Ceramic, Meant As an Expression of Art, Is a Part of the Human Beings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Padua Municipal Archives from the 13 to the 20 Centuries

Padua Municipal Archives from the 13th to the 20th Centuries: A Case of a Record-keeping System in Italy GIORGETTA BONFIGLIO-DOSIO RÉSUMÉ L’auteure décrit dans cet article le système de gestion des documents de 1’administration municipale de Padoue entre le 13e et le 20e siècle, par la commune libre, la seigneurie des Carraresi, les fonctionnaires de la république de Venise, puis 1’administration locale avant et après 1’unification nationale (1861, mais 1866 pour Venise et Padoue). Elle analyse principalement la chancellerie médiévale et moderne, alors que les archives étaient conservées et gardées par des institutions chargées de 1’administration publique, puis le travail bureaucratique et historiographique exécuté aux 19e et 20e siècles. À cette époque, de nouvelles méthodes de gestion, adoptées par les états créés par Napoléon et s’appliquant aux archives courantes, ont également influencé la conservation des archives historiques. Cet article montre comment une ville italienne a conservé sa mémoire administrative et a créé une institution spécifique afin de préserver et d’étudier ses documents historiques. ABSTRACT This research describes the record-keeping systems of Padua’s municipal administration from the 13th to the 20th centuries, i.e., by free commune, Carraresis’ seigniory, public servants of the Republic of Venice, and local administration in the context of the State before and after the national unification (1861, but for Veneto and Padua 1866). The focus is on the analysis of the medieval and modern chancellery, while archives were preserved and kept by corporate bodies charged with public administration, and afterwards bureaucratic and historiographical work carried out in the 19th and the 20th centuries. -

The Business Organisation of the Bourbon Factories

The Business Organization of the Bourbon Factories: Mastercraftsmen, Crafts, and Families in the Capodimonte Porcelain Works and the Royal Factory at San Leucio Silvana Musella Guida Without exaggerating what was known as the “heroic age” of the reign of Charles of Bourbon of which José Joaquim de Montealegre was the undisputed doyen, and without considering the controversial developments of manufacturing in Campania, I should like to look again at manufacturing under the Bourbons and to offer a new point of view. Not only evaluating its development in terms of the products themselves, I will consider the company's organization and production strategies, points that are often overlooked, but which alone can account for any innovative capacity and the willingness of the new government to produce broader-ranging results.1 The two case studies presented here—the porcelain factory at Capodimonte (1740-1759) and the textile factory in San Leucio (1789-1860)—though from different time periods and promoted by different governments, should be considered sequentially precisely because of their ability to impose systemic innovations.2 The arrival of the new sovereign in the company of José Joaquin de Montealegre, led to an activism which would have a lasting effect.3 The former was au fait with economic policy strategy and the driving force of a great period of economic modernization, and his repercussions on the political, diplomatic and commercial levels provide 1 For Montealegre, cf. Raffaele Ajello, “La Parabola settecentesca,” in Il Settecento, edited by Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli (Naples, 1994), 7-79. For a synthesis on Bourbon factories, cf. Angela Carola Perrotti, “Le reali manifatture borboniche,” in Storia del Mezzogiorno (Naples, 1991), 649- 695. -

FINE EUROPEAN CERAMICS Including the Collezione Fiordalisi of Neapolitan Porcelain Thursday 7 December 2017

FINE EUROPEAN CERAMICS Including the Collezione Fiordalisi of Neapolitan porcelain Thursday 7 December 2017 SPECIALIST AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES EUROPEAN CERAMICS Sebastian Kuhn Nette Megens Sophie von der Goltz lot 44 FINE EUROPEAN CERAMICS Including the Collezione Fiordalisi of Neapolitan porcelain Thursday 7 December 2017 at 2pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES PHYSICAL CONDITION OF Sunday 3 December Nette Megens Monday to Friday 8.30am LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 11am - 5pm Head of Department to 6pm PLEASE NOTE THAT ANY Monday 4 December +44 (0) 20 7468 8348 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 REFERENCE IN THIS 9am - 4.30pm [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Tuesday 5 December Please see page 2 for bidder CONDITION OF ANY LOT IS FOR 9am - 4.30pm Sebastian Kuhn information including after-sale GENERAL GUIDANCE ONLY. Wednesday 6 December Department Director collection and shipment INTENDING BIDDERS MUST 9am - 4.30pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8384 SATISFY THEMSELVES AS TO Thursday 7 December [email protected] THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT by appointment AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 OF Sophie von der Goltz THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS SALE NUMBER Specialist CONTAINED AT THE END OF 24224 +44 (0) 20 7468 8349 THIS CATALOGUE. [email protected] CATALOGUE As a courtesy to intending Rome bidders, Bonhams will provide a £25.00 Emma Dalla Libera written indication of the physical Director condition of lots in this sale if a BIDS request is received up to 24 hours +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 +39 06 485900 before the auction starts. This +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax [email protected] written Indication is issued To bid via the internet please subject to Clause 3 of the Notice visit bonhams.com International Director European Ceramics & Glass to Bidders. -

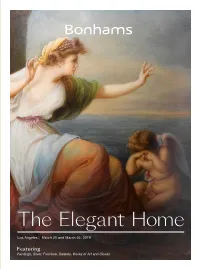

The Elegant Home

The Elegant Home The Home Elegant Ӏ Los Angeles Ӏ March 25 and March 26, 2019 25 and March March Bonhams The Elegant Home 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles CA 90046 Los Angeles | March 25 and March 26, 2019 25350 +1 (323) 850 7500 +1 (323) 850 6090 fax Featuring bonhams.com Paintings, Silver, Furniture, Carpets, Works of Art and Clocks AUCTIONEERS SINCE 1793 The Elegant Home Los Angeles SALE BIDS ILLUSTRATIONS REGISTRATION Monday March 25, 2019 at 10am +1 (323) 850 7500 Front cover: Lot 432 (detail) IMPORTANT NOTICE Tuesday March 26, 2019 at 10am +1 (323) 850 6090 fax Inside front cover: Lot 780 (detail) Please note that all customers, Day 1: Lot 350 (detail) irrespective of any previous activity VIEWINGS To bid via the internet please visit Day 2: Lot 512 with Bonhams, are required to Friday March 22, 12pm-5pm www.bonhams.com/25350 Inside back cover: Lot 118 complete the Bidder Registration Saturday March 23, 12pm-5pm Back cover: Lot 114 Form in advance of the sale. The Sunday March 24, 12pm-5pm Please note that bids must be form can be found at the back submitted no later than 4pm on of every catalogue and on our VENUE the day prior to the auction. New website at www.bonhams.com 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard bidders must also provide proof and should be returned by email or Los Angeles, California 90046 of identity and address when post to the specialist department bonhams.com submitting bids. or to the bids department at [email protected] SALE NUMBER Please contact client services with 25350 any bidding inquiries. -

Venetian Foreign Affairs from 1250 to 1381: the Wars with Genoa and Other External Developments

Venetian Foreign Affairs from 1250 to 1381: The Wars with Genoa and Other External Developments By Mark R. Filip for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History College of Liberal Arts and Sciences University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 1988 Table of Contents Major Topics page Introduction 1 The First and Second Genoese Wars 2 Renewed Hostilities at Ferrara 16 Tiepolo's Attempt at Revolution 22 A New Era of Commercial Growth 25 Government in Territories of the Republic 35 The Black Death and Third ' < 'ioese War 38 Portolungo 55 A Second Attempt at Rcvoiut.on 58 Doge Gradenigo and Peace with Genoa 64 Problems in Hungary and Crete 67 The Beginning of the Contarini Dogcship 77 Emperor Paleologus and the War of Chioggia 87 The Battle of Pola 94 Venetian Defensive Successes 103 Zeno and the Venetian Victory 105 Conclusion 109 Endnotes 113 Annotated Bibliography 121 1 Introduction In the years preceding the War of Chioggia, Venetian foreign affairs were dominated by conflicts with Genoa. Throughout the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the two powers often clashed in open hostilities. This antagonism between the cities lasted for ten generations, and has been compared to the earlier rivalry between Rome and Carthage. Like the struggle between the two ancient powers, the Venetian/Gcnoan hatred stemmed from their competitive relationship in maritime trade. Unlike land-based rivals, sea powers cannot be separated by any natural boundary or agree to observe any territorial spheres of influence. Trade with the Levant, a source of great wealth and prosperity for each of the cities, required Venice and Genoa to come into repeated conflict in ports such as Chios, Lajazzo, Acre, and Tyre. -

Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929) October 2019 Sculptor of the Neapolitan Soul from 15 October 2019 to 26 January 2020

PRESS KIT Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929) October 2019 Sculptor of the Neapolitan soul from 15 October 2019 to 26 January 2020 Tuesday to Sunday 10am to 6pm INFORMATIONS Late opening Friday until 9pm www.petitpalais.paris.fr . Museo e Certosa di San Martino, Photo STUDIO SPERANZA STUDIO Photo Head of a young boy Naples. Fototeca del polo museale della campaniaNaples. Fototeca Vincenzo Gemito, PRESS OFFICER : Mathilde Beaujard [email protected] / + 33 1 53 43 40 14 Exposition organised in With the support of : collaboration with : Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929), Sculptor of the Neapolitan soul- from 15 October 2019 to 26 January 2020 SOMMAIRE Press release p. 3 Guide to the exhibition p. 5 The Exhibition catalogue p. 11 The Museum and Royal Park of Capodimonte p. 12 Paris Musées, a network of Paris museums p. 19 About the Petit Palais p. 20 Practical information p. 21 2 Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929), Sculptor of the Neapolitan soul- from 15 October 2019 to 26 January 2020 PRESS RELEASE At the opening of our Neapolitan season, the Petit Pa- lais is pleased to present work by sculptor Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929) that has never been seen in France. Gemito started life abandoned on the steps of an or- phanage in Naples. He grew up to become one of the greatest sculptors of his era, celebrated in his home- town and later in the rest of Italy and Europe. At the age of twenty-five, he was a sensation at the Salon in Paris and, the following year, at the 1878 Universal Ex- position. -

Antiques & Collectables

An online live auction Antiques & Collectables Wednesday 9th September at 11.00am Wednesday CATHERINE SOUTHON auctioneers & valuers ltd ANTIQUES & COLLECTABLES - September 2020 Antiques & Collectables Wednesday 9th September at 11.00am VIEWING By strict appointment on Monday 7th from 2pm-5pm Tuesday 8th from 9am-6pm Morning of the sale until 11am Please telephone 07808 737694 or 0208 468 1010 (not week of auction) Please note that in line with Government restrictions, this is not a public auction. Bidding will take place online, by telephone or by leaving absentee bids in advance of the auction PLEASE NOTE THAT WE WILL BE MOVING OFFICES FROM 1ST SEPTEMBER 2020 TO: Airivo Chislehurst 1 Bromley Lane Chislehurst Kent BR7 6LH HOWEVER THE AUCTION AND VIEWING WILL TAKE PLACE AT FARLEIGH GOLF CLUB AS USUAL Welcome to Catherine Southon Auctioneers & Valuers Director: Catherine Southon MA Specialists: Tom Blest Prudence Hopkins Sale Administrator: Nicola Minney Auction Enquiries and Information: 0208 313 3655 (Before 1st September) 0208 468 1010 (After 1st September) 07596 332978 07808 737694 Email: [email protected] IMPORTANT NOTICES Please note that the condition of items are not noted in the catalogue. Condition reports can be viewed on www.thesaleroom.com. All payments should be made by bank transfer, debit card or through www.thesaleroom.com. Please note that we are no longer taking credit cards as payment. COLLECTIONS Items must be collected by strict appointment from Farleigh Golf Club by 4:30pm on Friday 11th September. After this time they will be taken to our new office at Airivo Chislehurst 1 Bromley Lane Chislehurst Kent BR7 6LH. -

FINE EUROPEAN CERAMICS Wednesday 14 June 2017

FINE EUROPEAN CERAMICS Wednesday 14 June 2017 SPECIALIST AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES EUROPEAN CERAMICS Sebastian Kuhn Nette Megens Sophie von der Goltz FINE EUROPEAN CERAMICS Wednesday 14 June 2017 at 2pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES PHYSICAL CONDITION OF Sunday 11 June Nette Megens Monday to Friday 8.30am LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 11am - 3pm Head of Department to 6pm PLEASE NOTE THAT ANY Monday 12 June +44 (0) 20 7468 8348 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 REFERENCE IN THIS 9am - 4.30pm [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Tuesday 13 June Please see page 2 for bidder CONDITION OF ANY LOT IS FOR 9am - 4.30pm Sebastian Kuhn information including after-sale GENERAL GUIDANCE ONLY. +44 (0) 20 7468 8384 collection and shipment INTENDING BIDDERS MUST SALE NUMBER [email protected] SATISFY THEMSELVES AS TO 24223 THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sophie von der Goltz AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 OF CATALOGUE +44 (0) 20 7468 8349 THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF £25.00 THIS CATALOGUE. International Director BIDS As a courtesy to intending +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 European Ceramics & Glass bidders, Bonhams will provide a +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax John Sandon written indication of the physical To bid via the internet please +44 (0) 20 7468 8244 condition of lots in this sale if a visit bonhams.com [email protected] request is received up to 24 hours before the auction starts. This Please note that bids should be written Indication is issued submitted no later than 4pm on subject to Clause 3 of the Notice the day prior to the sale. -

Il Palazzo Comunale Di Udine Da Nicolò Lionello a Raimondo D'aronco

Il Palazzo comunale di Udine Il Palazzo comunale di Udine da Nicolò Lionello a Raimondo D’Aronco da Nicolò Lionello a Raimondo D’Aronco Quest'opera è rilasciata con licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione 4.0 Internazionale. Per leggere una copia della licenza visita il sito web http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ o spedisci una lettera a Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Il Palazzo comunale di Udine da Nicolò Lionello a Raimondo D’Aronco Amministrazione comunale di Udine Fotografie: Archivio Fantoni Gemona, Giuseppe Bergamini, Renato Bergamini, Paolo Brisighelli, Luigi Fiorini, Claudio Marcon, Udine Civici Musei © Per i testi: Diana Barillari, Giuseppe Bergamini Si ringrazia per la cortese collaborazione: Paolo Brisighelli, Gabriella Bucco, Liliana Cargnelutti, Alessandra Fantoni, Vania Gransinigh, Loris Milocco, Dania Nobile, Valentina Zancan Progetto grafico e impaginazione: Rubbettino print Stampa: Rubbettino print - Viale Rosario Rubbettino, 8 - 88049 Soveria Mannelli (CZ) ISBN: 9788895752297 Indice 7 Introduzione 9 Prefazione GIUSEPPE BERGAMINI 11 La Loggia del Comune DIANA BARILLARI 51 La fabbrica del Palazzo Comunale di Raimondo D’Aronco, storia tecnica utopia 114 Cronologia del nuovo Palazzo Comunale 118 Fonti archivistiche 118 Bibliografia Introduzione Finalmente Palazzo D’Aronco e la sua storia tornano accessibili agli udinesi. Il Comune è per definizione la casa dei cittadini ed è anche per questo motivo, oltre che per l’indiscusso valore artistico del Palazzo, che la decisione di riaprirlo e farlo conoscere ai tanti turisti, ma anche agli stessi udinesi, ha un significato importante e si inserisce a pieno titolo nell’idea di una città aperta, consapevole della propria storia e orgogliosa dei propri tesori. -

The States of Italy History of Verona Am

www.cristoraul.org THE STATES OF ITALY HISTORY OF VERONA A. M. ALLEN 1 www.cristoraul.org PREFACE THERE is no need to explain the origin of this attempt to write the history of Verona, the inherent fascination of the subject speaks for itself. But I cannot let this volume appear without expressing my sincere thanks to all who have assisted me during its preparation. First and foremost I desire to thank the cavaliere Gaetano da Re, of the Biblioteca Comunale at Verona, who, during my two visits to Verona, in 1904 and 1906, placed at my disposal the treasures both of the library and of his learning with the most generous kindness, and since then has settled more than one difficult point. From the other officials of this library, and those of the other libraries I visited, the Biblioteca Capitolare at Verona, the Biblioteca Marciana and the Archivio di Stato (in the Frari) at Venice, and the Archivio Gonzaga at Mantua, I met with the same unfailing and courteous assistance. Among modern works I have found Count Carlo Cipolla’s writings on Verona and his scholarly edition of the early Veronese chroniclers invaluable, while J. M. Gittermann’s Ezzelino III. da Romano, E. Salzer’s Ueber die Anfange der Signorie in Oberitalien, and H. Spangenberg’s Cangrande I are all of the first importance for various periods of Veronese history. My thanks are also due to Miss Croom-Brown, who constructed the three maps, the result of much careful research, and to my cousin, Mr. Alfred Jukes Allen, who read the proofs with minute accuracy. -

Oggetto: Mura Porta Legnago E Porta Vicenza RUP: Arch. Rita Berton

Comune: Montagnana (Padova) Oggetto: Mura Porta Legnago e Porta Vicenza RUP: Arch. Rita Berton – Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio per l’area metropolitana di Venezia e le province di Belluno, Padova e Treviso Progettista: Arch. Edi Pezzetta – Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio per l’area metropolitana di Venezia e le province di Belluno, Padova e Treviso Proprietà: demaniale e comunale Finanziamento: Programma Triennale L. n. 190/2014 (art. 1, c.9 e 10) Totale finanziamento: 900.000,00 euro Stazione appaltante: Segretariato regionale per il Veneto Avanzamento al 01/02/2018: progetto trasmesso a Centrale di Committenza Invitalia in data 27/12/2016 – Procedura di gara in istruttoria. Descrizione. La cinta muraria attuale di Montagnana è il frutto di un ampliamento della fortificazione ad opera dei Carraresi, iniziato a partire dal 1340. Il perimetro difensivo si sviluppa entro una serie cadenzata di ventiquattro torricini pentagonali, collegati tra loro dal relativo cammino di ronda. La Porta occidentale, in direzione della città di Legnago, detta “Rocca degli Alberi”, risale al medesimo periodo di riordino difensivo operato dai Carraresi. Porta Vicenza, invece, o “Porta Nuova”, è l’esito della trasformazione di una delle torri in porta di accesso alla città. Munita di ponte e antemurale difensivo fungeva da collegamento tra i borghi esterni e il sistema difensivo interno. Lo stato di conservazione di Porta Legnago presenta elementi di criticità nel sistema di merlature sommitale, anche se i pesanti interventi strutturali realizzati nel mastio, attorno agli anni Sessanta, ne hanno assicurato l’efficienza statica. In generale tutta la struttura presenta vari livelli di degrado causato sia dagli agenti atmosferici, sia da azione meccanica dovuta agli urti del transito veicolare, pur regolamentato nell’accesso alla Porta. -

Insider Journeys Letterhead

The Beauty of Veneto! Self-Drive Tour [email protected] https://flashsales.travel Australia – Spain – Thailand – United Kingdom – United States of America – Vietnam IJFSPC-ALLCY-144 Your DEAL Includes Your Country Italy Your Destination Venice - Padua Your Deal The Beauty of Veneto – Self-Drive Tour Hotel Category Venice Padua Deal Validity 01 May 2021 – 31 October 2021 Non Bookable Dates 01 September 2021 – 11 September 2021 Travel Dates Daily Deal Length 8 Days and 7 Nights 3 nights Hotel Giardinetto in Comfort Lagoon View 4 nights Hotel Majestic Toscanelli or similar in Padua Daily breakfast for 2 people Public transport in/out in Venice Deal Inclusions Assistance on arrival and departure Tour: Venice 1600 years of history Car rental for 5 days Suggested self-guided itineraries per day Your Bonus 1 Bottle of Wine upon arrival Venice Hotel City Tax €2,80 per person, per day Padua Hotel City Tax €2,80 per person, per day Deal Exclusions Insurance and Fuel for Rental car Entrance Fees More Infos about exclusions & cancellation terms please scroll Additional Notes down [email protected] https://flashsales.travel Australia – Spain – Thailand – United Kingdom – United States of America – Vietnam Hotel Description Hotel Giardinetto The Giardinetto is a cozy small 3* hotel conveniently located in Lido island, just 12’ of vaporetto from St. Mark’s square (the journey itself is a tour!). You will be staying at one of the hotels 4 comfort double rooms with lagoon view. Each room is equipped with a kettle, tea and coffee. Iron & board for your last need, bottle of drinkable water with glasses, hairdryer, a/c, free Wi-Fi, tv set.