Reprint of the 1989 ed.- Berlin; Heidelberg; New York; Barcelona; Hong Kong; London; Milan; Paris; Singapore; Tokyo: Springer (Classics in mathematics) VoL 1 (1999) ISBN 978-3-540-65058-4 ISBN 978-3-642-58604-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-58604-0 Photograph of Richard Courant from: C. Reid, Courant in Gottingen and New York. The Story of an Improbable Mathematician, Springer New York, 1976 Photograph of Fritz John by kind permission of The Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York ISSN 1431-0821 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved. whether the whole or part of the material is concemed. specifically the rights of trans1ation. reprinting. reuse of illustrations. recitation. broadcasting. reproduction on microfilm or in any other way. and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted onlyunder the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9.1965. in its current version. and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are Iiable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. -

GSAS Catalog 2019-20

BRYN MAWR COLLEGE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES Catalog and Handbook This handbook contains information about the M. A. and Ph. D. requirements that pertains to all students enrolled in GSAS. Individual programs also have their own policies concerning graduate study. It is the student’s responsibility to know these program- specific requirements, and the responsibility of the faculty to share them with students in a clear and timely manner. 2019-2020 GSAS 2019-20 Academic Calendar This calendar provides a schedule for students and faculty to meet important deadlines specified in the Faculty Rules governing the M.A. and Ph.D. degrees. Fall 2019 Aug. 28 Orientation for all new GSAS students and first-time TAs (required) Aug. 29 President's reception for new graduate students Aug. 30 Last date to waive or accept Bryn Mawr Health Insurance Aug. 30- Online Registration through BIONIC for new GSAS Sept. 11 students for Semester I Sept. 3 First day of classes TBD GSAS Welcome Back Picnic Sept. 11 Last date to drop or add a course in Semester 1 Sept. 27 Application for M.A. Candidacy for the Dec. 15 degree is due Oct. 1 Deadline to change incomplete grades to S or U from academic year 2018-19 Oct. 11 Deadline to schedule Preliminary Examinations for Semester 1 Oct. 11 Deadline for submitting Ph.D. dissertations for the Dec.15 degree from students in ARCH, Classics, & HART. Dissertations must be deposited in GSAS Office by 4 pm Oct. 12-20 Fall Break Oct. 31 Deadline for graduate student applications for reimbursement of travel and research expenses for the current academic year Deadline for submitting Ph.D. -

Volume 9, Number 4 N~NSLETTER July-August 1979 PRESIDENT' S REPORT Duluth Meeting. the 1979 AWM Summer Meeting Will Be Held at T

Volume 9, Number 4 N~NSLETTER July-August 1979 **************************************************************************************** PRESIDENT' S REPORT Duluth meeting. The 1979 AWM summer meeting will be held at the joint mathematics meetings at the University of Minnesota in Duluth. All of our scheduled events will be on Thursday, August 23. They are: a panel discussion at 4 p.m. in Bohannon 90 on "Math education: a feminist per- spective." Moderator: Judy Roltman, University of Kansas Panelists: Lenore Blum, Mills College Deborah Hughes Hallett, Harvard University Diane Resek, San Francisco State University We also hope to have materials to present from a re-entry program in the De Anza Community College District (California). a business meeting at 5 p.m. in Bohannon 90 (following the panel). Agenda: new by-laws Goal: to get a members' consensus on new by-laws to be voted on in the fall by mail ballot. a wine and cheese party at 8 p.m. in the lounge of the Kirby Student Center. There will also be an AWM table staffed throughout the meeting. Volunteers are needed to staff it - check with us when you come to the meetings. Come on by and visitl bring your friends too. Also in Duluth: the MAA's HedrIck Lectures will be presented by Mary Ellen Rudin of the Universlty of Wisconsin, Madison. By-laws. The by-laws will be written up by mld-July, and available from the AWM office. Suggestions and amendments are welcome. The procedure is that they will be presented at Duluth for amendment and non-blnding sense-of-the-meeting comments. -

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Individual Fates and Global Impact Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze princeton university press princeton and oxford Copyright 2009 © by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siegmund-Schultze, R. (Reinhard) Mathematicians fleeing from Nazi Germany: individual fates and global impact / Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-12593-0 (cloth) — ISBN 978-0-691-14041-4 (pbk.) 1. Mathematicians—Germany—History—20th century. 2. Mathematicians— United States—History—20th century. 3. Mathematicians—Germany—Biography. 4. Mathematicians—United States—Biography. 5. World War, 1939–1945— Refuges—Germany. 6. Germany—Emigration and immigration—History—1933–1945. 7. Germans—United States—History—20th century. 8. Immigrants—United States—History—20th century. 9. Mathematics—Germany—History—20th century. 10. Mathematics—United States—History—20th century. I. Title. QA27.G4S53 2008 510.09'04—dc22 2008048855 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 Contents List of Figures and Tables xiii Preface xvii Chapter 1 The Terms “German-Speaking Mathematician,” “Forced,” and“Voluntary Emigration” 1 Chapter 2 The Notion of “Mathematician” Plus Quantitative Figures on Persecution 13 Chapter 3 Early Emigration 30 3.1. The Push-Factor 32 3.2. The Pull-Factor 36 3.D. -

Abraham Robinson, 1918 - 1974

BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 83, Number 4, July 1977 ABRAHAM ROBINSON, 1918 - 1974 BY ANGUS J. MACINTYRE 1. Abraham Robinson died in New Haven on April 11, 1974, some six months after the diagnosis of an incurable cancer of the pancreas. In the fall of 1973 he was vigorously and enthusiastically involved at Yale in joint work with Peter Roquette on a new model-theoretic approach to diophantine problems. He finished a draft of this in November, shortly before he underwent surgery. He spoke of his satisfaction in having finished this work, and he bore with unforgettable dignity the loss of his strength and the fading of his bright plans. He was supported until the end by Reneé Robinson, who had shared with him since 1944 a life given to science and art. There is common consent that Robinson was one of the greatest of mathematical logicians, and Gödel has stressed that Robinson more than any other brought logic closer to mathematics as traditionally understood. His early work on metamathematics of algebra undoubtedly guided Ax and Kochen to the solution of the Artin Conjecture. One can reasonably hope that his memory will be further honored by future applications of his penetrating ideas. Robinson was a gentleman, unfailingly courteous, with inexhaustible enthu siasm. He took modest pleasure in his many honors. He was much respected for his willingness to listen, and for the sincerity of his advice. As far as I know, nothing in mathematics was alien to him. Certainly his work in logic reveals an amazing store of general mathematical knowledge. -

Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Department Of

Basilios Bessarion Mystras 1436 Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 Università di Padova 1444 Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Vittorino da Feltre Marsilio Ficino Cristoforo Landino Università di Padova 1416 Università di Firenze 1462 Theodoros Gazes Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Angelo Poliziano Florens Florentius Radwyn Radewyns Geert Gerardus Magnus Groote Università di Mantova 1433 Università di Mantova Università di Firenze 1477 Constantinople 1433 DepartmentThe Mathematics Genealogy Project of is a serviceMathematics of North Dakota State University and and the American Statistics Mathematical Society. Demetrios Chalcocondyles http://www.mathgenealogy.org/ Heinrich von Langenstein Gaetano da Thiene Sigismondo Polcastro Leo Outers Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Rudolf Agricola Thomas von Kempen à Kempis Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Accademia Romana 1452 Université de Paris 1363, 1375 Université Catholique de Louvain 1485 Università di Firenze 1493 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1478 Mystras 1452 Jan Standonck Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Johannes von Gmunden Nicoletto Vernia Pietro Roccabonella Pelope Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Jean Tagault François Dubois Janus Lascaris Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Matthaeus Adrianus Alexander Hegius Johannes Stöffler Collège Sainte-Barbe 1474 Universität Basel 1477 Universität Wien 1406 Università di Padova Università di Padova Université Catholique de Louvain 1504, 1515 Université de Paris 1516 Università di Padova 1472 Università