The Exchange at Halesi: a Sacred Place and a Societal Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

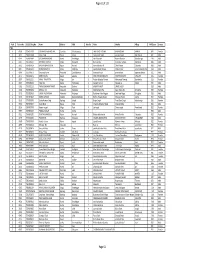

Club Health Assessment MBR0087

Club Health Assessment for District 325A1 through April 2021 Status Membership Reports Finance LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Activity Account Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Report *** Balance Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater report in 3 more than of officers thatin 12 months within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not haveappears in two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active red Clubs less than two years old SC 138770 Bansbari 07/12/2019 Active 41 15 0 15 57.69% 26 0 N 1 $600.02 P,MC 138952 Bargachhi Green City 07/12/2019 Active 25 1 0 1 4.17% 24 4 N 5 142398 Biratnagar A One 08/09/2020 Active 32 32 0 32 100.00% 0 2 N 1 M,MC,SC 138747 Biratnagar Birat Medical 07/12/2019 Active 21 1 0 1 5.00% 20 3 N 3 90+ Days P,S,T,M,VP 138954 Biratnagar Capital City 07/12/2019 Active 20 0 0 0 0.00% 20 21 1 None N/R 90+ Days MC,SC M,MC,SC 140415 Biratnagar Entrepreneur 01/06/2020 Active 18 0 0 0 0.00% 20 10 2 R 10 90+ Days M 139007 Biratnagar Greater 07/12/2019 Active 31 8 3 5 19.23% 26 1 4 3 N 3 Exc Award (06/30/2020) VP 139016 Biratnagar Health Professional 07/12/2019 Active 26 4 1 3 13.04% 23 1 0 N 3 Exc Award (06/30/2020) 138394 Biratnagar Mahanagar -

Functions of Nachhung (Shaman) in the Chamling Rai in Eastern Nepal

Patan Pragya (Volume: 7 Number: 1 2020) [ ISSN No. 2595-3278 Received Date: July 2020 Revised: Oct. 2020 Accepted: Dec.2020 https://doi.org/10.3126/pragya.v7i1.35247 Functions of Nachhung (Shaman) in the Chamling Rai in Eastern Nepal Rai Puspa Raj Abstract Rai is an indigenous people and decedent of Kirati dynasty, inhabitant of eastern part of Nepal. It is known as Kirat Pradesh before the unification of Nepal. Now, Kirat Pradesh is became political word in Nepal for name of province number 1 but not endorse till present. The Chamling Rai society is comprised different interdependent parts and units as like religion, culture, economy, polity, educational etc. Kirat religion is a part of Rai community constituted by the different units and interdepended among different parts. The Chamling word Nachhung (shaman) is called priest of the Kirat religion. So, this article focuses on the Nachhung who is the Rai priest, shaman and healer as functional unit of the Rai society. The main research questions if how the Nachhung plays function as the being part of Rai society and contribute to existence of Rai society as whole. It explores the interdependence of Nachhung on other parts like rite and ritual, marriage, feast and festival, community, health, social and religious activities. Keywords: Nachhung's function, rite and ritual, Sakela festival, healing illness. Introduction Shamanism is a kind of religion in the primitive society. Tylor argues that animism is the first religion of the world. There was found debate on shamanism among different scholars in 19th centuray. Tylor, Schmidt considered shamanism as primitive religion but Durkhiem, Marcel Mauss considered magic as immoral and private act. -

Social and Gender Analysis in Natural Resource Management

Social and Gender Analysis in Natural Resource Management Learning Studies and Lessons from Asia Edited by RONNIE VERNOOY Copyright © International Development Research Centre, Canada, 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The boundaries and names shown on the maps in this publication do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the International Development Research Centre. Jointly published in 2006 by Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd B-42, Panchsheel Enclave New Delhi 110 017 www.indiasage.com Sage Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320 Sage Publications Ltd 1 Oliver's Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP and International Development Research Centre PO Box 8500, Ottawa, ON, Canada K1G 3H9, [email protected] / www.idrc.ca China Agriculture Press 18 Maizidian Street, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100026, China, www.ccap.org.cn Published by Tejeshwar Singh for Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd, phototypeset in 10.5/12.5 pt Minion by Star Compugraphics Private Limited, Delhi and printed at Chaman Enterprises, New Delhi. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Social and gender analysis in natural resource management: learning studies and lessons from Asia/edited by Ronnie Vernooy. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Rural development—Asia—Case studies. 2. Women in development— Asia—Case studies. 3. Natural resources—Management—Research. I. Vernooy, Ronnie, 1963– HC412.5.S63 333.708'095—dc22 2006 2005033467 ISBN: 0–7619–3462–6 (Hb) 81–7829–612–8 (India-Hb) 0–7619–3463–4 (Pb) 81–7829–613–6 (India-Pb) 1-55250-218-X (IDRC e-book) Sage Production Team: Payal Dhar, Ashok R. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

Politics of R Esistance

Politics of Resistance Politics Tis book illustrates an exciting approach to understanding both Indigenous Peoples of Nepal are searching for the state momentous and everyday events in the history of South Asia. It which recognizes and refects their identities. Exclusion of advances notions of rupture and repair to comprehend the afermath indigenous peoples in the ruling apparatus and from resources of natural, social and personal disasters, and demonstrates the of the “modern states,” and absence of their representation and generality of the approach by seeking their historical resolution. belongingness to its structures and processes have been sources Te introduction of rice milling technology in a rural landscape of conficts. Indigenous peoples are engaged in resistance in Bengal,movements the post-cold as the warstate global has been shi factive in international in destroying, relations, instead of the assassinationbuilding, their attempt political, on a economicjournalist and in acultural rented institutions.city house inThe Kathmandu,new constitution the alternate of 2015and simultaneousfailed to address existence the issues, of violencehence the in non-violentongoing movements,struggle for political,a fash feconomic,ood caused and by cultural torrential rights rains and in the plainsdemocratization of Nepal, theof the closure country. of a China-India border afer the army invasionIf the in Tibet,country and belongs the appearance to all, if the of outsiderspeople have in andemocratic ethnic Taru hinterlandvalues, the – indigenous scholars in peoples’ this volume agenda have would analysed become the a origins, common anatomiesagenda and ofdevelopment all. If the state of these is democratic events as andruptures inclusive, and itraised would interestingaddress questions the issue regarding of justice theirto all. -

Himalayan Journal of Education and Literature Open Access

Himalayan Journal of Education and Literature Open Access Research Article Identity Making among Migrant Rai in Lubhu, Lalitpur Area in Kathmandu Valley Puspa Raj Rai Patan Multiple Campus, Lalitpur, Bagmati Pradesh, Nepal *Corresponding Author Abstract: Puspa Raj Rai Article History Received: 25.12.2020 Accepted: 09.01.2021 Published: 15.01.2021 Citations: Puspa Raj Rai (2021); Identity Making among Migrant Rai in Lubhu, Lalitpur Area in Kathmandu Valley.Hmlyan Jr Edu Lte, 2(1) 1- 7. Copyright @ 2021: This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium for non commercial use (NonCommercial, or CC-BY- Keywords: NC) provided the original author and source are credited. INTRODUCTION Ethnic identity is the product of a social process whereby social relationships are maintaining, modified. It is the process of identification of communal level and individual level. Identity is formed by social processes and social relationships are the key factor for maintaining, modifying, and reshaping the identity. Members can identify themselves as different from another social group. Barth (1996) argues that ethnic identity constructs some agreement from by outsiders and insider group members as well as identify contextually by themselves from outsider and insider group members. Ethnic identity became the most popular term for a decade in Nepal. Politicians and social scientists have pronounced this term in the state restructuring process of Nepal. Some academic works on ethnic identity have also been done like Shneiderman (2009), Fisher (2001), Gunaratne (2002), Gubhaju (1999) in Nepal but insufficient in terms of migrant Rai ethnic identity. -

Deixis System in Bantawa Rai and English Language A

DEIXIS SYSTEM IN BANTAWA RAI AND ENGLISH LANGUAGE RAI RAI 2016 A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Education 2126 SITAL In Partial Fulfillment for the Masters of Education in English LANGUAGE Submitted by Sital Rai TAWA RAI AND ENGLISH Faculty of Education Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal DEIXIS SYSTEM INDEIXIS BAN 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that to the best of my knowledge this thesis is original; no part of it was earlier submitted for the candidature of research degree to any University. Date: 24/09/2016 ________________ Sital Rai 2 RECOMMENDATION FOR ACCEPTANCE This is to certify that Ms. Sital Rai has completed the research work of her M. Ed. Thesis entitled “Deixis System in Bantawa Rai and English Language” under my guidance and supervision. I recommend the thesis for acceptance. Date: 25/09/2016 ____________________ Dr. Anjana Bhattarai (Supervisor) Professor and Head Department of English Education University Campus T. U., Kirtipur 3 RECOMMENDATION FOR EVALUATION This thesis has been recommended for evaluation by the following Research Guidance Committee. Signature Dr. Anjana Bhattarai (Supervisor) ______________ Professor and Head Chairperson Department of English Education University Campus, T. U., Kirtipur Dr. Govinda Raj Bhattarai ____________ Member Professor, Department of English education University Campus, T. U. Kirtipur Dr. Purna Bahadur Kadel ______________ Lecture, Member Department of English Education University Campus, T. U. Kirtipur Date: 03/08/2015 4 EVALUATION AND APPROVAL This thesis has been evaluated and approved by the following Thesis Evaluation Committee. Signature Dr.Anjana Bhattarai (Supervisor) ______________ Professor and Head Chairperson Department of English Education University Campus, T. -

ROJ BAHADUR KC DHAPASI 2 Kamalapokhari Branch ABS EN

S. No. Branch Account Name Address 1 Kamalapokhari Branch MANAHARI K.C/ ROJ BAHADUR K.C DHAPASI 2 Kamalapokhari Branch A.B.S. ENTERPRISES MALIGAON 3 Kamalapokhari Branch A.M.TULADHAR AND SONS P. LTD. GYANESHWAR 4 Kamalapokhari Branch AAA INTERNATIONAL SUNDHARA TAHAGALLI 5 Kamalapokhari Branch AABHASH RAI/ KRISHNA MAYA RAI RAUT TOLE 6 Kamalapokhari Branch AASH BAHADUR GURUNG BAGESHWORI 7 Kamalapokhari Branch ABC PLACEMENTS (P) LTD DHAPASI 8 Kamalapokhari Branch ABHIBRIDDHI INVESTMENT PVT LTD NAXAL 9 Kamalapokhari Branch ABIN SINGH SUWAL/AJAY SINGH SUWAL LAMPATI 10 Kamalapokhari Branch ABINASH BOHARA DEVKOTA CHOWK 11 Kamalapokhari Branch ABINASH UPRETI GOTHATAR 12 Kamalapokhari Branch ABISHEK NEUPANE NANGIN 13 Kamalapokhari Branch ABISHEK SHRESTHA/ BISHNU SHRESTHA BALKHU 14 Kamalapokhari Branch ACHUT RAM KC CHABAHILL 15 Kamalapokhari Branch ACTION FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION TRUST GAHANA POKHARI 16 Kamalapokhari Branch ACTIV NEW ROAD 17 Kamalapokhari Branch ACTIVE SOFTWARE PVT.LTD. MAHARAJGUNJ 18 Kamalapokhari Branch ADHIRAJ RAI CHISAPANI, KHOTANG 19 Kamalapokhari Branch ADITYA KUMAR KHANAL/RAMESH PANDEY CHABAHIL 20 Kamalapokhari Branch AFJAL GARMENT NAYABAZAR 21 Kamalapokhari Branch AGNI YATAYAT PVT.LTD KALANKI 22 Kamalapokhari Branch AIR NEPAL INTERNATIONAL P. LTD. HATTISAR, KAMALPOKHARI 23 Kamalapokhari Branch AIR SHANGRI-LA LTD. Thamel 24 Kamalapokhari Branch AITA SARKI TERSE, GHYALCHOKA 25 Kamalapokhari Branch AJAY KUMAR GUPTA HOSPITAL ROAD 26 Kamalapokhari Branch AJAYA MAHARJAN/SHIVA RAM MAHARJAN JHOLE TOLE 27 Kamalapokhari Branch AKAL BAHADUR THING HANDIKHOLA 28 Kamalapokhari Branch AKASH YOGI/BIKASH NATH YOGI SARASWATI MARG 29 Kamalapokhari Branch ALISHA SHRESTHA GOPIKRISHNA NAGAR, CHABAHIL 30 Kamalapokhari Branch ALL NEPAL NATIONAL FREE STUDENT'S UNION CENTRAL OFFICE 31 Kamalapokhari Branch ALLIED BUSINESS CENTRE RUDRESHWAR MARGA 32 Kamalapokhari Branch ALLIED INVESTMENT COMPANY PVT. -

Tinjure-Milke-Jaljale Rhododendron Conservation Area a Strategy

Tinjure-Milke-Jaljale Rhododendron Conservation Area A Strategy for Sustainable Development PreparedPrepared in partnershippartnership with IUCN NepalNepal NORM 2010 IUCN Nepal P.O. Box 3923 Kathmandu, Nepal Email: [email protected] URL: www.iucnnepal.org Copy right: © 2010 IUCN Nepal Published by: IUCN Nepal Country Office The role of Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) in supporting IUCN Nepal is gratefully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is permitted without prior written consent from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other non-commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. ISBN: 978-9937-8222-3-7 Available from: IUCN Nepal, P.O. Box 3923, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: (977-1) 5528781, 5528761, Fax: (977-1) 5536786 email: [email protected], URL: http://iucnnepal.org Sponsors Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) The initial draft report was prepared by a team of experts headed by Prof. Dr. Khadga Basnet with support from Mr. Laxman Tiwari (NORM), Mr. Rajendra Khanal, Mr. Meen Dahal, Dr. V.N. Jha and Miss. Utsala Shrestha (IUCN Dharan Office) and Mr. Mingma Norbu Sherpa IUCN Country Office. Table of contents Index of Tables Index of Figures List of Abbreviations/Acronyms Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Fact Sheet....................................................................................................................................... -

Dharan-Booklet-Spread-1.Pdf

dharan YOUR NEXT DESTINATION DHARAN SUB-METROPOLITAN CITY DHARAN TOURISM DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE DharanYOUR NEXT DESTINATION DHARAN SUB-METROPOLITAN CITY DHARAN TOURISM DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE message from messages message from YOUR NEXT DESTINATION the deputy the chairman Dharan the acting mayor cordinator (ETM-2019) Published by Dharan Sub-Metropolitan City Promoted by Dharan is multi-lingual and multi-cultural city of East Nepal. Ancient temples Nepal has a popular saying that says ‘guests are like gods’. This saying shows Dharan, the Gateway of Eastern Nepal and the adjoining region has always Dharan Tourism Development Committee and historic heritages have made Dharan a proud and prosperous city of Nepal. that we Nepalese have culture and tradition to be hospitable to all guests. been one of the best tourism destinations of this state due to its rich cultural and Supported by The serene surrounding and its beautiful places have also made Dharan a religious heritage, adventure activities and educational and medical hub legacy. East Tourism Mart Organizing Committee perfect place for travel and tourism. Because of availabilities of infrastructures for Dharan, beautiful city situated in the eastern part of Nepal, is rice for its cultural, It’s my sincere and humble request that through active promotional activities in Photograph by Eco-tourism, agro-tourism, adventure tourism, sports tourism, Dharan is being religious, geographical and natural diversities. Various virgin touristic potential the International market as well as the domestic market we must attract maximum Rajesh Shakya (Tony), developed as touristic hub. places of Dharan are waiting publicity and protection. Dharan is also significant tourist to Dharan and adjoining regions. -

Club Health Assessment MBR0087

Club Health Assessment for District 325A1 through July 2018 Status Membership Reports Finance LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Activity Account Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Report *** Balance Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no report When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater in 3 more than of officers that in 12 within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not have months two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active appears in in brackets in red in red red red indicated Email red Clubs less than two years old 129490 Anarmani 01/06/2017 Active 27 0 0 0 0.00% 27 19 3 T N/R 131959 Bhedetar 07/05/2017 Active 20 0 0 0 0.00% 20 0 2 N/R 133509 Biratnagar Academic 12/28/2017 Active 22 0 0 0 0.00% 0 7 2 P,VP,MC N/R 128478 Biratnagar Bargachhi 09/23/2016 Active 18 0 7 -7 -28.00% 25 2 0 M,MC N/R 129487 Biratnagar Fusion 02/27/2017 Active 24 0 0 0 0.00% 24 2 S,VP,SC 2 131965 Biratnagar Global 07/05/2017 Active 28 0 0 0 0.00% 20 0 2 T,M 0 131973 Biratnagar Gograha 08/25/2017 Active 22 0 0 0 0.00% 0 2 SC N/R 133181 Biratnagar Laligunrash 12/18/2017 Active 20 0 0 0 0.00% 0 1 2 T,M,VP,MC,SC N/R 131960 Biratnagar Mid City 07/05/2017 Active 25 0 0 0 0.00% 24 3 2 VP,SC 4 132533 Biratnagar Mills Area 09/12/2017