ECON 3240 American Factory Workers in Chinese Factory Spring 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

\203E\203F\203U\203T\203C\203G\203A\203B\203V\203\215\201[\203H\227Pultimate Float Flat Patterned.Xls

FIC リファレンスリスト F フロート 、、、フラット 、、、パターンドガラス (((111///333))) フロートブースト 納入年 納入先 国名 システム プロセス 1992 Ford Motor Co. U.S.A. 4 Zone System : 5250kVA Float- High Iron Plant Shutdown 1993 Pilkington S.I.V. Italy 4 Zone System : 5500kVA Float- High Iron & Incr. Clear 2nd Campaign 1993 Ford Motor Co. U.S.A. 3 Zone System : 3000kVA Float- High Iron 1994 Glaverbel Belgium 3 Zone System : 5000kVA Float- High Iron 1996 Ford Motor Co. U.S.A. 3 Zone System : 3000kVA Float- High Iron 2nd Campaign 1996 Sisecam Turkey 2 Zone System : 3500kVA Float- High Iron & Incr. Clear 1997 NEG Japan Custom System Special Float Project - PDP * 1997 Kumgang Chemical Korea 3 Zone System : 3500kVA Float- High Iron 2nd Campaign 1998 Ford Motor Co. U.S.A. 3 Zone System : 3000kVA Float- High Iron * 1998 Guardian Ind. U.S.A. 2 Zone System : 4500kVA Float- High Iron & Incr. Clear 2nd Campaign 1999 Nippon Sheet Glass Japan Model Study only: 6350kVA Float - Boost Project 3 Zone System 2000 Kumgang Chemical Korea 3 Zone System : 3500kVA Float- High Iron 2001 Jiangsu Farun China 1 Zone System : 1800kVA Float- High Iron * 2001 TGI Kunshan China 1 Zone System : 1800kVA Float- High Iron & Incr. Clear 2001 TGI Kunshan China 2 Zone System : 4500kVA Increased Clear 2002 Jiangsu Farun China 2 Zone System : 3000kVA Float- High Iron & Incr. Clear 2002 Sisecam Turkey 4 Zone System : 4400kVA Float- High Iron & Incr. Clear 2003 Jiangsu Farun China 2 Zone System : 3500kVA Float- High Iron & Incr. Clear 2004 TGI Chengdu China 2 Zone System : 3100kVA Increased Clear 2004 TGI Huanan China 2 Zone System : 3100kVA Increased Clear * 2004 TGI Kunshan China Extra Zone added 2004 Hebei Yingxin China 1 Zone System : 1800kVA Improved Quality & Incr. -

Julia Reichert and the Work of Telling Working-Class Stories

FEATURES JULIA REICHERT AND THE WORK OF TELLING WORKING-CLASS STORIES Patricia Aufderheide It was the Year of Julia: in 2019 documentarian Julia Reichert received lifetime-achievement awards at the Full Frame and HotDocs festivals, was given the inaugural “Empowering Truth” award from Kartemquin Films, and saw a retrospec- tive of her work presented at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (The International Documentary Association had already given her its 2018 award.) Meanwhile, her newest work, American Factory (2019)—made, as have been all her films in the last two decades, with Steven Bognar—is being championed for an Academy Award nomination, which would be Reichert’s fourth, and has been picked up by the Obamas’ new Higher Ground company. A lifelong socialist- feminist and self-styled “humanist Marxist” who pioneered independent social-issue films featuring women, Reichert was also in 2019 finishing another film, tentatively titled 9to5: The Story of a Movement, about the history of the movement for working women’srights. Yet Julia Reichert is an underrecognized figure in the contemporary documentary landscape. All of Reichert’s films are rooted in Dayton, Ohio. Though periodically rec- ognized by the bicoastal documentary film world, she has never been a part of it, much like her Chicago-based fellow Julia Reichert in 2019. Photo by Eryn Montgomery midwesterners: Kartemquin Films (Gordon Quinn, Steve James, Maria Finitzo, Bill Siegel, and others) and Yvonne 2 The Documentary Film Book. She is absent entirely from Welbon. 3 Gary Crowdus’s A Political Companion to American Film. Nor has her work been a focus of very much documentary While her earliest films are mentioned in many texts as scholarship. -

The BG News February 13, 1987

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-13-1987 The BG News February 13, 1987 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 13, 1987" (1987). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4620. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4620 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Spirits and superstitions in Friday Magazine THE BG NEWS Vol. 69 Issue 80 Bowling Green, Ohio Friday, February 13,1987 Death Funding cut ruled for 1987-88 Increase in fees anticipated suicide by Mike Amburgey said. staff reporter Dalton said the proposed bud- get calls for $992 million Man kills wife, The Ohio Board of Regents statewide in educational subsi- has reduced the University's dies for 1987-88, the same friend first instructional subsidy allocation amount funded for this year. A for 1987-88 by $1.9 million, and 4.7 percent increase is called for by Don Lee unless alterations are made in in the academic year 1988-89 Governor Celeste's proposed DALTON SAID given infla- wire editor budget, University students tionary factors, the governor's could face at least a 25 percent budget puts state universities in The manager of the Bowling instructional fee increase, a difficult place. -

The English Factory Novel

1 THE ENGLISH FACTORY NOVEL BY LENA JOSEPHINE MYERS A. B. University of Illinois, 1913 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 19 18 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/englishfactorynoOOmyer_0 . ^\^% UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL 19liT I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION RY £u*^. ^kytsitL ENTITLED 7L-/Jll, BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR OF CAyA THE DEGREE /frltuA^ M(// In Charge of Thesis Head of Department Recommendation concurred in* — Committee on Final Examination* *Required for doctor'* degree but not for master's 408302 I The Table of Contents Introduction p«l-2 Chapter I A Resume of the English Factory Hovel p. 3 - 70 Chapter II The Relation of the Factory Novel to Its Age (a) A Brief Summary of the Social and Political Movements of the Period p. 71- 75 (b) The Historical Development of the Factory Novel p. 75- 78 (c) The Influence of the Factory Novel on Social Conditions p. 78- 92 (d) The Relation of the Factory Novel to Contem- porary Literature p. 92- 97 Chapter III The Characteristics and Problems of the Factory Novel p. 98 -112 Chapter IV The Factory Novel as a Work of Art Its Rank and Value p. 113-123 Conclusion p. 124-129 Bibliography A. English Novels Dealing with Factories p. 130 B. A Suggested List of American Novels Dealing with Fac- tories and Kindred Subjects p. -

Glazing Systems Intelligence Service

Global light vehicle OE glazing market- forecasts to 2029 April 2015 SAMPLE Usage and copyright statement A single-user licenced publication is provided for individual use only. Therefore this publication, or any part of it, may not be copied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or be transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of Aroq Limited. A multi-user licence edition can be freely and legally shared with your colleagues. This agreement includes sharing electronically via your corporate intranet or the making of physical copies for your company library. Excluded from this agreement is sharing any part of this publication with, or transmitting via any means to, anybody outside of your company. This content is the product of extensive research work. It is protected by copyright under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The authors of Aroq Limited's research are drawn from a wide range of professional and academic disciplines. The facts within this study are believed to be correct at the time of publication but cannot be guaranteed. All information within this study has been reasonably verified to the author’s and publisher’s ability, but neither accept responsibility for loss arising from decisions based on this report. © 2015 All content copyright Aroq Limited. All rights reserved. If you would like to find out about our online multi-user services for your team or organisation, please contact: Mike Chiswell Senior QUBE Business Manager Tel: +44 (0)1527 573 608 Toll free from US: 1-866-545-5878 Email: [email protected] http://wwwS.just-auto.com/qube AMPLE April 2015 Page 2 This a sample PDF. -

Exhibiting Warhols's Screen Tests

1 EXHIBITING WARHOL’S SCREEN TESTS Ian Walker The work of Andy Warhol seems nighwell ubiquitous now, and its continuing relevance and pivotal position in recent culture remains indisputable. Towards the end of 2014, Warhol’s work could be found in two very different shows in Britain. Tate Liverpool staged Transmitting Andy Warhol, which, through a mix of paintings, films, drawings, prints and photographs, sought to explore ‘Warhol’s role in establishing new processes for the dissemination of art’.1 While, at Modern Art Oxford, Jeremy Deller curated the exhibition Love is Enough, bringing together the work of William Morris and Andy Warhol to idiosyncratic but striking effect.2 On a less grand scale was the screening, also at Modern Art Oxford over the week of December 2-7, of a programme of Warhol’s Screen Tests. They were shown in the ‘Project Space’ as part of a programme entitled Straight to Camera: Performance for Film.3 As the title suggests, this featured work by a number of artists in which a performance was directly addressed to the camera and recorded in unrelenting detail. The Screen Tests which Warhol shot in 1964-66 were the earliest works in the programme and stood, as it were, as a starting point for this way of working. Fig 1: Cover of Callie Angell, Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests, 2006 2 How they were made is by now the stuff of legend. A 16mm Bolex camera was set up in a corner of the Factory and the portraits made as the participants dropped by or were invited to sit. -

History Overview Detailed 2020-2021 Tri 2

TRIMESTERTRIMESTER 2 HISTORYHISTORY OVERVIEWOVERVIEW 2020-2021 1/4-1/4-1/1/77 The Constitution Date 1787 Themes Rise and Fall of Empires and Nations Trade and Commerce Readings 1/4-5 Hist US V3 Ch 35, 36 Shhh! p 7-26 1/6-7 Hist US V3 Ch 37, 38 Shhh! p 28-44 1/11-12 Hist US V3 Ch 39, 40 Who Was Geo Washington? pp 1-21 Founding Mothers – Mrs. Jay Story of George Washington Ch 1-2 1/13-14 Hist US V3 Ch 41, 42 Who Was Geo Washington? pp 22-42 Story of George Washington Ch 3-4 BriefBrief OverviewOverview ofof AmericaAmerica inin thethe AftermathAftermath ofof thethe RevolutionaryRevolutionary WarWar The state of American affairs post-Revolutionary War: Congress and the states are in debt, and a postwar depression on the scale of the Great Depression of the 1930s exacerbates the troubles. Currency is losing value. Army vets are unpaid – given promissory notes that are worth little due to inflation. Vets sell their notes to put clothes on their backs and food in their mouths. Economic slump of the 1780s had many sources: • Massive quantities of property were destroyed in the war. • Because men were fighting in the war, they were unable to perform their regular jobs. Economic output fell. • Enslaved men, women, and children emancipated themselves by leaving with the British or simply running into forests and swamps. This was a financial loss to their enslavers. • Britain refused to allow Americans to trade with British sugar islands in the Caribbean – one of the American’s greatest income sources. -

National Conference

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE POPULAR CULTURE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN CULTURE ASSOCIATION In Memoriam We honor those members who passed away this last year: Mortimer W. Gamble V Mary Elizabeth “Mery-et” Lescher Martin J. Manning Douglas A. Noverr NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE POPULAR CULTURE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN CULTURE ASSOCIATION APRIL 15–18, 2020 Philadelphia Marriott Downtown Philadelphia, PA Lynn Bartholome Executive Director Gloria Pizaña Executive Assistant Robin Hershkowitz Graduate Assistant Bowling Green State University Sandhiya John Editor, Wiley © 2020 Popular Culture Association Additional information about the PCA available at pcaaca.org. Table of Contents President’s Welcome ........................................................................................ 8 Registration and Check-In ............................................................................11 Exhibitors ..........................................................................................................12 Special Meetings and Events .........................................................................13 Area Chairs ......................................................................................................23 Leadership.........................................................................................................36 PCA Endowment ............................................................................................39 Bartholome Award Honoree: Gary Hoppenstand...................................42 Ray and Pat Browne Award -

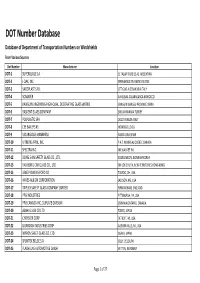

DOT Number Database Database of Department of Transportation Numbers on Windshields from Various Sources Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐1 SUPERGLASS S.A

DOT Number Database Database of Department of Transportation Numbers on Windshields From Various Sources Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐1 SUPERGLASS S.A. EL TALAR TIGRE BS.AS. ARGENTINA DOT‐2 J‐DAK, INC. SPRINGFIELD TN UNITED STATES DOT‐3 SACOPLAST S.R.L. OTTIGLIO ALESSANDRIA ITALY DOT‐4 SOMAVER AIN SEBAA CASABNLANCA MOROCCO DOT‐5 JIANGUIN JINGEHENG HIGH‐QUAL. DECORATING GLASS WORKS JIANGUIN JIANGSU PROVINCE CHINA DOT‐6 BASKENT GLASS COMPANY SINCAN ANKARA TURKEY DOT‐7 POLPLASTIC SPA DOLO VENEZIA ITALY DOT‐8 CEE BAILEYS #1 MONTEBELLO CA DOT‐9 VIDURGLASS MANBRESA BARCELONA SPAIN DOT‐10 VITRERIE APRIL, INC. P.A.T. MONREAL QUEBEC CANADA DOT‐11 SPECTRA INC. MILWAUKEE WI DOT‐12 DONG SHIN SAFETY GLASS CO., LTD. BOOKILMEON, JEONNAM KOREA DOT‐13 YAU BONG CAR GLASS CO., LTD. ON LOK CHUEN, NEW TERRITORIES HONG KONG DOT‐15 LIBBEY‐OWENS‐FORD CO TOLEDO, OH, USA DOT‐16 HAYES‐ALBION CORPORATION JACKSON, MS, USA DOT‐17 TRIPLEX SAFETY GLASS COMPANY LIMITED BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND DOT‐18 PPG INDUSTRIES PITTSBURGH, PA, USA DOT‐19 PPG CANADA INC.,DUPLATE DIVISION OSHAWA,ONTARIO, CANADA DOT‐20 ASAHI GLASS CO LTD TOKYO, JAPAN DOT‐21 CHRYSLER CORP DETROIT, MI, USA DOT‐22 GUARDIAN INDUSTRIES CORP AUBURN HILLS, MI, USA DOT‐23 NIPPON SHEET GLASS CO. LTD OSAKA, JAPAN DOT‐24 SPLINTEX BELGE S.A. GILLY, BELGIUM DOT‐25 FLACHGLAS AUTOMOTIVE GmbH WITTEN, GERMANY Page 1 of 27 Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐26 CORNING GLASS WORKS CORNING, NY, USA DOT‐27 SEKURIT SAINT‐GOBAIN DEUTSCHLAND GMBH GERMANY DOT‐32 GLACERIES REUNIES S.A. BELGIUM DOT‐33 LAMINATED GLASS CORPORATION DETROIT, MI, USA DOT‐35 PREMIER AUTOGLASS CORPORATION LANCASTER, OH, USA DOT‐36 SOCIETA ITALIANA VETRO S.P.A. -

BETH BARRETT STAN SHIELDS Artistic Director Programming Manager

BETH BARRETT STAN SHIELDS Artistic Director Programming Manager DEAR MEMBERS OF THE PRESS: It is our distinct honor to welcome you to the 45th annual Seattle International Film Festival! We are so happy to have you join this year as a partner at the Festival. It’s your work that helps connect filmmakers and audiences through the powerful experience of film. We are deeply appreciative of the knowledge, skill, and passion you bring to your work that has allowed us to become the SIFF we are today. Our 2019 Media Guide filled with all the pertinent information you’ll need to navigate the next 25 days: media guidelines and contacts, film listings, forums, and events. Many of you are already familiar with SIFF’s extensive Festival offerings. For those of you who are attending for the first time, we are here to help you discover the depth and range of our programming. The greater press community has always been an integral part of SIFF and we look forward to sharing with you all that our festival has to offer. Sincerely, Beth Barrett Stan Shields SIFF.NET · 206.464.5830 · PRESS OFFICE 206.315.0694 · [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 . PRESS INFORMATION 5 . SIFF STAFF 11 . SIFF BOARD 12 . ABOUT SIFF 13 . SIFF 2019 BY THE NUMBERS 14 . SIFF 2019 FACT SHEET 15 . EVENT SCHEDULE 22 . MEDIA GUIDELINES 23 . HOLD REVIEWS 27 . VENUES 28 . TICKETING 31 . FEATURE FILM INFORMATION 39 . FEATURES BY COUNTRY 44 . TOPICS OF INTEREST 56 . AWARDS & COMPETITIONS 64 . LOUNGE 65 . EDUCATION 66 . SPECIAL GUESTS 67 . -

California State University, Northridge Exploitation

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE EXPLOITATION, WOMEN AND WARHOL A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art by Kathleen Frances Burke May 1986 The Thesis of Kathleen Frances Burke is approved: Louise Leyis, M.A. Dianne E. Irwin, Ph.D. r<Iary/ Kenan Ph.D. , Chair California State. University, Northridge ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Dr. Mary Kenon Breazeale, whose tireless efforts have brought it to fruition. She taught me to "see" and interpret art history in a different way, as a feminist, proving that women's perspectives need not always agree with more traditional views. In addition, I've learned that personal politics does not have to be sacrificed, or compartmentalized in my life, but that it can be joined with a professional career and scholarly discipline. My time as a graduate student with Dr. Breazeale has had a profound effect on my personal life and career, and will continue to do so whatever paths my life travels. For this I will always be grateful. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In addition, I would like to acknowledge the other members of my committee: Louise Lewis and Dr. Dianne Irwin. They provided extensive editorial comments which helped me to express my ideas more clearly and succinctly. I would like to thank the six branches of the Glendale iii Public Library and their staffs, in particular: Virginia Barbieri, Claire Crandall, Fleur Osmanson, Nora Goldsmith, Cynthia Carr and Joseph Fuchs. They provided me with materials and research assistance for this project. I would also like to thank the members of my family. -

GLASTON CORPORATION Yliopistonkatu 7 - 00100 Helsinki - Finland Tel.: +358 10 500 500 / Fax: +358 10 500 6515

2015 world directory 2 - Copia omaggio € ââÊ`ÊV«iÀÌ>Ê > Suppliers’ THAT’S WHY THIS WILL BE Profiles YOUR NEXT LAMINATING LINE ZERO DEFECTS ZERO WASTE ZERO DOWNTIME > Suppliers’ ZERO DISPERSION Products & ÊÊ°ÊÓÇÉäÓÉÓää{ÊcÊ{È®Ê>ÀÌ°Ê£]ÊV>Ê£ÊÊ Ê>ÊÊÊUÊÊÊ*Ài Yellow Pages > Glassworks’ Addresses ÌÌ]Ê*ÃÌiÊÌ>>iÊ-«>ÊÊ-«i`°ÊÊ>°Ê«°ÊÊ °°ÊÎxÎÉÓääÎÊVÛ° Powerlam FLAT GLASS LAMINATING LINE WITH EVA & PVB AVAILABLE IN ABSOLUTE PERFORMANCE AND RELIABILITY INTERACTIVE VERSIONS TOO }ÞÊÌiÀ>Ì>]Ê->ÀÌiiÀ}ÞÊ-°À°°]Ê À°Ê,ië°Ê>ÀVÊ*i DESKTOP DISCOVER MORE www.rcnengineering.it IPAD/IPHONE RCN ENGINEERING S.R.L. Via Marcatutto, 7 - 20080 Albairate (MI) Italy Tel +39 02 94602434 - [email protected] www.rcnengineering.it -Õ««iiÌÊÊ>Ê°Ê£{{ÊÊ>ÀV É«ÀÊÊ°ÊÓÉÓä£xÊ`Ê>ÃÃ/iV ANDROID DEVICES www.glassonline.com Multi-roller coating machine for the enamelling and design printing of float glass sheets. ROLLMAC a division of GEMATA - Via Postale Vecchia, 77 - 36070 Trissino (VI) Italy Tel. +39.0445.490618 - Fax +39.0445.490639 - E-mail: [email protected] - www.rollmac.it Because we care Revolutionary. Also our technologies. INSULATING GLASS MANUFACTURING Bystronic glass symbolises innovation with machinery, HANDLING EQUIPMENT systems and services for the processing of architectural AUTOMOTIVE GLASS PREPROCESSING and automotive glass focused on tomorrow’s market. From basic requirements through to entire, customised installations Bystronic glass provides pioneering solutions – naturally, all in the highest quality. www.bystronic-glass.com IR medium wave twin tubes emitters for: iÃÊÌ>µÕ>ÀÌâÊ>ÃÊ«À`ÕViÃÊ } ÞÊ Ê UÊ >>Ì}Êià >««ÀiV>Ìi`Ê iµÕ«iÌÊ vÀÊ Ì iÊ }>ÃÃÊ Ê UÊ ÀÀÀ}Êià industry such as manual and au- Ê UÊ `ÀÞÊÃVÀiiÊ«ÀÌ}Êià tomatic tin side detectors and UV polymerization units.