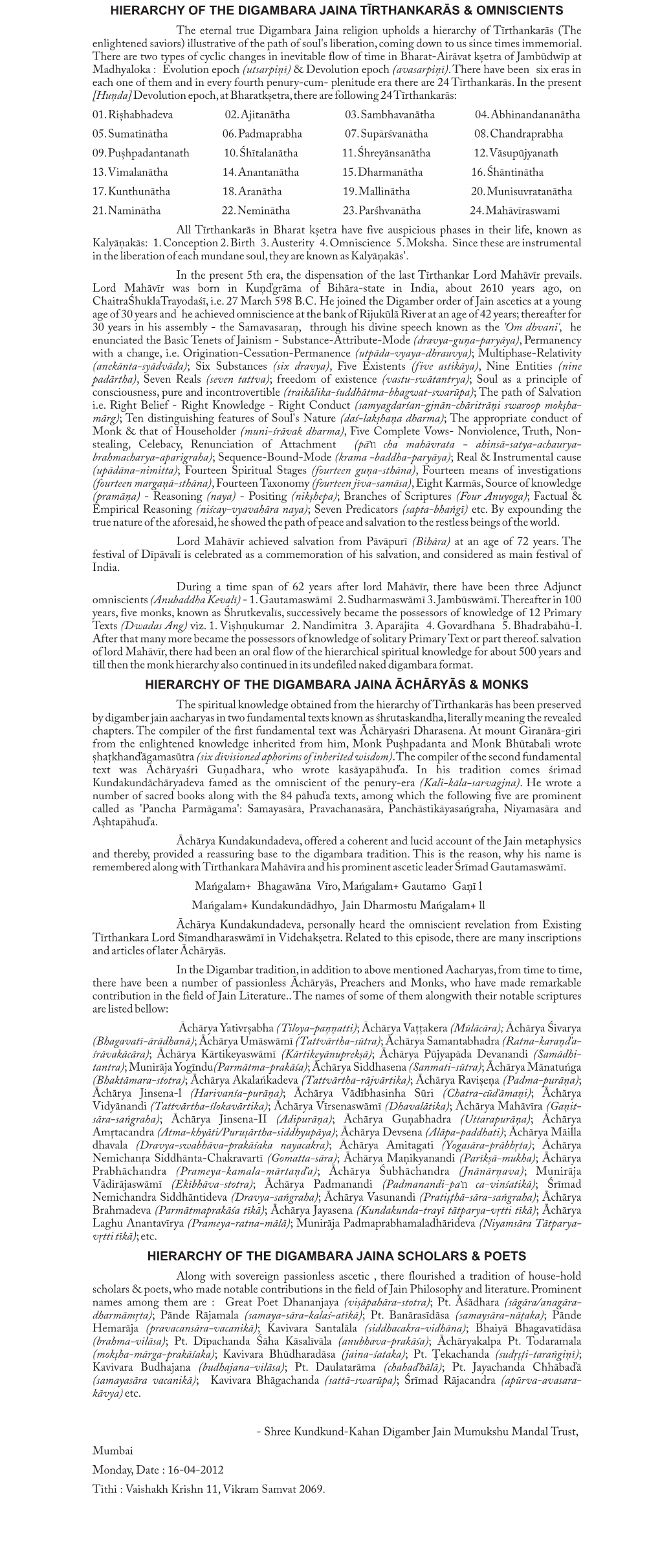

Hierarchy of the Digambara Jaina Tirthankaras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ratnakarandaka-F-With Cover

Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni VIJAY K. JAIN Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Depiction of the Holy Feet of the twenty-fourth Tīrthaôkara, Lord Mahāvīra, at the sacred hills of Shri Sammed Shikharji, the holiest of Jaina pilgrimages, situated in Jharkhand, India. Pic by Vijay K. Jain (2016) Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct Vijay K. Jain Non-Copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original and that a mention is made of the source. ISBN 81-903639-9-9 Rs. 500/- Published, in the year 2016, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India www.vikalpprinters.com E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun (iv) eaxy vk'khokZn & ijeiwT; fl¼kUrpØorhZ 'osrfiPNkpk;Z Jh fo|kuUn th eqfujkt milxsZ nq£Hk{ks tjfl #tk;ka p fu%izfrdkjs A /ekZ; ruqfoekspuekgq% lYys[kukek;kZ% AA 122 AA & vkpk;Z leUrHkæ] jRudj.MdJkodkpkj vFkZ & tc dksbZ fu"izfrdkj milxZ] -

An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide

AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 1 2Prakrit Bharati academy,An Ahimsa Crisis: Jai YouP Decideur Prakrit Bharati Pushpa - 356 AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 3 Publisher: * D.R. Mehta Founder & Chief Patron Prakrit Bharati Academy, 13-A, Main Malviya Nagar, Jaipur - 302017 Phone: 0141 - 2524827, 2520230 E-mail : [email protected] * First Edition 2016 * ISBN No. 978-93-81571-62-0 * © Author * Price : 700/- 10 $ * Computerisation: Prakrit Bharati Academy, Jaipur * Printed at: Sankhla Printers Vinayak Shikhar Shivbadi Road, Bikaner 334003 An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 4by Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide Contents Dedication 11 Publishers Note 12 Preface 14 Acknowledgement 18 About the Author 19 Apologies 22 I am honored 23 Foreword by Glenn D. Paige 24 Foreword by Gary Francione 26 Foreword by Philip Clayton 37 Meanings of Some Hindi & Prakrit Words Used Here 42 Why this book? 45 An overview of ahimsa 54 Jainism: a living tradition 55 The connection between ahimsa and Jainism 58 What differentiates a Jain from a non-Jain? 60 Four stages of karmas 62 History of ahimsa 69 The basis of ahimsa in Jainism 73 The two types of ahimsa 76 The three ways to commit himsa 77 The classifications of himsa 80 The intensity, degrees, and level of inflow of karmas due 82 to himsa The broad landscape of himsa 86 The minimum Jain code of conduct 90 Traits of an ahimsak 90 The net benefits of observing ahimsa 91 Who am I? 91 Jain scriptures on ahimsa 91 Jain prayers and thoughts 93 -

The Decline of Buddhism in India

The Decline of Buddhism in India It is almost impossible to provide a continuous account of the near disappearance of Buddhism from the plains of India. This is primarily so because of the dearth of archaeological material and the stunning silence of the indigenous literature on this subject. Interestingly, the subject itself has remained one of the most neglected topics in the history of India. In this book apart from the history of the decline of Buddhism in India, various issues relating to this decline have been critically examined. Following this methodology, an attempt has been made at a region-wise survey of the decline in Sind, Kashmir, northwestern India, central India, the Deccan, western India, Bengal, Orissa, and Assam, followed by a detailed analysis of the different hypotheses that propose to explain this decline. This is followed by author’s proposed model of decline of Buddhism in India. K.T.S. Sarao is currently Professor and Head of the Department of Buddhist Studies at the University of Delhi. He holds doctoral degrees from the universities of Delhi and Cambridge and an honorary doctorate from the P.S.R. Buddhist University, Phnom Penh. The Decline of Buddhism in India A Fresh Perspective K.T.S. Sarao Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-215-1241-1 First published 2012 © 2012, Sarao, K.T.S. All rights reserved including those of translation into other languages. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Life of Mahavira As Described in the Jai N a Gran Thas Is Imbu Ed with Myths Which

T o be h a d of 1 T HE MA A ( ) N GER , T HE mu Gu ms J , A llahaba d . Lives of greatmen all remin d u s We can m our v s su m ake li e bli e , A nd n v hi n u s , departi g , lea e be d n n m Footpri ts o the sands of ti e . NGF LL W LO E O . mm zm fitm m m ! W ‘ i fi ’ mz m n C NT E O NT S. P re face Introd uction ntrod uctor remar s and th i I y k , e h storicity of M ahavira Sources of information mt o o ica stories , y h l g l — — Family relations birth — — C hild hood e d ucation marriage and posterity — — Re nou ncing the world Distribution of wealth Sanyas — — ce re mony Ke sh alochana Re solution Seve re pen ance for twe lve years His trave ls an d pre achings for thirty ye ars Attai n me nt of Nirvan a His disciples and early followers — H is ch aracte r teachings Approximate d ate of His Nirvana Appendix A PREF CE . r HE primary con dition for th e formation of a ” Nation is Pride in a common Past . Dr . Arn old h as rightly asked How can th e presen t fru th e u u h v ms h yield it , or f t re a e pro i e , except t eir ” roots be fixed in th e past ? Smiles lays mu ch ’ s ss on h s n wh n h e s s in his h a tre t i poi t , e ay C racter, “ a ns l n v u ls v s n h an d N tio , ike i di id a , deri e tre gt su pport from the feelin g th at they belon g to an u s u s h h th e h s of h ill trio race , t at t ey are eir t eir n ss an d u h u s of h great e , o g t to be perpet ator t eir is of mm n u s im an h n glory . -

Book Review - the Jains

Book Review - The Jains The Jains, by Paul Dundas, is the leading general introduction to Jainism and part of the Library of Religious Beliefs and Practices series by Routledge Press. The author, Paul Dundas, is a Sanskrit scholar in the School of Asian Studies at the University of Edinburgh. He is probably the foremost Western scholar on Jainism, and also lectures on Buddhism, Prakrit, and Indian cultural history. As such, Dundas is well qualified to pen this book. Summary Dundas begins with the Fordmakers, the twenty-four founders of the Jain religion from Rishabhanatha in prehistory to Mahavira (599-527 BC). Jainism adopted many of the Hindu beliefs, including reincarnation and the concept of release from the cycle of rebirth (moksha). It resulted in part from a reaction against violence, such as Vedic animal sacrifices in Hinduism, and came to maturity at the same time as Buddhism. Asceticism, denying desires and suppressing senses are major themes of Mahavira’s teaching. He emphasized the Three Jewels of Jainism; right faith, right knowledge and right practice. The two major sects of Jainism are the Svetambaras and the Digambaras. Monks and nuns from the former wear white robes, predominate in the north of India, and form the largest sect of Jains. Digambara monks go naked, while the nuns wear robes, and predominate in the warmer south of India. The sects have no large doctrinal differences, although Svetambaras believe that women can achieve deliverance (moksha) while Digambaras believe that deliverance from the cycles of rebirth is only available to men. A woman must be reborn as a man to achieve moksha. -

Nonviolence in the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist Traditions Dr

1 Nonviolence in the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist traditions Dr. Vincent Sekhar, SJ Arrupe Illam Arul Anandar College Karumathur – 625514 Madurai Dt. INDIA E-mail: [email protected] Introduction: Religion is a human institution that makes sense to human life and society as it is situated in a specific human context. It operates from ultimate perspectives, in terms of meaning and goal of life. Religion does not merely provide a set of beliefs, but offers at the level of behaviour certain principles by which the believing community seeks to reach the proposed goals and ideals. One of the tasks of religion is to orient life and the common good of humanity, etc. In history, religion and society have shaped each other. Society with its cultural and other changes do affect the external structure of any religion. And accordingly, there might be adaptations, even renewals. For instance, religions like Buddhism and Christianity had adapted local cultural and traditional elements into their religious rituals and practices. But the basic outlook of Buddhism or Christianity has not changed. Their central figures, tenets and adherence to their precepts, etc. have by and large remained the same down the history. There is a basic ethos in the religious traditions of India, in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism. Buddhism may not believe in a permanent entity called the Soul (Atman), but it believes in the Act (karma), the prime cause for the wells or the ills of this world and of human beings. 1 Indian religions uphold the sanctity of life in all its forms and urge its protection. -

On Corresponding Sanskrit Words for the Prakrit Term Posaha: with Special Reference to Śrāvakācāra Texts

International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) Vol. 13, No. 2 (2017) 1-17 ON CORRESPONDING SANSKRIT WORDS FOR THE PRAKRIT TERM POSAHA: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO ŚRĀVAKĀCĀRA TEXTS Kazuyoshi Hotta 1. Introduction In Brahmanism, the upavasathá purification rite has been practiced on the day prior to the performance of a Vedic ritual. We can find descriptions of this purification rite in Brahmanical texts, such as ŚBr 1.1.1.7, which states as follows. For assuredly, (he argued,) the gods see through the mind of man; they know that, when he enters on this vow, he means to sacrifice to them the next morning. Therefore all the gods betake themselves to his house, and abide by (him or the fires, upa-vas) in his house; whence this (day) is called upa-vasatha (Tr. Eggeling 1882: 4f.).1 This rite was then incorporated into Jainism and Buddhism in different ways, where it is known under names such as posaha or uposatha in Prakrit and Pāli. Buddhism adopted and developed the rite mainly as a ritual for mendicants. Many descriptions of this rite can be found in Buddhist vinaya texts. Furthermore, this rite is practiced until today throughout Buddhist Asia. On the other hand, Jainism has employed the rite mainly as a practice for the laity. Therefore, descriptions of Jain posaha are found in the group of texts called Śrāvakācāra, which contain the code of conduct for the laity. There are many forms of Śrāvakācāra texts. Some are independent texts, while others form part of larger works. Many of them consist mainly of the twelve vrata (restraints) and eleven pratimā (stages of renunciation) that should be observed by * This paper is an expanded version of Hotta 2014 and the contents of a paper delivered at the 19th Jaina Studies Workshop, “Jainism and Buddhism” (18 March 2017, SOAS). -

JAINISM Early History

111111xxx00010.1177/1111111111111111 Copyright © 2012 SAGE Publications. Not for sale, reproduction, or distribution. J Early History JAINISM The origins of the doctrine of the Jinas are obscure. Jainism (Jinism), one of the oldest surviving reli- According to tradition, the religion has no founder. gious traditions of the world, with a focus on It is taught by 24 omniscient prophets, in every asceticism and salvation for the few, was confined half-cycle of the eternal wheel of time. Around the to the Indian subcontinent until the 19th century. fourth century BCE, according to modern research, It now projects itself globally as a solution to the last prophet of our epoch in world his- world problems for all. The main offering to mod- tory, Prince Vardhamāna—known by his epithets ern global society is a refashioned form of the Jain mahāvīra (“great hero”), tīrthaṅkāra (“builder of ethics of nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and nonpossession a ford” [across the ocean of suffering]), or jina (aparigraha) promoted by a philosophy of non- (spiritual “victor” [over attachment and karmic one-sidedness (anekāntavāda). bondage])—renounced the world, gained enlight- The recent transformation of Jainism from an enment (kevala-jñāna), and henceforth propagated ideology of world renunciation into an ideology a universal doctrine of individual salvation (mokṣa) for world transformation is not unprecedented. It of the soul (ātman or jīva) from the karmic cycles belongs to the global movement of religious mod- of rebirth and redeath (saṃsāra). In contrast ernism, a 19th-century theological response to the to the dominant sacrificial practices of Vedic ideas of the European Enlightenment, which West- Brahmanism, his method of salvation was based on ernized elites in South Asia embraced under the the practice of nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and asceticism influence of colonialism, global industrial capital- (tapas). -

Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

JAIN VALUES, WORSHIP AND THE TIRTHANKARA IMAGE B.A., University of Washington, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard / THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1980 (c)Roy L. Leavitt In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date 14 October 1980 The main purpose of the thesis is to examine Jain worship and the role of the Jains1 Tirthankara images in worship. The thesis argues that the worshipper emulates the Tirthankara image which embodies Jain values and that these values define and, in part, dictate proper behavior. In becoming like the image, the worshipper's actions ex• press the common concerns of the Jains and follow a pattern that is prized because it is believed to be especially Jain. The basic orientation or line of thought is that culture is a system of symbols. These symbols are implicit agreements among the community's members, agreements which entail values and which permit the Jains to meaningfully interpret their experiences and guide their actions. -

Bio Diversity in Nature – in View of Prakrit Text and Modern Biology (A Critical Analysis)

Bio diversity in nature – In view of Prakrit text and Modern Biology (A critical analysis) Prof (Dr) S. L. Godawat Former Dean, Rajasthan College of Agriculture Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture & Technology Udaipur-313001 +91414850711 [email protected] Biodiversity is the abbreviated word for ― biological diversity (bio-life or living organisms, diversity-variation). Biodiversity is the total variety of life on our planet, the total number of races, varieties and species; the sum total of various types of microbes, plants and animals. In this article an attempt has been made to understand the cause of this variation in view of prakrit text/ Jainism and modern biology. According to Kund kund Deva in Pravachansar,Nama karm which determines the entire variability exists in four realms (gatiyan) viz; human beings(manushya), sub human beings (tiriyanch), celestials (deva) and hellish (narki)which are not real feature of the soul. क륍म णामसमव啍खं सभावमध अꥍऩनो सहावेण l .® अभभभयंू णरं तिररयं रइयं वा सरु ं कु णदिl ll 117 ll प्रवचनसार Ç.k Ùkk णरणारयतिररयसरु ा जीवा खऱ ु णामकक륍म 핍व l Ç.k णदह िे ऱ녍धसहावा ऩररणममाणासक륍मा ll 118 ll प्रवचनसार Swamikarttikey in Karttikeyanupreksha - The power of Nama karma hides the real feature of soul (infinite knowledge, infinite vision , infinite pleasure, infinite power) and give rise to different realms.. का वव अउ핍वा दिसदि ऩु嵍गऱ ि핍वस एररसी स配िी l केवऱ - णाण सहावो ववणाभसिो जाड जीवस ll 211 ll कतिकि े यानुप्रेऺा Devsenacharya in aalappaddhti- Mundana souls (worldly souls) exhibits four kinds of vibhav vayanjan paryaya (modifications/forms) - human beings (manushya), sub human beings (tiriyanch), celestials (deva) and hellish (narki) in details 84 lakh yoni. -

Jain Philosophy and Practice I 1

PANCHA PARAMESTHI Chapter 01 - Pancha Paramesthi Namo Arihantänam: I bow down to Arihanta, Namo Siddhänam: I bow down to Siddha, Namo Äyariyänam: I bow down to Ächärya, Namo Uvajjhäyänam: I bow down to Upädhyäy, Namo Loe Savva-Sähunam: I bow down to Sädhu and Sädhvi. Eso Pancha Namokkäro: These five fold reverence (bowings downs), Savva-Pävappanäsano: Destroy all the sins, Manglänancha Savvesim: Amongst all that is auspicious, Padhamam Havai Mangalam: This Navakär Mantra is the foremost. The Navakär Mantra is the most important mantra in Jainism and can be recited at any time. While reciting the Navakär Mantra, we bow down to Arihanta (souls who have reached the state of non-attachment towards worldly matters), Siddhas (liberated souls), Ächäryas (heads of Sädhus and Sädhvis), Upädhyäys (those who teach scriptures and Jain principles to the followers), and all (Sädhus and Sädhvis (monks and nuns, who have voluntarily given up social, economical and family relationships). Together, they are called Pancha Paramesthi (The five supreme spiritual people). In this Mantra we worship their virtues rather than worshipping any one particular entity; therefore, the Mantra is not named after Lord Mahävir, Lord Pärshva- Näth or Ädi-Näth, etc. When we recite Navakär Mantra, it also reminds us that, we need to be like them. This mantra is also called Namaskär or Namokär Mantra because in this Mantra we offer Namaskär (bowing down) to these five supreme group beings. Recitation of the Navakär Mantra creates positive vibrations around us, and repels negative ones. The Navakär Mantra contains the foremost message of Jainism. The message is very clear. -

1 Mapping Monastic Geographicity Or Appeasing Ghosts of Monastic Subjects Indrani Chatterjee

1 Mapping Monastic Geographicity Or Appeasing Ghosts of Monastic Subjects Indrani Chatterjee Rarely do the same apparitions inhabit the work of modern theorists of subjectivity, politics, ethnicity, the Sanskrit cosmopolis and medieval architecture at once. However, the South Asianist historian who ponders the work of Charles Taylor, Partha Chatterjee, James Scott and Sheldon Pollock cannot help notice the apparitions of monastic subjects within each. Tamara Sears has gestured at the same apparitions by pointing to the neglected study of monasteries (mathas) associated with Saiva temples.1 She finds the omission intriguing on two counts. First, these monasteries were built for and by significant teachers (gurus) who were identified as repositories of vast ritual, medical and spiritual knowledge, guides to their practice and over time, themselves manifestations of divinity and vehicles of human liberation from the bondage of life and suffering. Second, these monasteries were not studied even though some of these had existed into the early twentieth century. Sears implies that two processes have occurred simultaneously. Both are epistemological. One has resulted in a continuity of colonial- postcolonial politics of recognition. The identification of a site as ‘religious’ rested on the identification of a building as a temple or a mosque. Residential sites inhabited by religious figures did not qualify for preservation. The second is the foreshortening of scholarly horizons by disappeared buildings. Modern scholars, this suggests, can only study entities and relationships contemporaneous with them and perceptible to the senses, omitting those that evade such perception or have disappeared long ago. This is not as disheartening as one might fear.