SCHOOL ACCESS GRANTS FINAL REPORT Increasing Opportunities for Children and Youth to Participate in Critical Hours Programming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday, June 15, 2017

APPROVED MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES REGULAR BOARD MEETING HELD RVS EDUCATION CENTRE 2651 CHINOOK WINDS DR. SW AIRDRIE, ALBERTA THURSDAY, JUNE 15, 2017 TRUSTEES PRESENT: Chair, Ward 5 Colleen Munro Vice Chair, Ward 3 Todd Brand Ward 1 Norma Lang Ward 2 Bev LaPeare Ward 3 Sylvia Eggerer Ward 4 Helen Clease Ward 6 Fiona Gilbert TRUSTEES ABSENT WITH REGRETS: ADMINISTRATION PRESENT: Superintendent of Schools Greg Luterbach Associate Superintendent of Business and Darrell Couture Operations RECORDER: Executive Assistant Karen Dolynny CALL TO ORDER: Chair Colleen Munro called the meeting to order at 9:31a.m. REGULAR BOARD MEETING AGENDA #115-2017 MOTION BY TRUSTEE BEV LAPEARE : The Board of Trustees approves the June 15, 2017, Regular Board meeting agenda as presented. CARRIED IN CAMERA: #116-2017 MOTION BY TRUSTEE BEV LAPEARE : The Board of Trustees moves into an in-camera meeting at 9:32 a.m. CARRIED Board Chair Coleen Munro recessed the In-Camera meeting at 10:10 a.m. to move into the Regular Board meeting. Rocky View School Division No. 41 ___________________________ Chair – Board of Trustees MINUTES OF THE BOARD MEETING #117-2017 MOTION BY TRUSTEE NORMA LANG: The Board of Trustees approves the minutes of the June 1, 2017, Regular Board meeting as circulated. CARRIED EXEMPLARY PRACTICE: EXCELLENCE IN TEACHER/EDWIN PARR/POST-SECONDARY ACHIEVEMENTS Recognition of Post-Secondary Achievement Centered on the principle that building capacity increases the collective efficacy of a group to improve student learning, Rocky View Schools believes that educators have a responsibility to be both teachers and learners. In order to equip today’s learners with the critical competencies needed to succeed in tomorrow’s changing global society, educators first must understand the world that they are preparing them for. -

Arnprior District High School Arnprior, on St

Canadian Nuclear Society / Société Nucléaire Canadienne Page 1 of 6 CNS Geiger Kit Donations: (sorted by province, most recent) Bert Church High School Airdrie, AB George MacDougal High School Airdrie, AB Bishop Grandin High School Calgary, AB Bowness High School Calgary, AB Chestermere High School Calgary AB Dr. E. P. Scarlett High School Calgary AB Henry Wise Wood High School Calgary AB James Fowler High School Calgary, AB John G. Diefenbaker High School Calgary, AB Lord Beaverbrook High School Calgary, AB Sir Winston Churchill High School Calgary, AB Springbank Community High School Calgary, AB Camrose Composite High School Camrose, AB Bow Valley High School Cochrane, AB Cochrane High School Cochrane, AB Centre High School Edmonton, AB St. Laurent High School Edmonton, AB Parkland Composite High School Edson, AB Grande Cache Community HS Grand Cache, AB Nipisihkopahk Secondary School Hobbema, AB Kitscoty High School Kitscoty, AB Winston Churchill High School Lethbridge, AB Centre for Learning @ Home Okotoks, AB Foothills Composite High School Okotoks, AB Onoway Jr/Sr High School Onoway, AB Lindsay Thurber Comprehensive HS, Red Deer AB Salisbury Composite High School Sherwood Park, AB Strathcona Christian Academy Secondary Sherwood Park, AB Evergreen Catholic Outreach Spruce Grove, AB Memorial Composite High School Stony Plain, AB St. Mary’s Catholic High School Vegreville, AB J.R. Robson High School Vermilion, AB Blessed Sacrament Secondary School Wainwright, AB Pinawa Secondary School Pinawa, MB Bathurst High School Bathurst, NB # -

Mental Health Capacity Building Projects in Alberta, April 2015

Alberta Health – Mental Health Capacity Building Projects in Alberta April 2015 Education AHS Project MHCB Project Name Schools Grades Community School Division Zone Zone Bert Church High School 9/12 Airdrie Bow Valley High School 10/12 Cochrane Airdrie/ Mitford Middle School K-8 Stepping Stones to Mental Health Rocky View School Division No. 41 Zone 5 Calgary Chestermere WG Murdoch School 6/12 Crossfield George McDougall High School 9/12 Airdrie Chestermere High School 10/12 Chestermere Banff Elementary School K-6 Banff Banff/ Canadian Rockies Regional Division Right from the Start École Lawrence Grassi Middle School 4/8 Zone 5 Calgary Canmore Canmore No. 12 Elizabeth Rummel K-3 Sunrise Outreach School 6/12 Central School K-1 Brooks/ Innovations Project (schools as per Eastbrook Elementary School 2/6 Brooks Grasslands Regional Division No. 6 Zone 6 South Grasslands facebook page) Griffin Park School 2/6 Brooks Junior High School 7/9 École La Mosaïque K-6 École de la Source K-9 École La Rose Sauvage 7/12 Calgary École Notre Dame-de-la Paix K-6 Calgary Greater Southern Separate Public Projet Appartenance École Terre des Jeunes K-6 Zone 5 Calgary Francophone Francophone Region #4 École Sainte-Marguerite-Bourgeoys K-12 École Notre-Dame des Vallées K-8 Cochrane École Francophone d'Airdrie K-12 Airdrie École Beausoleil K-7 Okotoks École Notre-Dame des Monts K-12 Canmore Almadina-Mountain View Elementary K-4 Transitions - A Wellness Campus Almadina School Society - Charter Calgary Calgary Zone 5 Calgary Empowerment Project (WEP) Almadina-Ogden Middle School School 5/9 Campus © 2015 Government of Alberta 1 Alberta Health – Mental Health Capacity Building Projects in Alberta April 2015 Calgary Islamic Private School K-12 Private Schools Phoenix Horizon Academy Private K-12 Forest Lawn High School 10/12 Annie Gale Junior High 7/9 Ernest Morrow Junior High 6/9 Calgary Board of Education Lester B. -

Langdon Junior/Senior High School Construction Update 2021-2023

Ward Two Trustee Report MARCH / APRI L/ MAY 2020 Langdon Junior/Senior High School Construction Update ▪ A conceptual design for our newest Ward 2 School was completed at the end of May. ▪ The province confirmed, in late April, that they will provide funding for construction to begin in the fall of 2021. ▪ Potential date for the school to open is September 2024. 2021-2023 Capital Plan Priorities ▪ Trustees approved RVS’ 2021-2023 Capital Plan Priorities and directed administration to submit to Alberta Education by April 1, 2020. ▪ RVS’ number one priority for the 2021 budget year is to increase the size of Bow Valley High School’s existing building in order to address an anticipated utilization rate of 112 per cent. ▪ The second and third 2021 capital priorities are to build new schools in both Airdrie (K – Gr. 9) and Cochrane (K – Gr. 5). General Contractors Selected for Indus School ▪ Trustees awarded Westcor Construction Inc. a contract for the full renovation of Indus School. ▪ Trustees awarded Great Northern Plumbing Inc. a contract to complete a Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) system upgrade at Beiseker Community School. ▪ Trustees awarded Ainsworth Inc. two contracts to complete HVAC system upgrades at W.G. Murdoch School and Cochrane High School. ▪ Trustees awarded MJS Mechanical LTD a contract to complete a HVAC system upgrade at A.E. Bowers School. Schools Designated for New Chestermere Communities ▪ Effective September 2020, English and French Immersion students residing in Chestermere’s new communities of Chelsea and Dawson’s Landing will be designated to East Lake School, Chestermere Lake Middle School and Chestermere High School. -

Arnprior District High School Arnprior, on St

Canadian Nuclear Society / Société Nucléaire Canadienne Page 1 of 6 CNS Geiger Kit Donations: (sorted by province, most recent) Bert Church High School Airdrie, AB George MacDougal High School Airdrie, AB Bishop Grandin High School Calgary, AB Bowness High School Calgary, AB Chestermere High School Calgary AB Dr. E. P. Scarlett High School Calgary AB Henry Wise Wood High School Calgary AB James Fowler High School Calgary, AB John G. Diefenbaker High School Calgary, AB Lord Beaverbrook High School Calgary, AB Sir Winston Churchill High School Calgary, AB Springbank Community High School Calgary, AB Camrose Composite High School Camrose, AB Bow Valley High School Cochrane, AB Cochrane High School Cochrane, AB Centre High School Edmonton, AB St. Laurent High School Edmonton, AB Parkland Composite High School Edson, AB Grande Cache Community HS Grand Cache, AB Nipisihkopahk Secondary School Hobbema, AB Kitscoty High School Kitscoty, AB Winston Churchill High School Lethbridge, AB Centre for Learning @ Home Okotoks, AB Foothills Composite High School Okotoks, AB Onoway Jr/Sr High School Onoway, AB Lindsay Thurber Comprehensive HS, Red Deer AB Salisbury Composite High School Sherwood Park, AB Strathcona Christian Academy Secondary Sherwood Park, AB Evergreen Catholic Outreach Spruce Grove, AB Memorial Composite High School Stony Plain, AB St. Mary’s Catholic High School Vegreville, AB J.R. Robson High School Vermilion, AB Blessed Sacrament Secondary School Wainwright, AB Pinawa Secondary School Pinawa, MB Bathurst High School Bathurst, NB # -

Grant Macewan Fonds for ADDITIONAL ARCHIVAL MATERIAL CLICK HERE

Grant MacEwan fonds FOR ADDITIONAL ARCHIVAL MATERIAL CLICK HERE https://searcharchives.ucalgary.ca/grant-macewan-fonds GRANT MacEWAN fonds ACCESSION NO. 74/74.7 The Grant MacEwan Fonds Accession No. 74/74.7 CORRESPONDENCE ....................................................................................................................................... 2 MANUSCRIPTS ........................................................................................................................................... 167 Judaism Pamphlet Series ...................................................................................................................... 178 Briefs for Public Hearings regarding ..................................................................................................... 180 Page 2 GRANT MacEWAN fonds ACCESSION NO. 74/74.7 FILE TITLE DATES BOX/FILE CORRESPONDENCE Unidentified correspondence [19--] 1.1 _____, Anahareo(?) 1972 1.2 _____, Avory 1970 1.3 _____, Barbara 1975 1.4 _____, Bev 1976-1977 1.5 _____, Dorine [19--] 1.6 _____, Dorothy 1972 1.7 _____, Jim 1976-1977 1.8 _____, Gladys 1971 1.9 _____, Merle 1966 1.10 Page 3 GRANT MacEWAN fonds ACCESSION NO. 74/74.7 FILE TITLE DATES BOX/FILE _____, Pat 1975-1977 1.11 _____, Paul 1975 1.12 _____, Thomas 1976 1.13 4-H Foundation of Alberta 1974, 1977 1.14 22nd Challenger Rover Crew 1974 1.15 34th Cub, Scout and Venturer Group (Calgary, 1975 1.16 Alta.) 61st Boy Scout Group (Calgary, Alta.) 1966 1.17 Access 1976 1.18 Age of Enlightenment Capitals Project 1977 1.19 Agriculture -

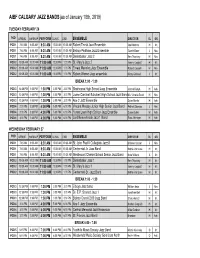

Copy of 2019 AIBF Master Schedule Jan 18 for Distribution

AIBF CALGARY JAZZ BANDS (as of January 18th, 2019) TUESDAY FEBRUARY 26 POD ARRIVE WARMUP PERFORM CLINIC END ENSEMBLE DIRECTOR CL GR POD 1 7:45 AM 8:00 AM 8:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM Robert Thirsk Jazz Ensemble Joel Abrams H Int POD 1 7:45 AM 8:00 AM 8:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM Bishop Pinkham Jazz Ensemble Gareth Bane J Nov POD 1 7:45 AM 8:00 AM 8:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM Diefenbaker Jazz 2 Ken Thackrey H Nov POD 2 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 12:30 PM 1:00 PM St. Mary's Jazz 2 Jeremy Legault H Int POD 2 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 12:30 PM 1:00 PM Ernest Manning Jazz Ensemble Robert Cesselli H Nov POD 2 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 12:30 PM 1:00 PM Robert Warren Jazz ensemble Kirsty Gilliland J Int BREAK 1:00 - 1:30 POD 3 12:30 PM 1:00 PM 1:30 PM 3:00 PM 3:30 PM Strathcona High School Jazz Ensemble Jerrold Dubyk H Adv POD 3 12:30 PM 1:00 PM 1:30 PM 3:00 PM 3:30 PM Joane Cardinal-Schubert High School Jazz Band Ms. Victoria Scott H Nov POD 3 12:30 PM 1:00 PM 1:30 PM 3:00 PM 3:30 PM Abe 2 Jazz Ensemble Dylan Martin H Adv POD 4 3:00 PM 3:30 PM 4:00 PM 5:30 PM 6:00 PM Vincent Massey Junior High Senior Jazz Band Patrick Steeves J Nov POD 4 3:00 PM 3:30 PM 4:00 PM 5:30 PM 6:00 PM Forest Lawn High School Jazz Ensmble Duane Lebo H Adv POD 4 3:00 PM 3:30 PM 4:00 PM 5:30 PM 6:00 PM Lord Beaverbrook Jazz1 Band Ross McIntyre H Adv WEDNESDAY FEBRUARY 27 POD ARRIVE WARMUP PERFORM CLINIC END ENSEMBLE DIRECTOR CL GR POD 1 7:45 AM 8:00 AM 8:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM St. -

Happy St. Patrick's Day!

MARCH 2020 DELIVERED MONTHLY TO 2,300 HOUSEHOLDS ROSS-CHARACTER THE OFFICIAL ROSSCARROCK COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER HAPPY ST. PATRICK’S DAY! COMMUNITY PANTRY NOW OPEN! VOLUNTEERS NEEDED! June 13 and 14 Deerfoot Inn & Casino One of the most impactful things you can do for the Rosscarrock Community Association is to volunteer for our casino. No experience necessary, as all training is provided. All volunteers are entitled to a complimentary hot meal while working, and refreshments and snacks are also provided. Please contact [email protected] for more information. Ross-Character - Designed, manufactured, and delivered monthly to 2,300 households by: GREAT NEWS MEDIA Magazine Editors Alexa Takayama Jocelyn Taylor [email protected] Design | Graphics Joanne Bergen Print & Digital Marina Litvak Freddy Meynard TARGETED Erica Morton MARKETING Carolina Tatar BY COMMUNITY Advertising Sales Sam Brown Cindy DeJager Brittany Duval Carol Ann Rhyno [email protected] | 403 720 0762 5 Excellent Reasons to Advertise in Community Newsletter Magazines 1. Top of Mind Brand Awareness: Consistent advertising leads to increased sales. Companies maintain and gain market share when community residents are consistently reminded of their brands. 2. Payback: Community residents trust, and call businesses that advertise in their community magazines. 3. High Readership: 68% female | Even distribution of Millennial, Gen X, and Baby Boomer readers 4. Cost Effective:With advertising rates as low as $0.01 cent per household, advertising in our community maga- zines -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 475 605 SO 034 686 TITLE High School Social Studies Needs Assessment Report. INSTITUTION Alberta Learning, Edmonton. Curriculum Standards Branch. ISBN ISBN-0-7785-2542-2 PUB DATE 2002-09-00 NOTE 162p.; Alberta Learning, Curriculum Branch, 6th Floor, East Devonian Building, 11160 Jasper Avenue, Edmonton, AB T5K OL2. Tel: 780-427-2984; Fax: 780-422-3745; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.learning.gov.ab.ca/. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Assessment; Foreign Countries; High Schools; *Needs Assessment; *Program Development; Questionnaires; Secondary Education; *Social Studies; Surveys IDENTIFIERS *Alberta ABSTRACT In 2001, Canada's Alberta Learning embarked on development of a new provincial high school social studies program by conducting a province- wide needs assessment survey. Its purpose was to gather data, input, and suggestions to guide curriculum developers in the development of the new program. A needs assessment questionnaire was the primary tool for gathering qualitative and quantitative data from educational partners and stakeholders. During the needs assessment process, respondents submitted 1526 questionnaires, including feedback from Aboriginal and Francophone respondents. This report enumerates the results, summarizing the areas of concern surrounding the existing high school social studies program, as identified by questionnaire respondents and consultation participants. The report cites as areas of concern: program content; program rationale; curriculum overlap; quantity of curricular content; and skills and processes. It also provides general advice and input provided by questionnaire respondents, and consultation participants, regarding breadth of coverage, depth of coverage, program focus, program content, skill development, two course sequences, learning and teaching resources, and stakeholder participation. -

Alberta Distance Learning Centre Annual Education Results Report

AAllbbeerrttaa DDiissttaannccee LLeeaarrnniinngg CCeennttrree AAnnnnuuaall EEdduuccaattiioonn RReessuullttss RReeppoorrtt November 27, 2009 Annual Education Results Report (ADLC) Approved by Board Motion #5045/11/09 Last Revision: Nov 27, 2009 2 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 SECTION 1 ANNUAL EDUCATIONAL RESULTS REPORTING .................................................................................... 5 1.1 ACCOUNTABILITY STATEMENT 5 1.2 ADLC ANNUAL EDUCATION RESULTS REPORT DISTRIBUTION 5 SECTION 2 ALBERTA DISTANCE LEARNING CENTRE PROFILE ............................................................................ 6 2.1 FOUNDATION STATEMENTS 6 2.2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 9 2.3 OVERVIEW OF EDUCATION SERVICES IN ALBERTA DISTANCE LEARNING CENTRE 10 2.3.1 PARTNERSHIPS IN DELIVERY 10 2.3.2 PARTNERSHIPS IN DEVELOPMENT 14 2.3.3 INNOVATIVE DISTRIBUTED LEARNING RESOURCES 15 2.3.4 ACCESSORY PROGRAMS 15 2.3.5 SUMMARY 15 SECTION 3 ALBERTA DISTANCE LEARNING CENTRE HIGHLIGHTS, 2008-2009 ............................................... 16 3.1 SUMMARY OF ACCOMPLISHMENTS 16 3.2 REGIONAL OFFICES 16 3.2.1 ADLC EDMONTON 16 3.2.2 ADLC CALGARY 17 3.2.3 ADLC LETHBRIDGE 18 3.3 FRANCOPHONE PROGRAM 19 3.4 ALBERTA INITIATIVE FOR SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT (AISI) 22 3.5 FIRST NATION MÉTIS AND INUIT (FNMI) 22 3.6 TECHNOLOGY SERVICES 22 SECTION 4 PERFORMANCE MEASURE RESULTS ..................................................................................................... -

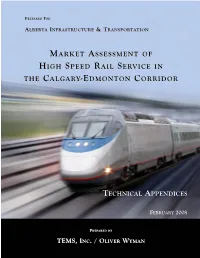

Market Assessment of High Speed Rail Service in the Calgary-Edmonton Corridor Appendices

PREPARED FOR ALBERTA INFRASTRUCTURE & TRANSPORTATION MMARKETARKET AASSESSMENTSSESSMENT OFOF HHIGHIGH SSPEEDPEED RRAILAIL SSERERVICEVICE ININ THETHE CCALALGGARARYY-E-EDMONTDMONTONON CCORRIDORORRIDOR TECHNICAL APPENDICES FEBRUARY 2008 PREPARED BY TEMS, INCNC. / OLIVERLIVER WYMANYMAN Market Assessment of High Speed Rail Service in the Calgary—Edmonton Corridor Appendices This report was prepared by Transportation Economics & Management Systems, Inc. (TEMS) for the Government of Alberta. The report’s contents do not necessarily constitute the official policy and position of the Government of Alberta. TEMS, Inc. / Oliver Wyman February 2008 ii Market Assessment of High Speed Rail Service in the Calgary—Edmonton Corridor Appendices Appendices A Fundamentals of Demand Modeling A.1 COMPASS™ Demand Model The COMPASS™ Model System is a flexible multimodal demand-forecasting tool that provides comparative evaluations of alternative socioeconomic and network scenarios. It also allows input variables to be modified to test the sensitivity of demand to various parameters such as elasticities, values of time, and values of frequency. This section describes in detail the model methodology and process using in the present study. A.1.1 Description of the COMPASS™ Model System The COMPASS™ Model is structured on three principal models: Total Demand Model, Hierarchical Modal Split Model, and Induced Demand Model. For this study, these three models were calibrated separately for two trip purposes, i.e., Business and Other (commuter, personal, and social). Moreover, since the behaviour of short-distance trip making is significantly different from long-distance trip making, the database was segmented by distance, and independent models were calibrated for both long and short-distance trips. For each market segment, the models were calibrated on origin-destination trip data, network characteristics, and base year socioeconomic data. -

Calgary RSCC

2013 Calgary Regional Skills Canada Competition Results March 23, 2013 Rank Competitor School Auto Service - JUNIOR 1 Ben Clutterbuck Foothills Composite High School 2 Troy Pruitt Bowness High School 3 Taylor Fielding Forest Lawn High School Safety Award Kemlyn Gardner Forest Lawn High School Competitors (Listed alphabetically by school name) Jake Sill Bishop Grandin High School Ryle Bothe Dr. E.P. Scarlett High School Daniel Bialkowski Jack James High School Auto Service - SENIOR *1 Vlad Butoi Bishop Grandin High School *2 Jonathan Wickstrand Jack James High School *3 Mark McDonald Forest Lawn High School *4 Jared Rybachuk St. Francis High School Safety Award Ryan Bugye Sir Winston Churchill High School Competitors (Listed alphabetically by school name) Jessie Richelhoff Bishop Grandin High School Tyler Grenier Bishop O'Byrne High School Mitchell Bery Foothills Composite High School * Moving onto the Provincial Skills Canada Competition Culinary Arts *1 Ross Bowles CT Centre *2 Danica De Aza Bishop O'Byrne High School *3 Nolan Moskaluk Bishop Grandin High School *4 & Safety Award Peter Nowicki St. Timothy Jr. Sr. School Competitors (Listed alphabetically by school name) Stefan Pacheco Bert Church High School Alexis Dela Cruz Bishop McNally High School Zachary Ramdhanie Bishop McNally High School Adam Strong Bowness High School Clotilde Boiral Dr. E.P. Scarlett High School Emma Banyard Foothills Composite High School Daniel Tang Forest Lawn High School Justis Edwards Highwood School Ricky Langlands Jack James High School Taegan Lloyd