UC Santa Barbara Himalayan Linguistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal: SASEC Road Connectivity Project: Leguwaghat-Bhojpur

Initial Environmental Examination February 2013 NEP: SASEC Road Connectivity Project Leguwaghat — Bhojpur Subproject Prepared by the Department of Road, Ministry of Physical Planning, Works and Transport Management for the Asian Development Bank. 16. ii CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 21 February 2013) Currency unit – Nepalese rupee (NR) NR1.00 – $ 0.0115340254 $1.00 – NR86.700000 ABBREVIATIONS EPR Environmental Protection Rules ES Environmental Specialist EWH East-West Highway FIDIC Federation International Des Ingenieurs- Conseils FS Feasibility Study GESU Geo-Environmental and Social Unit GHG Green House Gas IA Implementing Agency ICIMOD International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development IEE Initial Environmental Examination IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature JICA Japan International Co-operative Agency LPG Liquefied Petroleum Gas MCT Main Central Trust MHH Mid-Hill Highway MOE Ministry of Environment MoPPW Ministry of Physical Planning and Works MRM Mahendra Raj Marg NAAQS Nepal Ambient Air Quality Standard NEP Nepal NGO Non Government Organization NOx Nitrogen Oxide OD Origin-Destination PD Project Directorate pH Percentage of Hydrogen PPE Personal Protective Equipment PIP Priority Investment Plan PPMO Public Procurement Monitoring Office RCP Road Connectivity Project - ADB RAP Rural Access Programmme -DFID RAP Rural Access Program RCC Reinforced Cement Concrete RCSP Road Connectivity Sector Project - ADB iii REA Rapid Environmental Assessment RIP Road Improvement Project- DOR RNDP Road Network Development Project -

A Study on Factors of Student Learning Achievements and Dynamics for Better Learning Conditions: a Case Study Focused to Grade Five in Some Selected Schools

A Study on Factors of Student Learning Achievements and Dynamics for Better Learning Conditions: A case study focused to grade five in some selected schools Submitted to Department of Education, Ministry of Education Presented by Rural Development Society, Chabahil &Molung Foundation, Koteshwor, Kathmandu 2074 Research Team Rishi Ram Rijal, Ph. D., Team Leader Netra Prasad Paudel, Ph. D., Senior Researcher Santosh Gautam, Data Analyst Shyam Krishna Bista, Researcher Drona Dahal, Researcher Tirtha Raj Khatiwada, Researcher Karna Bahadur Chongbang, Researcher English Mahasaraswati S. School (High) Banedhungra L.S. School(Low) Nepali Sarada H.S. School (High) Sarada L.S.School (Low) Nepali Samaijee S. School (High) Siddhartha L. S. School (Low) English Kalika H.S. School (High) Maths Bhanudaya S.School (Low) Saraswati L.S. School (High) Nepal Rastriya S. School,(Low) Maths Nepaltar S. School(Low) Diyalo L.S. School(High) 3 Acknowledgements This case study report has been prepared to fulfill the requirements of research project of 2017 approved by the Department of Education under the Ministry of Education. Without the contribution made by several including Director General of DOE, under secretaries, other personnel of DOE, DEOs, SSs, RPs, head teachers, teachers, chairpersons of SMCs and PTAs of the sample schools along with the staff of consultancy office, it would not have been possible to accomplish this outcome. So, we would like to acknowledge them all here. First of all, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to the authority concerned for providing the opportunity to undertake this research to Rural Development Society, Chabahil, Kathmandu and Molung Foundation, Koteshwor, Kathmandu. -

Agricultural Transformation Around Koshi Hill Region: a Rural Development Perspective

95 NJ: NUTA Agricultural Transformation around Koshi Hill Region: A Rural Development Perspective Tirtha Raj Timalsina Lecturer, Dhankuta Multiple Campus, Dhankuta Eastern Nepal Email for correspondence:[email protected] Abstract Agriculture is considered to be the basic segment and the backbone of developing economy. In the same way it is a prime and domonent sector of Nepalese rural livelihood. By considering this fact, the true value of rural development lies on the rapid transformation of existing agricultural sector. The aim of this study is to analyze the role of agricultural transformation for rural development of Koshi Hill Region (KHR) of eastern Nepal. Both the primary as well as secondary data and information have been used to obtain the required findings. The study reveals the fact that agriculture is inevitable for rural people and its transformation is essential for the development of rural areas and the nation as a whole. Including primarily to the road network, the development of infrastructure can play the detrimental role to change the backward and rural scenario of this country. Key words: Agricultural transformation, rural development, Koshi-Hill, essential, backbone, access. Conceptualization Agriculture is an important segment of traditional (feudal) economy, the transformation from feudalism to capitalism necessarily implies a transformation of agriculture (Lekhi, 2005). Thereby, agriculture is the prime occupation and also the backbone of most of the developing economies. The countries that are in the low profile of international comparision, no doubt they are moving on stagnat and backward agriculture with under or misutilized physical as well as human resources. The country which are backward and underdeveloped are not always facing the scarcity of resources but the techniques or to know how to manage the scarcely available means and reslurces is accepted as the principal understanding of development science. -

Functions of Nachhung (Shaman) in the Chamling Rai in Eastern Nepal

Patan Pragya (Volume: 7 Number: 1 2020) [ ISSN No. 2595-3278 Received Date: July 2020 Revised: Oct. 2020 Accepted: Dec.2020 https://doi.org/10.3126/pragya.v7i1.35247 Functions of Nachhung (Shaman) in the Chamling Rai in Eastern Nepal Rai Puspa Raj Abstract Rai is an indigenous people and decedent of Kirati dynasty, inhabitant of eastern part of Nepal. It is known as Kirat Pradesh before the unification of Nepal. Now, Kirat Pradesh is became political word in Nepal for name of province number 1 but not endorse till present. The Chamling Rai society is comprised different interdependent parts and units as like religion, culture, economy, polity, educational etc. Kirat religion is a part of Rai community constituted by the different units and interdepended among different parts. The Chamling word Nachhung (shaman) is called priest of the Kirat religion. So, this article focuses on the Nachhung who is the Rai priest, shaman and healer as functional unit of the Rai society. The main research questions if how the Nachhung plays function as the being part of Rai society and contribute to existence of Rai society as whole. It explores the interdependence of Nachhung on other parts like rite and ritual, marriage, feast and festival, community, health, social and religious activities. Keywords: Nachhung's function, rite and ritual, Sakela festival, healing illness. Introduction Shamanism is a kind of religion in the primitive society. Tylor argues that animism is the first religion of the world. There was found debate on shamanism among different scholars in 19th centuray. Tylor, Schmidt considered shamanism as primitive religion but Durkhiem, Marcel Mauss considered magic as immoral and private act. -

Existing Environmental Conditions

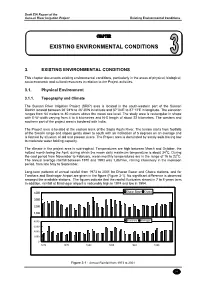

Draft EIA Report of the Sunsari River Irrigation Project Existing Environmental Conditions CHAPTER EXISTING ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS 3. EXISTING ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS This chapter documents existing environmental conditions, particularly in the areas of physical, biological, socio-economic and cultural resources in relation to the Project activities. 3.1. Physical Environment 3.1.1. Topography and Climate The Sunsari River Irrigation Project (SRIP) area is located in the south-western part of the Sunsari District located between 26°24′N to 26°30′N in latitude and 87°04′E to 87°12′E in longitude. The elevation ranges from 64 meters to 80 meters above the mean sea level. The study area is rectangular in shape with E-W width varying from 4 to 8 kilometres and N-S length of about 22 kilometres. The western and southern part of the project area is bordered with India. The Project area is located at the eastern bank of the Sapta Koshi River. The terrain starts from foothills of the Siwalik range and slopes gently down to south with an inclination of 5 degrees on an average and is formed by alluvium of old and present rivers. The Project area is dominated by sandy soils having low to moderate water holding capacity. The climate in the project area is sub-tropical. Temperatures are high between March and October, the hottest month being the April, during which the mean daily maximum temperature is about 340C. During the cool period from November to February, mean monthly temperatures are in the range of 16 to 220C. The annual average rainfall between 1970 and 1993 was 1,867mm, raining intensively in the monsoon period, from late May to September. -

Nepal: the Maoists’ Conflict and Impact on the Rights of the Child

Asian Centre for Human Rights C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi-110058, India Phone/Fax: +91-11-25620583; 25503624; Website: www.achrweb.org; Email: [email protected] Embargoed for: 20 May 2005 Nepal: The Maoists’ conflict and impact on the rights of the child An alternate report to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child on Nepal’s 2nd periodic report (CRC/CRC/C/65/Add.30) Geneva, Switzerland Nepal: The Maoists’ conflict and impact on the rights of the child 2 Contents I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 4 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS .................. 5 III. GENERAL PRINCIPLES .............................................................................. 15 ARTICLE 2: NON-DISCRIMINATION ......................................................................... 15 ARTICLE 6: THE RIGHT TO LIFE, SURVIVAL AND DEVELOPMENT .......................... 17 IV. CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS............................................................ 17 ARTICLE 7: NAME AND NATIONALITY ..................................................................... 17 Case 1: The denial of the right to citizenship to the Badi children. ......................... 18 Case 2: The denial of the right to nationality to Sikh people ................................... 18 Case 3: Deprivation of citizenship to Madhesi community ...................................... 18 Case 4: Deprivation of citizenship right to Raju Pariyar........................................ -

FINAL REPORT.Pdf

Government of Nepal Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Ilam Municipality Ilam Preparation of GIS based Digital Base Urban Map Upgrade of Ilam Municipality, Ilam Final Report Submitted By: JV Grid Consultant Pvt. Ltd, Galaxy Pvt. Ltd and ECN Consultancy Pvt. Ltd June 2017 Government of Nepal Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Ilam Municipality Ilam Preparation of GIS based Digital Base Urban Map Upgrade of Ilam Municipality, Ilam Final Report MUNICIPALITY PROFILE Submitted By: JV Grid Consultant Pvt. Ltd, Galaxy Pvt. Ltd and ECN Consultancy Pvt. Ltd June 2017 Table of Content Contents Page No. CHAPTER - I ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 NAMING AND ORIGIN............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 LOCATION.............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 SETTLEMENTS AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS ......................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER - II.................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 PHYSIOGRAPHY......................................................................................................................................4 2.2 GEOLOGY/GEOMORPHOLOGY -

Benefit Sharing and Sustainable Hydropower: Lessons from Nepal

ICIMOD Research Report 2016/2 Benefit Sharing and Sustainable Hydropower: Lessons from Nepal 1 About ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, ICIMOD, is a regional knowledge development and learning centre serving the eight regional member countries of the Hindu Kush Himalayas – Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – and based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Globalization and climate change have an increasing influence on the stability of fragile mountain ecosystems and the livelihoods of mountain people. ICIMOD aims to assist mountain people to understand these changes, adapt to them, and make the most of new opportunities, while addressing upstream-downstream issues. We support regional transboundary programmes through partnership with regional partner institutions, facilitate the exchange of experience, and serve as a regional knowledge hub. We strengthen networking among regional and global centres of excellence. Overall, we are working to develop an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem to improve the living standards of mountain populations and to sustain vital ecosystem services for the billions of people living downstream – now, and for the future. About Niti Foundation Niti Foundation is a non-profit public policy institute committed to strengthening and democratizing the policy process of Nepal. Since its establishment in 2010, Niti Foundation’s work has been guided by its diagnostic study of Nepal’s policy process, which identifies weak citizen participation, ineffective policy implementation, and lack of accountability as the three key factors behind the failure of public policies in the country. In order to address these deficiencies, Niti Foundation works towards identifying policy concerns by encouraging informed dialogues and facilitating public forums that are inclusive of the citizens, policy experts, think tanks, interest groups, and the government. -

Social and Gender Analysis in Natural Resource Management

Social and Gender Analysis in Natural Resource Management Learning Studies and Lessons from Asia Edited by RONNIE VERNOOY Copyright © International Development Research Centre, Canada, 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The boundaries and names shown on the maps in this publication do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the International Development Research Centre. Jointly published in 2006 by Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd B-42, Panchsheel Enclave New Delhi 110 017 www.indiasage.com Sage Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320 Sage Publications Ltd 1 Oliver's Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP and International Development Research Centre PO Box 8500, Ottawa, ON, Canada K1G 3H9, [email protected] / www.idrc.ca China Agriculture Press 18 Maizidian Street, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100026, China, www.ccap.org.cn Published by Tejeshwar Singh for Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd, phototypeset in 10.5/12.5 pt Minion by Star Compugraphics Private Limited, Delhi and printed at Chaman Enterprises, New Delhi. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Social and gender analysis in natural resource management: learning studies and lessons from Asia/edited by Ronnie Vernooy. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Rural development—Asia—Case studies. 2. Women in development— Asia—Case studies. 3. Natural resources—Management—Research. I. Vernooy, Ronnie, 1963– HC412.5.S63 333.708'095—dc22 2006 2005033467 ISBN: 0–7619–3462–6 (Hb) 81–7829–612–8 (India-Hb) 0–7619–3463–4 (Pb) 81–7829–613–6 (India-Pb) 1-55250-218-X (IDRC e-book) Sage Production Team: Payal Dhar, Ashok R. -

Leaving No One Behind in the Health Sector an SDG Stocktake in Kenya and Nepal

Report Leaving no one behind in the health sector An SDG stocktake in Kenya and Nepal December 2016 Overseas Development Institute 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ Tel. +44 (0) 20 7922 0300 Fax. +44 (0) 20 7922 0399 E-mail: [email protected] www.odi.org www.odi.org/facebook www.odi.org/twitter Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from ODI Reports for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holder, ODI requests due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI website. The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of ODI. © Overseas Development Institute 2016. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial Licence (CC BY-NC 4.0). Cover photo: A mother brings her child to be vaccinated for TB during routine vaccinations at a district public health office, immunisation clinic, Pokhara, Nepal. © Jim Holmes for AusAID. Acknowledgements This report has been contributed to and written by an international and multidisciplinary team of researchers comprising: Tanvi Bhatkal, Catherine Blampied, Soumya Chattopadhyay, Maria Ana Jalles D’Orey, Romilly Greenhill, Tom Hart, Tim Kelsall, Cathal Long, Shakira Mustapha, Moizza Binat Sarwar, Elizabeth Stuart, Olivia Tulloch and Joseph Wales (Overseas Development Institute), Alasdair Fraser and Abraham Rugo Muriu (independent researchers in Kenya), Shiva Raj Adhikari and Archana Amatya (Tibhuvan University, Nepal) and Arjun Thapa (Pokhara University, Nepal). We are most grateful to all the interview participants we learnt from during the course of the work and to the following individuals for their support and facilitation of the research process: Sarah Parker at ODI. -

Socio-Economic Background of the Women Workers in Guranse Tea Estate, Dhankuta

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/tgb.v6i0.26170 Socio-economic Background of the Women Workers in Guranse Tea Estate, Dhankuta Anita Thapa1 Abstract Abundance of female workers in tea estate is common phenomena in the context of Nepalese tea industry. Women are main work force especially for leaf picking in any tea industry. So, the role of women participation is notable in this sector. This study focusses on socio- economic background of women workers in Guranse Tea Estate, Dhankuta. Both qualitative and quantitative methods have been used to collect data and information through questionnaire, interview, focused group discussion, key informant interview and observation. Various types and nature of tea workers are found in the tea industry. Different types of socio-economic background such as caste/ethnicity, age group, educational status, land ownership, income level etc. have been found in this tea estate. Most of the workers are represented from indigenous and ethnic group with 20-40 age group. Similarly, a large number of tea workers are illiterate and landless as well as having low level of income. Key words: Women worker, Guranse tea estate, tea plantation, participation, income Introduction Tea is an important commercial cash crop in Nepal. Tea farming in Nepal has appeared as a significant agro-based industry that has been contributing vastly to the national economy in terms of generating employment opportunity as well as raising the revenue in the present days (Karki, 1981). Tea plantation was started in 1863 from Ilam, its expansion in the real sense, took place only after the establishment of Nepal Tea Development Corporation Board (NTDCB) in 1966 when first Rana Prime Minister Janga Bahadur Rana came in power. -

Problems in Bantawa Phonology and a Statistically Driven Approach to Vowels1 Rachel Vogel

Problems in Bantawa Phonology and a Statistically Driven Approach to Vowels1 Rachel Vogel A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Linguistics Swarthmore College December 2015 Abstract This thesis examines several aspects of the phonology of Bantawa, an endangered and fairly understudied Tibeto-Burman language of N epa!. I provide a brief review of the major literature on Bantawa to date and discuss two particular phonological controversies: one concerning the presence of retroflex consonants, and one concerning the vowel inventory, specifically whether there are six or seven vowel phonemes. I draw on data I recorded from a native speaker to address each of these issues. With regard to the latter, I also provide an in-depth acoustic analysis of my consultant's 477 vowels and consider several types of statistical models to help address the issue of the number of vowel contrasts. My main conclusions, based on the data from my consultant, are first, that there is evidence based on minimal pairs for a contrast between retroflex and alveolar stops, and second, that there is no clear evidence for a seven-vowel system in Bantawa. With regard to the latter point, additional avenues of research would still be needed to explore the possibility of allophonic variation and/or individual speaker differences. L Introduction There are over 120 languages spoken throughout Nepal, representing four different language families (Lewis et al. 2014; Ghimire 2013). Due to the lasting effects of a long history of social, political, and economic pressures, however, many of these languages are now endangered (Toba et al.